Kol Nidre (nidrei, nidrey, or כל נדרי) is an Aramaic phrase translated as “all vows.” The words are heard and chanted in synagogues on the eve of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement in Judaism. In 2022, “Kol Nidre night” falls on October 4. (Hebrew calendar: Tishri 9, 5783). Music associated with the text has been around a thousand years. Recordings of pieces entitled Kol Nidre began well over a century ago.

Musical settings for the traditional chant have taken many forms over centuries. Some twenty-first century artistic uses of the tradition have crossed paths with orphan film work, which led me to track a kind of media archaeology of Kol Nidre recordings. Many historical recordings have appeared online since this process began, particularly at the University of California Santa Barbara’s Discography of American Historical Recordings, the Recorded Sound Archives at Florida Atlantic University Libraries, and the Center for Jewish History in New York. And in this update we should add “The Great 78 Project,” a mass digitization success story. George Blood, L.P. and the Internet Archive are working with other communities and collectors to provide high-quality audio files taken from 78pm shellac discs (1898 to 1957). Thus far it’s 350,000 items, including a couple dozen Kol Nidres.

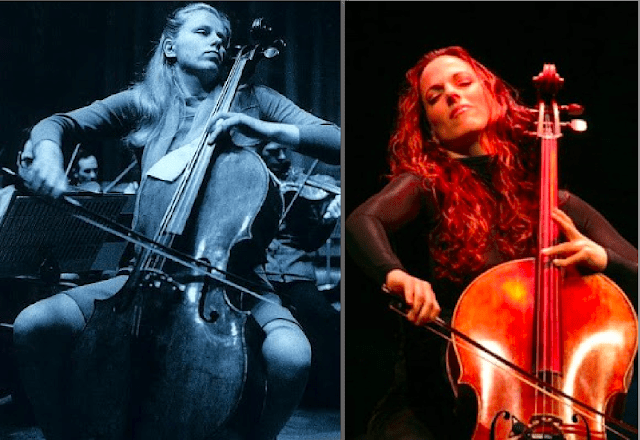

In 2013, Indiana University Cinema and IU Libraries Moving Image Archive hosted an ambitious inter-year NYU Orphan Film Symposium, “Orphans Midwest” Materiality and the Moving Image. The opening event was “Films for Cello,” an evening with filmmaker Bill Morrison and cellist Maya Beiser, highlighted by the world premiere of their 10-minute collaboration All Vows, inspired by Michael Gordon’s composition of the same name.

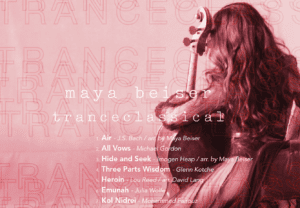

In advance of the IU symposium, and with Yom Kippur 5774 approaching, I published a blog post about the forthcoming film, which grew into an exploration of audio and audiovisual recordings made over the past 120 years. In 2016 I updated it again when Maya Beiser released TranceClassical, an album with a new recording of Michael Gordon’s “All Vows” and a new piece called “Kol Nidrei” (with Lou Reed’s “Heroin” in between).

The new interpretation is from composer Mohammed Fairouz and features Beiser singing the Aramaic text.

The new interpretation is from composer Mohammed Fairouz and features Beiser singing the Aramaic text.

Since the original blogger.com site might disappear at Google’s discretion, I republish — and greatly expand — the piece here. This edition was updated on September 16, 2021 and again today.

— Dan Streible, NYU Cinema Studies

“ALL VOWS: a sneak peek + Historical Recordings of Kol Nidre,” August 24, 2013, orphanfilmsymposium.blogspot.com/2013

updated Septembers 2016, 2020, 2021, and October 2022.

Bill Morrison‘s 2013 film-to-HD transmogrification of materiality into the ineffable, All Vows, finds moving images to accompany composer Michael Gordon‘s musical composition of the same name. Cellist Maya Beiser, for whom Gordon wrote “All Vows,” premiered the work in 2006 at Zankel Hall in New York.

The New York Times review noted: “Electronics play a more vital role… in Michael Gordon’s ‘All Vows,’ a reimagination of Kol Nidre, the central prayer of the Yom Kippur service. Ms. Beiser played a plaintive, arpeggiated line amid a variegated electronic cloak woven mostly of voices, and against an attractively simple video by Luke DuBois.” — Allan Kozinn, “A Conversation of Cultures, Spoken Through a Cello’s Voice,” March 11, 2006.

