“Autohistoria is a term I use to describe the genre of writing about one’s personal and collective history using fictive elements, a sort of fictionalized autobiography or memoir; and autohistoria‐teoría is a personal essay that theorizes” (Gloria Anzaldúa, 2009)

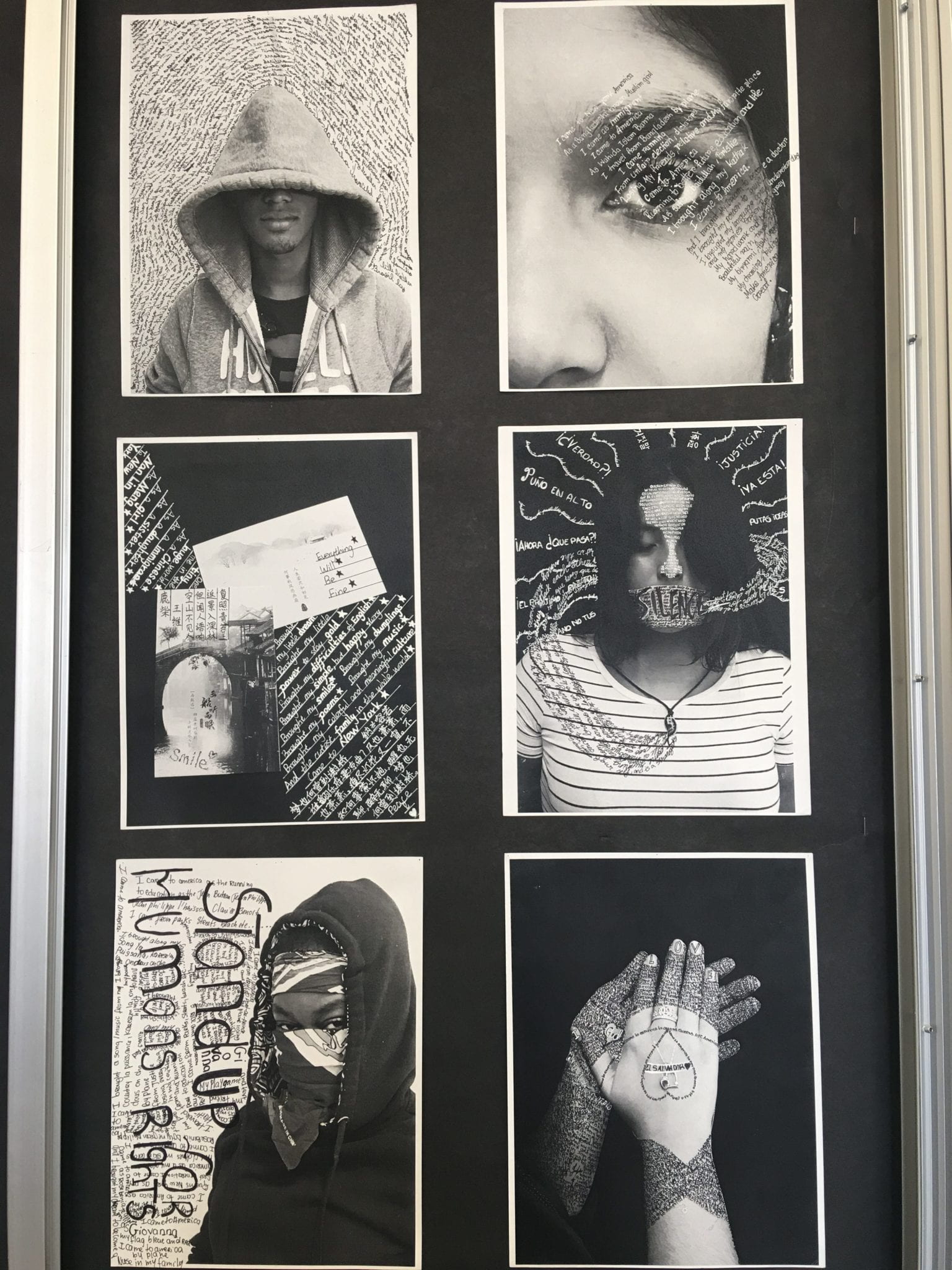

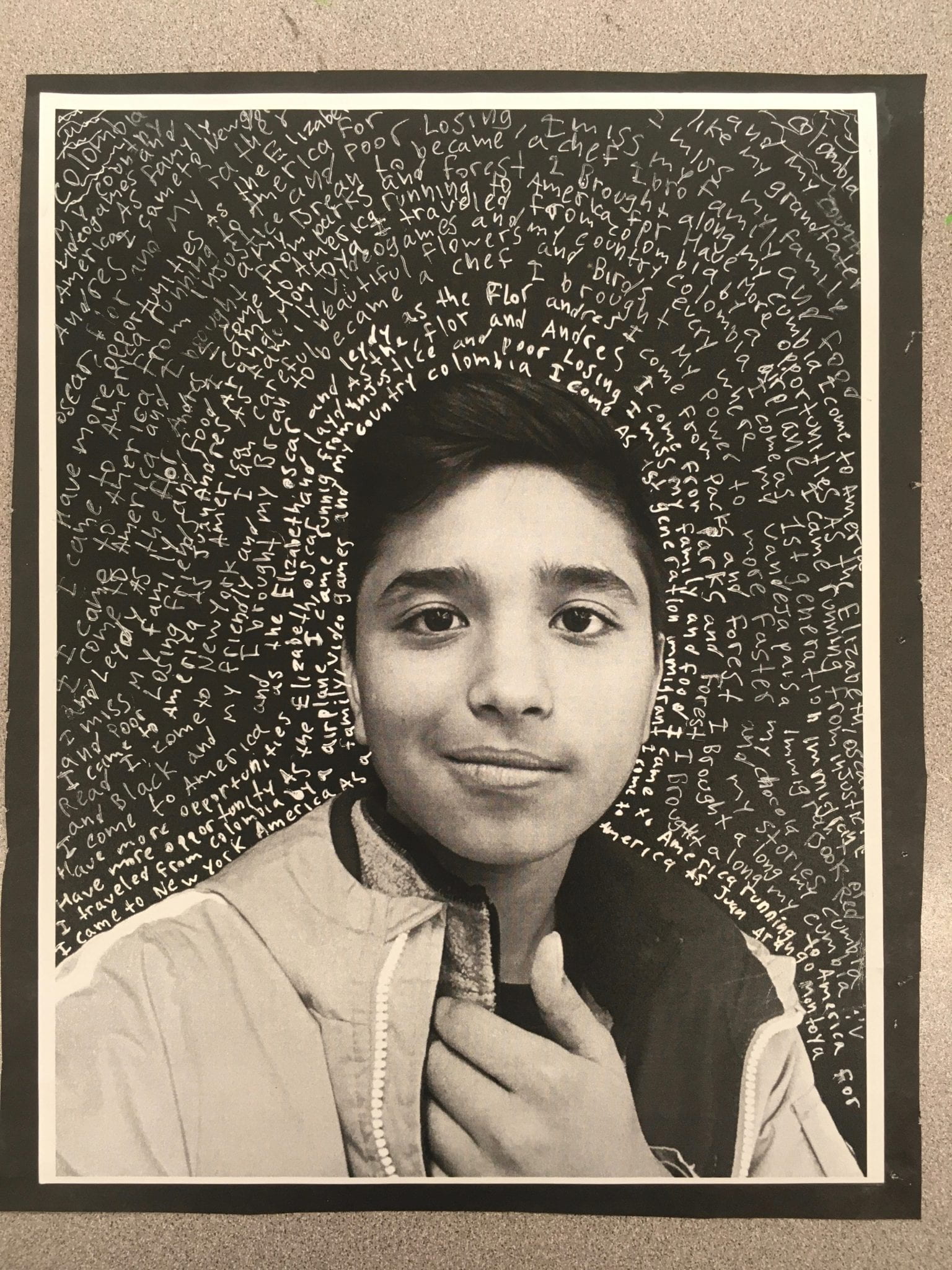

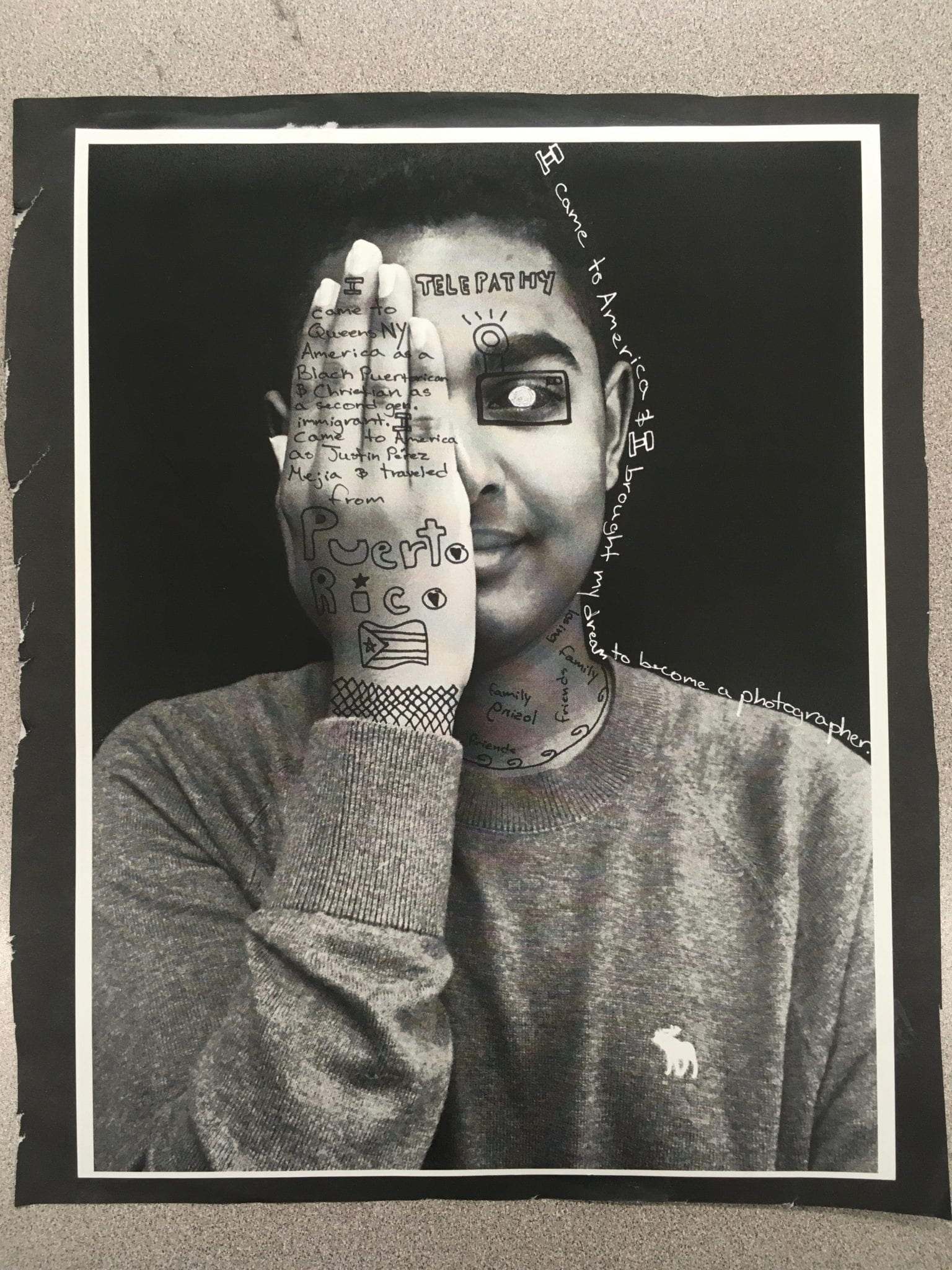

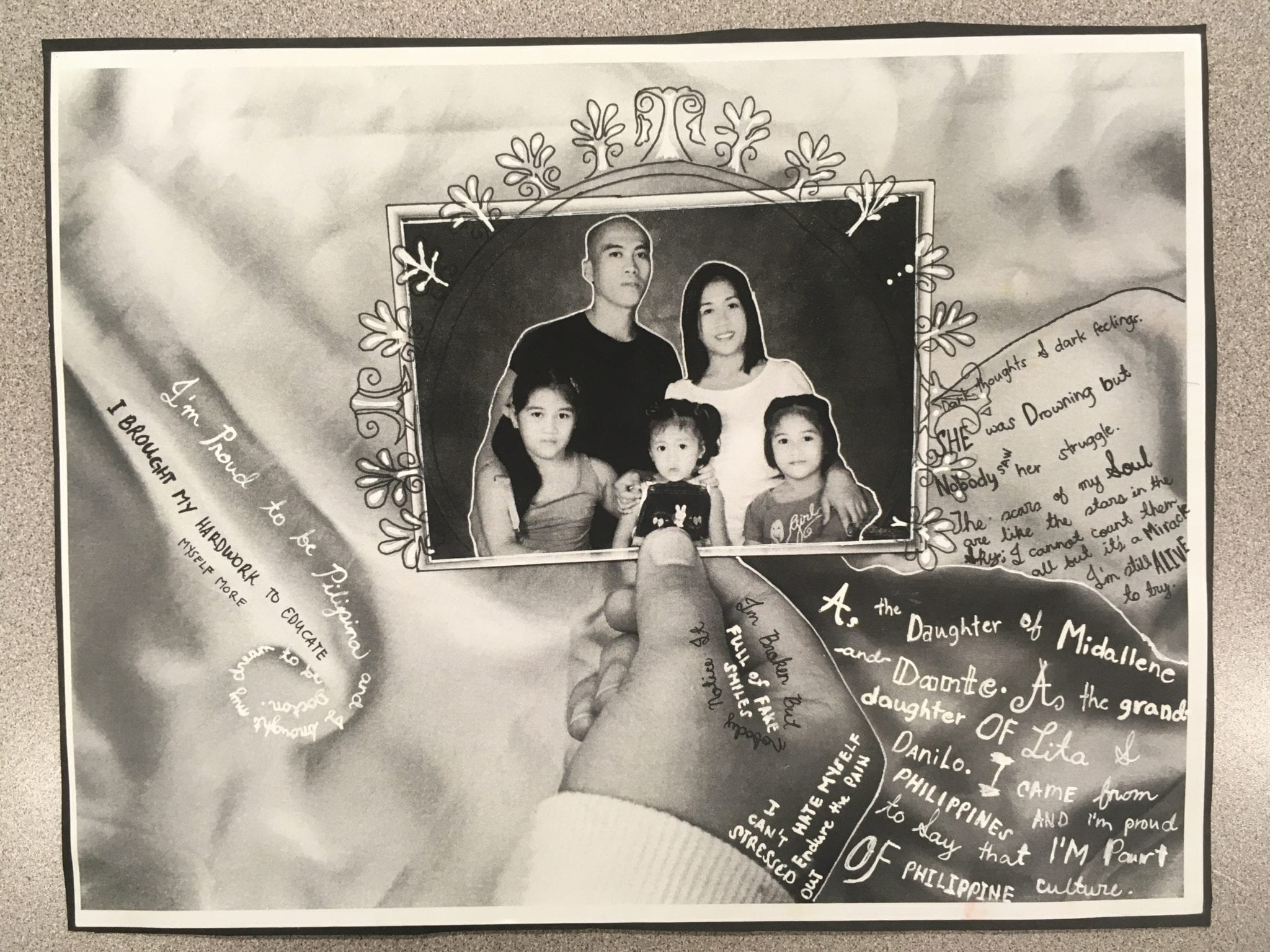

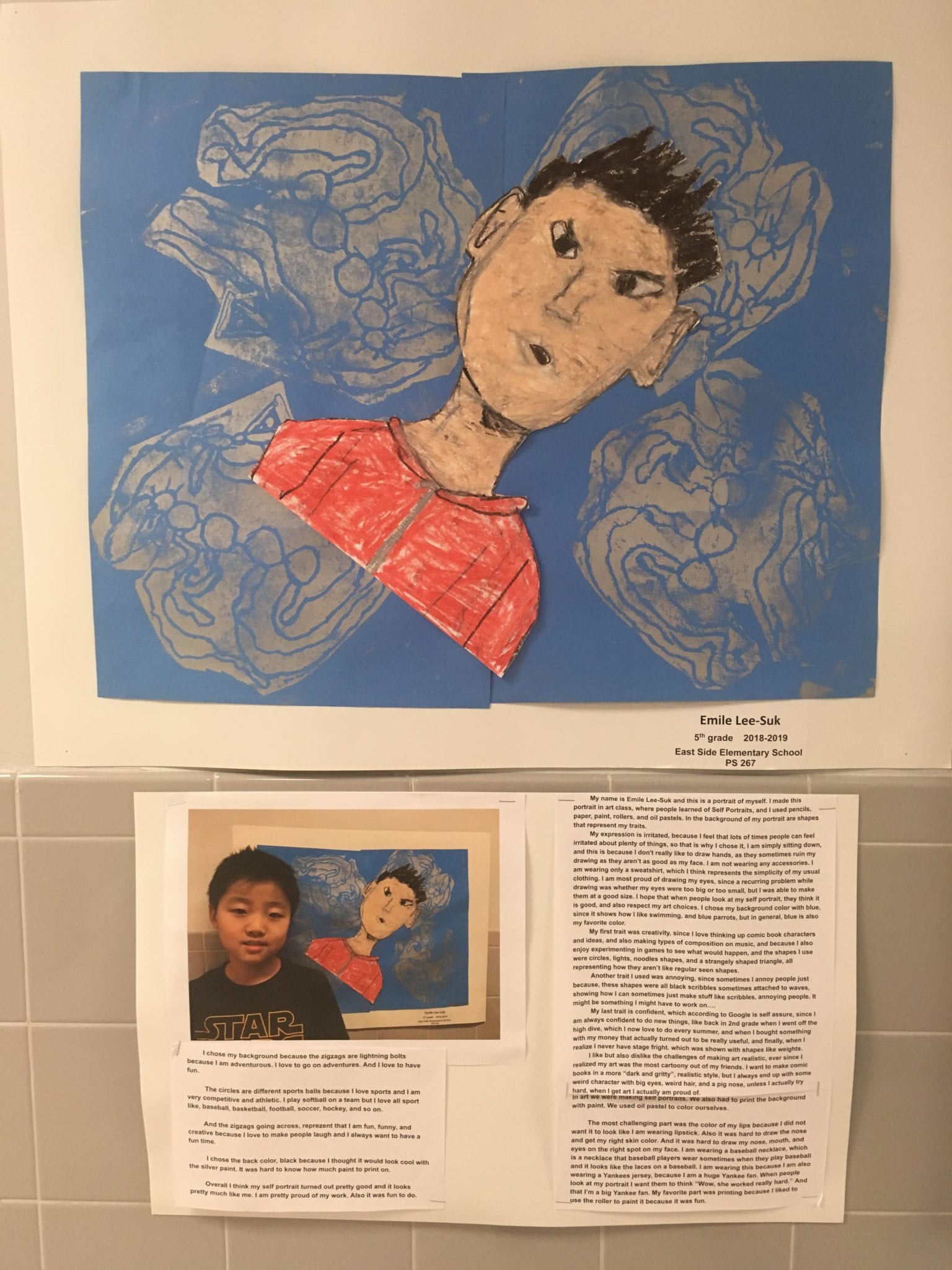

The brilliant Chicana feminist writer, theorist, and activist Gloria Anzaldúa used the term Autohistoria to describe a form of writing/theorizing that combined personal narrative to help shape social and relational understandings of the world. In the class, Race, Education and the