Final paper for Principles of Empirical Research with Catherine Voulgarides

Research questions

Jamie Ehrenfeld is a colleague of mine in the NYU Music Experience Design Lab. She graduated from NYU’s music education program, and now teaches music at Eagle Academy in Brownsville. Like many members of the lab, she straddles musical worlds, bringing her training in classical voice to her work mentoring rappers and R&B singers. We often talk about our own music learning experiences. In one such discussion, Jamie remarked: “I got a music degree without ever writing a song” (personal communication, April 29 2017). Across her secondary and undergraduate training, she had no opportunity to engage with the creative processes behind popular music. Her experience is hardly unusual. There is a wide and growing divide behind the culture of school music and the culture of music generally. Music educators are steeped in the habitus of classical music, at a time when our culture is increasingly defined by the music of the African diaspora: hip-hop, R&B, electronic dance music, and rock.

The music academy’s near-exclusive focus on Western classical tradition places it strikingly at odds with the world that our students inhabit. In this paper, I examine the ideological basis for this divide. Why does the music academy generally and the training of music educators in particular hold so closely to the traditions of Western European classical music? Why has the music academy been slow to embrace African diasporic vernacular musics? Why does it outspokenly reject hip-hop? What racial and class forces drive the divide between music educators and the culture of their students? How might we make music education more culturally responsive? How can music educators support students in developing their own musical creativity via songwriting and beatmaking? What assumptions about musical and educational values must we challenge in order to do so?

Framing of research topic

Music education scholars commonly use “non-Western” as a shorthand for music outside the European classical tradition. This might lead one to naively believe that hip-hop is non-Western music. But it arose in the United States, so how can that be? Are our racial and ethnic minorities part of our civilization, or are they not? While the American cultural mainstream has increasingly embraced black musical styles, the music education field has not followed suit. As an example, consider a meme posted to a group for music teachers on Facebook. The meme’s original author is unknown. The caption was something like, “Typical middle school/high school student.” I will leave the person who posted it to Facebook anonymous, because they no doubt meant well.

The meme-maker is dismayed that young people do not care how little their music adheres to the stylistic norms of the Western European classical tradition. The author dismisses contemporary popular music and can not imagine why anyone else might enjoy it. The condescending presumption is that young people do not “really” enjoy pop, that they are being tricked into it by marketing and image, and that they are too lazy and ignorant to make critical choices. The choice of the word “molester” is a remarkable one, with its connotation of sexual violence. Classically trained educators feel their culture to be under attack, with their own students leading the charge.

Eurocentrism in American music education

In examining educational practice, we must look for the “hidden curriculum” (Anyon, 1980), the ideological content that comes along with the ostensible curricular goals. For example, The Complete Musician by Steven Laitz (2015) is a widely used college-level theory text. (I used a similar book of Laitz’s to fulfill my own graduate music theory requirement.) The title asserts an all-encompassing scope, but the text only discusses Western classical harmony and counterpoint. Other elements of music, like rhythm or timbre, receive cursory treatment at most. African diasporic and non-Western musics are not mentioned. The hidden curriculum here is barely even hidden. Mcclary (2000) asks why the particular musical conventions that emerged in Europe during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries appealed so much to musicians and audiences, what needs they satisfied, and what cultural functions they performed. We might ask, since those conventions no longer appeal to most musicians or audiences, whose needs are being satisfied by school music? What cultural functions is it performing?

America has embraced every black musical form from ragtime through trap. But while our laws and culture have become less overtly racist over time, the oppression of people of color continues, African-Americans especially. For example, while they are no more likely to use drugs than white people, black people are many times more likely to be incarcerated for it. A white applicant with a felony drug conviction is more likely to get a callback for an entry-level job than a black applicant with no criminal record at all (Pager, 2007). Our large cities are extraordinarily segregated, with black neighborhoods isolated and concentrated (Denton & Massey, 1993). Perhaps this isolation has contributed to the evolution of hip-hop and its radical break with European-descended musical practices. Perry (2004) argues that, while hip-hop is a hybrid music, it is nevertheless a fundamentally black one due to four central characteristics:

(1) its primary language is African American Vernacular English (AAVE); (2) it has a political location in society distinctly ascribed to black people, music, and cultural forms; (3) it is derived from black American oral culture; and (4) it is derived from black American musical traditions (Perry 2004, 10).

The white mainstream adores the music while showering the people who created it with contempt (Perry 2004, 27).

