Ableton recently launched a delightful web site that teaches the basics of beatmaking, production and music theory using elegant interactives. If you’re interested in music education, creation, or user experience design, you owe it to yourself to try it out.

One of the site’s co-creators is Dennis DeSantis, who wrote Live’s unusually lucid documentation, and also their first book, a highly-recommended collection of strategies for music creation (not just in the electronic idiom.)

The other co-creator is Jack Schaedler, who also created this totally gorgeous interactive digital signal theory primer.

If you’ve been following the work of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, you might notice some strong similarities between Ableton’s site and our tools. That’s no coincidence. Dennis and I have been having an informal back and forth on the role of technology in music education for a few years now. It’s a relationship that’s going to get a step more formal this fall at the 2017 Loop Conference – more details on that as it develops.

Meanwhile, Peter Kirn’s review of the Learning Music site raises some probing questions about why Ableton might be getting involved in education in the first place. But first, he makes some broad statements about the state of the musical world that are worth repeating in full.

I think there’s a common myth that music production tools somehow take away from the need to understand music theory. I’d say exactly the opposite: they’re more demanding.

Every musician is now in the position of composer. You have an opportunity to arrange new sounds in new ways without any clear frame from the past. You’re now part of a community of listeners who have more access to traditions across geography and essentially from the dawn of time. In other words, there’s almost no choice too obvious.

The music education world has been slow to react to these new realities. We still think of composition as an elite and esoteric skill, one reserved only for small class of highly trained specialists. Before computers, this was a reasonable enough attitude to have, because it was mostly true. Not many of us can learn an instrument well enough to compose with it, then learn to notate our ideas. Even fewer of us will be able to find musicians to perform those compositions. But anyone with an iPhone and twenty dollars worth of apps can make original music using an infinite variety of sounds, and share that music online to anyone willing to listen. My kids started playing with iOS music apps when they were one year old. With the technical barriers to musical creativity falling away, the remaining challenge is gaining an understanding of music itself, how it works, why some things sound good and others don’t. This is the challenge that we as music educators are suddenly free to take up.

There’s an important question to ask here, though: why Ableton?

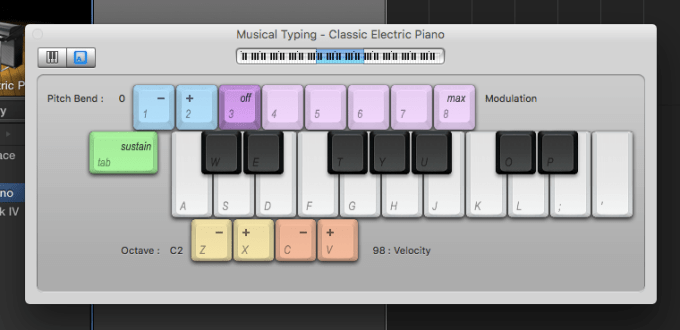

To me, the answer to this is self-evident. Ableton has been in the music education business since its founding. Like Adam Bell says, every piece of music creation software is a de facto education experience. Designers of DAWs might even be the most culturally impactful music educators of our time. Most popular music is made by self-taught producers, and a lot of that self-teaching consists of exploring DAWs like Ableton Live. The presets, factory sounds and affordances of your DAW powerfully inform your understanding of musical possibility. If DAW makers are going to be teaching the world’s producers, I’d prefer if they do it intentionally.

So far, there has been a divide between “serious” music making tools like Ableton Live and the toy-like iOS and web apps that my kids use. If you’re sufficiently motivated, you can integrate them all together, but it takes some skill. One of the most interesting features of Ableton’s web site, then, is that each interactive tool includes a link that will open up your little creation in a Live session. Peter Kirn shares my excitement about this feature.

There are plenty of interactive learning examples online, but I think that “export” feature – the ability to integrate with serious desktop features – represents a kind of breakthrough.

Ableton Live is a superb creation tool, but I’ve been hesitant to recommend it to beginner producers. The web site could change my mind about that.

So, this is all wonderful. But Kirn points out a dark side.

The richness of music knowledge is something we’ve received because of healthy music communities and music institutions, because of a network of overlapping ecosystems. And it’s important that many of these are independent. I think it’s great that software companies are getting into the action, and I hope they continue to do so. In fact, I think that’s one healthy part of the present ecosystem.

It’s the rest of the ecosystem that’s worrying – the one outside individual brands and what they support. Public music education is getting squeezed in different ways all around the world. Independent content production is, too, even in advertising-supported publications like this one, but more so in other spheres. Worse, I think education around music technology hasn’t even begun to be reconciled with traditional music education – in the sense that people with specialties in one field tend not to have any understanding of the other. And right now, we need both – and both are getting their resources squeezed.

This might feel like I’m going on a tangent, but if your DAW has to teach you how harmony works, it’s worth asking the question – did some other part of the system break down?

Yes it did! Sure, you can learn the fundamentals of rhythm, harmony, and form from any of a thousand schools, courses, or books. But there aren’t many places you can go to learn about it in the context of Beyoncé, Daft Punk, or A Tribe Called Quest. Not many educators are hip enough to include the Sleng Teng riddim as one of the fundamentals. I’m doing my best to rectify this imbalance–that’s what my courses with Soundfly classes are for. But I join Peter Kirn in wondering why it’s left to private companies to do this work. Why isn’t school music more culturally relevant? Why do so many educators insist that you kids like the wrong music? Why is it so common to get a music degree without ever writing a song? Why is the chasm between the culture of school music and music generally so wide?

Like Kirn, I’m distressed that school music programs are getting their budgets cut. But there’s a reason that’s happening, and it isn’t that politicians and school boards are philistines. Enrollment in school music is declining in places where the budgets aren’t being cut, and even where schools are offering free instruments. We need to look at the content of school music itself to see why it’s driving kids away. Both the content of school music programs and the people teaching them are whiter than the student population. Even white kids are likely to be alienated from a Eurocentric curriculum that doesn’t reflect America’s increasingly Afrocentric musical culture. The large ensemble model that we imported from European conservatories is incompatible with the riot of polyglot individualism in the kids’ earbuds.

While music therapists have been teaching songwriting for years, it’s rare to find it in school music curricula. Production and beatmaking are even more rare. Not many adults can play oboe in an orchestra, but anyone with a guitar or keyboard or smartphone can write and perform songs. Music performance is a wonderful experience, one I wish were available to everyone, but music creation is on another level of emotional meaning entirely. It’s like the difference between watching basketball on TV and playing it yourself. It’s a way to understand your own innermost experiences and the innermost experiences of others. It changes the way you listen to music, and the way you approach any kind of art for that matter. It’s a tool that anyone should be able to have in their kit. Ableton is doing the music education world an invaluable service; I hope more of us follow their example.