The hippest music teachers help their students create original music. But what exactly does that mean? What even is composition? In this post, I take a look at two innovators in music education and try to arrive at an answer.

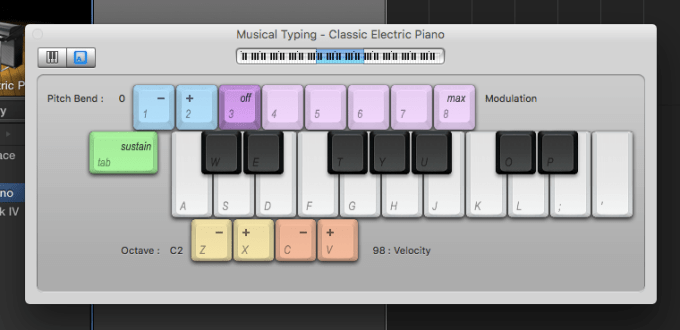

Matt McLean is the founder of the amazing Young Composers and Improvisers Workshop. He teaches his students composition using a combination of Noteflight, an online notation editor, and the MusEDLab‘s own aQWERTYon, a web app that turns your regular computer keyboard into an intuitive musical interface.

Participating students in YCIW as well as my own students at LREI have been using Noteflight for over 6 years to compose music for chamber orchestras, symphony orchestras, jazz ensembles, movie soundtracks, video game music, school band and more – hundreds of compositions.

Before the advent of the aQWERTYon, students needed to enter music into Noteflight either by clicking with the mouse or by playing notes in with a MIDI keyboard. The former method is accessible but slow; the latter method is fast but requires some keyboard technique. The aQWERTYon combines the accessibility of the mouse with the immediacy of the piano keyboard.

For the first time there is a viable way for every student to generate and notate her ideas in a tactile manner with an instrument that can be played by all. We founded Young Composers & Improvisors Workshop so that every student can have the experience of composing original music. Much of my time has been spent exploring ways to emphasize the “experiencing” part of this endeavor. Students had previously learned parts of their composition on instruments after their piece was completed. Also, students with piano or guitar skills could work out their ideas prior to notating them. But efforts to incorporate MIDI keyboards or other interfaces with Noteflight in order to give students a way to perform their ideas into notation always fell short.

The aQWERTYon lets novices try out ideas the way that more experienced musicians do: by improvising with an instrument and reacting to the sounds intuitively. It’s possible to compose without using an instrument at all, using a kind of sudoku-solving method, but it’s not likely to yield good results. Your analytical consciousness, the part of your mind that can write notation, is also its slowest and dumbest part. You really need your emotions, your ear, and your motor cortex involved. Before computers, you needed considerable technical expertise to be able to improvise musical ideas, and remember them long enough to write them down. The advent of recording and MIDI removed a lot of the friction from the notation step, because you could preserve your ideas just by playing them. With the aQWERTYon and interfaces like it, you can do your improvisation before learning any instrumental technique at all.

Student feedback suggests that kids like being able to play along to previously notated parts as a way to find new parts to add to their composition. As a teacher I am curious to measure the effect of students being able to practice their ideas at home using aQWERTYon and then sharing their performances before using their idea in their composition. It is likely that this will create a stronger connection between the composer and her musical idea than if she had only notated it first.

Those of us who have been making original music in DAWs are familiar with the pleasures of creating ideas through playful jamming. It feels like a major advance to put that experience in the hands of elementary school students.

Matt uses progressive methods to teach a traditional kind of musical expression: writing notated scores that will then be performed live by instrumentalists. Matt’s kids are using futuristic tools, but the model for their compositional technique is the one established in the era of Beethoven.

(I just now noticed that the manuscript Beethoven is holding in this painting is in the key of D-sharp. That’s a tough key to read!)

Other models of composition exist. There’s the Lennon and McCartney method, which doesn’t involve any music notation. Like most untrained rock musicians, the Beatles worked from lyric sheets with chords written on them as a mnemonic. The “lyrics plus chords” method continues to be the standard for rock, folk and country musicians. It’s a notation system that’s only really useful if you already have a good idea of how the song is supposed to sound.

Lennon and McCartney originally wrote their songs to be performed live for an audience. They played in clubs for several years before ever entering a recording studio. As their career progressed, however, the Beatles stopped performing live, and began writing with the specific goal of creating studio recordings. Some of those later Beatles tunes would be difficult or impossible to perform live. Contemporary artists like Missy Elliott and Pharrell Williams have pushed the Beatles’ idea to its logical extreme: songs existing entirely within the computer as sequences of samples and software synths, with improvised vocals arranged into shape after being recorded. For Missy and Pharrell, creating the score and the finished recording are one and the same act.

