A program entitled “Orphan Films of Outer Space,” is part of the World of Knowledge: International Film Festival of Popular Science and Educational Films, which runs December 1-6, at the Lenfilm Cinema Center in St. Petersburg, Russia. On Sunday, December 5, 2021, I will introduce the films (via Zoom) to the viewers in the New Holland Pavilion. After the terrestrial projection of a 16mm print and four digital videos, filmmaker Jeanne Liotta and I will participate in a Q&A.

The line-up:

• Passage de Vénus (Jules Janssen and Francisco Antônio de Almeida, 1874) 5″

• The Transit of Venus (David P. Todd, 1882) 15″

• Solar Eclipse (Nevil Maskelyne, 1900) 1′

• The Comet (Edison, 1910) 2′ with premiere of a new music by Andrew Goehring (NYU Screen Scoring ) [now streaming; it’s delightful]

• Meteorites (Pavel Klushantsev, 1947) 10′

• Beyond the Moon (R. E. Barnes, ca. 1961) 11′

• Project Apollo (Ed Emshwiller, USIA, 1968) 30′

+ a non-orphan film, Observando el Cielo (Jeanne Liotta, 2007) 19′

The festival notes its theme this year is space, observing the 60th anniversary of Yuri Gargarin’s flight, the first into space by a human being. In February 2021 Walter Forsberg and I did a similar event for the space exploration conference known as Roger That! Here’s a link to the launch of a series of blog posts about ten films that appeared on the DVD set Orphans in Space: Forgotten Films from the Final Frontier. That project included two productions from the Soviet Union, so a Russian festival on popular science films is a fitting next step.

Here’s an illustrated program of precinema artifacts and early cinema on the theme that others have published online. Total running time: 80 seconds.

Program notes by Dan Streible

Passage de Vénus (Jules Janssen and Francisco Antônio de Almeida, 1874) 5 seconds.

This 2012 YouTube post by “magical media museum” is the oldest one on the web in 2021. Where did it originate? with a Dutch animator’s web version in 2004? or a French film version of Janssen’s disc in 1950?

A noted French astronomer and a Brazilian engineer invented a photographic device to record a set of images of the planet Venus passing before the Sun, as seen they observed it from Japan, December 9, 1874. But this video reanimation of the daguerreotypes made using Jules Janssen’s “revolver photographique” is not what if first seems. In fact, the above video is found on more than 50 YouTube channels, but none say where it came from. Who made it? when and how? The above is a 2012 posting by the Media Magic Museum channel, the earliest YouTube post, but certainly not the source of creation.

