In this paper, I discuss a rap cypher held during a session of NYU’s CORE Music Program on March 3, 2018. A cypher is a group performance where rappers take turns performing improvised verses. Freestyling is to rap what jam sessions are to jazz: an improvisational form that demands both technical proficiency and a relaxed, casual confidence. I chose the cypher as the subject of ethnographic study because it crystallizes so much of what I love about rap generally. Freestyle rap in particular is an underappreciated art. While hip-hop is the most popular genre of music in the United States (Nielsen 2018), and possibly in the world (Hooton 2015), the American music academy does not afford it much respect. I have heard a demoralizingly large number of musicians and educators opine that rap is not music at all. While I do not believe that rap needs academic validation, it is important to me that my fellow educators understand and appreciate the beauty of this music, so if they will not embrace it, they might at least do less to impede it.

Few rap haters will admit to being motivated by racial or class animus. Instead, they point to rap’s supposed lack of melody, or the programmed and sampled beats. Along with electronic dance music, rap in its instrumental aspect is the most repetitive popular form in American history, and schooled musicians are socialized to be contemptuous of repetition (McClary 2004). Improvisation likewise has a low status in academic settings, because spontaneous musical expression supposedly has less significance than composed works (Nettl 1974, 3). However, closer engagement with improvised rap quickly reveals its depth. For example, the predictability of the beats is a necessity to support the complex play of text, pitch, rhythm and timbre in the emcees’ flow. Only by evaluating the music by its own value system can we recognize its beauty.Like any culture, hip-hop can be viewed as “ordered, limiting, and pervasive”, or as “fertile, elaborative, and liberating” (MacDougall 1998, 62). The former view resembles social science or Marxist theory, while the latter is more like literary description of individual experience. I will argue that rap is ordered and limited by strict musical conventions, but that these conventions are optimized to promote elaborative and liberating expression. In the cypher discussed below, the emcees make their personalities and identities felt immediately and strongly. In so doing, they deploy impressive musical and verbal skill with seeming effortlessness. “Regardless of thematics, pleasure and mastery in toasting and rapping are matters of control over the language, the capacity to outdo competition, the craft of the story, mastery of rhythm, and the ability to rivet the crowd’s attention” (Rose 1994, 75). I was the only “audience” member present during the CORE cypher, and I was indeed riveted.

A note about terminology: I use the terms ”rap” and “hip-hop“ interchangeably throughout this paper, in keeping with the usual practice of practitioners and fans. Strictly speaking, rap and hip-hop are not the same thing. Rap is a style of music, while hip-hop is a culture or aesthetic, one component of which is rap music. There can be hip-hop music without rapping, for example, in turntablism or the instrumental albums of DJ Shadow. Conversely, many genres of music predating hip-hop have used rap, including blues, jazz, soul, country, and rock. Nevertheless, when referring to contemporary mainstream music, rap and hip-hop are effectively coextensive.

My musical life has taken place within the Afrodiasporic traditions that gave rise to hip-hop: jazz, rock, funk, and electronic dance music. I have produced a little hip-hop, too, and done a very small amount of rapping. I grew up in New York City, and do not remember a time when I was not at least passively hearing rap around me. However, I am very much an outsider in hip-hop settings, due to a combination of my race, class, age, and sensibilities. A first-time CORE participant introduced herself to me at a session by saying, “You look important.” I gave that impression because I was the oldest person there, and the most formally dressed, not to mention the fact that I was one of only two white people present.

There is a degree to which I am perfectly at home in CORE sessions. This is true in a literal sense—they happen in my workplace, sometimes in my shared office. I am less at home in the metaphorical sense. I am knowledgeable enough about rap to be able to have a conversation about it, and enthusiastic enough as a fan to be able to cross social divides. The participants are friendly toward me, and the regulars greet me warmly with handshakes, fist bumps, and hugs. But I am self-conscious about being a novice and a tourist, about being wack and corny. This is no false modesty on my part: I am a very good musician, but I am not a good rap musician, certainly not by CORE participants’ standards.