I haven’t seen Mr. DuBois’s attractively simple video. But it’s safe to say (based on DuBois’s videos — 81 of which are excerpted here — that Mr. Morrison’s source materials and aesthetic bring a much different visualization to the Gordon-Beiser piece. Both media artists have collaborated with the Bang on a Can All-Stars (see again Gordon, Beiser) on multimedia musical presentations. But DuBois works more closely with computer music and digital video [and, I didn’t know at the time, is NYU professor of Integrated Digital Media]; Morrison with film qua film: nitrate cellulose material, infamous for its unquenchable flammability and chemical decomposition. It was that decaying quality that brought forth the Gordon-Morrison collaboration Decasia, one of the most celebrated experimental film works of the new century [and added to the National Film Registry in 2013].

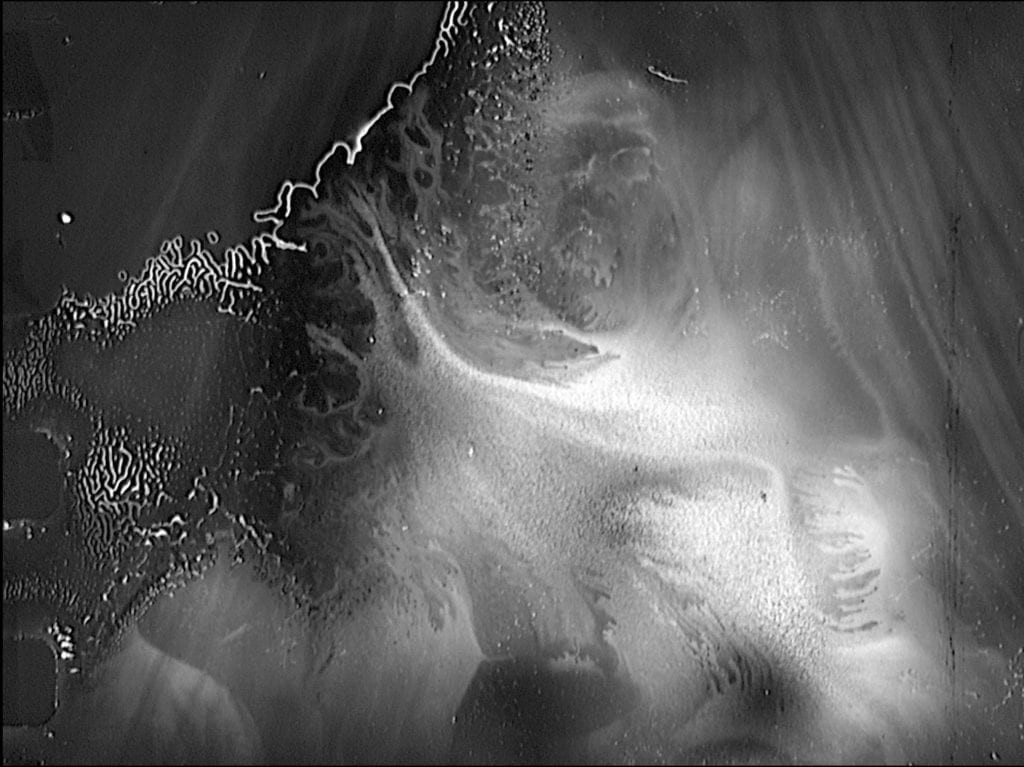

For the spiritual, religious, ancient, reflective, somber substance of Kol Nidre, Morrison’s return to images taken from decaying 35mm films makes sense. As momento mori, few things conjure up thoughts of mortality better than a life recorded on film curiously decomposing. Although the chemical break down of emulsion lying on a nitrate base can lead to the erasure of any recognizable trace of an original photographic image, Morrison’s images are seldom abstract. Moments are carefully selected for their uncanny impact.

Few things more ghostly or, in this case, we might even say scary. Only a phantom of a human figure remains. Nothing digitally manipulated in these swirls and naturally occurring “brush strokes.”

An added note (2020): The principal image (still and moving) in All Vows is taken from Paramount newsreel outtakes showing the Library of Congress exhibit of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1965.  The footage is housed at the Library of Congress and was brought to Morrison’s attention by LOC archivist George Willeman. Shot after the nitrate era, the black-and-white acetate film’s decomposition includes bursts of solarization. All Vows begins (and ends) with shots of a scroll unfurled and human hands guiding the view. As a finger points, bursts of light flicker around edges of the parchment and finger, as if ignited by supernatural effect when the scroll is touched.

