Reading Reflection 2: Machine Art and Kinetic Art

The historical evolution of “machine art” and “kinetic art” reveals a profound shift in the artistic landscape. It is significantly impacted by technological advancements and changing perceptions of art’s relationship with machines. Initially, “machine art” was closely associated with the celebration and aestheticization of the machine as a symbol of modernity and technological progress. This conception is deeply rooted in the early 20th century, especially within movements like Futurism and Constructivism, which glorified the machine as an emblem of a new era. Kinetic art, emerging later, expanded this idea by incorporating movement, thus shifting the focus from the static representation of machines to the dynamics of mechanical motion.

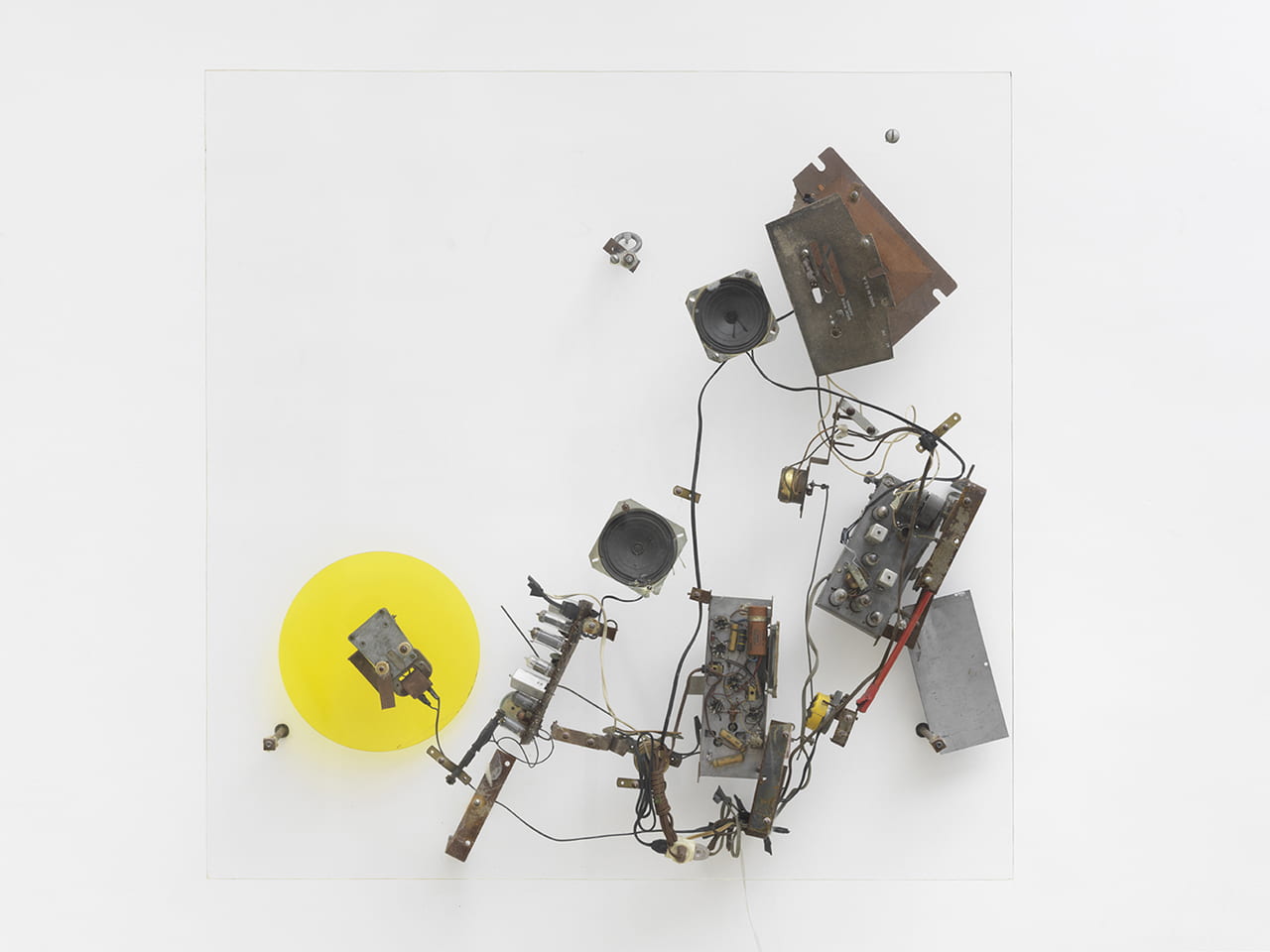

Jean Tinguely and Pol Bury, two artists prominently featured in the context of kinetic art, offer distinct approaches to integrating machine aesthetics into their works. Tinguely’s works, such as “Radio Drawing” (1962), epitomize a playful, ironic, and at times critical engagement with technology. His creations often featured machine parts and objects combined into whimsical assemblages. The creations challenge conventional notions of machine efficiency and functionality. This aligns with Andreas Broeckmann’s notion of kinetic aspects in machine aesthetics, where the emphasis is on mechanical movement often employed to reflect humorously or ironically on technical functionality.

Pol Bury’s approach to kinetic art, on the other hand, emphasizes subtle, almost imperceptible motion, marking a distinct departure from the more pronounced movements in Tinguely’s works. Bury’s works often involve minimal, trembling motions that alter viewers’ perceptions without dramatically transforming the form of the sculpture itself. This subtlety aligns with Broeckmann’s concept of the formalist aspect of machine aesthetics, which emphasizes the beauty of functional technical forms, albeit in Bury’s case, through understated kinetic interventions.

The role of machines within media arts projects, as exemplified by these artists, goes beyond mere representation or functional use. They become integral to the artistic narrative and contribute to a broader discourse on the relationship between technology and human experience. Tinguely’s humorous and critical engagement with machines questions our dependence on and perception of technology, while Bury’s subtle kinetics invite contemplation on the nuances of motion and time.

In conclusion, the transformation in the use of “machine art” and “kinetic art” over time reflects a deeper evolution in how artists perceive and interact with technology. From an initial fascination with the machine as a symbol of progress, artists like Tinguely and Bury have navigated through to a more nuanced, critical, and exploratory engagement with technology, thus expanding the boundaries of artistic expression.