Politics of Visual Representation, students used Anzaldúa’s notion of Autohistoria to reflect on different aspects of identity and represent memories and relationships to experiences of race, class, and gender/sexuality using visual and written forms. Students synthesized multiple memories/identities into a single representation using strategies of layering, juxtaposition, and connection.

My Autohistoria began as three separate pieces, each reflecting on a different part of my identity, which I destroyed before I finally wove them all together. I wrote about my gender/sexuality identity in a journal, reflecting more specifically on the reproductive privileges I hold as a white cis woman. I tore up the pages and twisted them into strands to be woven. The second piece is a reflection on the predominantly white space I occupy and its repercussions on others. I re-drew real estate signs posted around the neighborhood I’m currently living in with my dad and stepmom. The language on the signs use racist language like “colonial living” in order to keep the space as white as possible. I cut these up in order to weave into the piece. The last element is simply recycled old clothes and pantyhose I cut up to weave with as a symbol of my childhood experience growing up in a working class family that saved and reused everything.The creation of each piece, the act of destroying them, and the weaving process served as a kind of questioning, meditation, and reflection about where I currently sit with my identities and the privilege I hold within each.

This piece is about ways in which I’ve failed to meet expectations (racially, gender expectations, socio-economic status). I am exploring the extreme pressure felt from childhood in a society to fit or you are a failure, through the eyes of both men in my life and phrases I’ve had lobbed at me repeatedly. Every number, phrase, picture, is a measure of me and personal – but also quantified through a system or person separate from myself. To create this piece I started by drawing out several measuring tapes and a frame, I wanted those items to act as constraints. I collected photographs of personal meaning and edited them to reflect the end truth that was unknowable when the picture was originally taken.