The footage is housed at the Library of Congress and was brought to Morrison’s attention by LOC archivist George Willeman. Shot after the nitrate era, the black-and-white acetate film’s decomposition includes bursts of solarization. All Vows begins (and ends) with shots of a scroll unfurled and human hands guiding the view. As a finger points, bursts of light flicker around edges of the parchment and finger, as if ignited by supernatural effect when the scroll is touched.

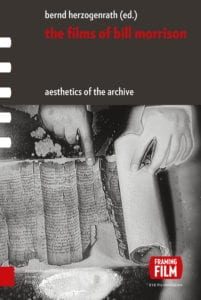

Although All Vows is not one of the works with a chapter devoted to it, the poetic image illustrates the cover of the book The Films of Bill Morrison (University of Amsterdam Press, 2015).

To return to the musical qualities of the traditional Kol Nidre invocation of Yom Kippur, since a Beiser recording of Gordon’s “All Vows” is not yet available [until 2016, when she posted it to her YouTube channel], we can prepare for it with a reminder of other musical interpretations. And indeed to a landmark of cinema.

Below is singer Al Jolson’s Kol Nidre, in a semi-synchronous portion of what is often mistakenly referred to as the first “talkie.” Two minutes from The Jazz Singer, with the jazz singer Jack Robin honoring his cantor father’s dying wish, returning to his synagogue as Jakie Rabinowitz.

Twenty years later, Jolson released this remarkable recording, “Kol Nidrei” on Decca Records. (The flip side of the 78rpm disc is entitled “Cantor on the Sabbath,” sung in Yiddish.) The basso reach of Jolson’s voice is the unexpected part. He was then 61.

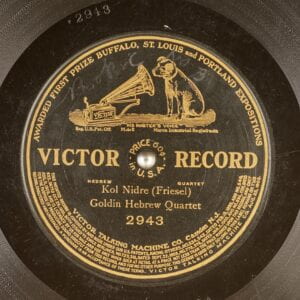

However, well before The Jazz Singer, many sound recordings had been cut of singers and instrumentalists performing many settings of Kol Nidre. As early as 1901, Frank Seiden attempted to make a record at Victor studios in Camden, New Jersey, but they were deemed “defective.” In 1903 Edison cylinders were released of his Kol Nidre; in 1904 Victor issued another Seiden take on 7- and 10-inch discs.

The earliest version I’ve find online is another from 1904. The Goldin Quartet, male vocalists singing in Hebrew, were listed by Victor as the Goldin Hebrew Quartet. The surviving audio sounds about like this well-scratched eBay disc looks. However . . . [update 2022], a considerably cleaner audio edition is now available from the Great 78 collection. It’s the same recording but from a different edition of the disc.

The Wikipedia entry links to a recording issued as Zonophone A 60, by August van Biene on cello, “circa 1908.” Other sources say 1911 or 1912. Here the gramophone collector EMGColonel shows his 12″ disc playing “Kol Nidre” Cello with Piano Played by Auguste van Biene.

He comments “How amazing!” upon hearing what he calls “ghost” voices at the end of the recording.

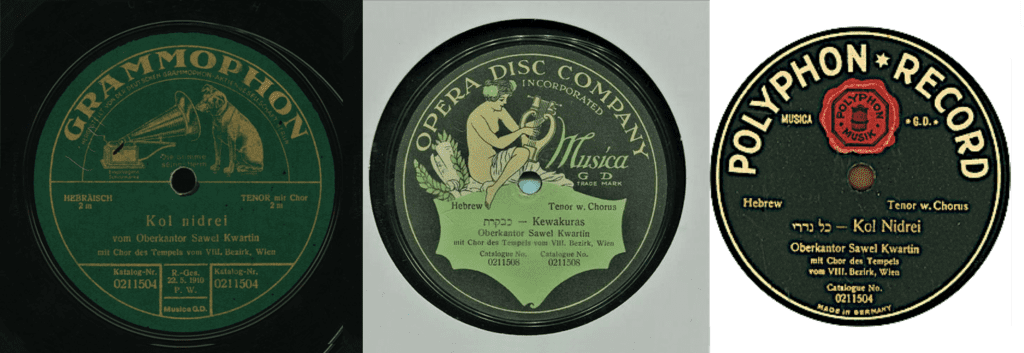

The 1909 Vienna recording, “כל נדרי — Kol Nidrei” by Cantor Sawel Kwartin and a temple choir was well circulated in Europe and the U.S. It was issued on at least three commercial labels, each with the same catalog number. Two different discs have been digitized for online listening. The Center for Jewish History audio is from the Grammonphon label. The Florida Atlantic University Recorded Sound Archive audio uses the Polyphon Record in its Judaic Collection.

