I was asked by Alison Armstrong to comment on this Time magazine op-ed by Todd Stoll, the vice president of education at Jazz at Lincoln Center. Before I do, let me give some context: Todd Stoll is a friend and colleague of Wynton Marsalis, and he shares some of Wynton’s ideas about music.

Wynton Marsalis has some strong views about jazz, its historical significance, and its present condition. He holds jazz to be “America’s classical music,” the highest achievement of our culture, and the sonic embodiment of our best democratic ideals. The man himself is a brilliant practitioner of the art form. I’ve had the pleasure of hearing him play live several times, and he’s always a riveting improvisor. However, his definition of the word “jazz” is a narrow one. For Wynton Marsalis, jazz history ends in about 1965, right before Herbie Hancock traded in his grand piano for a Fender Rhodes. All the developments after that–the introduction of funk, rock, pop, electronic music, and hip-hop– are bastardizations of the music.

Wynton Marsalis’ public stature has given his philosophy enormous weight, which has been a mixed bag for jazz culture. On the one hand, he has been a key force in getting jazz the institutional recognition that it was denied for too many years. On the other hand, the form of jazz that Wynton advocates for is a museum piece, a time capsule of the middle part of the twentieth century. When jazz gained the legitimacy of “classical music,” it also became burdened with classical music’s stuffiness, pedantry, and disconnection from the broader culture. As the more innovative jazz artists try to keep pace with the world, they can find themselves more hindered by Wynton than helped.

So, with all that in mind, let’s see what Todd Stoll has to say about the state of music education on America.

No Child Left Behind, the largest attempt at education reform in our nation’s history, resulted in a massive surge in the testing of our kids and an increased focus in “STEM” (science, technology, engineering and math). While well-meaning, this legislation precipitated a gradual and massive decline of students participating in music and arts classes, as test prep and remedial classes took precedence over a broader liberal arts education, and music education was often reduced, cut, or relegated to after school.

Testing culture is a Bad Thing, no question there.

Taken on face value, Every Student Succeeds bodes well for music education and the National Association for Music Education, which spent thousands of hours lobbying on behalf of music teachers everywhere. The new act removes “adequate yearly progress” benchmarks and includes music and arts as part of its definition of a “well-rounded education.” It also refers to time spent teaching music and arts as “protected time.”

That is a Good Thing.

Music and arts educators now have some leverage for increased funding, professional development, equipment, staffing, prioritized scheduling of classes, and a more solid foothold when budgets get tight and cuts are being discussed. I can almost hear the discussions—”We can’t cut a core class now, can we?” In other words, music is finally at the grown-ups table with subjects like science, math, social studies and language arts.

Yes! Great. But how did music get sent to the kids’ table in the first place? How did we come to regard it as a luxury, or worse, a frivolity? How do we learn to value it more highly, so the next time that a rage for quantitative assessment sweeps the federal government, we won’t go through the same cycle all over again?

Now that we’re at the table, we need a national conversation to redefine the depth and quality of the content we teach in our music classes. We need a paradigm shift in how we define outcomes in our music students. And we need to go beyond the right notes, precise rhythms, clear diction and unified phrasing that have set the standard for the past century.

True. The standard music curriculum in America is very much stuck in the model of the nineteenth century European conservatory. There’s so much more we could be doing to awaken kids’ innate musicality.

We should define learning by a student’s intimate knowledge of composers or artists—their personal history, conception and the breadth and scope of their output.

Sure! This sounds good.

Students should know the social and cultural landscape of the era in which any piece was written or recorded, and the circumstances that had an influence.

Stoll is referring here to the outdated notion of “absolute music,” the idea that the best music is “pure,” that it transcends the grubby world of politics and economics and fashion. We definitely want kids to know that music comes from a particular time and place, and that it responds to particular forces and pressures.

We should teach the triumphant mythology of our greatest artists—from Louis Armstrong to Leonard Bernstein, from Marian Anderson to Mary Lou Williams, and others.

Sure, students should know who black and female and Jewish musicians are. Apparently, however, our greatest artists all did their work before 1965.

Students should understand the style and conception of a composer or artist—what are the aesthetics of a specific piece, the notes that have meaning? They should know the influences and inputs that went into the creation of a piece and how to identify those.

Very good idea. I’m a strong believer in the evolutionary biology model of music history. Rather than doing a chronological plod through the Great Men (and now Women), I like the idea of picking a musical trope and tracing out its family tree.

There should be discussion of the definitive recording of a piece, and students should make qualitative judgments on such against a rubric defined by the teacher that easily and broadly gives definition and shape to any genre.