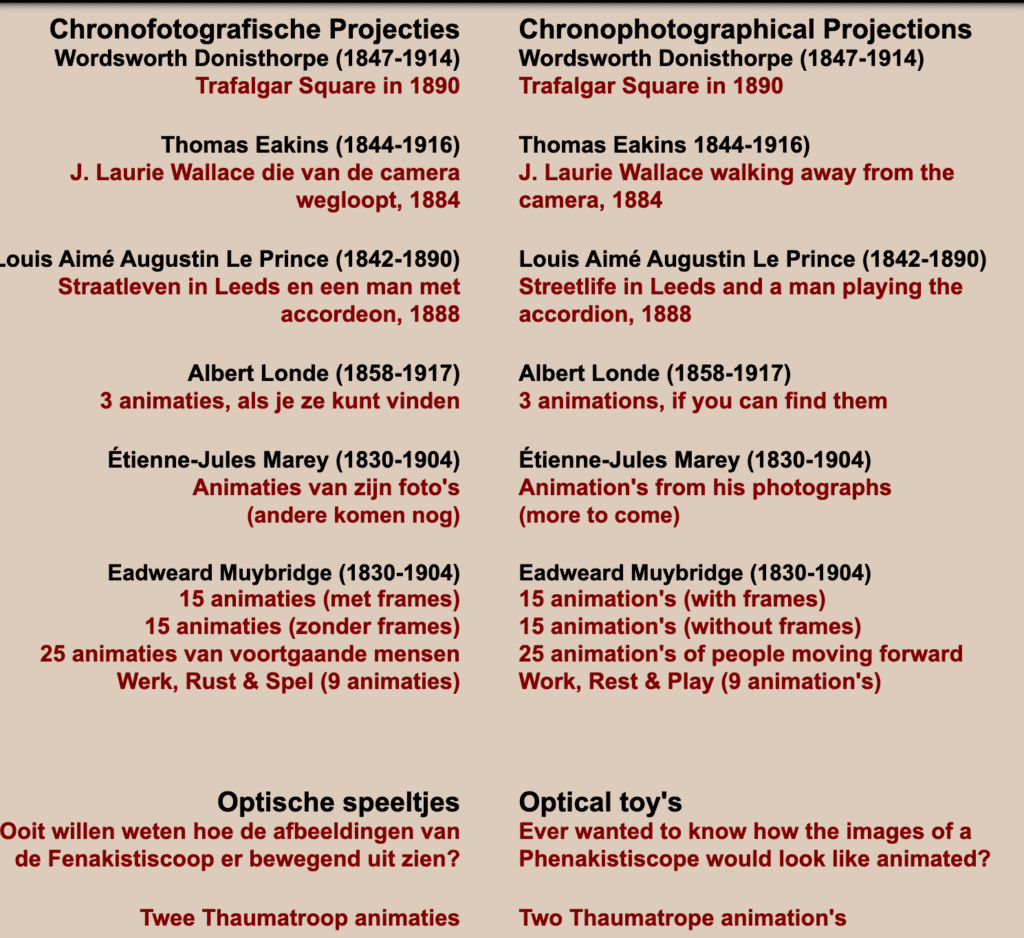

In her 2012 book The Astronomer Jules Janssen, Françoise Launay of l’Observatoire de Paris, cites one Charl Lucassen posting a video animation (ca. 2004) of the 1874 images to his personal website, now defunct. Lucassen, an independent scholar and animator based in Leiden, is praised in other precinema web resources and in biographies of Eadweard Muybridge by Rebecca Solnit and Stephen Herbert. Luke McKernan‘s valuable 2008 report, “Lost Sites,” for The Bioscope ends with: “the website whose passing I most regret, Charl Lucassen’s beautiful Anima site on chronophotography and other optical delights, once one of the genuine treasures of the Web, is nowhere to be found at all. Such a loss.” The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine reports “404 — Nothing found” at the published URL, but a similar address for Anima retains 11 screenshots taken during 1999 through 2003. [Update: even this was deleted in 2022.] No images and certainly no animations are saved, but the remnants of Lucassen’s texts document which “Chronophotographical Projections” once played the turn-of-the-century Internet.

This WayBack Machine screenshot is from October 18, 1999. No mention of Jules Janssen or the Passage de Vénus.

And there was no YouTube in the wide world when Anima went dark in 2004. We can only presume the 5-second video that dozens of others have posted to YouTube between 2012 and four hours ago [!] is a clone of Charl Lucassen’s upload.

However, a half century before Lucassen made his Janssen video, the 1874 Passage de Vénus images were reanimated on film. Another Launay footnote tell us in 1950, Joseph Leclerc, founder of the film archive of Société astronomique de France, rephotographed the tiny images on one of Janssen’s discs using a motion-picture film camera. Leclerc himself wrote about it in “Jules Janssen et le cinématographe,” l’Astronomie, 69 (1955): 388–91.

The punchline is that Launay established in 2005 that the images we see reanimated are from a “practice plate” Janssen made when photographing simulations of the transit of Venus before the celestial event. In 1950, Leclerc mistakenly believed these were from the “revolver photographique” daguerreotype disc that Janssen and engineer Francisco Almeida made in Japan. Janssen did successfully make the 1874 photographs, but they do not survive.

[Update 2022: The happier punchline is that publication of this post led to this email.]

Date: Oct 19, 2022 at 4:10 PM

Subject: Source of Passage de Venus (1874)

I read your article, Capturing Venus in Motion and Filming an Eclipse in the 19th Century, and was also shocked to find very little information on the whereabouts of the actual plates, or where that video came from.

