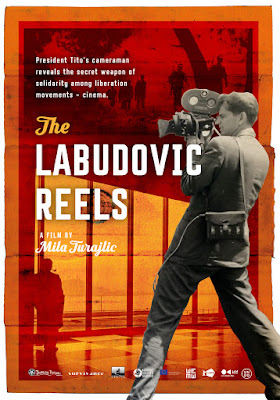

Filmmaker (and scholar) Mila Turajlic is on a roll. Her 2017 documentary, The Other Side of Everything, has been garnering wide praise since its debut at the Toronto International Film Festival and acclaim at the International Documentary Filmfestival in Amsterdam. (Or as Variety, which always boils the takeaway down to telegraphic declarations, put it: “Serbian Doc Wins Big at IDFA.”) Meanwhile Turajlic is making another feature-length documentary about the career of Stevan Labudovic, succinctly identified as “Tito’s cameraman.” Labudovic, who died in November 2017, accompanied the president of Yugoslavia on his world tours after Tito co-led the establishment of the international Non-Aligned Movement in 1956. Turajlic befriended the veteran fellow filmmaker and worked with him on the forthcoming project for several years.

On April 13, the 2018 Orphan Film Symposium in New York gets the privilege of having Mila Turajlic share a large sampling of archival newsfilm and documentaries made by Labudović and others in the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Little of this footage has been circulated in the last half century. Her presentation of a small sampling of it at the Cinémathèque française “Orphelins de Paris” portion of last year’s Toute la mémoire du monde International Festival of Film Restoration, prompted calls for more. Turajlic’s Orphan Film Symposium screening (8pm, Museum of the Moving Image, Friday, April 13, 2018) will provide a more in-depth look at films shot by Labudović and others.

A sample of the titles, dates, and points of origin indicates what an intriguing program it will be: Ho Chi Minh: A Friend Has Arrived (1957); Djazairouna: Our Algeria (1960) made for screening at the General Assembly of the United Nations; Venceremos: We Will Win (1968), the first documentary about Mozambique’s fight against colonial rule; and Blood and Tears (1971), on the Palestine liberation movement.

Based in both her hometown of Belgrade and Paris, Mila Turajlic studied political science at the London School of Economics, filmmaking at the French state film school La Fémis, and cinema studies at the University of Westminster, from which she received a PhD. Her breakthrough film was Cinema Komunisto (2010), documenting the history of Yugoslavia’s film industry. (Her own website is www.dissimila.rs.)

Here’s the filmmaker/scholar’s description of what we will see at “Orphans 11” and why it matters.

Films by the cameramen of the Yugoslav newsreels for the liberation movements of Algeria, Angola, and Mozambique remain an unwritten chapter in the story of Yugoslavia’s role in the non-aligned world. Sent on missions by President Tito, and supported by Yugoslav embassies and news correspondents in Africa and Asia, the cameramen established close relationships with anticolonial movement leaders. The state archives of the former Yugoslavia reveal how cinema played a central role in diplomacy, but also its value in the information battle playing out in the United Nations and the court of world opinion.

As a result of this period of transnational solidarity, the Non-Aligned collection of the Yugoslav Newsreels is an unexplored trove of documentation of Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN), Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), and the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). It also holds newsreels made for newly independent countries including Mali, Chad, and Guinea Bissau, as support for the establishment of national film centers.Stevan Labudović’s life and films offer a window into the political and diplomatic role played by cinema in this period of decolonialisation. As Tito’s cameraman, he followed the president on a series of historic voyages in the mid-1950s. Travelling as far afield as India, Indonesia, Burma, Ceylon, Ethiopia, Sudan, Ghana, Togo, and Mali, Labudović made films documenting these newly-liberated countries. As the Non-Aligned Movement was forged, its support for countries fighting against colonialism became more vocal. In 1959 Tito sent Labudović to film the FLN and to counter official French propaganda about ‘events’ taking place in Algeria. For three years Labudović shot more than 50 hours (18 kilometers) of film, becoming the cinematic eye of the Algerian war. His diaries reveal how strategically crafted his films were.

Seel also Mila Turajlić, “Re-aligning Yugoslavia: The Construction of Alterity in the Yugoslav Newsreels,” On_Culture 4 (2017): www.on-culture.org/journal/issue-4/turajilic-re-aligning-yugoslavia.

Turajlic’s trailer for her doc-in-progress begins with Leonard Cohen’s 1969 recording “The Partisan,” his version of a 1943 song (“La complainte du partisan”) of the French resistance to Nazi occupation. Tito came to prominence as leader of the anti-Nazi Yugoslav Partisans during World War II. Labudović too led the life of a partisan, becoming a national hero in Algeria. His death in 2017 was covered on Algerian television — with this prelude assembled by Mila Turajlic.

The theme of the symposium is “Love” — in all its forms, including love of country, patriotism, and political passions.

Registration for the Orphan Film Symposium, April 11-13, is open to all. (Tickets for the April 13 screening at 8pm can be purchased without symposium registration.) Visit www.nyu.edu/orphanfilm or write to orphanfilmsymposium [@] Gmail.com.

The 11th Orphan Film Symposium is also the culminating event in the 50th anniversary celebration of the NYU Tisch School of the Arts Department of Cinema Studies.

Pingback: الحنين إلى تيتو.. عبدالناصر وعصره – Alhoukoul