I have more privilege than the CORE kids in every respect except in terms of coolness. Without exception, all of the kids are cooler than me, and at least outwardly are correspondingly more confident. For this reason, when I am present for a cypher, I am simultaneously thrilled and terrified by the prospect of getting up and spitting a verse. I did beatbox for a freestyle by one of the CORE mentors during a conference presentation, but I have otherwise kept my own musicality to myself among the participants.

I try to approach the rap musicians of CORE with “positive naïveness” (Madison 2012, 32). Some of this naïvety is genuine, and some is strategic. For an American studying American popular music, “there is no formal beginning or end to our research; our participant observation (i.e., experiencing popular music within the context of American society) covers roughly our entire lives, as do the relationships that we rely on to situate ourselves socially” (Schloss 2013, 8). I am not a naïve participant, but I try to keep my history and opinions to weigh too heavily on observation and interviews.

The CORE Music Program is, per its web site:

an artist mentorship lab, event series, and professional network for young creatives committed to self growth and community engagement hosted at the Music Experience Design Lab (MusEDLab) at New York University. CORE Music NYC is a creative network of support rooted in the shared valuing of freedom, innovation, community, honest expression and the music cultures that inspire us.

The program is run by Jamie Ehrenfeld, a graduate of NYU’s music education program and a teacher at Eagle Academy in Brownsville. The name, chosen by the participants, seems like it might be an acronym, but it does not stand for anything. Each Saturday afternoon, rappers, producers, mentors and friends coalesce in studios and office spaces in NYU Steinhardt’s Education building near Washington Square Park. They write, record, rehearse, listen, study, and socialize. Sometimes there are organized workshops on audio engineering or music business, but most sessions are ad hoc and informal. The program has an ethos of liberatory consciousness, so the participants’ music tends to be more woke than commercial rap, with more focus on social issues and less on partying, guns, or drugs.

CORE participants are young men and women in their teens and early twenties, mostly low-SES people of color. Hip-hop is not the only style of music that they create. Some are singer-songwriters working in a pop, R&B, or rock style. However, hip-hop is the unifying thread. While there is an identifiable group of regulars, actual attendance from week to week is unpredictable. Instead, sessions have a clubhouse feel. Most of the time, no one is really “in charge.” Jamie’s role as director is to provide logistical support, and to be emotionally available and supportive—this sometimes means listening sympathetically, and sometimes means pushing or cajoling the participants.

The CORE working style is low-key, social, casual, and, at times, indistinguishable from simply hanging out. This is well in keeping with the broader norms of hip-hop. Despite the apparent lack of focus, this ad hoc working style is richly generative of original music. After extended socializing, rap artists tend to make their creative choices quickly and decisively.

NYU is a fascinating setting for observations of CORE because it brings racial and class disparities into stark relief. For all its political progressiveness, New York is one of the most racially segregated cities in America (Kucsera & Orfield 2014). NYU students and CORE participants are the same age and live within a few miles of each other, but they occupy very different social worlds. NYU is an expensive private institution, and while not all of its students are wealthy, a substantial percentage certainly are, giving the school a pervasive air of casual privilege. CORE participants, on the other hand, are predominately poor and working-class. The two groups strongly signal their class identity through their respective language, clothing and bodily affect.

CORE meets and works in spaces belonging to NYU Steinhardt’s music technology and music education departments: offices, recording studios, classrooms, conference areas, and lounge areas. During the week, these spaces host academic work, classes, and presentations, where students and faculty work silently or socialize in low-key ways. While NYU’s culture is informal, it is still an academic institution, and the predominant feeling in the common spaces is businesslike. On the rare occasion when music is played in a room, it is almost always during a class or lecture.

The atmosphere during CORE sessions is very different. Music plays through open speakers, sometimes looped endlessly for long periods of time, and usually at high volumes. Socializing is mostly laid back, but can sometimes be loud and rowdy. Both NYU students and CORE participants are casual in their use of profanity, but there is one conspicuous difference: it would be shocking to hear an NYU student to use the word “nigga”, whereas CORE participants say it frequently. One NYU faculty member had brought his young children with him to his office during a session, and he berated me at length about their being exposed to the n-word. I do not like hearing it either, but I understand the difference between its in-group usage and its being spoken in anger. I am teaching my own children to appreciate that difference rather than trying to shield them from the word entirely. In New York, such a thing would be impossible anyway.