I got a hold of Launay’s book, The Astronomer Jules Janssen, and one of the citations led me to this documentary, which shows the clip in a much higher quality. I’ve inverted it and uploaded it to youtube here. The documentary has a semi-transparent logo that I’ve attempted to color correct out. The Youtube clips don’t seem to have any traces of it. But I believe the logo was added digitally later, as it’s possible to order a version through the site with no logo.

I’m not sure I could have found this without your article, so thanks!

Will May

Et voilà!

Merci, M. May.

The video is from the website of France’s Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS). This well-crafted 35mm educational film has the English screen title The Origins of Scientific Cinematography.

“© IWF / CNRS / Luce / Virgilio Tosi – 1989.” It runs 52 minutes. After publication of the post I had found Les Origines du cinéma scientifique through other means, but did not update this.

The Transit of Venus (David Peck Todd, 1882) 15 seconds.

An American astronomer made 141 glass-plate photographs of the phenomenon as seen from California in 1882. The plates were rediscovered at the Lick Observatory and reanimated in 2003 by William Sheehan and Anthony Misch. The 15 seconds of video represents more than 4 hours of the complete transit. Here is a 2012 copy from Sze-leung Cheung.

See Sheehan and Misch, “A Movie of the 1882 Transit of Venus Assembled from Plates Taken at Lick Observatory by David P. Todd,” Journal of Astronomical Data (Nov. 2004) and”A Remarkable Series of Plates of the 1882 Transit of Venus,” (Dec. 2004).

Solar Eclipse (Nevil Maskelyne, 1900) 375 frames of 35mm film, 1 min.

On May 28, 1900, a British amateur filmmaker recorded a total eclipse of the sun in Wadesboro, North Carolina (U.S.) using a custom-rigged motion-picture camera. When the Royal Astronomical Society rediscovered Nevil Maskelyne’s film in its archive, the BFI National Archive restored it in 4k in 2019.

As a cinematic experience, this little film of a big thing still has oomph, even in this 720p video stream. The 4K file is available to license from the BFI.

Two lost films:

[Eclipse viewed from Viziadrug, India] (Lord Graham, 1898) Eclipse Expedition, Royal Astronomical Association.

[Eclipse viewed from Buxar, India] (Gertrude Bacon, 1898) Eclipse Committee, British Astronomical Association

Three 35mm cameras in India recorded the January 22, 1898 solar eclipse. A large professional scientific team from the Royal Astronomical Association, led by Norman Lockyer, took a battery of cameras and instruments, including motion picture gear. In the book Recent and Coming Eclipses (1900) he refers to two “kinematograph” machines, one to film the eclipse, the other its shadow. Each had its own crew. Lockyer reported that 8,000 frames were exposed, but a crack in the wooden camera box allowed too much light in, fogging the images beyond any use. The operator he identified only as the Marquis of Graham. An elusive figure, apparently a navy man.

