A Preview of the Unveiling of a Parade in Taiwan, 1930

by Siyi Quan (NYU Cinema Studies)

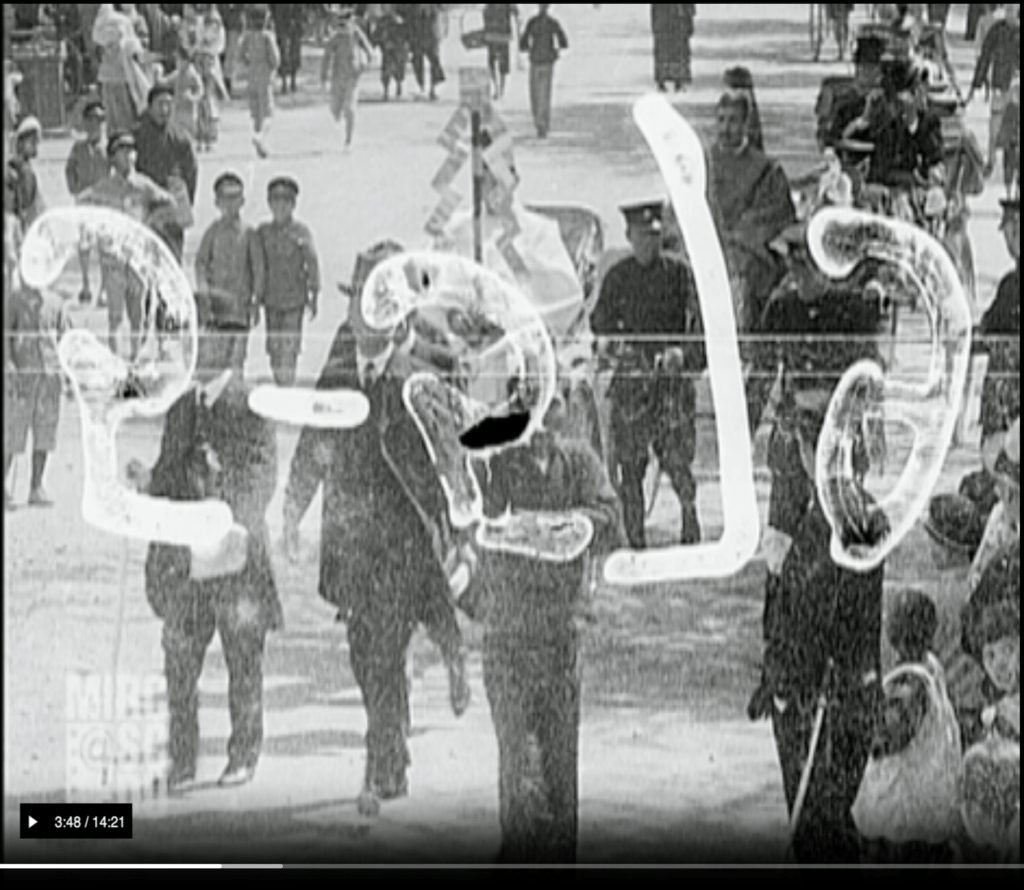

At the 2024 Orphan Film Symposium, Klavier Wang, an assistant professor at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University in Taiwan, presents new research done with graduate student Yung-Cheng Yen. In her talk “Unveiling the True Face of a Parade” she will screen Fox Movietone News footage filmed on the island of Taiwan in 1930 and discuss the complexities of public life in occupied Formosa.

The University of South Carolina’s Moving Image Research Collections catalog assigns the unedited newsfilm the title Formosan New Years procession / parade – outtakes. It documents that camera operator Eric Mayell (with sound recordist Paul Heise) shot the 35mm black-and-white film on February 15, 1930.

The library record offers this summary description: “Scenes of a New Years Procession in Formosa (Taiwan) under Japanese colonial rule. Includes spectators. Children wearing traditional costumes, being pulled in rickshaws. Children carrying banners and bands. Priests carrying drums and banners. Men carrying portable shrines. High shot dignitaries being pulled in rickshaws. More of parade.”

