In response to my post of August 9, “Underground,” archivist-historian and Orphans veteran Paul Spehr commented about early advocacy for underground storage for film preservation. He began working in the Library of Congress Motion Picture Section in 1958, retiring as assistant chief in 1993.

In the early 1960s the LoC was presented with a collection of 35mm negatives of films shot by Herford Cowling for Burton Holmes for showing at the 1933 Chicago World Fair. Cowling had been a very early consultant on standards for storage of motion picture film — going back to the 1920s and contributing to the establishment of the National Archives film archive in 1934-36. He was a very early advocate of stable cold temperature and RH [relative humidity].

One of his very early recommendations was use of caves when proper vault space wasn’t available. He had access to a cave near Luray Caverns, Virginia and had kept his films there — and they were in the best condition I ever experienced.

— Paul Spehr, Orphan Film Symposium Facebook group, Aug. 10, 2019.

As it happens, Luray Caverns is only 40 miles from the bunkers that now house the Library of Congress National Audio Visual Conservation Center’s film vaults in Culpeper, Virginia.

I was ignorant of Cowling’s work, but an initial search of databases for his eminently searchable name reveals a remarkable career, both as a filmmaker who traveled the world and a preservation advocate who made a genuine contribution to film archiving. He shot hundreds of thousands of feet of film in the first four decades of his career. Some of it is archived, due to his work for government agencies. Much of it is scattered in private collections and archives. Some is identifiable (but not credited) in compilation films by others. Much of it does not appear to survive.

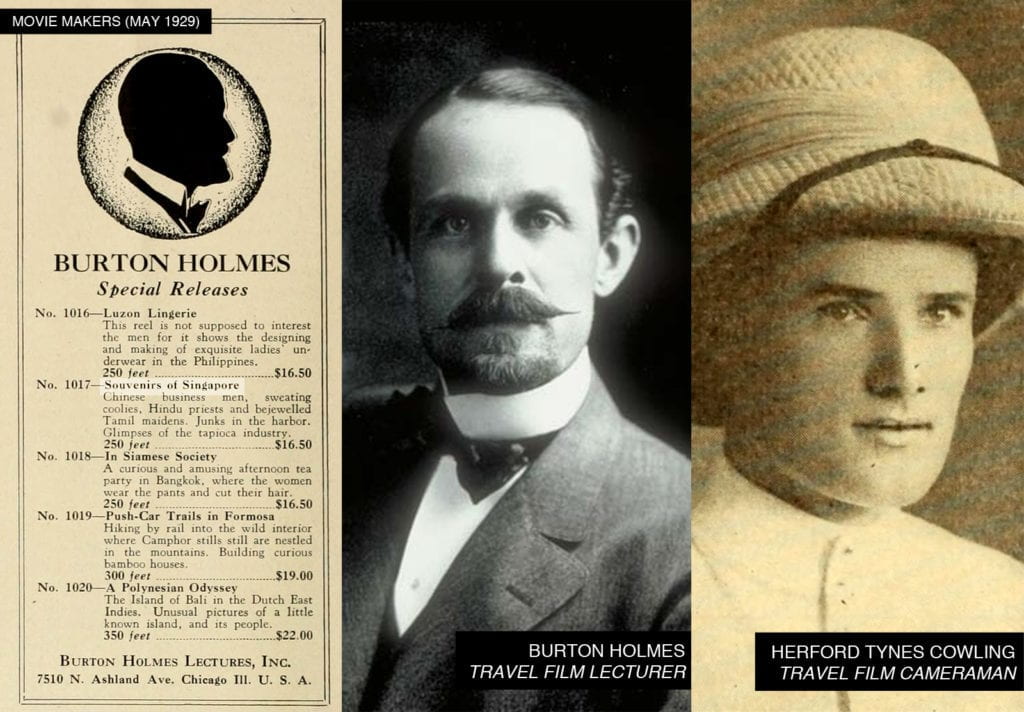

Herford Tynes Cowling (1890-1980) was born in (and died in) Virginia, traveling the world as a photographer, cinematographer, film director, producer — and freemason! The book 10,000 Freemasons (Denslow, 1957) offers this bio: “Was chief photographer for U.S. Reclamation Service in 1906-1916 traveling extensively in U.S., Canada and Mexico. Headed cinematographic expedition to Formosa, Philippines, Indo-China, Siam, Tasmania, and South Sea islands, producing semi-educational [sic] movies in 1917. Was chief cinematographer for Paramount (Burton Holmes Travel Films). He has also been technical advisor for Eastman Kodak, official photographer of Century of Progress in Chicago, technical director for U.S. National Archives, Washington, chief of photographic services, Dept. of Labor. In 1922 was on expedition to East Africa, Uganda, Congo and The Sudan. Made movies in Tibet and was China war correspondent in 1924.”

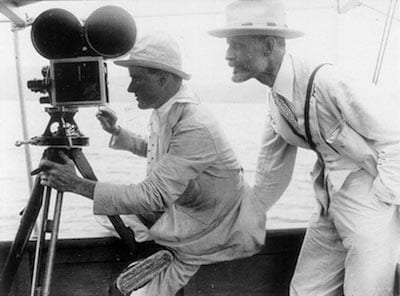

—- Cowling at the camera, with Holmes in Japan, 1917. © Burton Holmes Historical Collection.

—- Cowling at the camera, with Holmes in Japan, 1917. © Burton Holmes Historical Collection.

At the 2001 Orphan Film Symposium, Buckey Grimm‘s talk “Early Preservation Initiatives” included these additional details. In 1932, the Society of Motion Picture Engineers’ first Committee on the Preservation of Film included Cowling, Carl Louis Gregory, and Terry Ramsaye. In 1934, the new Motion Picture Division of the U.S. National Archives hired Cowling. His “expertise was well documented,” Grimm reported. “His career began in 1910 as chief photographer for the U.S. Interior Department. In 1916, he made a series of travelogues called See America First for Metro Pictures, then was Technical Director for Eastman Teaching Films. He was a recognized expert in storage and handling of nitrate film.” [Later published as Grimm, “A History of Early Nitrate Testing and Storage, 1910-1945,” The Moving Image 1.2 (2001).]

After World War II, Colonel Cowling remained in the U.S. Army Air Force, working at the film lab, as “chief of the Division of Photography, Technical Intelligence of Air Material Command at Wright Field, Ohio,” no less. (Motion Picture Herald, Nov. 9, 1946.) Twenty years after he gave Spehr the films stored in his Virginia cave, the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, became the very location used as the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center.

