A third post about the wonderful little big-format film of 1897 called The Haverstraw Tunnel, presented below in a restored form, online for the first time. We must thank the British Film Institute and BFI National Archive for the work (thanks, Bryony Dixon) and the access (thanks, Espen Bale).

To appreciate the historical significance of The Haverstraw Tunnel, see the February 29, 2020 post “68mm 8k Phantoms” (how the film caused a sensation in 1897 and generated a name for a genre, the phantom ride — but was not on the web or DVD) and the March 5 post for which the Library of Congress shared (thanks, Mike Mashon) a digital copy of its 16mm film copy in the Paper Print Collection. There I describe the elements housed at the BFI that made possible the restored Haverstraw film.

Cutting to the chase, here’s the MP4 access file from BFI Archive Sales (with some uploading compression of course). The surviving pieces of 68mm were in rough shape, so what we see 123 years later is not as spectacular as it might be — at least not without benefit of 4k projection. But the image resolution is strikingly higher than that of the LOC paper print. archive.org/details/haverstraw_tunnel

[archiveorg haverstraw_tunnel width=640 height=480 frameborder=0 webkitallowfullscreen=true mozallowfullscreen=true]

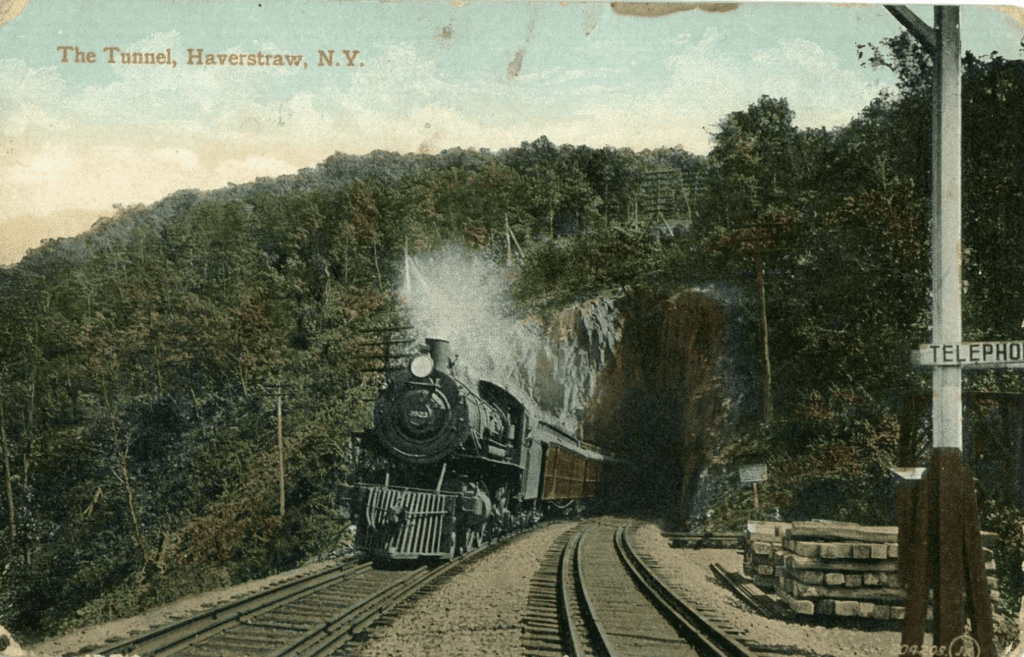

The American Mutoscope Company film may have been lengthier than what survives here. But the key moment of the train entering and exiting the tunnel remains intact.

One imperfection could be misleading. Upon entering the tunnel, the image does not turn completely dark. For five seconds we see small grayish rectangles, which disappear when the light from the tunnel exit begins to appear. These are remnants of the mechanical imperfection visible in some 68mm films, defects peculiar to the “mutograph” camera’s high-speed (30 frames per second or more) feed mechanism, which punched sprocket holes into the raw film stock as it passed through the gate. Similar light artifacts can be seen in, for example, two of Eye Filmmuseum’s restorations: Kerstman en fee [Santa Claus and Fairy] and Coronation of Queen Wilhelmina of Holland at Amsterdam (both British M&B, 1898). Reports of Biograph viewings in 1897-98 do not mention this. They only marvel at the clarity of the image.