Black music versus white educators

If the popular mainstream is dominated by innovations in black music, the field of musical education is unified by its extraordinary whiteness, both demographically and musically. Prospective teachers tend to be white, and come from suburban, low-poverty areas (Doyle, 2014). There is corresponding disproportionality among participants in formal music classes and ensembles—privileged groups are overrepresented, while less-privileged groups are underrepresented. This is true for white students versus students of color, high-SES students versus low-SES students, native English speakers versus English language learners, students whose parents have more versus less education, and so on (Elpus & Abril, 2011). Some of the disparity is due to the fact that schools in less privileged communities are less likely to offer music in the first place. But the disparities hold true among schools that do offer music, and persist even when schools supply free instruments. Lack of access alone can not explain the overwhelming whiteness and privilege of most participants in school music.

A great deal of research shows enrollment in school music declining precipitously for the past few decades. Budget cuts alone can not explain this decline, since enrollment in other arts courses has not declined as much (Kratus, 2007). As America’s student population becomes less white, its Eurocentric music education culture is evidently becoming steadily less appealing. Finney (2007) attributes the gap between music educators and their students to differing musical codes. “Teachers tend to use elaborated codes derived from Western European ‘elite’ culture, whereas students use vernacular codes… Students and teachers are therefore in danger of standing on opposite sides of a musical and linguistic chasm with few holding the key to unlock the other’s code” (18). Williams (2011) points to large ensemble model of school music that was imported to the United States from the European conservatory tradition in the early twentieth century, and which has barely changed since. Music educators teach what they learned, and what they learned is likely to have been the conservatory-style large ensemble.

Is the solution to expand the canon of “acceptable” music to include more artists of color? A typical undergraduate music history curriculum now tacks Duke Ellington or Charlie Parker onto the end of the succession of white European composers. But the canon is a political entity, not just an aesthetic one. If we try to expand the canon to include a greater diversity of musics, we will fail to challenge the basic fact of its existence and its role in academic culture. “[T]he canon is an epistemology; it is a way of understanding the world that privileges certain aesthetic criteria and that organizes a narrative about the history and development of music around such criteria and based on that understanding of the world. In other worlds, the canon is an ideology more than a specific repertory” (Madrid 2017, 125). Diversity is of no help if we simply use it to perpetuate privilege and power inequalities. “What does it mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy? It means that only the most narrow parameters of change are possible and allowable” (Lorde 1984, 110). Rather than making incremental changes to the canon, we must ask how we can re-orient the basic assumptions of music education, its mission, its values, and its goals.

Literature review

In this section, I examine the present state of music education scholarship addressing the racial and class dynamics of music education, as well as the rise of culturally responsive pedagogies, particularly surrounding hip-hop.

Who is school music for?

By excluding entire categories of music and musicianship from the official curriculum, music educators send powerful and lasting messages to students (and everyone else) about what our society values and what it does not (Bledsoe, 2015). I am living proof; my own experiences with school music left me bored and alienated, and I came to the conclusion that I was not a musician at all. It took me years of self-guided practice to disabuse myself of that notion. I have had endless conversations with non-classical musicians at every level about how they do not regard themselves as “real” or “legitimate” musicians, no matter how professionally or creatively accomplished they may be. Fortunately, school music is not the only vector for music education. Most popular musicians learn informally from peers or on their own, a method that has become easier thanks to the internet. Still, the stigma of “failure” is a heavy psychological burden to overcome.

School music is usually competitive. There is a competitive process to become part of an ensemble, and those ensembles compete intramurally in much the same way that sports teams do. Conservatories that produce professional musicians need to be competitive. But should we continue to model all school music on the conservatory? The similarity between school ensembles and sports teams should trouble us. Schools are not obligated to let everyone play varsity football, regardless of ability. However, we do believe that schools should teach everyone reading and math. Our efforts to support struggling readers and math learners may be inadequate or even counterproductive, but at least we try to meet all students’ needs, and we certainly do not exclude low performers from studying these subjects entirely.

Some music teachers appear to exhibit the attitude of a physician who complains that all the patients in the waiting room are sick! In other words, they prefer to work only with the talented, ‘musically healthy’ few, when it is those who are in the most need of intervention who deserve at least equal attention (Regelski 2009, 32).

What if we held music teachers to the standards of math teachers rather than football coaches? We might follow the model of physical education classes and public health initiatives, prioritizing lifetime wellness over the identification and training of elite athletes only (Dillon, 2007).

Music and identity

In traditional aesthetic approaches to the Eurocentric canon, the locus of musical expressivity and meaning of the music is embedded entirely within the music itself. Listeners’ subjective experiences are not considered to be significant; our job is to decipher the formal relationships that the composer has encoded into the score. By contrast, Elliott and Silverman (2015) argue that we should take an embodied approach to musical understanding, seeing music as an enactive process emerging from the performance and listeners’ experience of it in social/emotional context. In the embodied approach, we see music as a tool for listeners to make their own meaning, to build their identity, and to communicate and modulate their emotions, all by means of bodily and social lived experience (van der Schyff, Schiavio & Elliott, 2016). Music is “a device for ordering the self” (DeNora 2000, 73). The role of music in building individual and group identity and a sense of belonging is especially critical in adolescence, when its ability to release or control difficult emotions may be literally lifesaving (Campbell, Connell & Beegle, 2007).