Is it possible to teach the Missy and Pharrell method in the classroom? Alex Ruthmann, MusEDLab founder and my soon-to-be PhD advisor, documented his method for doing so in 2007.

As a middle school general music teacher, I’ve often wrestled with how to engage my students in meaningful composing experiences. Many of the approaches I’d read about seemed disconnected from the real-world musicality I saw daily in the music my students created at home and what they did in my classes. This disconnect prompted me to look for ways of bridging the gap’ between the students’ musical world outside music class and their in-class composing experiences.

It’s an axiom of constructivist music education that students will be most motivated to learn music that’s personally meaningful to them. There are kids out there for whom notated music performed on instruments is personally meaningful. But the musical world outside music class usually follows the Missy and Pharrell method.

[T]he majority of approaches to teaching music with technology center around notating musical ideas and are often rooted in European classical notions of composing (for example, creating ABA pieces, or restricting composing tasks to predetermined rhythmic values). These approaches require students to have a fairly sophisticated knowledge of standard music notation and a fluency working with rhythms and pitches before being able to explore and express their musical ideas through broader musical dimensions like form, texture, mood, and style.

Noteflight imposes some limitations on these musical dimensions. Some forms, textures, moods and styles are difficult to capture in standard notation. Some are impossible. If you want to specify a particular drum machine sound combined with a sampled breakbeat, or an ambient synth pad, or a particular stereo image, standard notation is not the right tool for the job.

Common approaches to organizing composing experiences with synthesizers and software often focus on simplified classical forms without regard to whether these forms are authentic to the genre or to technologies chosen as a medium for creation.

There is nothing wrong with teaching classical forms. But when making music with computers, the best results come from making the music that’s idiomatic to computers. Matt McLean goes to extraordinary lengths to have student compositions performed by professional musicians, but most kids will be confined to the sounds made by the computer itself. Classical forms and idioms sound awkward at best when played by the computer, but electronic music sounds terrific.

The middle school students enrolled in these classes came without much interest in performing, working with notation, or studying the classical music canon. Many saw themselves as “failed” musicians, placed in a general music class because they had not succeeded in or desired to continue with traditional performance-based music classes. Though they no longer had the desire to perform in traditional school ensembles, they were excited about having the opportunity to create music that might be personally meaningful to them.

Here it is, the story of my life as a music student. Too bad I didn’t go to Alex’s school.

How could I teach so that composing for personal expression could be a transformative experience for students? How could I let the voices and needs of the students guide lessons for the composition process? How could I draw on the deep, complex musical understandings that these students brought to class to help them develop as musicians and composers? What tools could I use to quickly engage them in organizing sound in musical and meaningful ways?

Alex draws parallels between writing music and writing English. Both are usually done alone at a computer, and both pose a combination of technical and creative challenges.

Musical thinking (thinking in sound) and linguistic thinking (thinking using language phrases and ideas) are personal creative processes, yet both occur within social and cultural contexts. Noting these parallels, I began to think about connections between the whole-language approach to writing used by language arts teachers in my school and approaches I might take in my music classroom.

In the whole-language approach to writing, students work individually as they learn to write, yet are supported through collaborative scaffolding-support from their peers and the teacher. At the earliest stages, students tell their stories and attempt to write them down using pictures, drawings, and invented notation. Students write about topics that are personally meaningful to them, learning from their own writing and from the writing of their peers, their teacher, and their families. They also study literature of published authors. Classes that take this approach to teaching writing are often referred to as “writers’ workshops”… The teacher facilitates [students’] growth as writers through minilessons, share sessions, and conferring sessions tailored to meet the needs that emerge as the writers progress in their work. Students’ original ideas and writings often become an important component of the curriculum. However, students in these settings do not spend their entire class time “freewriting.” There are also opportunities for students to share writing in progress and get feedback and support from teacher and peers. Revision and extension of students’ writing occur throughout the process. Lessons are not organized by uniform, prescriptive assignments, but rather are tailored to the students’ interests and needs. In this way, the direction of the curriculum and successive projects are informed by the students’ needs as developing writers.

Alex set about creating an equivalent “composers’ workshop,” combining composition, improvisation, and performing with analytical listening and genre studies.

The broad curricular goal of the composers’ workshop is to engage students collaboratively in:

- Organizing and expressing musical ideas and feelings through sound with real-world, authentic reasons for and means of composing

- Listening to and analyzing musical works appropriate to students’ interests and experiences, drawn from a broad spectrum of sources

- Studying processes of experienced music creators through listening to, performing, and analyzing their music, as well as being informed by accounts of the composition process written by these creators.

Alex recommends production software with strong loop libraries so students can make high-level musical decisions with “real” sounds immediately.