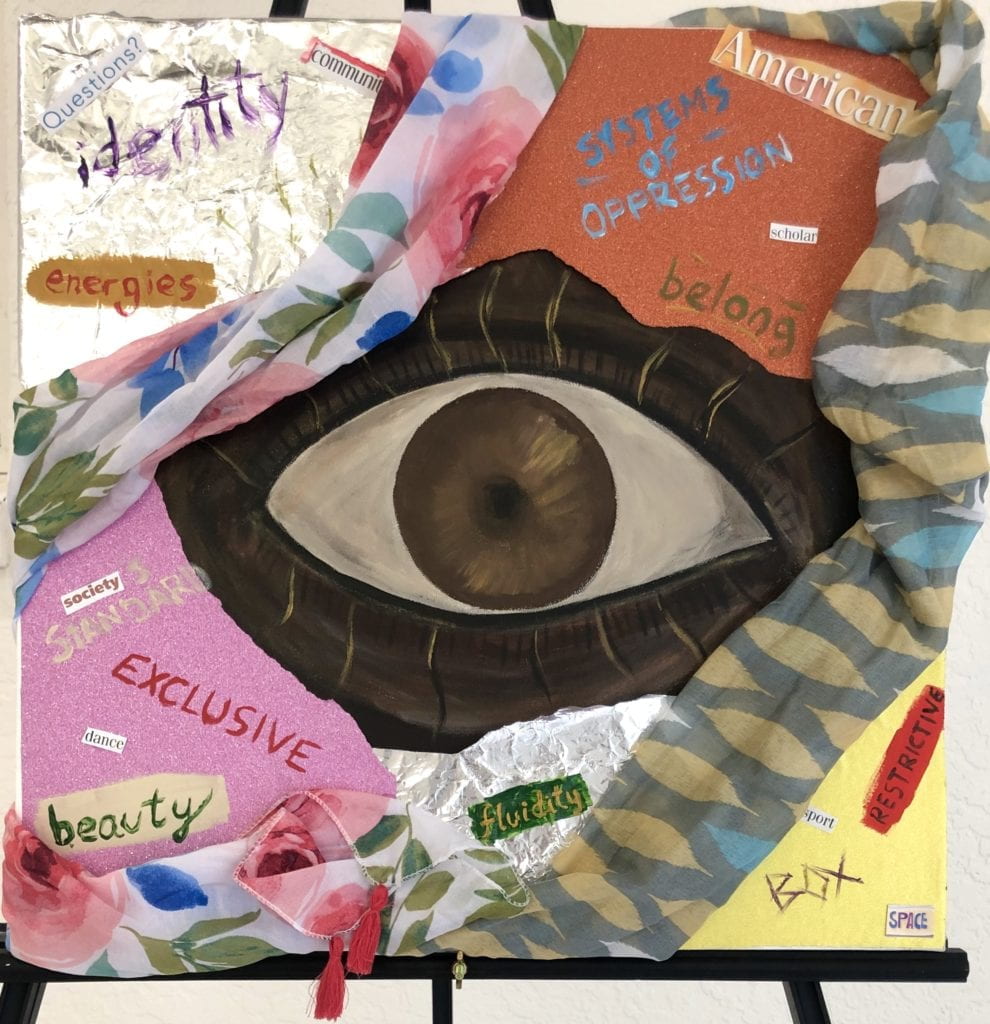

This piece speaks to the juxtaposition of how I’ve seen myself throughout my life and how others see me. The identities that society imposes on me have always felt restrictive. Anywhere from gender norms to racial expectations. In this piece I used different textures and mediums to depict the fluidity, vastness, and beauty of my identity; something I continue to discover, something that can’t be contained in any label and goes beyond what the eye can perceive.

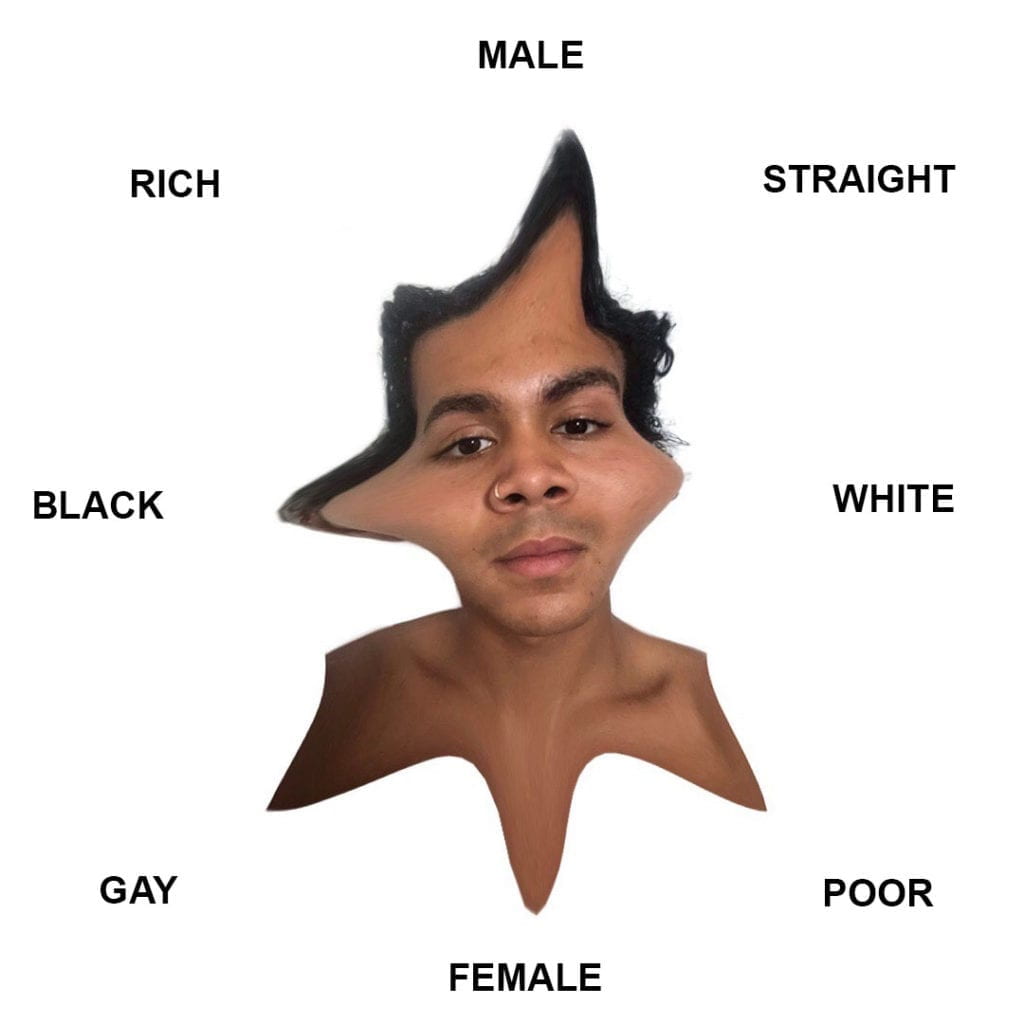

For this piece I thought about how my perception of self has been greatly influenced as well as distorted by the binary system that society uses when categorizing identities.