Music can also be the organizing principle behind new cultures and subcultures, a locus for tribal self-identification. Turino (2016) proposes that participatory music cultures offer an alternative form of citizenship, with the potential to be fundamental to our sense of self and a cornerstone of our happiness.

Fostering creative expression

Ruthmann (2007) suggests that we teach music the way that English teachers teach writing: use creative prompts that encourage students to develop individual authentic voices capable of expressing their own ideas and thoughts. Like writing generally, songwriting is hardly an elite or specialized practice. All young children spontaneously make up songs, which can sometimes be strangely catchy. My son wrote his first song at age four without any prompting or assistance, inspired by an episode of Thomas The Tank Engine (Pomykala-Hein, 2017). For many young people, music is entirely comprised of songs (Kratus, 2016). But after elementary school, school music is more about “pieces” than songs, symptomatic of the broader gap between in-school and out-of-school music cultures.

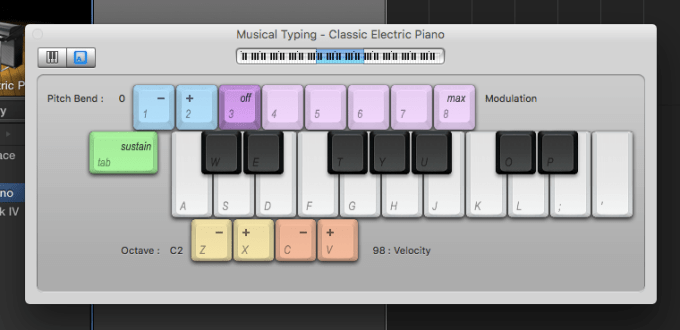

While music therapists have long taught songwriting, it is a rare practice in school music curricula. Kratus advocates songwriting for its therapeutic benefits, and for its lifelong learning benefits as well. Few adults have the opportunity to play oboe in an orchestra, but anyone with a guitar or keyboard or smartphone can write and perform songs. Historically, the technology for writing English has been dramatically more accessible than the technology for writing music, but that is changing rapidly. The software and hardware for recording, producing and composing music becomes cheaper and more user-friendly with each passing year. The instrumental backing track for “Pride” by Kendrick Lamar (2017) was produced by the eighteen-year-old Steve Lacy entirely on his iPhone. What are the other creative possibilities inherent in the devices students carry in their pockets and backpacks?

The psychological benefits of songwriting extend beyond musical learning. Like other art media, songwriting is an opportunity to practice what Sennett (2008) calls “craftsmanship,” defined as “the desire to do a job well for its own sake.” Craftsmanship is a habit of mind that “serves the computer programmer, the doctor, and the artist; parenting improves when it is practiced as a skilled craft, as does citizenship” (Sennett 2008, 9). Musical performers exercise craftsmanship as well, but not along as many different dimensions as songwriters and producers do.

Music creation is also a potential site of ethical development. We treat our favorite songs as imaginary people who we feel loving toward and protective of. This kind of idealization is akin to what we do “when we constitute others as persons, or when we invest others with personhood” (Elliott & Silverman 2015, 190). We imagine a personhood for the music, and we try to make that personhood real. In so doing, we learn how to create personhood for each other, and for ourselves. The point of musical education should not just be training in music, but developing ethical people through music (Bowman 2007, 2016). We can consider musical sensitivity to be a particular form of emotional sensitivity, and musical intelligence to be a particular application of emotional intelligence. Musical problem solving is an excellent simulator for social problem solving generally. Both in music and in life, the challenges are ambiguous, contingent, and loaded with irreconcilable contradiction. Performance and interpretation entail some musical problem-solving, but in the classical ensemble model that is typically the purview of the conductor. Songwriting poses musical problem-solving challenges to all who attempt it.

Hip-hop pedagogies

Brian Eno (2004) observes that the recording studio is a creative medium unto itself, one with different requirements for musicality from composition or performance. Indeed, no “composing” or “performing” need ever take place in modern studio practice. Eno is a case in point—while he has produced a string of famous and revered recordings, he does not consider himself to be adept at any instrument, and can not read or write notation. The digital studio has collapsed the distinction between musicians, composers, and engineers (Bell, 2014). The word “producer” is a useful descriptor for creators working across such role boundaries. In the analog recording era, producers were figures like Quincy Jones, executive managers of a commercial process. However, the term “producer” has come to describe anyone creating recorded music in any capacity, including songwriting, beatmaking, MIDI sequencing, and audio manipulation. We might expand the word further to include anyone who actively creates music, be it recorded, notated or live. To be a producer is a category of behavior, not a category of person.