A Los Angeles Times report of December 5, 1897, for example, is effusive, noting no imperfections. Although the eighth of ten animated pictures on the American Biograph program at the Orpheum theater, the phantom ride stood out, even alongside reverse-motion and hand-colored pieces. “Probably the greatest of all these is the picture of the Haverstraw Tunnel, taken from the front of a train as it approaches, enters, and exits the tunnel. This scene is said to be beyond all question the most vivid and sensational ever produced by any moving-picture machine. It is said to be practically a realization of a ride upon a cow-catcher of an engine on the West Shore express through the Haverstraw Tunnel.”

Below is a rudimentary desktop comparison of the two versions. I slowed the LOC file but didn’t quite get the two synchronized. The BFI file runs exactly 1 minute; the LOC file 39 seconds (a 24fps transfer of the 16mm film). At 27 feet in length, this 16mm print transferred at 18fps would also run exactly 1 minute. The paper print contains frames at the end not seen in the British copy.

[archiveorg haverstraw-tunnel-comparison width=640 height=480 frameborder=0 webkitallowfullscreen=true mozallowfullscreen=true]The higher resolution of the file derived from BFI’s 68mm materials is obvious. Superior detail, clearer contrast. The paper print also crops edges of the image on all sides, which is especially noticeable at the top.

The final frames make the comparison most dramatic, as the Hudson Highland mountain — High Tor — that dominates the view upon exiting the tunnel is nearly invisible against the dull gray sky seen in the paper print. (The Hudson River and its Haverstraw Bay are off-screen to the right, and in the distant background. The train was tracking from south to north, the tunnel being south of the town.)

The town of Haverstraw is in Rockland County, about 35 miles north of Manhattan, on the west side of the Hudson River. Notably, the river is at its widest (nearly three and half miles) at Haverstraw Bay.

Other views:

