Here’s what happened in my life as an educator this past semester, and what I have planned for the coming semester.

Montclair State University Intro To Music Technology

I wonder how much longer “music technology” is going to exist as a subject. They don’t teach “piano technology” or “violin technology.” It makes sense to teach specific areas like audio recording or synthesis or signal theory as separate classes. But “music technology” is such a broad term as to be meaningless. The unspoken assumption is that we’re teaching “musical practices involving a computer,” but even that is both too big and too small to structure a one-semester class around. On the one hand, every kind of music involves computers now. On the other hand, to focus just on the computer part is like teaching a word processing class that’s somehow separate from learning how to write.

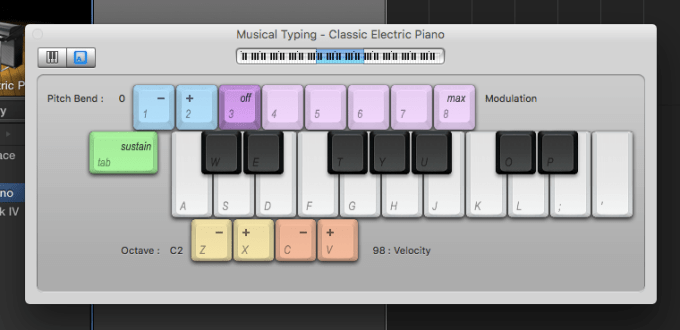

The newness and vagueness of the field of study gives me and my fellow music tech educators wide latitude to define our subject matter. I see my job as providing an introduction to pop production and songwriting. The tools we use for the job at Montclair are mostly GarageBand and Logic, but I don’t spend a lot of time on the mechanics of the software itself. Instead, I teach music: How do you express yourself creatively using sample libraries, or MIDI, or field recordings, or pre-existing songs? What kinds of rhythms, harmonies, timbres and structures make sense aesthetically when you’re assembling these materials in the DAW? Where do you get ideas? How do you listen to recorded music analytically? Why does Thriller sound so much better than any other album recorded in the eighties? We cover technical concepts as they arise in the natural course of producing and listening. My hope is that they’ll be more relevant and memorable that way.

Having now taught three semesters of Intro to Music Tech at MSU, my format is starting to gel. The students spend most of the semester creating tracks. They do one using only the loops that come with GarageBand, one using only MIDI and software instruments, one that includes a field recording they made with their phones, and so on. I started having them remix each other’s tracks this past semester, and it was such a smash hit that I’m going to have future classes do a whole series of peer remixes.

Montclair is a fairly traditional conservatory. For many students, my class is the only time in their college careers they get to make music according to their own sensibilities and tastes. It’s also usually the only time they engage critically with recordings, or electronic dance music, or hip-hop, or pop song forms, or sampling, or mixing and audio processing. I’m glad to be able to fill these vacuums, but I wish I had more than one semester to do it in.

Aside from creative music-making, the students do a couple of presentations, one on a song they think is interesting, and one on a topic of their choice. They also write blog posts about the process of creating their tracks. This last assignment is a persistent obstacle, since no one seems to share my enthusiasm for process documentation. Next semester I’m going to try introducing some of the cooperative/competitive spirit of the peer remixes by having them write reviews of each other’s tracks. Maybe that will get them to invest their writing with the same creativity they put into the music assignments.

Montclair State Advanced Computer Music Composition

This past fall I got to teach my first advanced class, and it went amazingly well. We used Ableton Live, my DAW of choice, and the guys (it was all guys) banged out tracks at a rapid clip for the entire semester. As with the intro class, I spent most of the time on the creative process, and dealt with Ableton functionality and audio engineering topics as they came up.

Each assignment came with some kind of tight technical restriction, but no stylistic restrictions. As with the intro class, the advanced dudes did tracks using only existing loops, only MIDI, and found sound. They did peer remixing and self remixing as well. The two hardest and most interesting assignments were to create a new track using only samples of an existing track, and then to create a new track using only a single five-second Duke Ellington sample. (These assignments were inspired heavily by the Disquiet Junto.) The more tightly I constrained the students, the more ingenuity they displayed. Listen for yourself:

As with the intro class, I tried to have the advanced dudes document their process with blog posts. As with the intro class, they showed zero interest. In the future, I’ll have to get more creative with the writing component. Also, I’d like to not have the class be entirely male.

NYU Music Education Technology Practicum

This class is meant to be a grounding in music tech for future music teachers. I’m even more time-constrained at NYU than at Montclair, and I teach in a regular classroom rather than a computer lab. While my class time at Montclair is mostly devoted to music-making, at NYU I’m forced to do more lectures, demos and listening sessions. It is very far from ideal. I have no idea how NYU can charge so much money without offering such a basic-seeming amenity as a room with computers in it for the music students. However, NYU does have one advantage over Montclair as a teaching environment, which is that I can hold a couple of class sessions in an extremely fancy recording studio.

I mostly take the same approach at NYU as I do at Montclair, and use most of the same assignments. The major difference is that the NYU kids do a critical listening project, where they pick a recording and graph out its musical structure and spatial layout. It’s a difficult exercise, but an invaluable one. I did it in grad school, and it improved my analytical listening abilities significantly. We used to do the same assignment at Montclair, but the students were really not into it, like to the point of refusing to do it, so sadly we had to drop it from the syllabus. I hope we can find a way to reinstate it.

This past semester, the majority of my NYU kids were music business majors, which was pretty great. They came in with less musical experience than the education majors–sometimes with none at all–but they had less to unlearn, and they threw themselves confidently into producing tracks. This coming semester I have a bunch more music business kids. I’m attracting them because my class is the only one at Steinhardt that does intro-level creative music making in the pop idiom. I’m clearly filling a vacuum, and I’m hoping that I’m just the thin edge of the wedge, both for my own sake and the future music educators of NYU.

Interface designs

The NYU Music Experience Design Lab is baking education into a suite of creative music making and learning tools. As my friend and colleague Adam Bell likes to say, purchasers of a computer are purchasing a music education. We’re trying to make that education a better and more enjoyable one, whether our users are in formal classroom settings or playing around on their own. You can read about the lab’s various projects here. My own contributions are largely conceptual, though I’ve also devoted a lot of attention to making useful and inspiring presets.

This winter, the MusEDLab is launching a brand new initiative, mentoring a group of young people from challenging circumstances in music and technology. I’ll be teaching the music side, doing a custom-tailored version of my intro class syllabus. Sullivan Fellows will also work with my colleagues in the lab on programming and design projects. This summer, we’ll have a showcase event as part of the 2016 IMPACT Conference. The goal is to help the Fellows get launched in careers in music and/or technology. I’ll be writing a lot more about this in the coming weeks.

Online courses with Soundfly

The MusEDLab is working with a music ed startup on some new interactive online courses. The first is called Music Theory For Bedroom Producers, and we expect to launch next month. I wrote a lot of the materials, and am appearing in some videos. Soundfly has ace designers, animators and programmers, so expect a rich multimedia experience. More on this as it gets closer.

Everything else

For the past few years, I’ve been a teaching artist with NYU’s IMPACT workshop. Below, you can see some participants making beats on an iPad. The workshop is a crash course not just in music, but in theater, dance, video, and the intersection of all of the above. I’m still very much figuring out my role in the whole thing, but so is everyone involved.

I continue to teach private lessons, do freelance production and composition, do some consulting, write for online publications, and generally keep hustling for gigs. If you’d like to have me do any of these things, be in touch.