The veteran film expert joined the Society of American Archivists in 1948. He was also a source for Hermine Baumhofer’s essay “Motion Pictures Become Federal Records,” in The American Archivist (January 1952). She recounts his work with the Interior Department. “Between 1912 and 1915 all areas set aside as national parks were photographed, the filming and editing being done by Mr. Cowling.” His See America First series, he told her, consisted of 52 one-reelers released by Metro and Gaumont, “the first Government film to be distributed in this manner” (20). Expect to read much more about such work as film historian Jennifer Peterson publishes her latest research about films from the National Park Service.

[Update: video recording (10 min.) of Jennifer Peterson, “Conservation and the State: Film and the National Park Service,” Films of State Conference, University of Maryland Dept of Cinema and Media Studies and the National Archives and Records Administration, April 7-9, 2021. US National Archives YouTube channel, June 30, 2021.

What of the materials Cowling gave to the Library of Congress? Its online catalog has entries for books, films, and photographs credited to Cowling. Only four items are listed as part of a “Cowling (Herford Tynes) Collection.” As Paul Spehr correctly recalls, these are gifts from Cowling dated ca. 1962, and associated with the 1933-34 Chicago fair, aka the Century of Progress International Exposition.

- 1934: The World’s Fair Black Forest / Burton Holmes Films (Kaufmann & Fabry Co., 1934) 16mm, 144 feet, ca. 4 mins.

- 1934–Villages of the World’s Fair, 16mm, 140 feet

- A Century of Progress Exposition — Indian village (Burton Holmes Films in assoc. with Herford T. Cowling, 1933) 16mm, 114 feet; 2 positive prints + duplicate negative.

The fourth item stands apart: East Indian Island (Eastman Teaching Films, Inc., 1930?); Encyclopædia Britannica Films no. 1077 [ca. 1945]) 16mm, ca. 396 feet, silent b/w; + 35mm, ca. 990 feet, 2 reels, tinted, the latter an exchange copy from the George Eastman House. Stock footage licenser Periscope Film has An East Indian

However there are a couple dozen other films of 1933 the LoC catalog says Cowling made and/or donated. Most are from the Century of Progress Expo, such as The World a Million Years Ago, The Fair at Night, Sally Rand [fan dancer], Faith Bacon the Fan Dancer of Hollywood, The Fair from the Air, and Around the Fair with Burton Holmes no. 1 and no. 2. Copies of some of the Holmes Century of Progress films that Cowling shot are online. (His name is never on screen.) The Fair at Night (1933) is on travelfilmarchive’s YouTube channel. Three versions of Wings of a Century are posted from Prelinger Archives, including this 39-minute cut.

Here’s the first Around the Fair film (1933). 8 min.

A minute of Sally Rand’s nude fan dance is part of Streets of Paris (1933).

The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress (Jan. 1964) mentioned only that Cowling donated a “small collection of films made in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia in the 1920’s” (62).

Other pieces are incompletely catalogued portions of Cowling’s nonfiction travelogue work. Several are described curiously as “book,” 16mm, such as

* [Kashmir] [Motion picture] [n.p.] Herford Tynes Cowling, 1923.

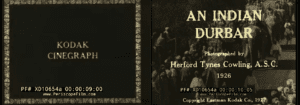

* An Indian Durbar [Motion picture] [n.p.] Burton Holmes Lectures, 1926, a silent 1,200 feet lecture version and a later, shorter sound version. “Shows the coronation of ‘Maharaja Hari Singh of Kashmir,’ March 1926.”

A third version of the latter film circulates online, with a rare on-screen credit for Cowling, copyright by Eastman Kodak Co., 1927.

As recently as this month, YouTubers continue reposting this footage of the “last maharajah,” with comments about the political, religious, and military conflicts over Kashmir. (As I update this post on August 16, 2019, news outlets are reporting multiple casualties today in the disputed region following the Indian government’s revoking the “special status” of Kashmir.)

Both Cowling’s [Kashmir] and An Indian Durbar can be linked to fragments that survive elsewhere. Like other globetrotting camera operators of the era, Cowling shot footage that commercial newsreel services licensed or purchased. The University of South Carolina Moving Image Research Collections reference catalog lists Cowling as the camera operator for Fox newsreel footage originally described by a footage librarian as [Leopard] (three shots taken in 1923) and Coronation of the Maharajah of Kashmir (1926). Portions of both were used in theatrical newsreel releases that do not survive. (Update: in 2020 a change in the library’s online catalog system means these two items are no longer available, not even in text form. The Reference Catalog that I used often to research the “legacy catalog” has now been retired and its descriptions will not be accessible.) However the Fox entry for “Coronation of the Maharajah of Kashmir” shot by Cowling is likely similar to his film Indian Durbar (1926), cited above from the Travel Film Archive stock footage company. Another such vendor, Periscope Film, posts a tinted version with a pre-title card identifying it as part of the new Kodak Cinegraph brand. It provided 16mm prints for home use.

Fox in fact hyped the footage in a puff piece by sales manager Fred Quimby: “Fox News Helps Educate the World,” Exhibitors Herald, Sep. 11, 1926. Without naming Cowling, he boasted of the newsreel’s international reach, saying “a special emissary just emerged from the Vale of the Cashmere, near the Afghan border, where he succeeded in making pictures showing the almost fabulous and barbaric beauty and wealth of the land of the Maharajah of that distant spot.” Other exclusive newsfilm from Cowling included 1924 coverage of warring factions within China.

Thus Cowling’s images were widely seen even if he was not as well known as Burton Holmes.

A final note about the Library of Congress catalog’s clues to Cowling’s films, now orphaned or lost. The entry attributing Cowling as photographer is for 72 photographs on glass lantern slides from 1923. The assigned title is “[Tibet and Asian landscapes and people, includes mountain expeditions, travel on elephants, tiger hunting, Herford Tynes [sic] with dead tiger and posing with his camera].” These are described as unprocessed items in the Prints and Photographs Division, with the note: “Gift to MBRS [Motion Picture, Broadcasting, Recorded Sound] from Col. Cowling. Photographs are probably associated with the filming of Burton Holmes’ To the Roof of the World in Tibet. This catalog record contains preliminary data.”