CORE periodically records in the James Dolan studio, named for the owner of Madison Square Garden, himself an enthusiastic amateur musician and at one time the parent of two NYU music technology students. The Dolan Studio is one of the best in New York, with top-of-the-line equipment and immaculate acoustics. The monitor speakers alone cost twenty thousand dollars, and the mixing desk costs on the order of a hundred thousand. The CORE participants like working there, because it makes them feel like “real” artists. For all its luxuriousness, though, the Dolan studio is not an optimal space for hip-hop creation. It was designed to capture live performances using Pro Tools, not for creative electronic production with Logic or FL Studio or Ableton Live. For rap purposes, all that is needed is a small soundproof room with a computer, an audio interface, and a microphone. The program has more regular access to such a space, as well as the computers in labs and offices.

CORE sessions ostensibly start at 2:00 pm, but some participants show up hours earlier, while others arrive hours later. On the day of the cypher I will be discussing, people are still arriving at 4:30, eating, chatting, and listening to music. The session does not really get going until 5:00. The group assembles in a nondescript conference room. There are about twenty people present, including a small camera crew, filming for what purpose I don’t know. No one seems particularly concerned by or even interested in their presence. Certainly no one is signing any release forms. There is a small PA system set up, with music playing a laptop belonging to Brandon Bennett, one of the regulars.

When I enter the room, the song playing is “Everything (Remix)” by G Herbo featuring Chance the Rapper and Lil Uzi Vert (2018). The CORE participants love and admire Chance, but his verse on this song is less woke than usual:

Knew the game, still you gave that bitch a wedding ring

I took her number, gave her NuvaRing and never rang

Never give ’em everything

When I hear this line, I simultaneously feel two strong and conflicting emotions: disapproval of the misogyny, and amusement at Chance’s wordplay. Rap shares many traits with standup comedy, including the use of deliberate offensiveness as a way to provoke laughs. I try to balance my moral indignation with an awareness that white observers of such jokes tend to see the aggression but miss the playfulness (Gates 1988, 68).

Profane and/or violent lyrics go back in black culture as far as the blues and the baaadman tales of the nineteenth century, if not much further.

Irreverence has been a central component of black expressive vernacular culture, which is why violence and sex have been as important as toasting and signifying as playfulness with language. Many of these narratives are about power. Both the baaadman and the trickster embody a challenge to embody a challenge to virtually all authority (which makes sense to people for whom justice is a rare thing), creates an imaginary upside-down world where the oppressed are the powerful, and it reveals to listeners the pleasures and price of reckless abandon (Kelley 1996, 187).

While we should not take irreverent language too literally, it is nevertheless hard on girls and women. Female rap fans and emcees are reclaiming the word “bitch” in empowering and creative ways, but nevertheless, rap’s gender politics are heavily patriarchal.

Black women and girls, who are increasingly “celebrated” in songs and videos as “bad bitches,” are simultaneously rendered irrelevant when it comes to hip hop authorship, video direction, and music production. The same can be said of hip hop’s lyrics and visual themes objectifying black female voices and bodies (Gaunt 2015, 213).

Toni Blackman, a CORE mentor, is deeply politically conscious, but also susceptible to the profane charms of current rap.

I was on a date with my friend [and] that song “All that good kush and alcohol” comes on. It’s one of those songs like [she pauses], I think the music is meditative and trance-like, and I think the melodies [Weezy and Future] use to rap in, they’re just… they’re addictive, you know? Like, literally for two weeks I was waking up singing this song [she chuckles] ya know??! Imagine an 11- or 12-year-old who is not that conscious of how to program their mind and their thoughts, [and] doesn’t have their critical thinking skills yet. And here I am with all of this seasoning and experience, and I can’t control it [she chuckles again] (quoted in Gaunt 2015, 220).

Rap’s gender dynamics will appear in several places in the cypher discussion below.