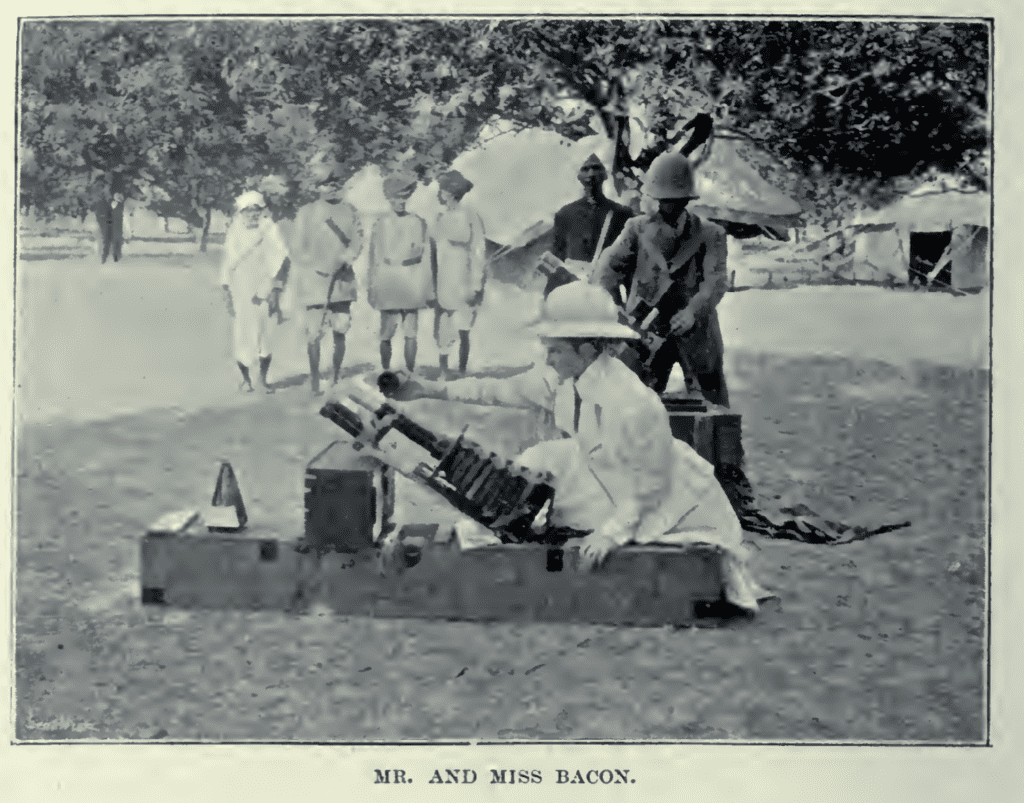

Meanwhile, for the amateurs in the British Astronomical Association, Gertrude Bacon, her brother Fred, and father John M. Bacon reported their film of the eclipse was successfully recorded using an “animatograph.” Some sources mistakenly say the noted magician Nevil Maskelyne was the cinematographer, but he was not present. However, it was Maskelyne’s camera and film stock the Bacons used. The name Animatograph specifies the invention of Robert W. Paul, who indeed worked with Maskelyne and purchased the rights to his adaptations of the camera.

The expedition’s published report said: “The heaviest and most important instrument was undoubtedly the animatograph telescope, specially designed for the expedition by Mr. Nevil Maskelyne. As a piece of delicate and complex mechanism this apparatus demanded much care and manipulation, and a certain period of each day was set apart for requisite practice. At intervals, too, during the voyage, a practical use was made of its capabilities. A number of spare films had been supplied by Mr. Maskelyne, in addition to one of special length for the eclipse; and with the consent and ready co-operation of our genial captain several photographs of animated scenes on board ship were secured.” (33).

Newspapers noted the presence of the special cameras in Buxar and sometimes reported they had captured the solar eclipse on films, with their owner Maskelyne about to show them publicly in London at his popular Egyptian Hall. (Edinburg Review, April 1899, 316)

However, when the ship carrying the Bacons’ films and Maskelyne’s camera arrived in England, all objects arrived safely — except the can containing the eclipse footage. In public talks about the India expedition, John M. Bacon showed photographs taken by Gertrude and Fred, but told of the disappointment finding the eclipse film had been lost or stolen.

But the Bacons persisted. When Maskelyne filmed the 1900 solar eclipse in North Carolina, they accompanied him. Gertrude Bacon “worked successfully four cameras simultaneously” with “special light-gathering lenses” her father told the local press. (“The Sun Eclipsed,” Messenger and Intelligencer, [Wadesboro, NC], May 31, 1900.)

A year later another woman appeared on the eclipse-filming scene. A syndicated Reuter’s news item noted in passing that a British expedition viewed the solar eclipse on the island of Mauritius (then a British colony), saying almost cryptically “… and Mrs. Ireland drove the Maskelyne kinematograph.” (“The Eclipse of the Sun,” London Observer, May 19, 1901). A British Astronomical Association report connected the moment to the previous mishaps with eclipse footage. Members discussed the Mauritius observations at a meeting and reported they “might hope at a future meeting to see a kinematographic view of the eclipse, as the [Reuters] telegrams went on to show that a successful kinematographic film was taken by Mrs. Ireland, with Mr. Maskelyne’s famous instrument.” The minutes concluded by saying one member “hoped that no contretemps would occur on this occasion as happened in India, when the film was lost [true], and in America, when the kinematograph was lost” [not true]. (Journal of the BAA, vol. 11, no. 8, May 29, 1901, p. 309.)