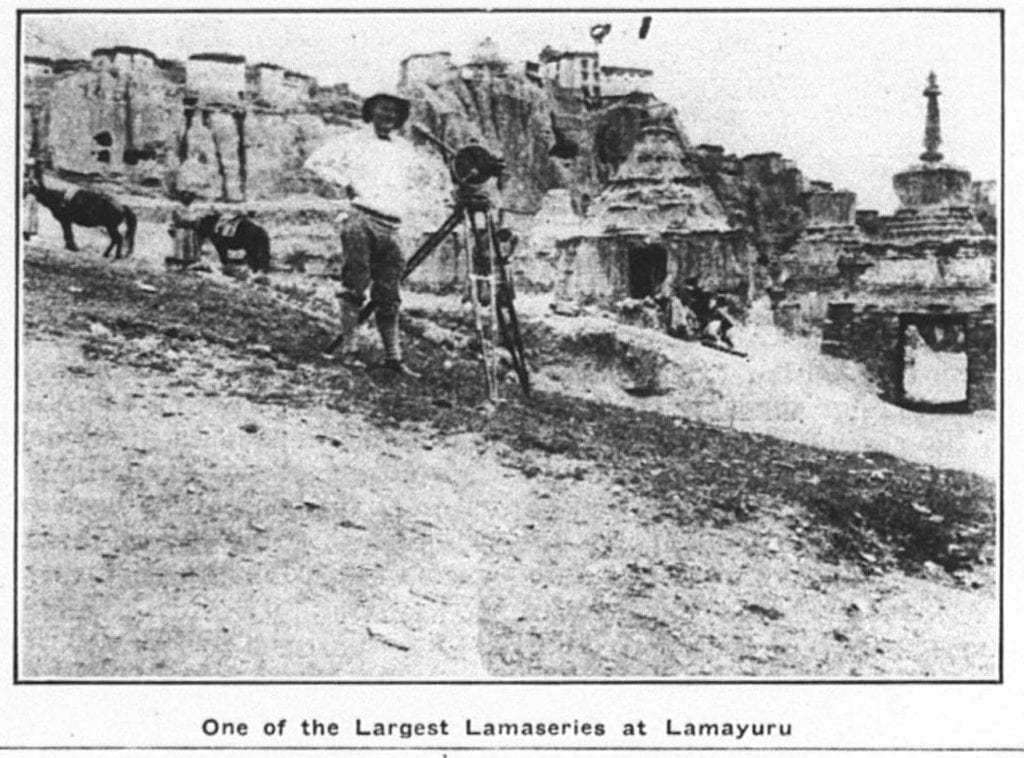

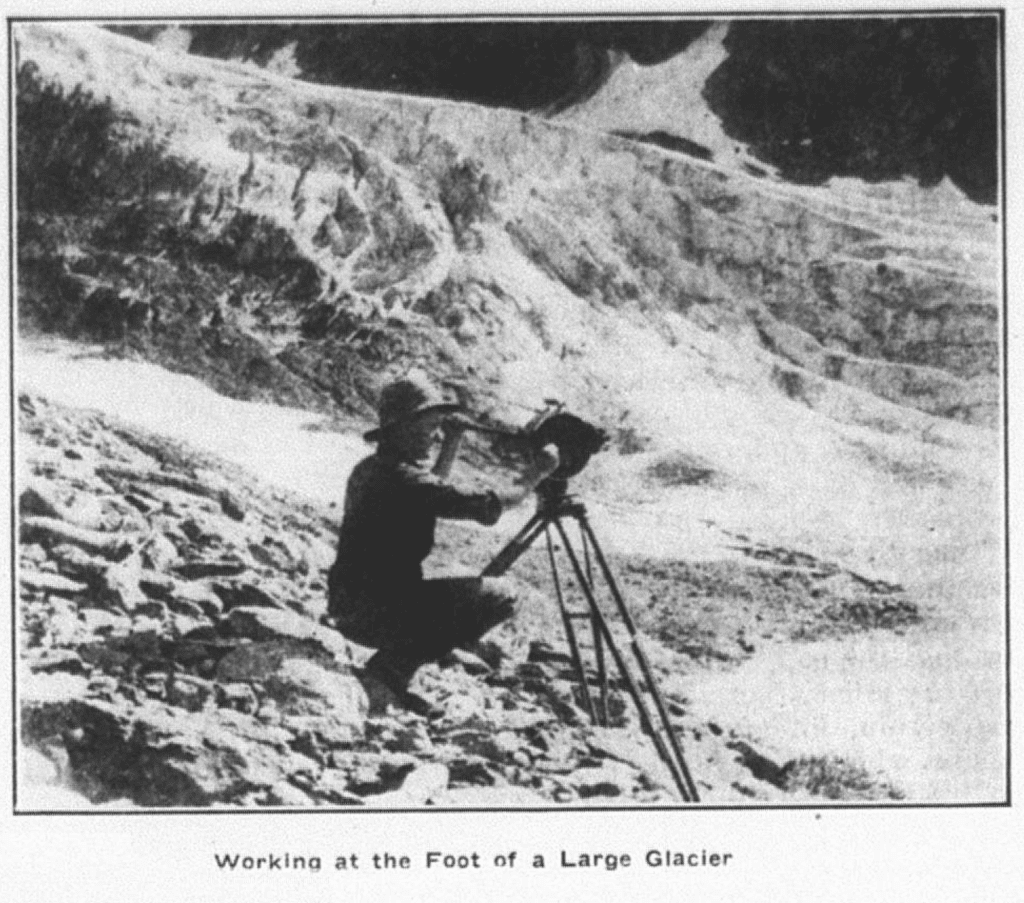

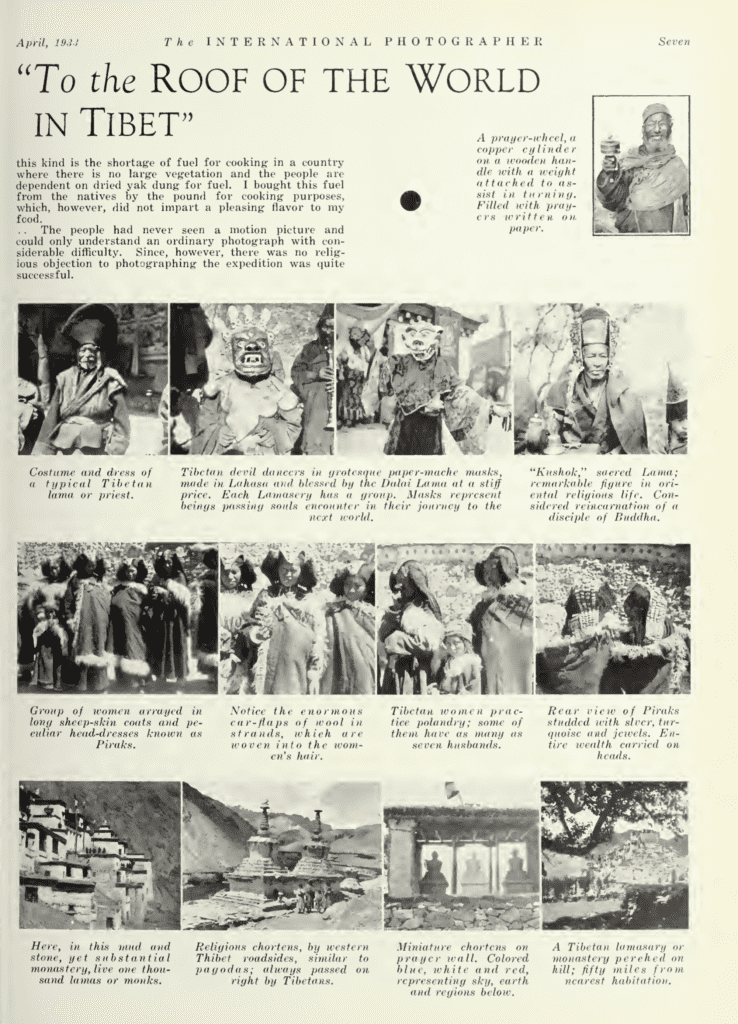

The note is curious in that Holmes filmographies do not include this title, nor any about Tibet. The lone reference I have found to this title is from International Photographer, April 1933. A column by Herford Tynes Cowling, “Around the World, No. 1,” features a page of his 1923 photos under the heading “To the Roof of the World in Tibet.” Are some of these images also on the LoC lantern slides that have yet to be processed? Are these the only remnants of the companion motion picture? Was there a film by that title or was the footage only part