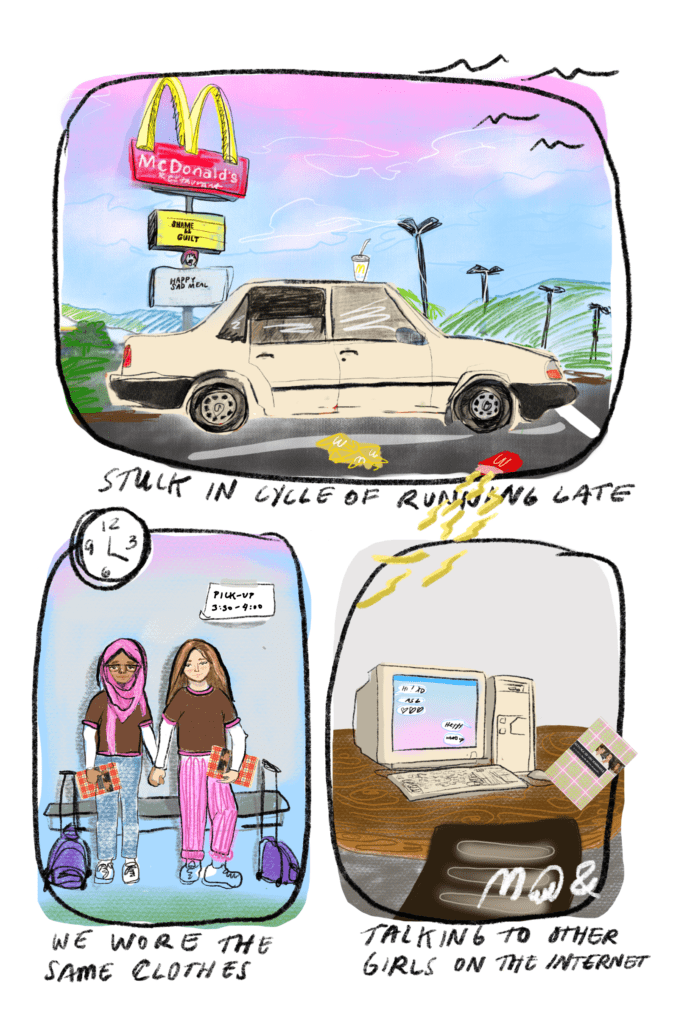

When making this piece to reflect on my personal background (race, class, gender/sexuality) I found that my class (working class) was always at the forefront of my mind. It showed itself in where I lived, what I ate, how much time my mom had, what brands we could afford. It was a lack that I was always trying to cover up. Conversely, growing up in a mostly white suburban setting, I rarely thought about my racial background (white) as a kid. I think this speaks to the dominance and power of whiteness. That white supremacy is so all encompassing that it becomes almost invisible (to those who benefit from it), and even more poisonous because of its invisibility. In this white supremacist capitalist society, everyone outside of this “norm” (whether it’s race, class, gender, sexuality, etc) is forced to reckon with an entire system built to reinforce the “norm” and punish everyone outside of it in order to protect it’s power.

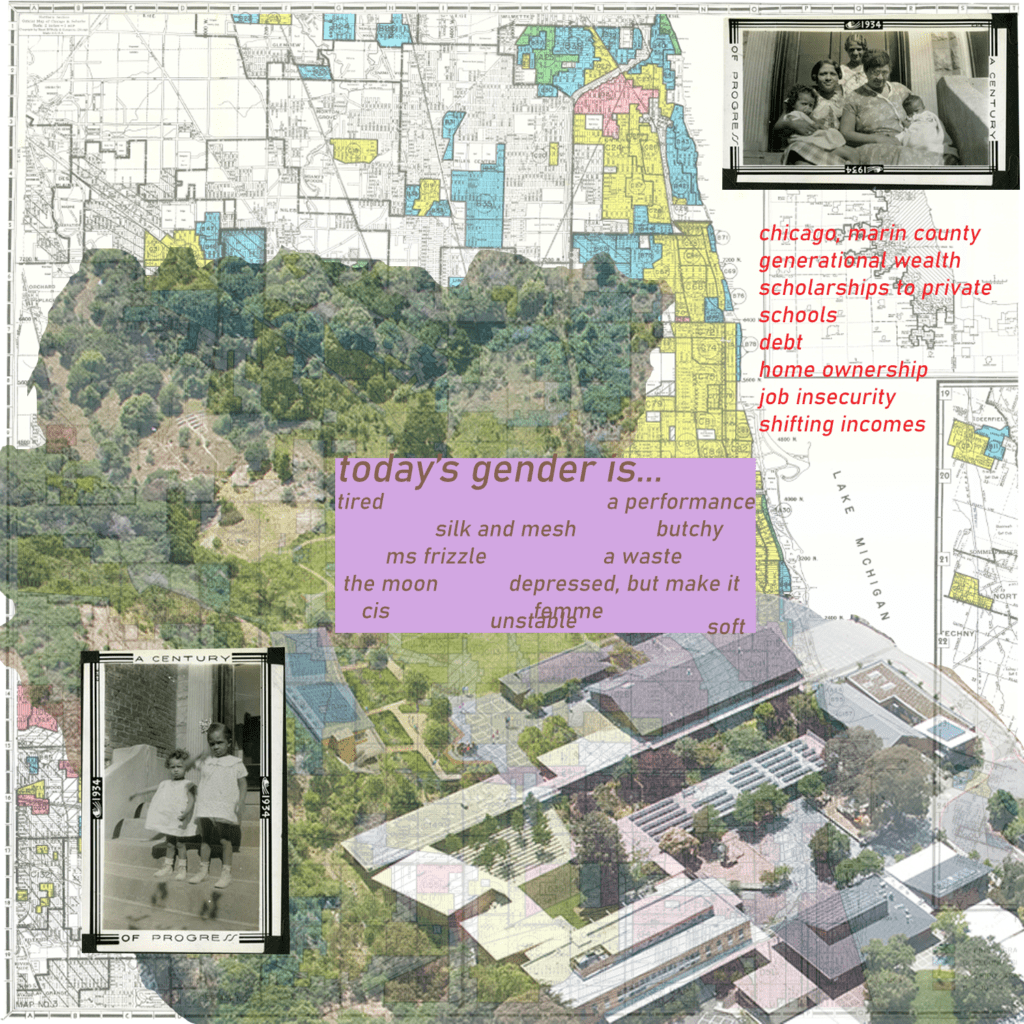

While putting together my autohistoria, I thought a lot about geography and how the places I’ve lived deeply inform my sense of self, especially in relation to race and class. Layered in the background is a redlining map of Chicago from the 1930s, and a bird’s eye view photograph of my private elementary and middle school in Marin County, CA–the two places where I grew up and experienced very conflicting realities defined by structural racism and classism. I also included photographs from my great-grandmother Carrie’s photo albums, which I remember looking through as a child and trying to understand myself. On the top layers of the collage, I added some of the words that came up from a free-write I did exploring my class, gender, and sexual identities.