Contemporary popular music is produced more than it is performed. This is nowhere more true than in the case of hip-hop, which in its instrumental aspect is almost entirely “postperformance” (Thibeault, 2010). The processes of producers like J Dilla and Kanye West resemble those of Brian Eno far more than those of Quincy Jones. This dramatic break with traditional musical practice poses major challenges for educators trained in the classical idiom, but it also presents new opportunities for culturally relevant and critically engaged pedagogy. Hip-hop-based education is mostly discussed in the urban classroom context, aimed toward “at-risk” youth (Irby & Hall, 2011). However, as hip-hop has expanded from its black urban origins to define the rest of mainstream musical culture, so too can it move into the educational mainstream as well.

There are several ways to incorporate hip-hop into education. Pedagogies with hip-hop connect hip-hop cultures and school experiences, using hip-hop as a bridge. Pedagogies about hip-hop engage teachers and students with critical perspectives on issues within the music and its culture, using hip-hop as a lens. Pedagogies of hip-hop apply hip-hop worldviews and practices within education settings (Kruse, 2016). Music educators can use hip-hop to enhance cultural relevance and connect to the large and growing percentage of students who identify as part of hip-hop culture. However, it is the use of hip-hop practices that most interests me as a research direction.

We should avoid using hip-hop as bait to get kids interested in “legitimate” music. Instead, we can apply the hip-hop ethos of authentic, culturally engaged expression to music education generally. Kratus (2007) points out that large ensembles are some of the last remaining school settings where the teaching model maintains a top-down autocratic structure, untouched by the cognitive revolution. This method does not create independently functioning musicians. How might we find ways for students to engage in music on their own cultural and technological terms? One method might be to do sampling and remixing of familiar music as an entry point into creation. This is the approach taken by Will Kuhn (personal communication, 2017), who teaches high school students to build songs entirely out of pieces of existing songs. Students can then replace those appropriated samples with material of their own.

Hip-hop has many controversial aspects, but none provokes the ire of legacy musicians more than the practice of sampling. There is a widespread perception that sampling is nothing more than a way to avoid learning instruments or hiring musicians. This may be true in some instances, but it is easy to identify examples of artists who went to considerable expense and trouble to license samples when they did not need to do so. For example, while Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of the Roots is a highly regarded drummer, he still uses sampled breakbeats in his productions. Why would he prefer a sample to his own playing? In hip-hop, “[e]xisting recordings are not randomly or instrumentally incorporated so much as they become the simultaneous subject and object of a creative work” (Culter 2004, 154). Samples have specific timbral qualities that evoke specific memories and associations, situating the music in webs of intertextual reference.

Rice (2003) encourages non-music educators to draw on the practice of sampling. Students might approach cultural artifacts and texts the way that producers approach recorded music, looking for fragments that might be appropriated and repurposed to form the basis of new works.

The pedagogical sampler, with a computer or without a computer, allows cultural criticism to save isolated moments and then juxtapose them as a final product. The student writer looks at the various distinct moments she has collected and figures out how these moments together produce knowledge. Just as DJs often search for breaks and cuts in the music that reveal patterns, so, too, does the student writer look for a pattern as a way to unite these moments into a new alternative argument and critique (465).

Rice advocates what he calls the “whatever” principle of sampling. In the hip-hop context, “whatever” can have two meanings. First, there is the conventional sense of the word, that everything is on the table, that anything goes. There is also the slang sense of “whatever” as a statement of defiance, indifference, and dismissal. In a pedagogical context, the “whatever” principle encourages us to be accepting of what is new and unexpected, and be dismissive of what is fake or irrelevant. As Missy Elliott (2002) puts it: “Whatever, let’s just have fun. It’s hip-hop, man, this is hip-hop.”

I asked Jamie Ehrenfeld, if she had written songs while getting her music degree, what kind of material might she have written? She responded:

I would think of bits of music in my head and then associate them with some other song I’d already heard and felt like nothing I could think of was really original, and I didn’t get that it’s okay that in writing a song having some elements of other songs can come together to make something new, and that actually being original is more of what existing pieces you weave together in addition to ‘original’ thought (personal communication, April 28 2017).

In other words, the sampling ethos might have validated the intuitive creative processes she was already spontaneously carrying out, whether she had realized those impulses in the form of digitally produced recordings or pencil-and-paper scores.