of a Holmes travelogue lecture? (The George Eastman Museum houses a rediscovered Holmes collection acquired in 2004, listing 175 items. None mention Tibet or Kashmir.)

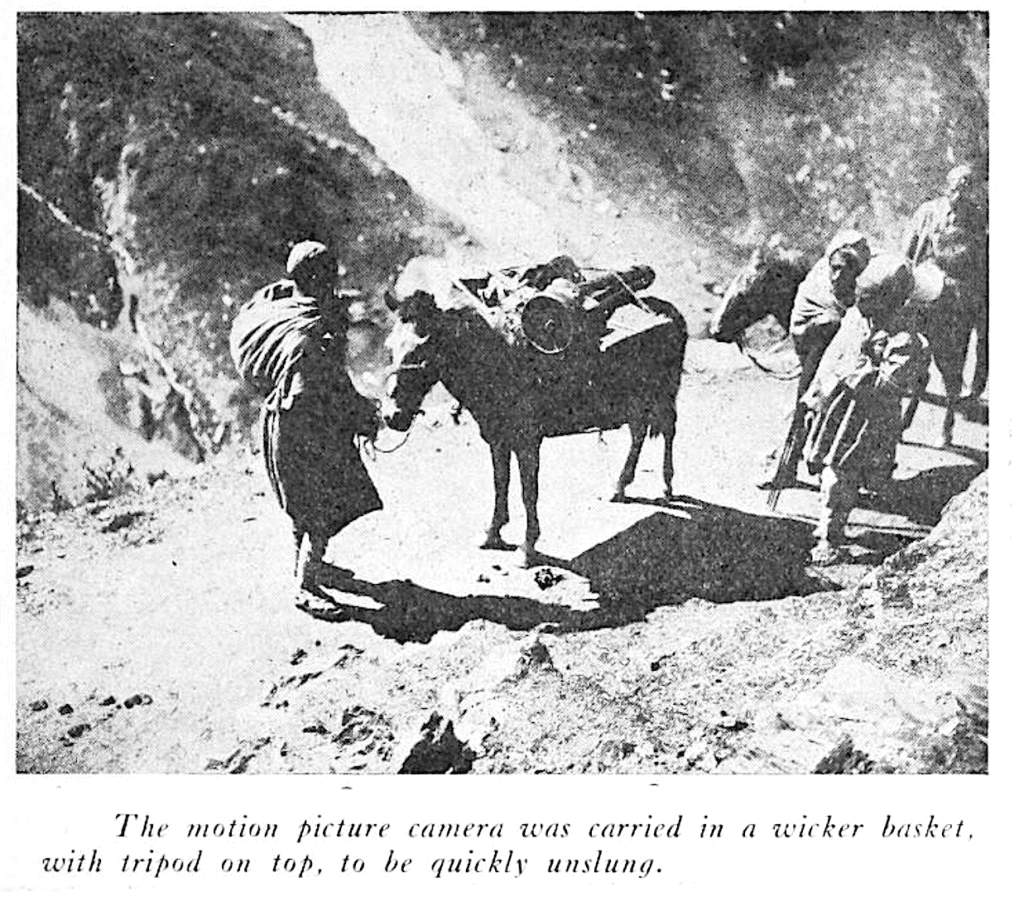

“This [1923 venture] “was the first moving picture expedition ever made into Tibet for the purpose of filming the people and customs of the country,” Cowling claimed in 1933. He refers to “about one hundred thousand feet of film exposed which, incidentally, kept very well at the high, dry altitude” [in re: our subject of cold storage as film preservation]. “About four thousand still pictures were taken during the trip, all of which were developed en route.”