Previewing this on the archive’s website, indeed reveals a grand scene, with large numbers of performers and participants. Bands of musicians play on classical percussion instruments throughout, giving a vibrant and lively atmosphere. (We also hear someone behind the camera briefly speaking Japanese.)

We invite you to experience this film on the big screen, with a first look at a new 3.5K scan of the original nitrate film, made by MIRC Greg Wilsbacher for the ocassion. On Thursday, April 11, Prof. Wang’s presentation concludes the 2:15 pm session “Moving Image Technologies at Work, in Asia.” The other talks are by Eric Faden and Jackson Rubiano (Bucknell University) “Preserving and Presenting Japanese Paper Films,” and Ann Lyuwenyu Zhang (NYU) and Dino Everett (University of Southern California) “Thinking Out of Sync: A Presentation of the Chinese Obsolete Film Format 8.75mm.”

Addendum: Photographic evidence

Inspired by Wang and Yen’s research, I was curious about the USC MIRC catalog’s description of “portable shrines.” What were these in the context of 1930 Taiwan?

In 1895, after victory in the first Sino-Japanese War, the Empire of Japan began its fifty-year occupation of Taiwan. After 1936, the “Kōminka movement” (皇民化运动) to make islanders subjects of the emperor, religion emerged as one of the key components of “Japanization,” alongside language, education, and military service. Occupation brought Shinto, the predominant religion in Japan, to Formosa/Taiwan. During the peak of Japanese influence, more than 400 Shinto shrines were set up across Taiwan. (Wei Lin Cheng, “The Current Status and Development of Japanese Studies in Taiwan: From a Folklore-Centred Perspective,” Japanese Review of Cultural Anthropology, vol. 20, no. 2 (2019): 147.]

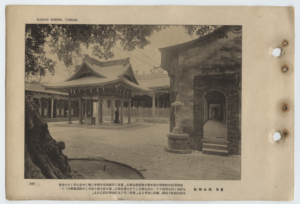

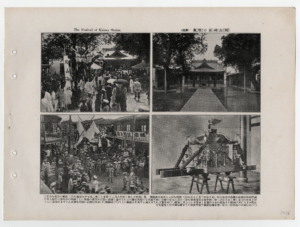

A rich resource for the study of Taiwan of this era is housed at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania. The Lafayette Digital Repository provides access to the East Asia Image Collection and the Gerald & Rella Warner Taiwan Negative Collection. U.S. Consul to Taiwan Gerald Warner and his wife Rella created 369 photographic negatives during 1937-1941. Also in this East Asia collection are 468 images from the monthly magazine Taiwan shashinchō / 台湾写真帳 (Taiwan Photograph Album) published in the 1910s. These document Japanese structures on the island.

Below is a sampling.

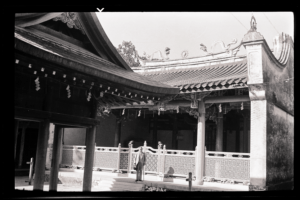

Below: Three images from Gerald and Rella Warner, dated 1939-40.

Finally, I found undated photo from a Chinese-language source, the Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank, memory.culture.tw.

Siyi Quan is a student in the M.A. program in the Martin Scorsese Department of Cinema Studies, part of the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University.

Notes: Based on the description of the two photos and the synopsis provided by Prof. Wang, it can be inferred that the Kaizan Shrine parade depicted in the film is the same Japanese shrine located in Tainan City, as shown in the photos. It bears the same name written in Kanji 漢字: “開山神社”. Indeed, the annual festival at this shrine takes place on February 15th.

Originally constructed in the 17th century as a Chinese-style ancestral shrine to honor Koxinga, known as the Koxinga Shrine. In 1699, worship of Koxinga was banned by the government, leading people to secretly continue their worship of him. In 1897, during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan, the shrine was converted into a Shinto Shrine and renamed Kaizan Shrine (also known as 開山神社, Kaizan Jinja, Kaishan Jinjya). In the 1960s, the shrine was transformed into a Confucian temple.

(Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koxinga_Shrine