Aanya Gupta on Benvenuto Cellini & Luciano Gabarti

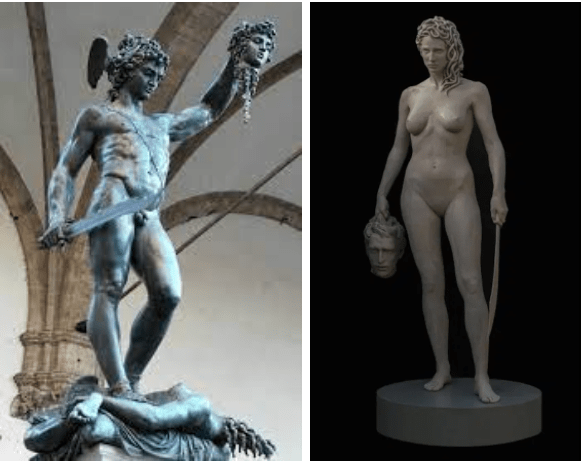

Florence, in the 15th Century, was one of the largest and richest cities in Europe in terms of art and culture, hence giving it the name the ‘cradle of the Renaissance’. Renaissance art is distinguished from medieval art primarily by physical realism and classical composition. A distinct sub-movement of Late Renaissance art was Mannerism: the deliberate pursuit of novelty and complexity. Perseus with the head of Medusa is one of the most well-known mannerist-style sculptures. It’s a bronze sculpture made by Benvenuto Cellini between 1545 and 1554, presented in the Loggia dei Lanzi in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, Italy. It presents the traditional Greek mythology where Perseus, the son of Zeus, kills Medusa by beheading her and is presenting the head to the Goddess Athena. He holds the head of Medusa in his left hand by grabbing the venomous snakes on her head, the face of Medusa expressing horror. The patriarchal practice led Cellini to portray Medusa as a frightening, ugly monster. In fact, during the patriarchal age, her decapitated head was often used to underscore the reality of her assault on the female form.

The mythology of Medusa goes as such – Medusa, one of the three Gorgon sisters, was a beautiful mortal, an exception to the family. Her features, specifically her beautiful hair, was admired by many, including the Greek god Poseidon. Poseidon impregnated Medusa (raped) in the virginal goddess, Athena’s temple. Enraged for desecrating this sacred space, Athena cursed Medusa with withering snakes in place of her hair, fanged teeth and a gaze that would turn anyone into stone – a hideous creature to be slain. Perseus, the demi-god and son of Zeus, with the aid of Athena and Hermes (messenger of the Olympian gods), manages to decapitate Medusa while she was asleep and present her head to Athena and Polydectes, the king of Seriphos (who had originally sent him on the quest). This narrative of the mythology robbed Medusa of her agency, pitted her and Athena against one another, while also praising a prototypical hero in Perseus.

Cellini’s Perseus with the Head of Medusa displays a likeness between the heads of Medusa and Perseus, making the victim’s and victor’s identities interchangeable. Both their faces and front profiles are strikingly similar, with downcast eyes and Perseus’ thick hair and helmet resembling the intertwined serpents on Medusa’s head and the coils of her blood. With the outstretched hand so near to his face, it seems like an invitation for the viewer to compare the two. But, like Medusa’s visage, her story shifted over time, always starting with when she possessed her power, her head getting severed and being used as a weapon, either as a monster or a damsel in distress.

Depicting a scene from Greek mythology, Cellini’s sculpture is not only elegant and enigmatic, but also a true demonstration of artistic skill. However, in today’s day and age, skill is not everything. History and mythology, both, are written from the perspective of the victors, always laced with implicit bias. But, Luciano Gabarti’s inversion of the myth of Perseus and Medusa destabilizes this ‘fixed’ history, creating a rather uncomfortable idea. The story of Perseus and Medusa is extremely paradoxical. Today, Medusa endures as an allegorical figure of fatal beauty or animage for superimposing the face of a detested woman in a position of power. In fact, Kiki Karoglou, associate curator in the Met’s Department of Greek and Roman Art, writes “Medusa, in effect, became the archetypal femme fatale: a conflation of femininity, erotic desire, violence, and death. Beauty, like monstrosity, enthralls, and female beauty in particular was perceived — and, to a certain extent, is still perceived — to be both enchanting and dangerous, or even fatal.”

Believing that this sculpture portrayed the myth at its worst, Gabarti presented a fresh perspective on this mythology, highlighting key ideas of the 21st Century through his Medusa with the Head of Perseus (2008). His primary intention in creating the sculpture was to protest against the traditional representation of Medusa and her myth over the centuries, such as the way they are depicted earlier. Placed across from the New York County Criminal Courthouse, Gabarti states, “My hope is that when people walk out of the courthouse, they will connect with the statue and they will have either have accomplished a comfortable sense of justice of themselves or feel empowered to continue to fight for equality for those being persecuted.”

In fact, this sculpture became one of the most important figures as part of the #MeToo movement against sexual assault and violence. Providing hope to millions of suppressed women across the world, Gabarti’s Medusa portrays her as a brave survivor who did not allow injustice to destroy her, but instead made her bolder and stronger, reversing the imagined gender roles.

CITATION –

Gershon, Livia. “Why a New Statue of Medusa Is so Controversial.” Smithsonian Magazine, Smithsonian Magazine, 13 Oct. 2020, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/controversial-metoo-medusa-statue-unveiled-180976048/. Accessed 30 July 2021.

Meier, Allison. “The Beauty and Horror of Medusa, an Enduring Symbol of Women’s Power.” Hyperallergic, Hyperallergic, 20 Mar. 2018, hyperallergic.com/432102/dangerous-beauty-medusa-in-classical-art-metropolitan-museum/. Accessed 30 July 2021.

GreekMythology.com. “Medusa – Greek Mythology.” Greekmythology.com, GreekMythology.com, 13 Mar. 2018, www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Creatures/Medusa/medusa.html. Accessed 30 July 2021.