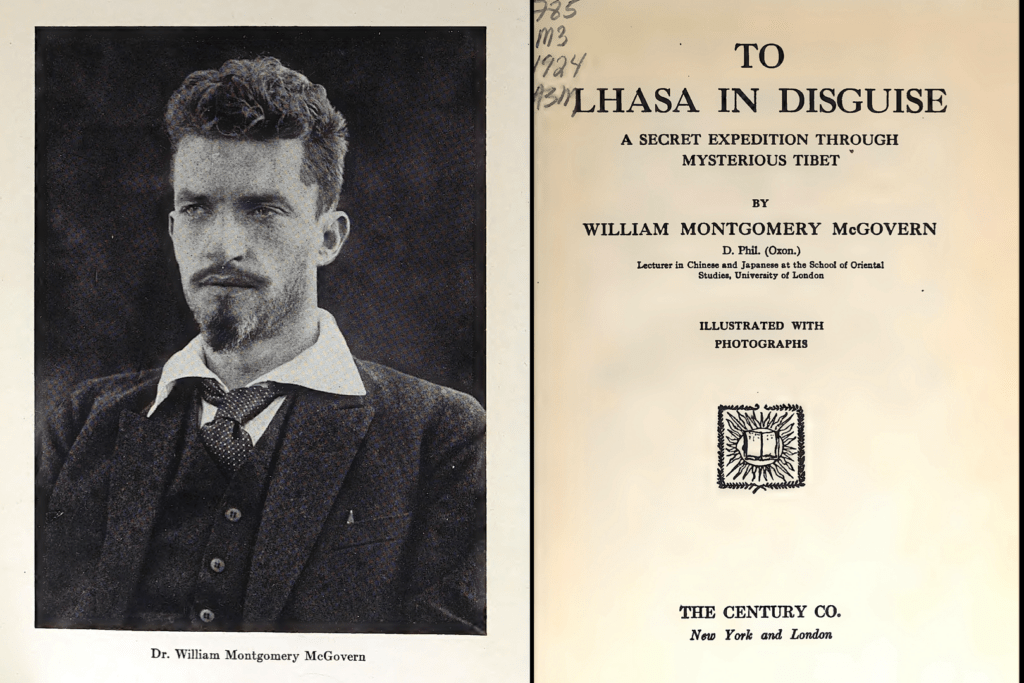

Were these films the first ever shot in Tibet? Certainly they were among the earliest in-depth productions done for that purpose. By the end of 1923, another American returned from Tibet with footage he secured under even more adventurous circumstances. In a future post, I hope to review the somewhat legendary career of scholar William McGovern and his film, To Lhasa in Disguise aka Mysterious Tibet, which debuted in 1923, was released in 1924, later lost, but re-found and restored in 2015 by Cinematheque Suisse.

For now, this establishes an account of how McGovern accompanied a British military crew from India into southern Tibet. When he refused to return to India, in hopes of getting an audience with the Dalai Lama in Lhasa, William Harcourt taught him how to use the outfit’s 35mm camera. “Filming in a Land of Mystery.” Wide World Magazine, no. 6 (1924), 178-185. Here’s the first page.

The online TibetFilmArchive.org, collected in New York by filmmaker and archivist Tenzin Phuntsog, lists only three pieces of extant film from the 1920s, and these are after 1923. In 1928, German scientist Wilhelm Filchner publicly showed some of the footage he shot during his 1925-28 stay in Tibet. His 1929 book, Om Mani Padme Hum [a Buddhist mantra]: Meine China- und Tibet-expedition 1925-8, claimed he shipped 20,000 meters of unprocessed film to Germany. (Was it the new 16mm format?)

Cowling commented in his 1933 account: “The people had never seen a motion picture and could only understand an ordinary photograph with considerable difficulty.”

Such a description of a Westerner’s first encounter with non-Westerners’ first encounter with movies resembles similar accounts of the period. Cowling had been doing such work since the 1910s, but this 1923 expedition came only a year after the release of Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North. As Flaherty and Cowling acknowledged, the communities they photographed participated in the labor of chemically processing the films and photos as they were shot. Cowling describes hiring dozens of Tibetans who made possible his four-month trek through the mountains via yak. Thus the contradiction in his account that Tibetans “could only understand an ordinary photograph with considerable difficulty,” even though teams in his employ helped process thousands of photographs.

McGovern’s account of his 1923 trip to Lhasa contradicts Cowling’s. His popular book To Lhasa in Disguise reported the Dalai Lama’s chief aid made a hobby of “amateur photography,” decorating this room with family photos.

The LoC online catalog offers only one photograph in the HTC Collection.

The title assigned to it is [Lama with headdress and Caucasian man seated in front of nine boys and men, Tibet]. The “Caucasian” man is Cowling himself. Who took the photo? (or is that a shutter release cable in his right hand?)

More important, what happened to the 20 hours of footage he shot in Kashmir and Tibet? and is there a film called To the Roof of the World in Tibet that might survive under different titles or within later film compilations?

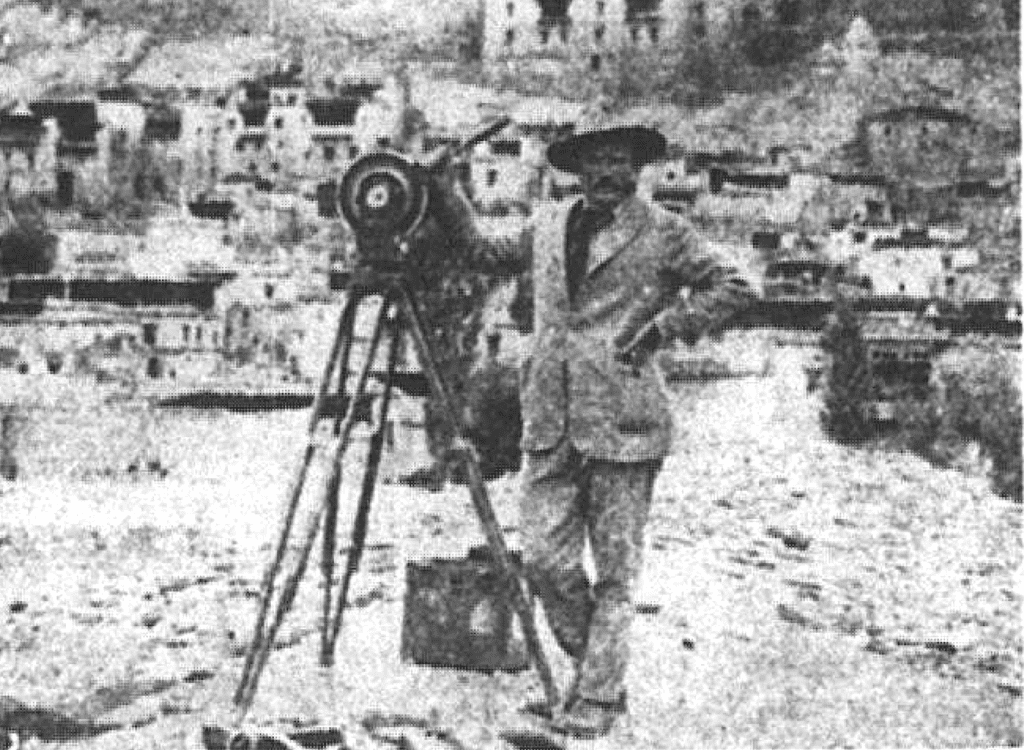

The best photographic evidence comes from the International Photographer piece and his more contemporary account in American Cinematographer (Feb. 1924), “Photographing the Roof of the World,” by “Herford Tynes Cowling, A.S.C.” The first page of this is missing from the online copy, but the Long Island University Post library digitized its microfilm copy on request. Here is some of the photo-documentation of H. T. C. at work with his 35mm Akeley movie camera.

“I believe I have secured the only existing films of this nature.”