Can a work based on samples be wholly original? Perhaps not. But hip-hop slang offers a different standard of quality that may be more apposite: the idea of freshness. There are several different definitions of “fresh.” It can mean new or different; well-rested, energetic, and healthy-looking; or appealing food, water, or air. “Fresh” is also a dated slang term for impudence or impertinence. In hip-hop culture, “fresh” is one among many synonyms for “cool,” but it could be referencing any of the various original senses of the word: new, refreshing, appetizing, attractive, or sassy. Rather than evaluating music in terms of its originality, we might judge music by its freshness (Hein, 2015). A track that includes samples can not be wholly original by definition, but it can be fresh. It is this sense of making new meaning out of existing resources that animates the Fresh Ed curriculum (Miles et al, 2015), a culturally responsive teaching resource created by the Urban Arts Partnership. Rather than treating students as receptacles for information, Fresh Ed places new knowledge in familiar contexts, for example in the form of rap songs. When students are able to draw on their prior knowledge and cultural competencies, they are better equipped to engage and think critically.

Proposed methods

Luker (2008) describes the case that chooses you, or that you sample yourself into (131). My own trajectory as a musician and educator has made me an exemplar of the shortcomings of Eurocentric music pedagogy and the benefits of personal creativity through producing and songwriting; certainly it feels like this case chose me. Since my own motivations are borne out of subjective experience, and since my research questions were provoked by the experiences of others like me, my research into those questions must necessarily follow an interpretivist paradigm. In choosing methods aligning to that paradigm, I want to identify one that supports the use of music creation itself as a tool for inquiry into music pedagogy. One such method is Eisner’s (1997) model of educational inquiry by means of connoisseurship and criticism. Connoisseurship is the “ability to make fine-grained discriminations among complex and subtle qualities” (Eisner 1997, 63). Criticism is judgment that illuminates and interprets the qualities of a practice in order to transform it. As a subjective researcher, I am obliged to systematically identify my subjectivity (Peshkin, 1988), and I view my role as connoisseur and critic in music as a source of clarity rather than bias.

Ethnography

An interpretivist paradigm is well supported by methods of ethnography, since participant observation and unstructured interviews dovetail exactly with a subjectivist epistemology. Ethnographers typically allow their methods to evolve over the course of the study, and can only define their procedures in retrospect, in the form of a narrative of what actually happened, rather than a detailed plan ahead of time. This form of research is iterative, like agile software development. Data comes in the form of interpretations of interpretations of interpretations, and in that sense is a “fiction”—not in the sense that it is counterfactual (we hope), but in the original sense of the word, a thing that is constructed. We must involve our imagination in constructing our interpretive fictions (Geertz, 1973).

Institutional ethnographers examine work settings and processes, combining observation with discourse analysis of texts, documents and procedures. The goal is to show how people in the workplace align their activities with structures that may originate elsewhere (Devault, 2006). This method asks us to seek out “ruling relations” (Smith 2005, 11), textually mediated connections and organizations shaping everyday life, especially those that are the most taken for granted. In so doing, we examine the ways that texts bind small social groups into institutions, and bind those together into larger power structures. This method is well suited to a profession like music teaching.

Taber (2010) combines autoethnography with institutional ethnography to tell the story of her own experience in the military, as an entry point into understanding the experience of other women. She questions whether researching the lives of others was a way to hide from her own problematic experience, and chooses instead to foreground her internal conflicts, using a “reflexivity of discomfort” (19). This is emblematic of the institutional ethnographic practice of examining aspects of organizations that their inhabitants find problematic, troubling or contradictory. Since the story of my own music education is one of internal conflict and discomfort, I expect a similar method to Taber’s to yield rich results.

Naturally, an inquiry into music education will involve some ethnomusicology. Given how technologically mediated hip-hop and other contemporary forms are, it will be useful to take on the lens of “technomusicology” (Marshall, 2017). Music educators who feel pressured to use computers in their practice quickly run up against the fact that digital audio tools are a poor fit for classical music. However, these tools are the most natural medium for hip-hop and other electronic dance musics. The technological and cultural issues are inseparable.

Hip-hop grows out orality and African-American Vernacular English. Therefore, it is prone to being dismissed by scholars working in a literate value system. Similarly, it is all too common to view AAVE through the lens of deprivationism, as a failure to learn “correct” English. To overcome this spurious attitude, we can employ an ethnopoetic approach. Speakers of AAVE are only linguistically “impoverished” because we institutionally deem them to be so, not because they have any difficulty communicating or expressing themselves (McDermott & Varenne, 1995). By the same token, classical music culture sees the lack of complex harmony and melody in African diasporic music like hip-hop as a shortcoming, a poverty of musical means. But the hip-hop aesthetic puts a premium on rhythm and timbre, and harmony functions mostly as a way to signpost locations within the cyclical metrical structure. In learning to value hip-hop on its own terms, we broaden our ability to understand other musical and cultural value systems as well.

Participatory research

Participatory research methods like cooperative inquiry and participatory action research treat research participants as collaborators, rather than as objects of study. The related method of constructivist instructional design puts these principles into action in the form of new technologies, experiences and curricula, the educational equivalent of critical theorists’ activism. When teachers and designers act as researchers, they function as participant observers. While I am an avid hip-hop fan and a dedicated student of it, I am ultimately a tourist. My research will therefore necessarily be incomplete unless it is a collaborative effort with members of hip-hop culture.