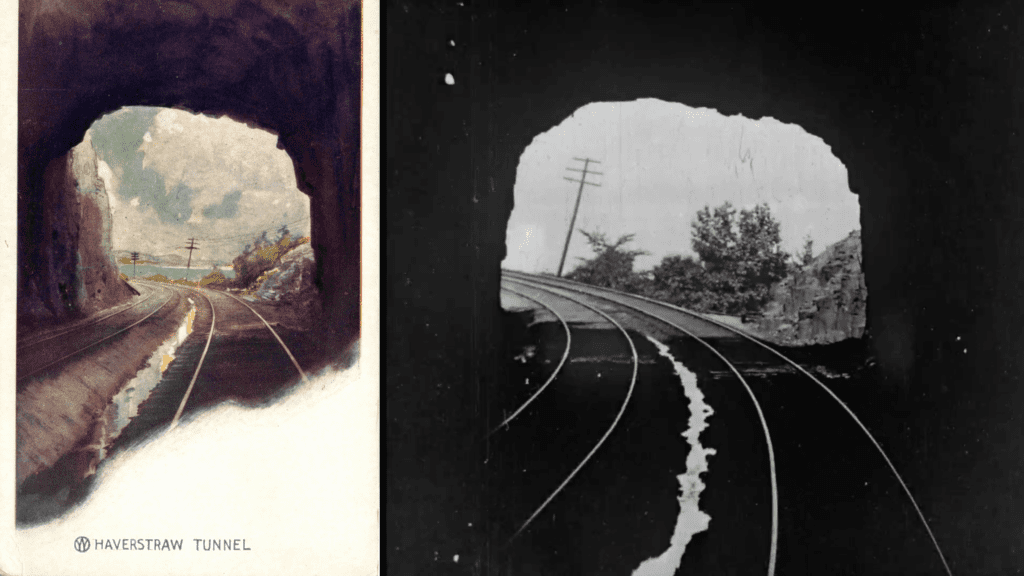

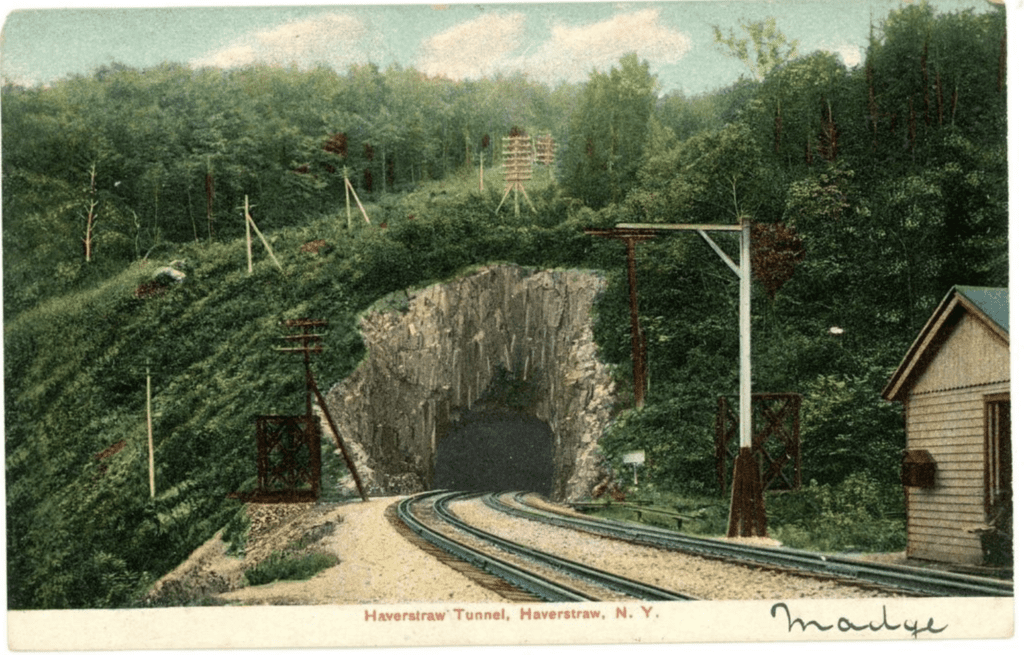

After studying the motion picture of the train trip through the tunnel (and let it be said that early cinema produced many train-in-tunnel films), I examined postcard images of Haverstraw made in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With some delight we can see that the Mutoscope scene was followed by other images that derived from the movie.

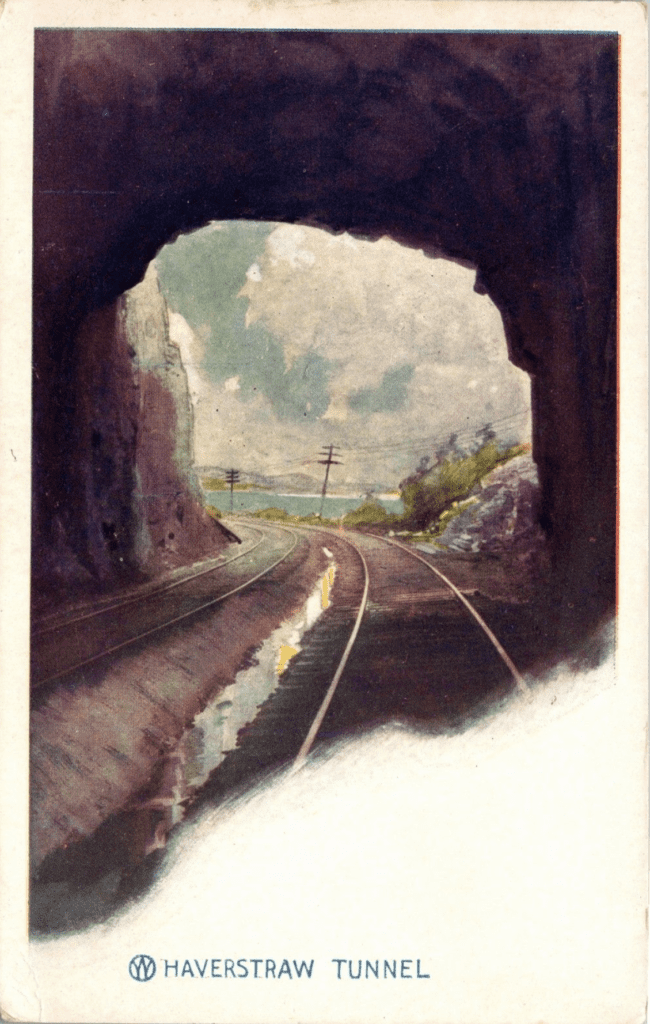

The railroad company distributed a postcard (circa 1905-06) that certainly seems to be derived from a frame of the celebrated film.

The circulation of frame enlargements in print was not unknown but for American Mutoscope and Biograph, which created thousands of 4×6-inch mutoscope cards, still images would have been more readily available. A similar composition also appears as one of the key frames for production no. 301 in the Biograph Photo Catalog, vol. 1.

The circulation of frame enlargements in print was not unknown but for American Mutoscope and Biograph, which created thousands of 4×6-inch mutoscope cards, still images would have been more readily available. A similar composition also appears as one of the key frames for production no. 301 in the Biograph Photo Catalog, vol. 1.