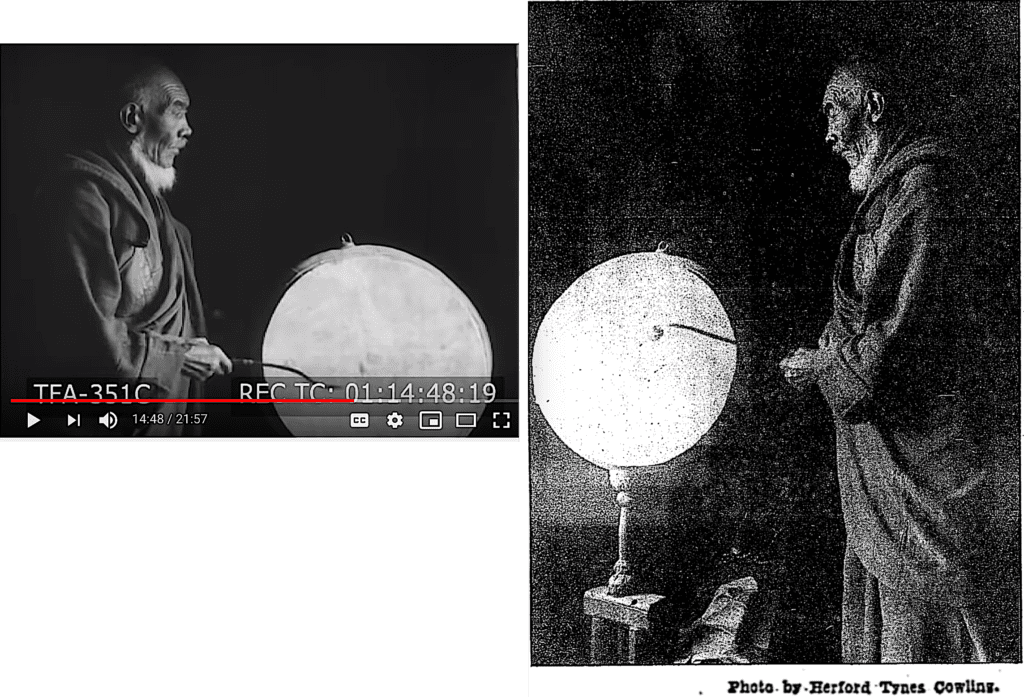

He contributed another short piece, “How the Pandita [Buddhist spiritual leader] Was Photographed,” American Cinematographer (April 1925). He describes how Tibetan and Kashmiri workers helped him set up the movie camera and introduced him to the Pandita who gave permission to film people.

Pages harvested from lantern.mediahist.org.

According to the Exhibitors Herald, the 1923 Tibetan expedition was facilitated by Hari Singh, who “later commissioned Cowling to officially photograph his coronation” in Kashmir — “though it was to rest only in Sir Hari’s private archives” (“Fame of A.S.C. Spreads,” Sep. 4, 1926). Cowling published his own accounts of the coronation film as an elaborate work for hire. (“A Modern Ruler in the Vale of Kashmir,” New York Times, Feb. 27, 1927; “A Washingtonian Grinds the Camera as India Crowns a New Ruler in a Pageant Costing Millions,” Washington Post, Sep. 16, 1934.)

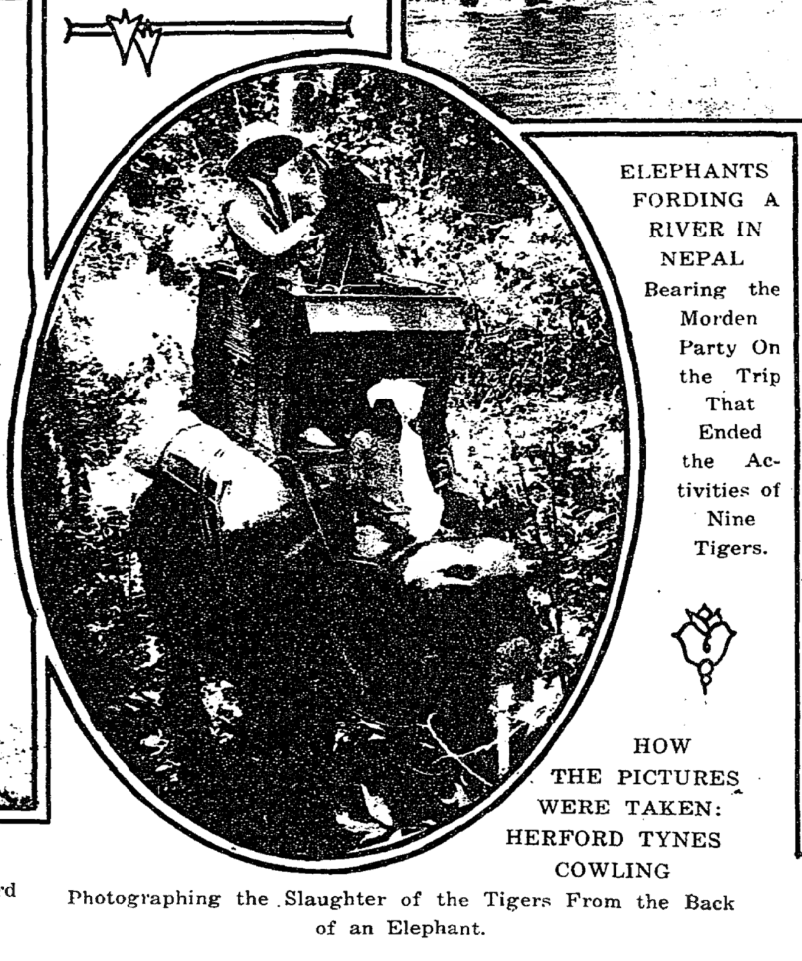

He’d taken other camera commissions, filming, for example, an elaborate 1924 hunting expedition in Nepal and India for the wealthy “Mr. and Mrs. W. J. Morden of Chicago.” The New York Times and many others ran rotogravure spreads of Cowling’s stills, including this one of him “photographing the slaughter of the tigers from the back of an elephant.”

He published his account in “Around the World, No. 2: Filming a Tiger Shoot in India,” International Photographer (May 1933). The column ran for six issues, then was reworked for a series in the Washington Post Magazine in 1934.

Again the question remains: what became of the motion-picture film he recorded on these trips? His writings do not address the issue.

For most of the 1920s, Cowling traveled the globe, shooting for Holmes for seven years (1917-1923) and then for his own Round-the-World Travel Pictures. American Cinematographer often mentioned the travels of the American Society of Cinematographers member, who upon his return in 1929 served on the journal’s advisory board.