In this work, I stand in front of a boarded store-front on Broadway Lafayette. The Original work is replaced with an image of the Puerto Rican flag adorned by roses, leaves, and graffiti. It was created based on my racial identity, gender, and sexual identity. I also hint towards economic identity very briefly.

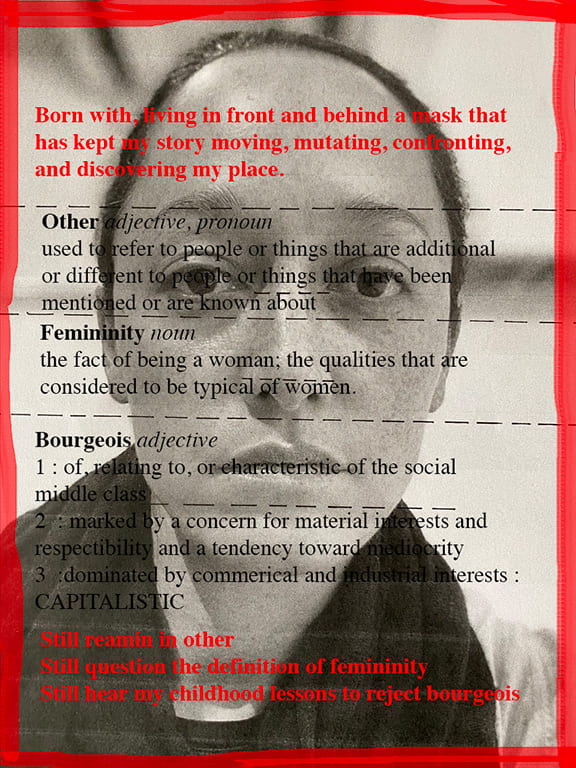

As a child I was the only multicultural kid in my school, as a teenager I was a late bloomer who never felt feminine enough, and as an adult I continue to experience the wide disparities of social/economic class in this world. These indelible memories define and challenge me. More often than not when I meet people there’s a pause, a quiet gap between us because I don’t fit into one category of race or ethnicity. My mother is Chinese/Korean, born in Shanghai and my father is of Russian Jewish descent, born in Brooklyn. She is the radical, he the hippie. The gender roles in society never reflected my home life and the political left leaning consciousness my parents raised me on was always difficult to find amongst my peers. As an adult I’ve found my way, my companions, and my place as I continually consider my past with my present state of mind.

