Orphans in Space: Forgotten Films from the Final Frontier

special edition for Roger That! 2021

Project Apollo (Ed Emshwiller, USIA, 1968)

Project Apollo (Ed Emshwiller, USIA, 1968)

30 min., color, sound.

Sources: Museum of Modern Art and Anthology Film Archives

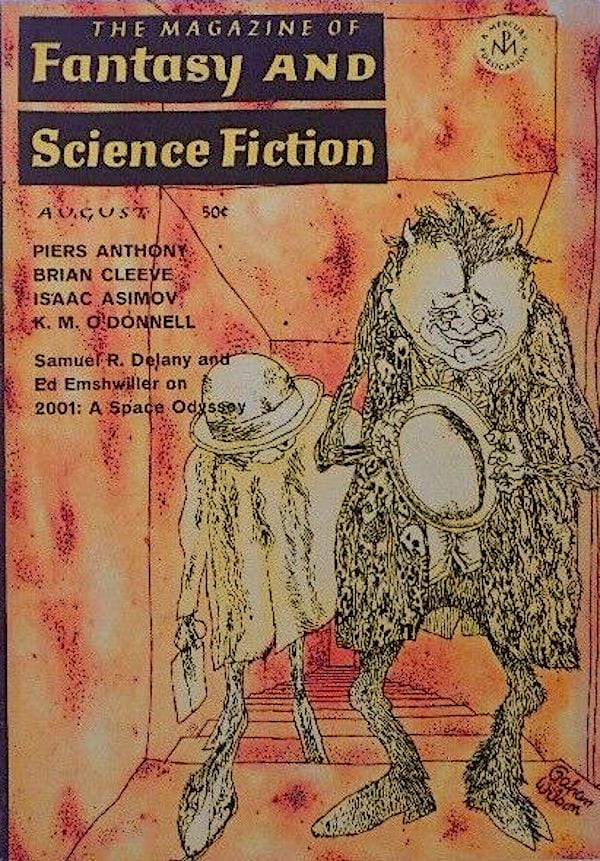

Filmmaker Ed Emshwiller (1925-1990) was an accomplished visual artist, working in media ranging from abstract painting to 3-D computer animation. In the 1950s, “Emsh” first became known for his pulp-realist and fantastical cover art for science fiction magazines and novels. By the mid-1960s, he had made his mark in avant-garde film and video. However, his American followers were unable (with rare exceptions) to see his masterful and unconventional documentary Project Apollo, made for the United States Information Agency in 1968. The USIA’s Motion Picture and Television Service budget appropriated $77,008 for the production. The contract dated October 4, 1967, went to “E-Spec Films, Inc. (Edmund Emshwiller).” Using no narration, dialogue, or interviews, the movies pays quiet tribute to the many unnamed NASA employees seen at work in preparation for the Apollo 9 mission.

USIA productions were made to promote American interests to viewers in other countries; until 1990, federal law made it illegal (with some exceptions) to show such ideologically conceived material inside U.S. borders. Hence, one can find libraries in South Africa and Canada, for example, holding copies of Project Apollo, but none in the United States.

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration holds the records of the USIA (Record Group 306), including much of its moving image output. The USIA often distributed films that had been produced for other purposes, translating them into dozens of languages. These included works as diverse as Emile de Antonio’s documentary about postwar American art, Painters Painting (1972), and Willard Van Dyke’s obscure New York University (1952), an orientation film commissioned by NYU’s alumni association. The agency also originated hundreds of films, sometimes hiring newsreel crews, other times new creative talent. As USIA Motion Picture Service head from 1962 to 1967, George Stevens Jr. especially recruited the latter. Emshwiller began as a USIA cinematographer in 1963, helping to record the March on Washington for director James Blue’s USIA documentary The March.

With its modernist minimalist score, cool technical precision, and formalist design, Project Apollo was distinctive from most USIA films (of which there were thousands throughout the Cold War).

Its atmospheric and stylistic correspondence to parts of 2001: A Space Odyssey is apparent to the few viewers who have previously seen both 1968 productions.

In his review of Kubrick’s cinematic landmark, Emshwiller revealed the point at which the two directors intersected.

In his review of Kubrick’s cinematic landmark, Emshwiller revealed the point at which the two directors intersected.

[T]he second sequence in the picture is a beautifully choreographed passage with just a space ship, a space station, the earth, and the stars. There is no “action” except the docking of the ship to the station. The pace is unhurried, as is true of much of the picture, yet this sequence, with its sweeping, turning movements, makes great kinesthetic use of the big screen in an almost abstract sense, a joy of pure movement. . . .

I realize the film is stylized, but the manner of conveying “human” touches, even when ironic, seems studied and unreal. I’ve just spent the past six months making an impressionistic film of Project Apollo and have encountered a lot of bureaucrats and spaceman types. Some I liked and some I didn’t, but in all cases they were somehow more textured than their counterparts in 2001… .

At one point early in making the film, Kubrick asked me if I would assist in designing [the final sequences]. I read the script he and Arthur Clarke had written. The problem obviously was to create an overwhelming alien world experience. For various reasons I did not become involved in the project, but I was intensely curious to know how he would solve the problem. As it turned out he did it beautifully, with apparent economy of means and with great visceral impact. In this sequence his use of semi-abstractions and image modification (solarization, color replacement, etc.) brings to the big screen techniques which once seemed the province of the avant-garde or experimentalists.

. . . The film had, for me, a satisfying amount of what [writer and SF historian] Sam Moskowitz calls a “sense of wonder,” and a feeling which some good science fiction has for the sensual and mysterious regions surrounding our feeling about machines, time and space.

—

—

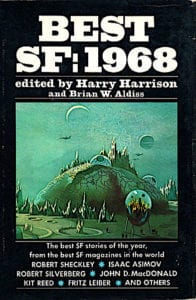

Source: Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (August 1968). Reprinted in The Year’s Best Science Fiction No. 2 (London: Sphere, 1969) and Best SF: 1968 (New York: Putnam, 1969), both edited by Harry Harrison and Brian W. Aldiss.

Also transcribed at The Kubrick Site, www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk.

—

Dan Streible first saw this film at the first Orphan Film Symposium in 1999, when Robert Haller of Anthology Film Archives presented a color-corrected video version derived from Emshwiller’s personal print. Access to and knowledge of USIA films began to expand in the 1990s after Congress made it legal to access them in the United States. The federal ban on showing state-funded propaganda to its own citizens was undone in 1990 when 22 U.S. Code § 1461 instructed agencies and the National Archive to “make available, in the United States, motion pictures, films, video, audio, and other materials disseminated abroad. . . .”

Preservation note

The National Archives reports no holdings for Project Apollo in its USIA collection. The source for this DVD was a 16mm print from the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA’s Emshwiller holdings include material about his video and computer graphic work at television station WNET in New York (1972-79). Colorlab made a 1080p HD video transfer, performing color correction. This was done with the approval of Carol Emshwiller for the NYU Orphan Film Symposium’s DVD Orphans in Space, produced by Walter Forsberg, Alice Moscoso, and Jonah Volk.