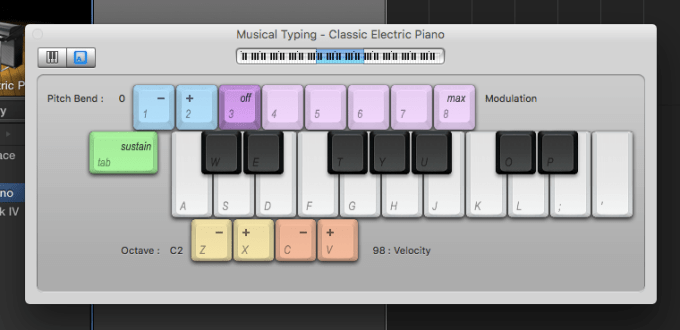

To begin the cypher, Brandon opens FL Studio and plays one of his original beats. It is a trap beat comprised of a sampled or simulated Roland TR-808 drum machine, a sampled tabla, and a sampled or synthesized bamboo flute. Brandon later tells me that he created the beat in fifteen minutes, beating his previous speed record of thirty minutes. The two-measure beat will repeat for the better part of an hour, with the only variation being the muting and then unmuting of the flute part.

As is common to trap music, Brandon’s track is slow, with drums accenting fine subdivisions of the beat. Aside from the kick drum on each downbeat, the snare drum hits on the backbeats (beats two and four) are the most stable element in the pattern. The accented backbeat is a characteristic shared by every African-American vernacular music, including jazz, country, rock, funk, techno, and rap. Technically, the backbeat is a syncopation, the rhythmic equivalent of tension or dissonance. However, Biamonte (2014, [6.2]) argues that the backbeat has become a rhythmic consonance through sheer force of repetition. It certainly feels stable compared to the skittering hi-hats in Brandon’s beat.

The tempo of Brandon’s FL Studio session is 140 beats per minute rather than 70. The drum machine interface in FL Studio uses a sixteenth note grid, so to use thirty-second notes, it is more expedient to work in cut time.

Trap beats show the “exaggerated virtuosity of the machine” (Danielsen 2010, 2)–the uncannily fast and perfect drum hits advertise their artificiality. Rap has always been an electronic music, but in earlier eras, there was clear reference to human drumming, either because the beats were sampled from live funk and soul performances, or because drum machines were programmed to have a similar sound to those samples. Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of the Roots is the best exemplar of an acoustic drummer who plays in a classic hip-hop style. On the other hand, even if Questlove could play trap rhythms, he certainly could not replicate the unearthly timbre of a programmed 808 on a drum kit.

Hearing identical repetitions of a sampled or programmed beat is uncanny to begin with, but hearing those identical repetitions over very long spans is a phenomenological experience with little precedent in music. During the cypher, we heard Brandon’s beat repeat hundreds of times. Tape loops might subtly wobble in pitch, but computer repetitions are perfect. While the experience of endless digital looping may be a futuristic one, it is continuous with the traditions of Afrodiasporic music. The beat is a stable and reliable presence, and “it is there for you to pick it up when you come back to get it… Without an organizing principle of repetition, true improvisation would be impossible, since an improviser relies upon the ongoing recurrence of the beat” (Snead 1984, 67-68). Robert Henke, a musician and co-creator of Ableton Live, points out that the computer is highly amenable to creating stable and reliable beats.

[I]n electronic music, there’s a lot of ways to create something that runs—that is static, but nevertheless, it’s creating something. Take a drum computer: you turn it on and it plays a pattern. And you cannot turn on a drummer. A drummer always has to do something in order to work. And the drum computer, you turn it on and the pattern is there (quoted in Butler 2014, 105).