Kwartin’s later recording is also in the RSA online collection. “Kol Nidre, parts 1 and 2” runs 8 minutes on the CD self-produced in 2000 by the Judaica Sound Archives, Cantor Sawel Kwartin (1921-22) Vol. 9. It’s also here:

As of 2020, the RSA lists 82 tracks for “Kol Nidrei,” 276 tracks as “Kol Nidre,” and 10 “Kol Nidrey.” Here is the earliest cello rendition, Pablo Casals’s “solo on violincello” (Columbia, 1914). Two sides of the 12-inch 78pm disc. He also recorded versions in 1915, 1923, 1928, and 1936.

Elsewhere, here’s the sublime Casals recording of 1923.

The University of California Santa Barbara’s Discography of American Historical Recordings, lists dozens Kol Nidre records issued before World War II. Among the early acoustic one are Bernard Woolff, tenor vocal with chorus (Columbia, 1911); Maud Powell, violin solo (Victor, 1913); and this cello solo by Leo Schultz (Columbia, 1914), done a month after Casals.

I’m fond of this accordion rendition by Max Yenkovitz (Columbia, 1913), issued with labels for two markets, Jewish and Serbo-Croatian.

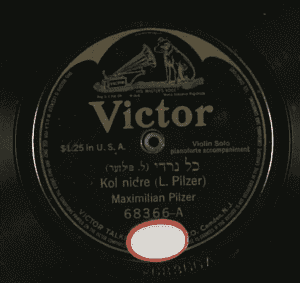

Other significant historical recordings of Rosenblatt and others can be heard on the Library of Congress National Jukebox. Three of these Kol Nidres are from Victor records (Victor Talking Machine Co.).

* A 1912 recording by violinst Maximillian Pilzer, listed in the Victor catalog as Plegaria hebraica.

* Cantor Josef Rosenblatt sings Kol Nidre in Hebrew on a 1913 record. (Its B-side is a memorial song for souls who perished in the sinking of Titanic the previous year.)

* Rosenblatt’s “Die Neuer ‘Kol Nidre'” recorded in English in 1923, with an ensemble (violin, viola, cello, flute, and organ) conducted by Victor’s musical director Nathaniel Shilkret.

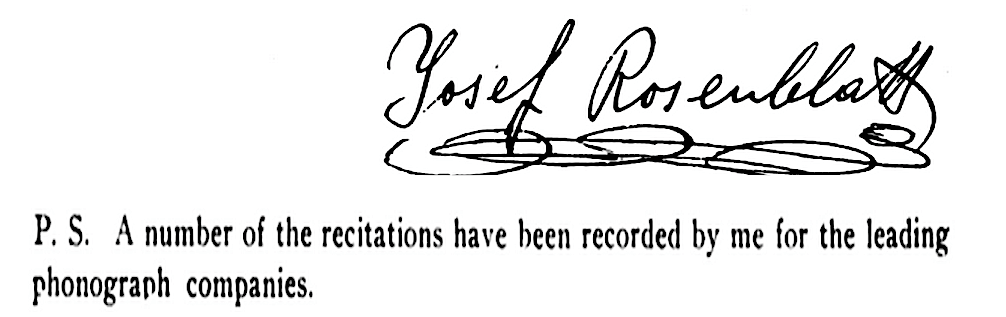

Josef “Yossele” Rosenblatt was a popular singer (“the Jewish Caruso”) and recording artist until his death in 1933, as well as the leading cantor of his era. From the foreword to his book Selected Recitatives by Cantor Yosef Rosenblatt for the Synagogue (1927):

He performed as himself in The Jazz Singer (1927). In this scene, Jolson’s title character attends a Rosenblatt concert of sacred songs, thereby preparing for his return to sing Kol Nidre in his father’s synagogue.