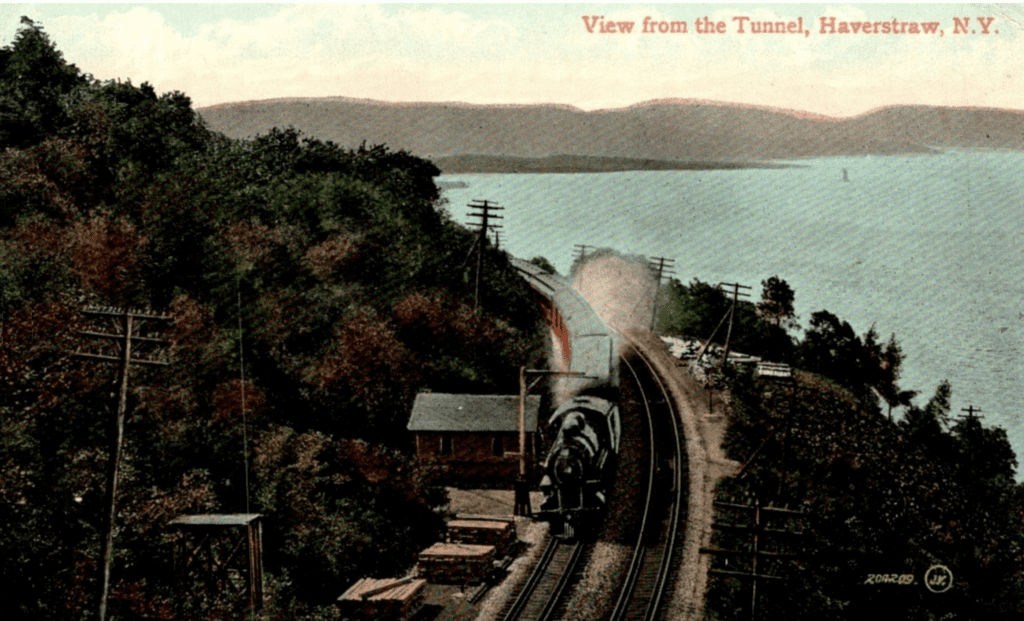

The postcard image had an earlier source. In 1898, the West Shore Railroad company placed five commissioned paintings (or prints) in sites around New York, each showing “picturesque localities in the Catskill mountains,” including one entitled “The Entrance to the Haverstraw Tunnel.” The image below may well be a reproduction of another painting in the series, “Haverstraw Bay and Environments,” which “looks from a point just without Haverstraw tunnel” over the Hudson to “the purple mantled mountains” in the distance. (See “Scenery Along the Hudson,” Omaha Daily Bee, Oct. 6, 1898.)

Early cinema had extensive commercial and intermedial relationships with the railroad industry (see Lynne Kirby’s book Parallel Tracks). Paul Spehr’s biography of W. K. L. Dickson documents how New York Central Railroad commissioned, cross-promoted, and exhibited the American Mutoscope Company’s first sensation, The Empire State Express (1896). It’s logical that competitor West Shore Railroad would have capitalized on the success of its Haverstraw film.

Another publication appeared at the time, Summer Homes and Tours on the Line of the Picturesque West-Shore Railroad, a 300-page guidebook issued annually from 1895 to 1900.

The 1896 edition (online here) waxed literally poetic about the view exiting the tunnel on a passenger express train. Following a poem by Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Hudson,” the book’s touristic narrative offered this description:

Suddenly we plunge into a tunnel and in a moment emerge, into the sunlight and our eyes rest on one of the most magnificent scenes the imagination can conceive. The quiet landscapes and low levels through which we have passed are changed for lofty mountains on the one side and the broad-sweeping waters of the Hudson River on the other. The track is clinging to the side of the High Torn [Tor] Mountain and a hundred feet below flows the majestic Hudson, widening out into what is known as Haverstraw bay. Our first exclamation was, “Oliver Wendell Holmes is right.” The Rhine, the Rhone, the Avon, are not to be compared with this. (23)

The 1898 edition, according to the Brooklyn Standard Union, featured a new cover, a striking lithograph of “a view down the Hudson from the north portal of the Haverstraw tunnel” (June 15, 1898). The lithograph might well be the same image described in the Omaha newspaper, likely reproduced in the postcard.

Until confirming visible evidence of the 1898 West Shore travel guide is found, we have the 1896 version to examine. Does it foresee the cinematographic rendering of 1897?

— Dan Streible

New York University