In the analysis that follows, I juxtapose recordings of the cypher with my own sound writing, both prose and notation. There is some overlap between recording and writing—the word phonography literally means “sound writing.” I could simply let the recording speak for itself, but that would not adequately convey the full experience of being in the room. Weidenbaum (2017) observes that recording never sounds like what he heard—listening is a process of focusing and filtering, of selective attention and interpretation, an experience that is quite different from the microphone’s direct transcription. While Kapchan (2017) wants her sound writing to have the full sensual richness of sound itself, Weidenbaum prefers writing exactly because it does not have the rich texture of recorded sound. Recording playback is a new sensory experience unto itself, one that might be far removed from the one the recordist meant to capture or convey. It is more useful for me to think of the recording, writing and transcription as methods of “flat ethnography, where you slice into a world from different perspectives, scales, registers, and angles—all distinctively useful, valid, and worthy of consideration” (Jackson 2013, 16-17). Between these slices, I hope that the reader can triangulate a fuller sense of the experience of the cypher.

A note about my trascriptions: the pitches are very loose approximations, meant to show general melodic contour only. The actual pitches in rap vocals do not usually align with the piano-key notes, and are not stable even within individual syllables. Rhythmically, my notation is closer to being a literal representation. However, there are many nuances of rushed or dragged rhythm that I do not show, because that would make the notation unreadable. So the rhythms should be understood as somewhat approximate as well. One might well ask why it is worth transcribing rap at all. Anyone who wishes to study the cypher can simply listen to tbe recording. My transcriptions are meant in part as an ironic commentary, a way to represent rap in the language of “real” musicology as a way of commenting on that language. I want this paper to be legible to musicologists, but I do not wish to “go native” as a musicologist either.

[P]revious transcribers of hip-hop music, who were acting (implicitly or explicitly) as defenders of hip-hop’s musical value, have naturally tended to foreground the concerns of the audiences before whom they were arguing, which consisted primarily of academics trained in western musicology. This approach requires that one operate, to some degree, within the conceptual framework of European art music: pitches and rhythms should be transcribed, individual instruments are to be separated in score form, and linear development is implicit, even when explicitly rejected (Schloss 2013, 13-14).

As the cypher begins, participants go around the circle doing verses. There is some freestyling, but mostly people read verses out of their notebooks. The energy in the room is low until Jamie prompts everyone to get up out of their chairs. There are some instrumentalists present: a young woman named LeiOra jams on the viola, and a young man whose name I do not know plays jazzy chords on an acoustic guitar.

Eventually the camera crew and their friends leave the room. About twelve of us remain in the circle. Perhaps not coincidentally, this is when genuine freestyling begins in earnest. (This is also the point where my recording begins.) The tone is playful and jokey for the first few minutes. Then Brandon unmutes the meditative flute track on his beat, which changes the mood—a participant remarks, “Oh, time to get serious now.” The freestyle verses after this point get longer and more adventurous. They are still jokey, but a wider variety of emotions appear as well. For example, Brandon raps about his fear of doctors, heights, and needles. While everyone in the circle participates to some degree, there are three dominant performers: Brandon, Roman, and LeiOra. I profile each of them below.

Brandon is a nineteen year old Bronx native. He is tall and thin, with tidy waist-length dreadlocks and a beard that gives him a shamanistic look. He raps and performs as a DJ, but he considers himself to be primarily a producer, and is an extremely prolific one. His style spans trap, hip-hop, RnB, and house, and he favors a lo-fi sound, with thick reverb, vinyl noise, and a softened high end. Brandon produces using FL Studio, Pro Tools, Logic Pro, and an SP-404A sampler. He has been making beats since age 14, and has taught production workshops at a professional level. His SoundCloud and BandCamp accounts are mostly beats, but when he does appear as an emcee, he rhymes with seriousness and vulnerability. His main SoundCloud account has over a thousand followers, and he pays close attention to their feedback. However, since his followers reacted negatively to some his more experimental music, he started a second account to host that material.

In hip-hop and other electronic popular forms, the term “producer” has come to encompass songwriting, beatmaking, MIDI sequencing, instrumental and vocal performance, and audio manipulation (Moir and Medbøe, 2015). Danielsen (2010) asks what word we should use to describe a user of a program like FL Studio: producer, engineer, composer or performer? The answer is all of the above, or none of the above. There are no clear boundaries between such roles in the digital studio context.