As Hillel Tryster pointed out, he died while in Palestine to make one of the earliest sound films produced there. (R.S.H. Tryster blog comment, Aug. 23, 2013).

Released in 1934 as The Dream of My People (Halome Ami, Palestine-American Film Co.), the movie was narrated in English by Zvee Scooler, later a familiar character actor in American movies. The National Center for Jewish Film restored this, as well as other films dealing with Kol Nidre. In the 1939-40 Yiddish film Overture to Glory (Der Vilner Shtot Khazn, aka Der Vilner Balebesl) singing star Moishe Oysher plays a cantor who becomes an opera sensation before ultimately returning to his Vilnius synagogue, where he joins the singing of Kol Nidre — and dies at its conclusion! (Watch the un-restored movie ending here.)

The NCJF also produced the DVDs Great Cantors of the Golden Age (1990), with the track “Cantor Adolph Katchko – Kol Nidre (1937)” and Great Cantors in Cinema (1993), with a selection of Rosenblatt in The Dream of My People and Oysher in Overture to Glory. These were re-released as a double DVD in 2006.

Finally, in 2007, the magazine Reform Judaism compiled a rich annotated list of “Ten Kol Nidre Tracks.” Here’s my condensation, with some amplifications and additional metadata.

Other Lewandowski recordings appear on Vorbei — Beyond Recall (BCD 16030, 2001), a CD issued by the German label Bear Family Records, describes its content as “a record of Jewish musical life in Nazi Berlin, 1933-1938.”

Ah! But here (“archived” as a .rar file), from a website in Russian (yiddishmusic.jewniverse.info), is a reproduction of the 78 Tryster inherited from his grammy’s gramophone: the B side of a 1929 Odeon recording.

Ah! But here (“archived” as a .rar file), from a website in Russian (yiddishmusic.jewniverse.info), is a reproduction of the 78 Tryster inherited from his grammy’s gramophone: the B side of a 1929 Odeon recording.

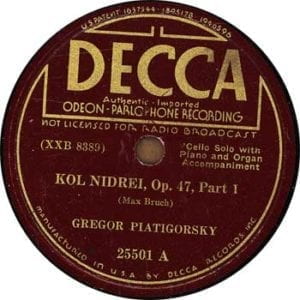

Piatigorsky and his cello can be seen playing Kol Nidre in a documentary for the Jewish Chautauqua Society, Choose Life (1976). I haven’t seen the film, but a book of the same title has this to say about it:

It is the eve of Yom Kippur, 1973, and Gregor Piatigorsky, the world-renowned cellist, is introduced by Rabbi Nussbaum and begins the Kol Nidre. Half way around the world the Arabs have launched their attack on Israel. This is the first time Piatigorsky has played in a synagogue, and significantly he is playing Kol Nidre, which Tolstoy said described the “martyrdom of a grief stricken people”. As that magnificent music is played so eloquently and heart-rending by Piatigorsky, the rabbi is giving his sermon, which that night was entitled “Choose Life,” and which he says is our prayer for peace.