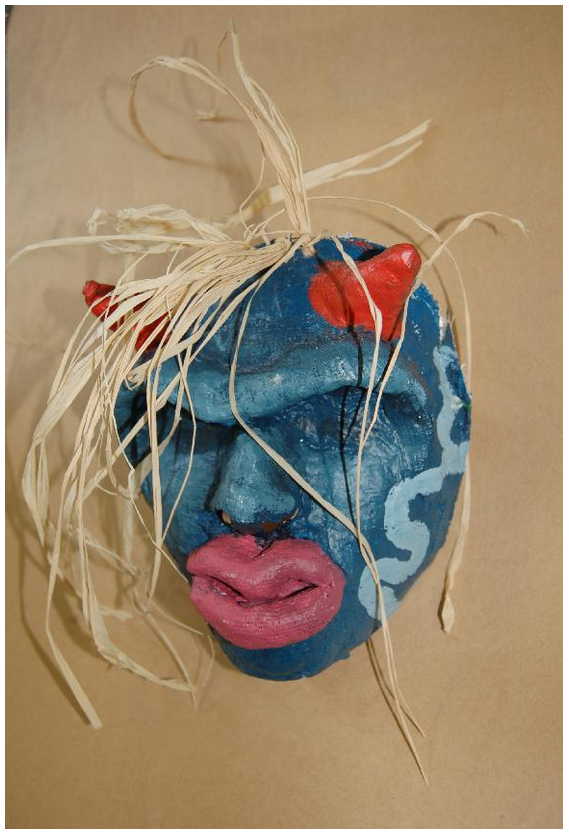

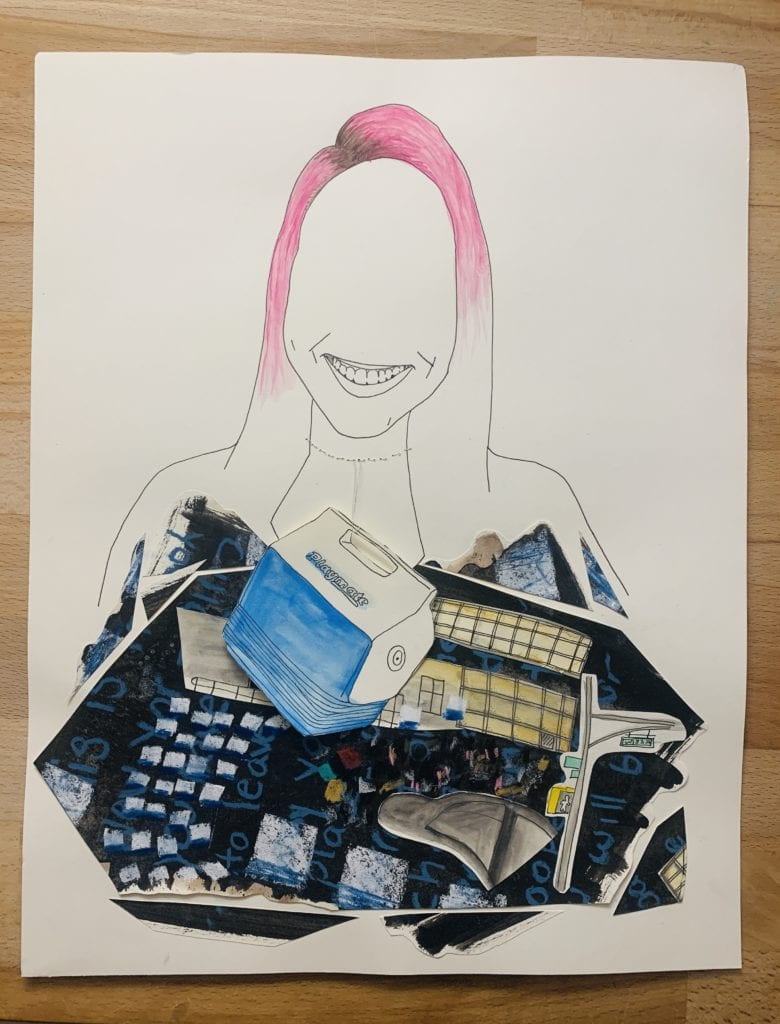

This self portrait reflects the balance between my inner self and my outer self, as they relate to outside societal influences and ideologies. In this piece I am trying to explore the idea of performative presentation of gender, race, and socioeconomic identities.

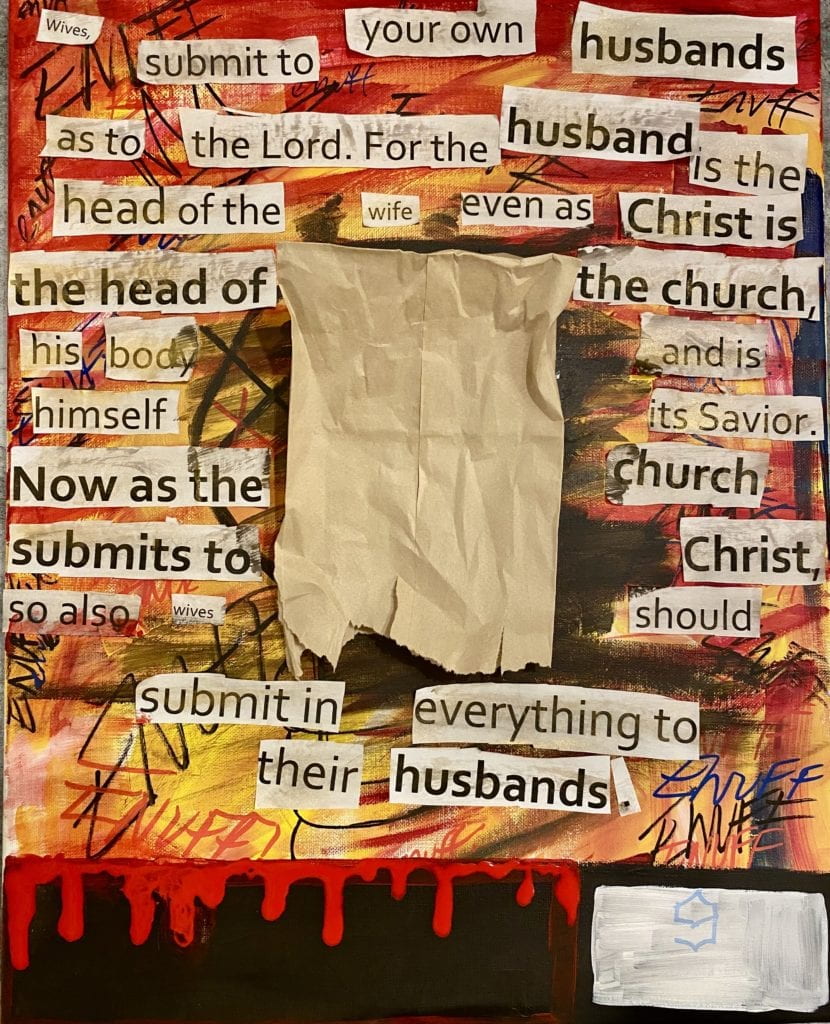

House Negro pulls from all three areas of my first or most recent experiences involving my identity. Growing up in Detroit, I always knew I was black since Detroit is nearly 80% African American. Detroit is one of the most poverty stricken cities in Michigan even though we are categorized as one of the most talented and hard working cities in Michigan. Being in Detroit, I didn’t understand my privilege of having lighter skin until conversations I had while playing with other black children. It was pressed upon me that I would have been a “House Negro” because my skin was lighter than a paper bag. This same narrative is spread over into the Bible verse Ephesians 22-24, a scripture that never settled with me as a woman. As my husband would be my master and I would have to submit and obey him like Christ. Like my duties would be to serve him at all times. All three themes reflect on my way of growing up and finding myself in these constant states of oppression.

My first exposure in realizing gender came from my father’s repeated guidelines on what being a girl/ young woman meant to him: long hair, not as receptive to new or technical information as a boy, clean and neat nails /hands, … These details Are voices-over in haiku form while the illustrated portrait shifts from images of my younger self with long hair, young adult self with my hoop earrings and my older self with earrings and glasses. I use this moving image as I recall my very first and recent memory of racial identity. Since I was a kid strangers have commented on and have been surprised by me speaking English. ”Where are you from?” And I’d reply✨ “Brooklyn”. And that would infuriate them and they’d demand a “correct answer”: 👾”You KNOW what I mean! Where are you from-from?!” **** I’ve been on busses, trains, in supermarkets, at Target, waiting for the walk sign at an intersection, at school, at work, on my block, on my own stoop: when someone commented on my English and asked me: 👾”what’s your nationality?” ✨”I’m American.” I respond to quickly shut them up. I know what they want from me- I refuse to make it easy. This backfires sometimes ‘cause MANY times they reply: 👾”Are you sure?” ✨“Am I sure I was born here? Yes.” 👾”Where is your family from?” I include the voice over with the imagery to invite the viewer into the layered moments of which I’ve experienced daily. ✨✨✨✨

“Personal experiences – revised and in other ways redrawn – become a lens with which to reread and rewrite the cultural stories into which we are born.” – Gloria Anzaldúa, now let us shift….