Joyce Chen, On Artemisia Gentileschi

Artemisia Gentileschi is widely recognized as one of the most accomplished seventeenth-century painters, initially following in the style of revolutionary Baroque painter Carvaggio. Her story, once an almost forgotten piece of history, was resdiscovered in the 20th century as a feminist legacy. It tells the narrative of the worst chapter in the life of the talented painter. Rather than the vibrancy, brilliance, and profound emotions she left in her work, her life and legacy have been characterized by a single dark moment. If you’ve heard of Artemisia Gentileschi, you’ll likely know her as “the female painter who was raped.”

Gentileschi was familiar with the egregious injustices that constitute being a woman. 17-year-old her was on the cusp of adulthood when she was raped by her tutor, Agostino Tassi. What is remarkable about her case is not because sexual assault was uncommon back in 16th century Rome, but rather because there was a seventh-month trial— during which Gentileschi was shamed and slandered, subjected to a gynecological exam, and was tortured with thumbscrews around her fingers, all in order to test the truthfulness of her testimony.1 For an artist, this form of torture was devasting. Ultimately, the court found Tassi guilty; yet he soon escaped punishment thanks to papal protection. In attempt to salvage her sullied reputation, she was swiftly married off to her unremarkable husband in Florence. She led a long and successful career until her 60s, yet her pieces which receive almost all critical attention today where made when she was still in her teens or early twenties.

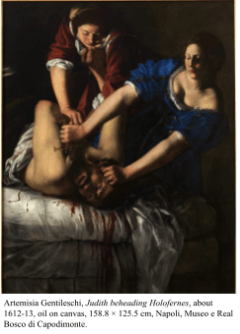

Judith Mann, exhibit curator of Gentileschi’s work at Rome’s Palazzo Braschi, says that historians’ fascination with the victim long overshadowed appreciation of her art. “She is a phenomenon in terms of the history of art, because we really understood her life far earlier than we cared, really, about her painting”2 Mann says. For a long time, it has been conventional to interpret Gentileschi’s paintings exclusively as her fantasizing revenge on the men who harmed her. Most famously, perhaps, is her interpretation of the biblical story Judith Beheading Holofernes, in which Judith took it upon herself to seduce the general Holofernes and decapitate him in his sleep. Gentileschi’s interpretation of Judith sharply contrasts with previous interpretations where she seemingly recoils fom slaying the man. Gentilschi’s Judith bears an expression of cruelty, determination, devoir, and a

overshadowed appreciation of her art. “She is a phenomenon in terms of the history of art, because we really understood her life far earlier than we cared, really, about her painting”2 Mann says. For a long time, it has been conventional to interpret Gentileschi’s paintings exclusively as her fantasizing revenge on the men who harmed her. Most famously, perhaps, is her interpretation of the biblical story Judith Beheading Holofernes, in which Judith took it upon herself to seduce the general Holofernes and decapitate him in his sleep. Gentileschi’s interpretation of Judith sharply contrasts with previous interpretations where she seemingly recoils fom slaying the man. Gentilschi’s Judith bears an expression of cruelty, determination, devoir, and a

1 Klowden, T. (2018, October 7). 400 years ago, an Italian artist risked everything to publicly accuse her rapist. Quartz. https://qz.com/quartzy/1413735/400-years-ago-an-italian-artist-risked-everything-to-publicly-accuse-her-rapist/.2 Poggioli, S. (2016, December 12). Long seen As Victim, 17th Century Italian Painter emerges as feminist icon. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/12/12/504821139/long-seen-as-victim-17th-century-italian-painter-emerges-as-feminist-icon.

lust to end her own misery. Thus, it isn’t hard to see why it has been often brought up in relation to recent rape-revenge fantasies in stories of wounded women turned mad with wrath.

But let us not allow sexual violence and the female stereotype of revenge to define the artist. It’s an overly simplistic, reductionist reading of her work. While it would be foolish to not consider her personal life when it comes to reading her work, it would be an utter traversity to reduce all her life’s work as responses to rape and trial. Gentileschi’s biography feels frequently warped and forced upon her work, masqueraded as a gender-progressive concern. It objectifies the artist, disregarding the qualities that made her a masterful panter. Rather than a story of revenge, Judith Beheading Holofernes could be alternatively interpreted as a story of daring, political collaboration to murder by two women at war. Her work exudes the confience of an artist who asserted her place in history, despite the obstacles she faced.

The world owes Artemisia an apology. We did injustice to her artistic and cultural influence, by rehashing the salacious details of her attack and restraining her work to exist only under Tassi’s shadow. To call for a different kind of discourse around Gentileschi, is to celebrate and study her masterful depictions of wounded women, and also to recognize her many paintings that exist beyond those tropes. The world could have done Artemisia Gentileschi far better, and we can do better now.