Instructional design as participatory research follows a Reflective and Recursive Design and Development (R2D2) model, based on the principles of recursion, nonlinearity and reflection (Willis, 2007). Designers test and prototype continually alongside users, and feed the results back into the next design iteration. This process for developing instructional material enables end users and experts to work jointly toward the end product. This loop of feedback and iteration is an example of reflective practice, made up of the “arts” of problem framing, implementation, and improvisation (Schön, 1987). These same arts are the ones used in musical problem-solving, both as a practitioner and educator. The Music Experience Design Lab follows a participatory design methodology in developing our technologies for music learning and expression, and the idea of using the same techniques to examine the broader social context of our work is quite appealing to me.

Narrative inquiry

There may be universal physical truths, but mental, emotional and social truths are contextual and particular. To examine these truths, then, we need verstehen, understanding of context, both historical and contemporary (Willis, 2007). To that end, we can draw on phenomenology, asking how humans view themselves and the world around them. This perspective attends to experience “from the neck down,” not just to cognition. We need to understand the bodily sensations of numbness, anxiety or anger that too many students feel in the music classroom, knowing that something is wrong but not knowing how to name it. For example, I spent my music graduate theory seminar in a continual low boil of rage, and it was only years later that I was able to point to the white supremacist ideology animating the curriculum as the source of this intense emotion. A number of my fellow musicians aligned with black music have described the same feelings. It is a primary research goal of mine to give those feelings a name and a clear target, so they can be put to work in the service of systemic change.

Bruner (1991) cites Vygotsky’s dictum that cultural products like language mediate our thought and shape our representations of reality. (This is certainly true of music.) Constructionists assume that we produce reality through the social exchange of meanings. We use language not as isolated individuals, but within social groups, organizations, institutions and cultures. Within our contexts, we speak as we understand it to be appropriate to speak (Galasinski & Ziólkowska, 2013). As narratives accrue into traditions, they take on a life of their own that can outlive their original context—this is a likely explanation for the persistence of classical music habitus far beyond the conservatory.

Close readers of narrative must study not only the syntactic content of the words themselves, but also their literary qualities, their tone (Riessman, 2008). There is a close parallel here with musicology. When we compare Julie Andrews’ performance of “My Favorite Things” in The Sound Of Music (1965) with the one recorded by John Coltrane (1961), it is like comparing the same text spoken by two very different speakers. We can perform a neat inverse of this process by examining the same musical performance across contexts; for example, comparing Tom Scott’s recording of Balin and Kantner’s “Today” (1967) with the sample of that recording that forms the centerpiece of Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth’s “They Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.)” (1992). Here, the same performance gives rise to different musical meanings in different settings. We should be similarly attentive to the performative and contextual aspects of narrative.

Validity and reliability

If we are examining attitudes and interpretations rather than more easily observable “facts,” how do we ensure validity and reliability? In place of a search for straightforward logical explanations, we can instead build a case on Lyotardian paralogy, and “let contradictions remain in tension” (Lather 1993, 679), like the unresolved tritones enriching the blues and jazz. We should not expect to find tree-shaped hierarchies of explanation, but instead hold ourselves to a “rhizomatic” standard of validity. “Rather than a linear progress, rhizomatics is a journey among intersections, nodes, and regionalizations through a multi-centered complexity” (Lather 1993, 680). We can understand the complexities of music and schooling and race to have the topology of a network, not a tree. We should expect that when we pull on any part of the network, we will encounter a tangle.

In my research thus far, I have instinctively used reciprocity to treat my interviews more as two-way conversations. Such judicious use of self-disclosure can give rise to richer data. We can attain further reciprocity by showing participants field notes and drafts, building in “member checks” early on to ensure trustworthiness throughout the process. As feminist researchers, Harrison, MacGibbon and Morton (2001) hold attention to emotional aspects of the research and the relationships it entails as a key criterion of trustworthiness. This kind of emotionally aware collaborative/shared authorship aligns naturally with participatory research, and with hip-hop pedagogy. Larson (1997) argues that narrative inquiry gains greater validity by having the story-giver reflect on the transcript and analysis so they can revise or go deeper into their story. If a lived experience is an iceberg, then its initial retelling may just describe the tip. It takes reflection to bring more of the iceberg to the surface. We may therefore do better to examine a few icebergs thoroughly than to survey many tips.