Roman is a high school senior. He is baby-faced, and looks younger than he is. I have never seen him without his white Beats headphones on his ears. His given name is Maximus, and he draws his emcee name and iconography from ancient Rome. For example, his crew is called Vongola, the Italian word for clam. (Roman explains that vongolas clean dirty water.) Roman continues to be close to his crew, even though they no longer all attend the same school.

Identity in hip hop is deeply rooted in the specific, the local experience, and one’s attachment to and status in a local group or alternative family. These crews are new kinds of families forged with intercultural bonds that, like the social formation of gangs, provide insulation and support in a complex and unyielding environment and may serve as the basis for new social movements (Rose 1994, 55).

Roman is intensely committed to emceeing. He uses the same learning process as a jazz musician: continually memorizing other people’s verses by ear from recordings, a line at a time. He has even learned a few verses in foreign languages phonetically.

A few weeks after the cypher, Roman gives me an in-depth listening tour to some emcees he admires. He is particularly interested in Midwest Chop, a technically demanding style that crams as many syllables into the bar as possible without sacrificing clear articulation or wordplay. Roman plays me verses by Logic, Joyner Lucas, Tech N9ne, Eminem, and Busta Rhymes as examples. You can get a good sense of the style from Busta Rhymes’ extraordinary verse on “Worldwide Choppers” by Tech N9ne (2011). Roman’s favored rappers span generations—Logic is currently popular, but Busta Rhymes is from my era. The trait they share is dazzling virtuosity. If you think of Rakim Allah as corresponding to Charlie Parker, then Tech N9ne is more like John Coltrane in his “sheets of sound” phase.

Some scholars (e.g. Wilson 2001) compare rap to scat singing in jazz. Listening to Midwest Chop reminds me more of vocalese, where jazz vocalists write lyrics for recorded improvised solos. The best vocalese practitioners, like Lambert, Hendricks and Ross, sing intricate bebop lines packed with syllables. Roman is impressed by sheer syllable count, and is pushing himself on his speed, but he has not lost sight of wanting to be funny, and, sometimes, heartfelt. His favorite artist is Chance the Rapper, who has technical ability but is best known for being vulnerable and emotionally direct. Roman maintains a fan-curated SoundCloud playlist of Chance’s live performances. He particularly admires Merry Christmas Lil’ Mama (2016), a Christmas-themed mixtape Chance created with the R&B singer Jeremih. On these songs, Chance reminisces about his childhood and mourns dead family members, setting an emotional tone that is far removed from his verse about the NuvaRing.

I do not know LeiOra well; she is not a regular, and the day of the cypher is her first time at a session. She is 23 years old and Latina. She is in the building for a recording session in the Dolan Studio with Toni Williams, a singer-songwriter who graduated recently from NYU and is part of the CORE circle. After recording, LeiOra is invited to the cypher, and she joins spontaneously.

LeiOra has a gift for creating memorable hooks off the top of her head, several of which she repeats in chantlike fashion, both in her own verses and as background for others. She shows remarkable self-assurance in her willingness to freestyle among a group of complete strangers, nearly all of whom are male. Nevertheless, she is less assertive in the cypher than Brandon or Roman, as I will discuss below.

When emcees improvise, “they use words and expressions in the same way as jazz/rock musicians use scales and riffs in their improvisations” (Söderman & Folkestad 2004). The cypher is emblematic of what Turino (2008) describes as participatory performance. In such performances, the audience/artist distinction is blurry or nonexistent. The participants may have widely varying skill levels, so the music has a low floor for core participation (e.g. shaking a shaker steadily) and a high ceiling for elaboration (e.g. playing virtuoso lead percussion). The form of participatory music is open, cyclical and very repetitive. There might be extensive improvisation, but it takes place within predictable structures. Beginnings and endings of songs are “feathered”—unscripted, loose, and sometimes disorderly. The music is game-like, though usually without “winners” or “losers.” People in participatory cultures prefer skillful musicians over inept ones, but the social aspect of the music is the most important one, and it is good manners to keep critical judgment of the performance to oneself. CORE participants enact this participatory value when they are sharply critical of commercial recordings, but rarely criticize each other.