When his globetrotting ended, Cowling returned to Virginia and federal employment in D.C. as a technical consultant on motion pictures (and microfilm) for the National Archives, National Parks Service, Bureau of the Census, the military, and other government bodies. See Official Records of Herford T. Cowling, 1937–1938, “who served with the unemployment census, first as motion picture consultant and later as technical assistant in charge of microfilming the records of the census. The records consist of correspondence with the National Bureau of Standards and commercial microfilm companies, minutes of meetings, and reports relating to standards for the content, processing, and storing of microfilm; and interoffice memoranda, invoices, and inventories of supplies for microfilming the unemployment census records . . . none of which are available online.”

Returning to the relevance to orphan films about climate and migration: Even during his active shooting years Cowling published technical advice about how film needed to be treated in cold and hot climates. See his article “Film Care in the Tropics,” for example, in the August 1927 issue of Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. That so much of his shooting took place in diverse geographies, recording landscapes, mountains, glaciers, rivers, islands, and jungles makes these films prime examples of how we might re-examine newsfilm, travelogues, and their unedited footage for what they captured of these places a century ago.

American and European travel films of that era are now often noted for their “bad anthropology,” xenophobic commentary, and photographic othering of people filmed in non-Western parts of the world. Without Cowling’s theatrical releases to examine, we cannot fairly analyze them. Certainly his brief written comments in trade journals and the press often resort to the word strange (and sometimes worse) to characterize the people and places he encountered in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Pacific islands. He never claims cultural expertise or anthropological mission. He was seeking spectacular scenes for American movie audiences, he says. His writings are often sympathetic to his subjects, expressing admiration for traditional cultural practices he observes. Cowling writes without judgment, for example, about polyandry (he uses the word) and female-led communities he saw in Tibet.

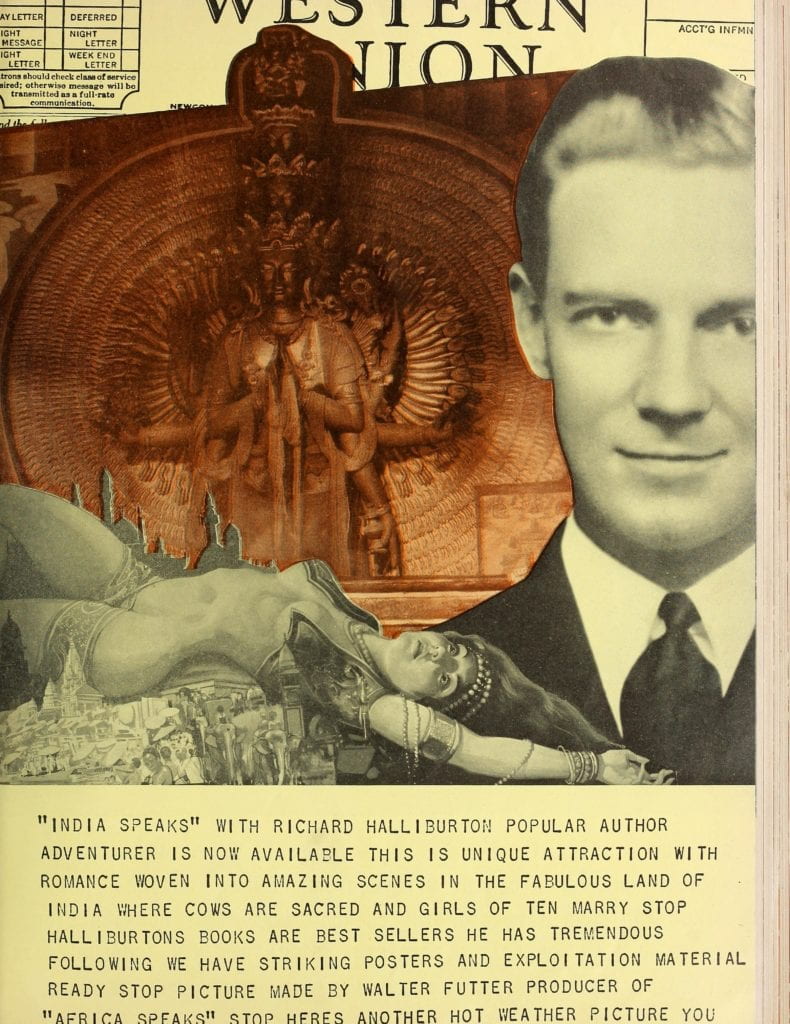

Without trying to make the case for Cowling as an exceptional filmmaker or sensitive ethnographer, we might conclude by noting his public protest over Hollywood’s abuse of his travelogue footage. He licensed his footage of Tibet and India for use in the RKO release India Speaks (1933), which lists him in the credits as one of three photographers. The movie intercuts genuine location footage shot by Cowling and others with fictional scenes staged in Hollywood, all narrated by travel writer and adventurer Richard Halliburton.

The exploitation film presents India as a land of ritualized sin, orgies, crime, and violence. Cowling strongly objected to its misrepresentations. “They have taken scenes made in Burma, Java, Sumatra and other places and put them in Tibet and India with no regard for geographic truth.” They took his footage and “faked a fight between a lion and a tiger.” He complained to the Federal Trade Commission, the Hays Office, and newspaper reviewers. (“Film Fakers,” International Photographer, June 1933.) But the movie enjoyed wide release — except in England and India, where exhibitors refused to show it. A March 1939 FilmIndia editorial — “This Slander Must Stop” — complained about misrepresentation of Indians in RKO’s new re release Gunga Din (1939). It recalled called the rejection of India Speaks on the subcontinent, while “the rest of the world – the white world to be accurate – received the picture with enthusiasm,” and “got through the American ‘keyhole’ a cock-eyed peep of India and her ‘natives.'”

Can Cowling’s footage of Tibet, Kashmir, and India be seen in India Speaks? It had long been deemed a lost film. But . . . just three months ago, May 24, 2019, the Travel Film Archive, a footage licensing company, quietly posted 55 minutes from India Speaks on its YouTube channel, in three parts. The 1933 release ran 78 minutes. TFA founder Patrick Montgomery, veteran of archival film collecting and licensing, bought 35mm prints of both Africa Speaks (1931) and India Speaks on eBay. A 1941 RKO reissue version, retitled as The Bride of Buddha, 63 minutes, survives as a nitrate print at the UCLA Film and Television Archive.

Indeed many of the shots of Tibetan locations, ceremonies, and lamaseries mirror the stills published as “To the Roof of the World in Tibet” (above). Perhaps Cowling disseminated these in April 1933 precisely because the Hollywood movie that desecrated his handsome footage was released that same month.

Other scenes in India Speaks match Cowling pictures of the 1926 coronation in Kashmir. Compare, for instance, this frame from India Speaks (left) to a Cowling photograph (right) the Washington Post used to promote his article about the coronation (Sep. 15, 1934).