Sample data and future research

Ed Sullivan Fellows (ESF) is a mentorship and artist development program run by the NYU Steinhardt Music Experience Design Lab. Participants are young men and women between the ages of 15 and 20, mostly low-SES people of color. They meet on Saturday afternoons at NYU to write and record songs; to get mentorship on the music business, marketing and branding; and to socialize. Sessions have a clubhouse feel, a series of ad-hoc jam sessions, cyphers, informal talks, and open-ended creativity. Conversations are as likely to focus on participants’ emotions, politics, social life and identity as they are on anything pertaining to music. I intend to conduct my research among hip-hop educators like Jamie and the other ESF mentors. They teach music concepts like song structure and harmony, but their project is much larger: to provide emotional support, to build resilience and confidence, to foster social connections across class and racial lines. Hein (2017) is a set of preliminary observations on ESF, showing the close connection between its musical and social values.

Conclusion

If music education is failing to address the needs of the substantial majority of students, it should be no wonder that enrollment and societal support are declining.

Every ‘failure’ to succeed in competition, every drop-out, and every student who is relieved to have compulsory music study behind them (including lessons enforced by parental fiat) represents not just a lack of ‘conversion’ to musical ‘virtue’ but gives such future members of the public compelling reason to doubt whether their music education has served any lasting purpose or value (Regelski 2009, 12).

Music educators’ advocacy efforts are mostly devoted to preserving existing methods and policies. However, these same methods and practices are driving music education’s irrelevance. At some point, advocacy starts to look less like a high-minded push for society’s interest, and more like an effort on behalf of music teachers’ self-interest.

Most (if not all) people have an inborn capacity and intrinsic motivation for engaging in music. However, that capacity and motivation need to be activated and nurtured by “musically and educationally excellent teachers and… inspiring models of musicing in contexts of welcoming, sustaining, and educative musical settings, including home and community contexts” (Elliott & Silverman 2015, 240). To restrict this opportunity to “talented” students is anti-democratic in Dewey’s sense. Good music serves particular human needs. One of those needs is aesthetic contemplation and appreciation of the Eurocentric canon. But there are many other legitimate ends that music education can pursue. In order to meet more students’ musical needs, we must embrace the musical culture of the present, and confront all the challenges of race and class that entails.

References

Anyon, J. (1980). Social Class and the Hidden Curriculum of Work. The Journal of Education, 162(1), 67–92.

Bell, A. P. (2014). Trial-by-fire : A case study of the musician – engineer hybrid role in the home studio. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 7(3), 295–312.

Bledsoe, R. (2015). Music Education for All? General Music Today, 28(2), 18–22.

Bowman, W. (2007). Who is the “We”? Rethinking Professionalism in Music Education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 6(4), 109–131.

Bowman, W. (2016). Artistry, Ethics, and Citizenship. In D. Elliott, M. Silverman, & W. Bowman (Eds.), Artistic Citizenship: Artistry, Social Responsibility, and Ethical Praxis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, P. S., Connell, C., & Beegle, A. (2007). Adolescents’ expressed meanings of music in and out of school. Journal of Research in Music Education, 55(3), 220–236.

Cutler, C. (2004). Plunderphonia. In C. Cox & D. Warner (Eds.), Audio culture: Readings in modern music (pp. 138–156). London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

DeNora, T. (2000). Music in everyday life. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Devault, M. L. (2006). Introduction: What is Institutional Ethnography? Social Problems, 53(3), 294–298.

Dillon, S. (2007). Music, Meaning and Transformation: Meaningful Music Making for Life. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Doyle, J. L. (2014). Cultural relevance in urban music education: a synthesis of the literature. Applications of Research in Music Education, 32(2), 44–51.

Eisner, E. (1991). The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and the enhancement of educational practice. Toronto: Macmillan.

Elliott, D. J., & Silverman, M. (2014). Music Matters: A Philosophy of Music Education (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elpus, K., & Abril, C. R. (2011). High School Music Ensemble Students in the United States: A Demographic Profile. Journal of Research in Music Education, 59(2), 128–145.

Eno, B. (2004). The Studio As Compositional Tool. In C. Cox & D. Warner (Eds.), Audio culture: Readings in modern music (pp. 127–130). London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Ester, D. P., & Turner, K. (2009). The impact of a school loaner-instrument program on the attitudes and achievement of low-income music students. Contributions to Music Education, 36(1), 53–71.

Finney, J. (2007). Music Education as Identity Project in a World of Electronic Desires. In J. Finney & P. Burnard (Eds.), Music education with digital technology. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Harrison, J., MacGibbon, L., & Morton, M. (2001). Regimes of Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research: The Rigors of Reciprocity. Qualitative Inquiry, 7(3), 323–345.

Hein, E. (2015). Mad Fresh. NewMusicBox. Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.newmusicbox.org/articles/mad-fresh/

Hein, E. (2017). A participant ethnography of the Ed Sullivan Fellows program. Retrieved May 9, 2017, from http://www.ethanhein.com/wp/2017/a-participant-ethnography-of-the-ed-sullivan-fellows-program/

Irby, D. J., & Hall, H. B. (2011). Fresh Faces, New Places: Moving Beyond Teacher-Researcher Perspectives in Hip-Hop-Based Education Research. Urban Education, 46(2), 216–240.