Rap cyphers have less structure than other participatory improvisational forms. Cyphers resemble improv comedy more than jazz or blues jams. In a jazz jam session, solos come in predefined units, e.g. thirty-two bar choruses. In a cypher, by contrast, each person begins and ends whenever they want. The rhymes are not completely unstructured, however; they follow a formal “model” (Nettl 1974, 12) that resembles written rap. For example, emcees almost always rap phrases whose lengths in bars are powers of two. Rhymes usually fall at the end of phrases, though more advanced emcees also use internal rhymes. Rose (1994) points out that for all of its technological innovations, rap music “has also remained critically linked to black poetic traditions and the oral forms that underwrite them. These oral traditions and practices clearly inform the prolific use of collage, intertextuality, boasting, toasting, and signifying in rap’s lyrical style and organization” (84). The subject matter in the cypher is wide open, but the tone is not. Rappers have a very particular affect, which I describe as “fresh.” The meaning of the word in a hip-hop context can refer to any of its conventional senses: new, refreshing, appetizing, attractive, or sassy (Hein 2015). Rappers must be irreverent, culturally attuned, and above all, cool.

In the sections below, I discuss three excerpts of the cypher in depth. The entire recording is available for download here.

Excerpt one: 0:14 – 0:40

The cypher participants form an approximate circle, with the three main emcees at the points of an equilateral triangle. Brandon stands, with his gaze directed at a point on the floor in front of him. He is inward-directed, though still responsive to the room. Roman stands too, with his gaze directed outward. A few members of his crew stand and sit nearby. LeiOra sits on a table, with her gaze also outward-directed. Amid the hubbub of the film crew leaving, Brandon begins warming up, getting into his flow. He lists foods and other things he likes, using a formulaic construction: an eighth rest, “I like” on sixteenth notes, then the object of the phrase:

I like shakes, I like tacos

I like tacos, I like burritos

I like Doritos and Cheetos

I don’t like Fritos cause they kinda too salty

So get up off me

I like, I like schools, I like Snickers

I like Twix and action figures

In many rap songs, “the meaning of the text is often secondary to its interaction with the music” (Adams 2008, 43), and that is certainly true here. Brandon is choosing words for their sound more than trying to convey any particular meaning. Some of his rhymes are direct (burritos/Doritos/Cheetos/Fritos), while others are slant rhymes (salty/off me, Snickers/figures). Throughout this excerpt, other people are shouting out foods they like and joking around, but Brandon gradually draws the focus of the room. He and the other emcees will keep returning to the theme of food throughout the cypher.

Adams (2009) recommends that we analyze rap by examining the metrical and articulative aspects of emcee flow. Metrical aspects include the placement of rhymes and syllabic stresses, the relationship between bar lines or hypermeasures and lyrical phrase boundaries, and the syllable count per beat. You can see the metrical aspects of Brandon’s flow in the way that he varies his simple formula, displacing the phrase forward and backward in the meter, placing it on stronger and weaker beats. Articulative aspects of rap include the use of staccato or legato, the articulation of consonants, and the placement of syllables ahead of or behind the beat. You can hear Brandon’s articulative technique in the way that he slightly drags the timing of “kinda too salty” and “get up off me,” and the way he indicates ironic exasperation by raising his pitch on “off me”.

Excerpt two: 3:11 to 3:40

Like most contemporary emcees, Roman and Brandon use what Krims (2000) calls a “speech-effusive style,” featuring the casual enunciation and loose rhythms of everyday spoken language. By contrast, LeiOra’s style is what Krims describes as “sung,” a schoolyard chant feel with on-beat accents and strict couplet groupings. In this excerpt, Roman also moves into a “percussion-effusive” style, a more rhythmically complex flow that is more free with metrical boundaries and rhyme schemes, but which still has crisp articulation and clearly discernable regular rhythm patterns. You can hear the influence of Midwest Chop in his doubletime phrasing:

Chicken and rice, sofrito with spice

Flip it on my plate, makin’ it nice

LeiOra replies with a parodic singsong, in an exaggerated Nuyorican accent:

Don’t forget Adobo, don’t forget Adobo, cause you already loco

Roman takes LeiOra’s cue, adopting the same accent and rapping in Spanglish:

Makin’ fine desayuno with that queso frito

LeiOra begins chanting “Que wepa! Wepa!” repeatedly. She brings a raucous harshness into her voice, an example of the way that black musics cultivate a wide range of vocal sounds connected to tonal speech patterns, ranging across different registers (Rose 1994, 86). Brandon jumps in over her chant–one of several instances where male emcees interrupt her–and extends the Nuyorican theme:

So when I get chicken, put Adobo and Sazón,

If you ain’t got Sazón, don’t allow me in your home!