The Wynton Marsalis version of jazz has turned out to be a good fit for academic culture, because there are Canonical Works by Great Masters. In jazz, the canonical work is a recording rather than a score, but the scholarly approach can be the same. This model is problematic for an improvised, largely aural, and dance-oriented tradition like jazz, to say the least, but it is progress to be talking about recording as an art form unto itself.

Selected pieces should illuminate the general concepts of any genre—the 6/8 march, the blues, a lyrical art song, counterpoint, AABA form, or call and response—and students should be able to understand these and know their precise location within a score and what these concepts represent.

Okay. Why? I mean, these are all fine things to learn and teach. But they only become meaningful through use. A kid might rightly question whether their knowledge of lyrical art song or AABA form has anything to do with anything. Once a kid tries writing a song, these ideas suddenly become a lot more pertinent.

We should embrace the American arts as a full constituent in our programs—not the pop-tinged sounds of The Voice or Glee but our music: blues, folk, spirituals, jazz, hymns, country and bluegrass, the styles that created the fabric of our culture and concert works by composers who embraced them.

This is where Stoll and I part company. Classical pedagogues have earned a bad reputation for insisting that kids like the wrong music. Stoll is committing the same sin here. Remember, kids: Our Music is not your music. You are supposed to like blues, folk, spirituals, jazz, hymns, country and bluegrass. Those are the styles that created the fabric of our culture. And they inspired concert works by composers, so that really makes them legit. Music that was popular in your lifetime, or your parents’ lifetime, is suspect.

Students should learn that the written score is a starting point. It’s the entry into a world of discovery and aspiration that can transform their lives; it’s deeper than notes. We should help them realize that a lifetime of discovery in music is a worthwhile and enjoyable endeavor.

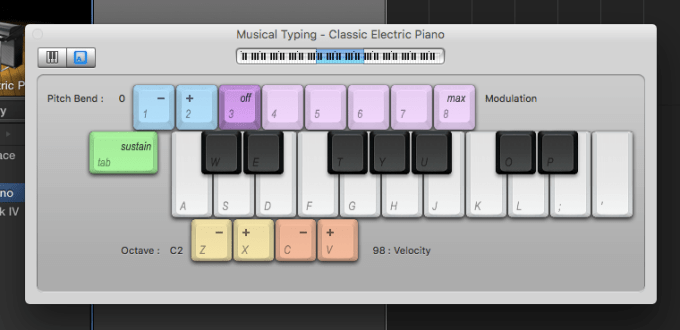

Score-centrism is a bad look from anyone, and it’s especially disappointing from a jazz guy. What does this statement mean to a kid immersed in rock or hip-hop, where nothing is written down? The score should be presented as what it is: one starting point among many. You can have a lifetime of discovery in music without ever reading a note. I believe that notation is worth teaching, but it’s worth teaching as a means to an end, not as an end unto itself.

These lessons will require new skills, extra work outside of class, more research, and perhaps new training standards for teachers. But, it’s not an insurmountable task, and it is vital, given the current strife of our national discourse.

If we can agree on the definitive recording of West Side Story, we can bridge the partisan divide!

Our arts can help us define who we are and tell us who we can be. They can bind the wounds of racism, compensate for the scourge of socio-economic disadvantage, and inoculate a new generation against the fear of not knowing and understanding those who are different from themselves.

I want this all to be true. But there is some magical thinking at work here, and magical thinking is not going to help us when budgets get cut. I want the kids to have the opportunity to study Leonard Bernstein and Marian Anderson. I’d happily toss standardized testing overboard to free up the time and resources. I believe that doing so will result in better academic outcomes. And I believe that music does make better citizens. But how does it do that? Saying that we need school music in order to instill Reverence for the Great Masters is weak sauce, even if the list of Great Masters now has some women and people of color on it. We need to be able to articulate specifically why music is of value to kids.

I believe that we have a good answer already: the point of music education should be to build emotionally stronger people. Done right, music promotes flow, deep attention, social bonding, and resilience. As Steve Dillon puts it, music is “a powerful weapon against depression.” Kids who are centered, focused, and able to regulate their moods are going to be better students, better citizens, and (most importantly!) happier humans. That is why it’s worth using finite school resources to teach music.

The question we need to ask is: what methods of music education best support emotional development in kids? I believe that the best approach is to treat every kid as a latent musician, and to help them develop as such, to make them producers rather than consumers. If a kid’s musicality can be nurtured best through studying jazz, great! That approach worked great for me, because my innermost musical self turns out to have a lot of resonance with Ellington and Coltrane. If a kid finds meaning in Beethoven, also great. But if the key to a particular kid’s lock is hip-hop or trance or country, music education should be equipped to support them too. Pointing young people to music they might otherwise miss out on is a good idea. Stifling them under the weight of a canon is not.