Kratus, J. (2016). Songwriting: A new direction for secondary music education. Music Educators Journal, 102(3), 60–65.

Kratus, J. (2007). Music Education at the Tipping Point. Music Educators Journal, 94(2), 42–48.

Kruse, A. J. (2016). Toward hip-hop pedagogies for music education. International Journal of Music Education, 34(2), 247–260.

Laitz, S. G. (2015). The complete musician: An integrated approach to tonal theory, analysis, and listening (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Lather, P. (1993). Fertile Obsession : Validity after Poststructuralism. The Sociological Quarterly, 34(4), 673–693.

Lorde, A. (1984). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde, 110–113.

Luker, K. (2008). Salsa Dancing into the Social Sciences : Research in an Age of Info-glut. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Madrid, A. L. (2017). Diversity, Tokenism, Non-Canonical Musics, and the Crisis of the Humanities in U.S. Academia, 7(2), 124–129.

Marshall, W. (2017). Technomusicology | Harvard Extension School. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.extension.harvard.edu/academics/courses/technomusicology/24318

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid : segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mcclary, S. (2000). Conventional Wisdom: The Content of Musical Form. University of California Press.

McDermott, R., & Varenne, H. (1995). Culture as Disability. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 26(3), 324–348.

Miles, J., Hogan, E., Boland, B., Ehrenfeld, J., & Berry, L. (2015). Fresh Ed: A Field Guide to Culturally Responsive Pedagogy. New York: Urban Arts Partnership. Retrieved from http://freshed.urbanarts.org/fresh-field-guide/

Perry, I. (2004). Prophets of the Hood. Duke University Press.

Peshkin, A. (1988). In Search of Subjectivity–One’ s Own. Educational Researcher, 17–21.

Pomykala-Hein, M. (2017). Searching [Online musical score]. Retrieved May 5, 2017, from https://www.noteflight.com/scores/view/180d4db69af3646e6e70fae8002648d7f2048a7d

Regelski, T. A. (2009). The Ethics of Music Teaching as Profession and Praxis. Visions of Research in Music Education, 13(2009), 1–34.

Rice, J. (2016). The 1963 hip-hop machine: Hip-hop pedagogy as composition. College Composition and Communication, 54(3), 453–471.

Ruthmann, A. (2007). The Composers’ Workshop: An Approach to Composing in the Classroom. Music Educators Journal, 93(4), 38.

Schön, D. (1987). Teaching artistry through reflection in action. In Educating the reflective practitioner: Educating the reflective practitioner for teaching and learning in the professions (pp. 22–40). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sennett, R. (2008). The Craftsman (New Haven). Yale University Press.

Smith, D. (2005). Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Taber, N. (2010). Institutional ethnography, autoethnography, and narrative: an argument for incorporating multiple methodologies. Qualitative Research, 10(1), 5–25. http://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109348680

Thibeault, M. (2010). Hip-Hop, Digital Media, and the Changing Face of Music Education. General Music Today, 24(1), 46–49. http://doi.org/10.1177/1048371310379097

Turino, T. (2016). Music, Social Change, and Alternative Forms of Citizenship. In D. Elliott, M. Silverman, & W. Bowman (Eds.), Artistic Citizenship: Artistry, Social Responsibility, and Ethical Praxis (p. 616). New York: Oxford University Press.

van der Schyff, D., Schiavio, A., & Elliott, D. J. (2016). Critical ontology for an enactive music pedagogy. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 15(5), 81–121.

Williams, D. A. (2011). The Elephant in the Room. Music Education: Navigating the Future, 98(1), 51–57.

Willis, J. W. (2007). Foundations of Qualitative Research: Interpretive and Critical Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wise, R. (1965). The Sound Of Music. United States: 20th Century Fox.

Discography

Balin, M. and Kantner, P. (1967). Today [recorded by Tom Scott and The California Dreamers]. On The Honeysuckle Breeze [LP]. Santa Monica: Impulse! (1967)

Elliott, Missy (2002). Work It. On Under Construction [CD]. New York: Goldmind/Elektra. (November 12, 2002)

Lamar, Kendrick (2017). Pride. On DAMN. [CD/streaming]. Santa Monica, CA: Top Dawg/Aftermath/Interscope. (April 14, 2017)

Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth (1992). They Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.). On Mecca and the Soul Brother [LP]. New York: Untouchables/Elektra. (April 2, 1992)

Rodgers, Richard and Hammerstein, Oscar (1959). My Favorite Things [recorded by John Coltrane]. On My Favorite Things [LP]. New York: Atlantic. (March, 1961)