While students do not initially work directly with rhythms and pitch, working with loops enables students to begin composing through working with several broad musical dimensions, including texture, form, mood, and affect. As our semester progresses, students begin to add their own original melodies and musical ideas to their loop-based compositions through work with synthesizers and voices.

As they listen to musical exemplars, I try to have students listen for the musical decisions and understand the processes that artists, sound engineers, and producers make when crafting their pieces. These listening experiences often open the door to further dialogue on and study of the multiplicity of musical roles’ that are a part of creating today’s popular music. Having students read accounts of the steps that audio engineers, producers, songwriters, film-score composers, and studio musicians go through when creating music has proven to be informative and has helped students learn the skills for more accurately expressing the musical ideas they have in their heads.

Alex shares my belief in project-based music technology teaching. Rather than walking through the software feature-by-feature, he plunges students directly into a creative challenge, trusting them to pick up the necessary software functionality as they go. Rather than tightly prescribe creative approaches, Alex observes the students’ explorations and uses them as opportunities to ask questions.

I often ask students about their composing and their musical intentions to better understand how they create and what meanings they’re constructing and expressing through their compositions. Insights drawn from these initial dialogues help me identify strategies I can use to guide their future composing and also help me identify listening experiences that might support their work or techniques they might use to achieve their musical ideas.

Some musical challenges are more structured–Alex does “genre studies” where students have to pick out the qualities that define techno or rock or film scores, and then create using those idioms. This is especially useful for younger students who may not have a lot of experience listening closely to a wide range of music.

Rather than devoting entire classes to demonstrations or lectures, Alex prefers to devote the bulk of classroom time to working on the projects, offering “minilessons” to smaller groups or individuals as the need arises.

Teaching through minilessons targeted to individuals or small groups of students has helped to maintain the musical flow of students’ compositional work. As a result, I can provide more individual feedback and support to students as they compose. The students themselves also offer their own minilessons to peers when they have designed to teach more about advanced features of the software, such as how to record a vocal track, add a fade-in or fade-out, or copy their musical material. These technology skills are taught directly to a few students, who then become the experts in that skill, responsible for teaching other students in the class who need the skill.

Not only does the peer-to-peer learning help with cultural authenticity, but it also gives students invaluable experience with the role of teacher.

One of my first questions is usually, “Is there anything that you would like me to listen for or know about before I listen?” This provides an opportunity for students to seek my help with particular aspects of their composing process. After listening to their compositions, I share my impressions of what I hear and offer my perspective on how to solve their musical problems. If students choose not to accept my ideas, that’s fine; after all, it’s their composition and personal expression… Use of conferring by both teacher and students fosters a culture of collaboration and helps students develop skills in peer scaffolding.

Alex recommends creating an online gallery of class compositions. This has become easier to implement since 2007 with the explosion of blog platforms like Tumblr, audio hosting tools like SoundCloud, and video hosts like YouTube. There are always going to be privacy considerations with such platforms, but there is no shortage of options to choose from.

Once a work is online, students can listen to and comment on these compositions at home outside of class time. Sometimes students post pieces in progress, but for the most part, works are posted when deemed “finished” by the composer. The online gallery can also be set up so students can hear works written by participants in other classes. Students are encouraged to listen to pieces published online for ideas to further their own work, to make comments, and to share these works with their friends and family. The realworld publishing of students’ music on the Internet seems to contribute to their motivation.

Assessing creative work is always going to be a challenge, since there’s no objective basis to assess it on. Alex looks at how well a student composer has met the goal of the assignment, and how well they have achieved their own compositional intent.

The word “composition” is problematic in the context of contemporary computer-based production. It carries the cultural baggage of Western Europe, the idea of music as having a sole identifiable author (or authors.) The sampling and remixing ethos of hip-hop and electronica are closer to the traditions of non-European cultures where music may be owned by everyone and no one. I’ve had good results bringing remixing into the classroom, having students rework each others’ tracks, or beginning with a shared pool of audio samples, or doing more complex collaborative activities like musical shares. Remixes are a way of talking about music via the medium of music, and remixes of remixes can make for some rich and deep conversation. The word “composition” makes less sense in this context. I prefer the broader term “production”, which includes both the creation of new musical ideas and the realization of those ideas in sound.

So far in this post, I’ve presented notation-based composition and loop-based production as if they’re diametrical opposites. In reality, the two overlap, and can be easily combined. A student can create a part as a MIDI sequence and then convert it to notation, or vice versa. The school band or choir can perform alongside recorded or sequenced tracks. Instrumental or vocal performances can be recorded, sampled, and turned into new works. Electronic productions can be arranged for live instruments, and acoustic pieces can be reconceived as electronica. If a hip-hop track can incorporate a sample of Duke Ellington, there’s no reason that sample couldn’t be performed by a high school jazz band. The possibilities are endless.