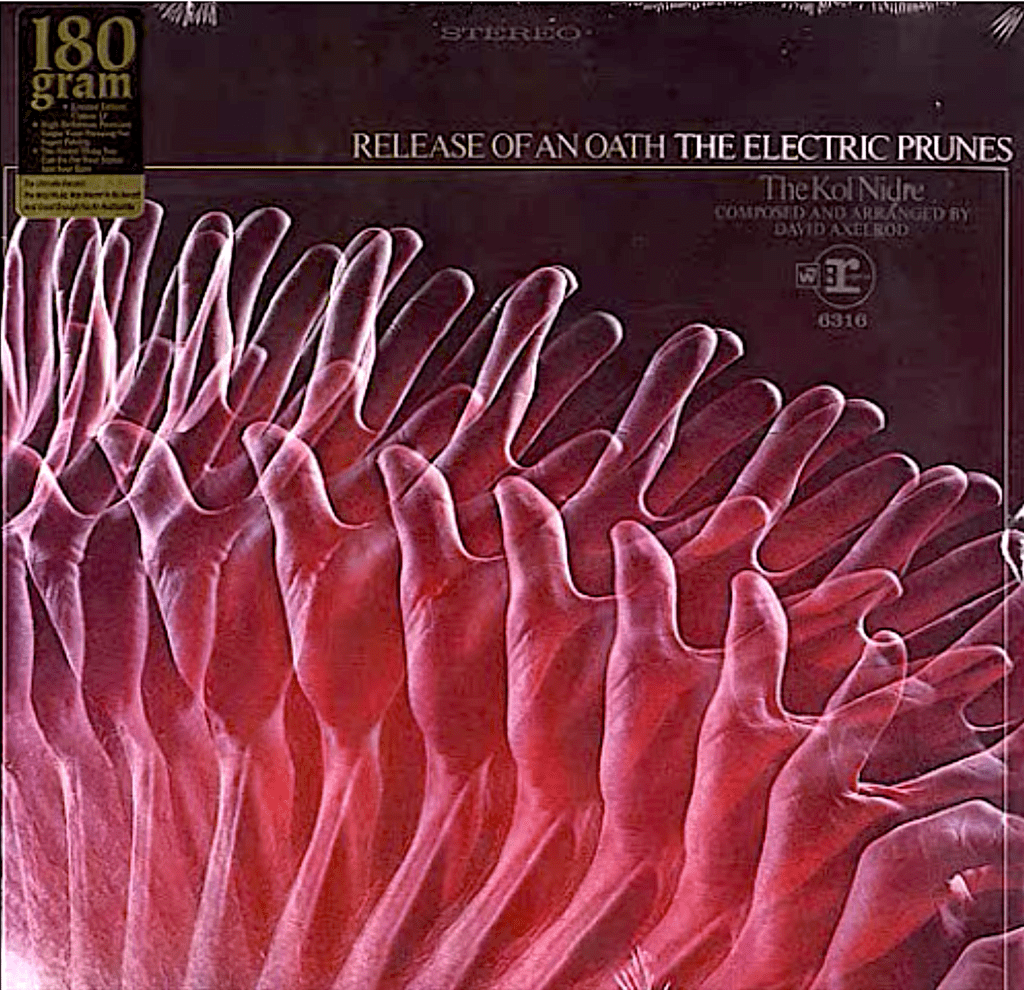

9. The Electric Prunes, LP, Release of an Oath: The Kol Nidre — A Prayer of Antiquity (Reprise, 1968). In English. Here’s the liner note to this LP, written in the spirit of the times, by someone named Jules B. Newman (about whom I can find no information, unless he was the Chicago business owner who helped raise funds to build building Congregation Rodfei Sholom).

search for a better life, been forced by powers beyond his control to foreswear the principles of his fathers and to accept the yoke of a conqueror who might vanquish his body, but not his soul. But no man of principle can live with himself having foresworn the ideals that he lives by. In yearning to free his spirit of the conqueror’s yoke, he has conjured up a psychological release that enables him to break the chains that bind him to any oath made under duress and in violation of his principles. Such a lament is the Kol Nidre – a prayer of antiquity which cleanses the spirit and enables man to start anew, with his eyes again on the stars. This, then, is the music of the Kol Nidre, which is as modern and meaningful today as when it was first written. David Axelrod has brought the music into a contemporary stance by blending the melodies of the centuries with today’s contemporary sounds. David Hassinger has taken the efforts of David Axelrod and, with his provocative talents, has in turn blended them into this artful presentation by The Electric Prunes.

search for a better life, been forced by powers beyond his control to foreswear the principles of his fathers and to accept the yoke of a conqueror who might vanquish his body, but not his soul. But no man of principle can live with himself having foresworn the ideals that he lives by. In yearning to free his spirit of the conqueror’s yoke, he has conjured up a psychological release that enables him to break the chains that bind him to any oath made under duress and in violation of his principles. Such a lament is the Kol Nidre – a prayer of antiquity which cleanses the spirit and enables man to start anew, with his eyes again on the stars. This, then, is the music of the Kol Nidre, which is as modern and meaningful today as when it was first written. David Axelrod has brought the music into a contemporary stance by blending the melodies of the centuries with today’s contemporary sounds. David Hassinger has taken the efforts of David Axelrod and, with his provocative talents, has in turn blended them into this artful presentation by The Electric Prunes.This media archaeology about the presence of Kol Nidre ends with another surprising turn — in an Afghanistan war zone in 2009. The Jolliet sitar version of the incantation led the Canadian Broadcast Corporation to produce this radio documentary — The Kol Nidre in Kabul — for its series Outfront. Listen here.

Returning to the beginning, here’s “All Vows” (2016) as a cello solo.

Selah!