Other Cowling films may yet be located and identified, but now we know that some of his most widely seen cinematography is no longer completely lost.

Watching India Speaks confirms why Cowling was so displeased with how his images were appropriated and exploited. It’s a cringe-inducing movie.

“The striking posters and exploitation material” RKO boasted of in its trade promotion further reveal how lurid and sexualized the images of India were.

. — Motion Picture Herald, May 27, 1933.

. — Motion Picture Herald, May 27, 1933.

“‘Horrific’ Film About India,” ran the Times of India headline of April 11, 1948, when the American producer re-applied to London censors to permit exhibition of his self-described “horrific” documentary. (Reference provided by Navnidhi Sharma, who in a fortunate convergence is writing a dissertation on “a history of encounters between Indian cinema and China.”)

After subsequent research, I plan to write further about the competing claims by several to have been the first to film inside Tibet.

NOTES ABOUT THIS:

Indeed there were several commercial news pieces or travelogues throughout 1923-26. Among the earliest appeared in International News No. 22, with “Lhassa. Thibet. Thibet’s ‘dancing devils’ welcome the New Year,” (Motion Picture News March 24, 1923, 1488).

Gene Lamb:

This recycled newsreel from a 1948 television series called Yesterday’s Newsreel labels one segment as “Fobidden City of Tibet,” claiming the footage is from 1923, shot by Gene Lamb for a Nicholas Roerich expedition.

Although Lamb was not affiliated with the well-known Roerich, the newsreel photographer indeed spent several years in China in the 1920s and traveled to Tibet in 1923-24. He was at times part of the American Museum of Natural History’s Trans-Asia Photo Scientific Expedition of 1924, led by Roy Andrews Chapman.

A 1925 newspaper profile of Lamb and Corrinne Goodknight described their honeymoon to China, followed by two “Thibetan excursions,” two months travel to the Tsaidan plains and four months in which they failed to reach Lhasa. Lamb returned to the U.S. with 30,000 feet of film, much of it described only as beautiful shots “unlike the usual travelogue.” (“Spokane Girl’s Honeymoon Tour to Tibert,” Spokesman_Review, July 5, 1925.) It’s not clear if Lamb attempted to release a production of his own, but the Kingorams newsreel service included several segments in its weekly releases: “Gene Lamb, Kinograms Newsman, Films Industrial Activities of Natives of Thibet,” no. 5151 (1926). “Tibetan Mountains Are Crossed for the First Time; Gene Lamb, Kinograms camerman, lead the only white expedition to conquer Alexander III range; a Kinograms exclusive,” no. 5156 (Jan. 1926); “Gene Lamb Wins Kingram Honor, Exhibitors Herald, April 10, 1926.

Gene Lamb, “The first man to visit and film forbidden Northern Tibet,” Lyceum Magazine, Sept. 1926.

Kermit Roosevelt Expedition to Tibet and Bhutan (1926) released with the cooperation of the Field Museum of Chicago

In 1919, Carl Laemmle announced Universal would undertake a far east expedition to include film in Lhasa, where “only ten white men have ever set foot within the city.” Moving Picture World, July 26. 487-88.

Early films referencing Tibet and Thibet.

The Llamas of Thibet (Urban, 1903)

Sul tetto del mundo [The Roof of the World (1909-1910) [Travel of Duke of the Abruzzi in the Karakorum]. Vittorio Sella “500 yards of cinematograph films”

Les Fêtes religieuses au Thibet (1910) Éclair

Danses sacrées au Thibet (1911)

On the Frontier of Thibet (1911) Urban-Eclipse

An Excursion into Thibet (1912) Lyman Howe

The Frontier of Tibet: The “Forbidden Land” (New Era Films, 1920)

William Montgomery McGovern’s book To Lhasa in Disguise: A Secret Expedition through Mysterious Tibet (1924) and the film documentation he made.

— Dan Streible

(updated Aug. 23, 2019; edits Feb. 21, 2024)

Preview photos:

To be continued. . . .

___________

Notes:

• Michael R. Pitts, RKO Radio Pictures Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Films, 1929-1956 (McFarland, 2015) well describes the history of India Speaks, but deems it a lost film (as do Wikipedia and IMDb at the moment).

• While in China, Cowling was interviewed about his Tibet shoot and Nepal tiger hunt. (“With the Movie Camera in Farthest Tibet,” North-China Herald and Supreme Court, Oct. 4, 1924.) He also recounted events in his own article, “In Tibet, Strange Land of Beauty and Ignorance, Women Rule ‘The Roof of the World,’” Washington Post, Oct. 7, 1934. Upon returning to North America, he told of filming conflicts among Chinese military cliques, particularly those commanded by generals Wu Peifu and Feng Yuxiang in September-October 1924. (“Pictured Actual Fighting Along Chinese Battle Fronts with 8,000 Feet of Camera Film; H. T. Cowling Had Thrilling Experiences While Watching Chinese Factions in Warfare,” Victoria [BC] Daily Times, Nov. 18, 1924.)

• The Travel Film Archive online offers two other short films about Tibet, which could possibly include Cowling footage. The Unknown World, “an expedition in the 1930’s [?] to see the Dalai Lama” in Lhasa, Tibet. The title is another unknown one. The end credit, “A General Film Productions Corp. Picture,” identifies this as a post-WWII nontheatrical edition for television. “Adapted by Tom Terriss” refers to the host of a film and radio travel series, Vagabond Adventures (1927-34), who developed postwar television content. I have found no evidence of the title The Unknown World in distribution in the 30s; much of the footage appears to be from the 1920s. Easier to verify is the travelogue Tibet: Land of Isolation (FitzPatrick Pictures, 1934), an MGM theatrical release. Although contemporary with India Speaks, most of the FitzPatrick footage appears distinctive. (Historian Peter H. Hansen assays: “Although it is unclear where the film was shot, the soundtrack is more Chinese than Tibetan in inspiration. . . a visual catalogue of many Western myths about Tibet.” Hansen makes this indispensable 2001 essay “Tibetan Horizon: Tibet and the Cinema in the Early Twentieth Century” available for free download.)

• The Travel Film Archive lists 2,851 digital video items in its collection. Only one, An Indian Durbar (1926), is credited to Cowling.

• Where do TFA films come from? The website calls them “a collection of travelogues and educational and industrial films” shot on film between 1900 and 1970. Stock footage entrepreneur Patrick Montgomery began building this and other thematic collections in 2007. Previously he created Archive Films, for a time the largest U.S. stock footage company until acquired by Kodak’s The Image Bank in 1997 (which in turn was purchased by Getty Images in 1999).