Who was this camera “driver” and eclipse follower, “Mrs. Ireland”? Perhaps the Mrs Ireland who the Astronomical and Physical Society of Toronto elected to its membership in 1896? Perhaps not.

Still another female member of the society of eclipse-chasing science cinematographers reported from Mauritius, one with a consequential career in astronomy. Annie Scott Dill Maunder (1868-1947) was a mathematician married to astronomer Edward Walter Maunder (1851-1928). Their research collaborations from 1890 onward included the photography of sun spots. He founded the BAA for amateurs, particularly women excluded from professional ranks, and with Annie edited its journal. Both published scientific accounts of their 1901 eclipse observations. She gives us a clue as to who “Mrs. Ireland” was, while also revealing what became of the film attributed to her.

As “(Mrs.) A.S.D. Maunder,” she read a paper at a Royal Astronomical Society meeting in 1901. The published version details the scientific and photographic instruments the Royal Observatory crew took to Mauritius. “Mr. Nevil Maskelyne also lent me his kinematograph,” she added. “Management of these instruments during the eclipse was very kindly undertaken by several friends.” She identifies among the personnel “Mr. G. H. Ireland: Kinematograph.” A Mrs. Ireland is not mentioned. (Mister was a member of the Colonial Service on the island.)

“The kinematograph gave no result,” she notes, “the film tearing across before totality was reached.”

Addendum (celestial photography as colonialist practice)

Photograph from the British Empire & Commonwealth Collection, Bristol Archives, Bristol Museums, UK.

Who was Mrs. Ireland, driver of the Maskelyne kinematograph in 1901? This is (apparently) not a photograph of her. But the caption — “G H Ireland’s bungalow in Mauritius, c.1902” — conjures up an idea of what the white Europeans from the Royal Observatory might have experienced when venturing to that African island in the Indian Ocean. A privileged, protected, parasol-and-plantation idyll from which they could cast their gaze and cameras upon the celestial bodies far from Earth.

Sources:

Françoise Launay and Peter D. Hingley, “Jules Janssen’s ‘Revolver Photographique’ and Its British Derivative, ‘The Janssen Slide,'” Journal for the History of Astronomy, 36, no. 1 (2005): 57-70.

Sir Norman Lockyer, Recent and Coming Eclipses, 2nd ed. (1900).

Sir Norman Lockyer, “Total Eclipse of the Sun, January 22, 1898, Preliminary Account,” Report on the Solar Eclipse Expedition to Viziadrug (1899).

A. S. D. Maunder, “Preliminary Note on Observations of the Total Solar Eclipse of 1901 May 18, made at Pamplemousses, Mauritius,” read at a joint meeting of the Royal and Royal Astronomical Societies, Oct. 31, 1901, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, April 4, 1902.

E. Walter Maunder, ed. The Indian Eclipse, 1898: Report of the Expeditions Organized by the British Astronomical Association to Observe the Total Solar Eclipse of 1898 January 22 (1899). 172 pp.

Jessica Ratcliff, The Transit of Venus Enterprise in Victorian Britain (U of Pittsburgh Press, 2016).

Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, “The Social Event of the Season: Solar Eclipse Expeditions and Victorian Culture,” Isis 84, no. 2 (1993): 252–77.

George Strahan, The Total Solar Eclipse, January 22nd, 1898 (Dehra Dun, India: Survey of India, 1898). 28 pp.

Bonus: If you’ve made it this far, treat yourself to this short short with

The Comet (Edison, 1910) 2 min.

The New York theatrical showcase Ziegfeld Follies of 1910 commissioned the Edison film studio to create this curiosity. Projected only for the theater production, it shows the faces of stage stars Anna Held and Harry Watson sticking out from a canvas painted to resemble a comet. Halley’s comet was in the news due to its vivid appearance in the days before the show’s debut. A song written for the occasion, “The Comet and the Earth,” was sung live as the film appeared behind the live actors.

Preserved in 35mm by the U.S. Library of Congress.