The rest of the room yells in approval.

Excerpt three: 3:53 – 4:17

LeiOra’s best hook is this one: “Dab when you cough, dab when you sneeze,” repeated in her singsong cadence. It refers to an internet meme (SchoolMemes 2017). Roman and others do little interjections in between her lines, e.g. “Achoo!” Then, after twelve times through LeiOra’s chant, Roman jumps forward and interrupts with a punchline: “I’m so nice with it, I dab with my knees!” The entire room erupts with laughter. This is an example of signifying, an unexpected satirical twist on a familiar element.

It is as if a received structure of crucial elements provides a basis for poeisis, and the narrator’s technique, his or her craft, is to be gauged by the creative (re)placement of these expected or anticipated formulaic phrases and formulaic events, rendered anew in unexpected ways. Precisely because the concepts represented in the poem are shared, repeated, and familiar to the poet’s audience, meaning is devalued while the signifier is valorized (Gates 1988, 61).

We can look at freestyle rap through “the lenses of containment and possibility” (Hayes 2010, 31). The flows are contained by the unvarying beat and the demands of rhyme and musical structure. Their possibilities include community, humor, and cultural confidence. When a cultural conservative like Scruton (2014) dismisses “the tuneless aggression of rap” (n.p.), he does not just insult a rich musical tradition. He insults the young people around the world who use that tradition for validation, support, and representation. Furthermore, to dismiss rap is to dismiss a valuable set of tools for understanding other forms of music as well. It can be enlightening to listen to Western art music through a hip-hop frame, to hear how much it loses by eschewing repetition, to taste its lack of freshness, to examine its timbres with a producer’s ear, and to question its assumptions. “[O]nly when others are freed to pursue their own trajectories can Western music properly acknowledge the multiplicity of differences lying beneath its authoritarian binaries and become productively other to itself” (Middleton 2000).

Jamie Ehrenfeld once commented to me: “I got a music degree without ever writing a song” (personal communication, April 29 2017). She similarly had no opportunity in her schooling to engage with the creative processes behind popular music. Her experience is a typical one—composition and songwriting are rarities in American music education settings (Beckstead 2001). In an era when any laptop or smartphone can be used as a full-flight production studio, this is a grievous missed opportunity. It has never been easier in recent memory for young people to produce the music that is culturally relevant to them. The only remaining obstacle is institutional lack of respect for the music.

References

Adams, K. (2015). The musical analysis of hip-hop. In J. Williams (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Hip-Hop (pp. 118–134). Cambridge University Press.

Adams, K. (2008). Aspects of the Music/Text Relationship in Rap. Music Theory Online, 14(2). Retrieved from http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.2/mto.08.14.2.adams.html

Adams, K. (2009). On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music. Music Theory Online, 15(5), 1–12. Retrieved from http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.09.15.5/mto.09.15.5.adams.html

Beckstead, D. (2001). Will technology transform music education? Music Educators Journal, 87(6), 44–49.

Biamonte, N. (2014). Formal Functions of Metric Dissonance in Rock Music. Music Theory Online, 20(2). Retrieved from http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.biamonte.php

Butler, M. (2014). Playing with Something That Runs: Technology, Improvisation, and Composition in DJ and Laptop Performance. Oxford University Press.

Danielsen, A. (2010). Musical Rhythm in the Age of Digital Reproduction. Ashgate. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Gates, H. L. (1989). Signifying Monkey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gaunt, K. (2015). YouTube, Bad Bitches, and an M.I.C. (Mom-in-Chief) : On the Digital Seduction of Black Girls in Participatory Hip-Hop Spaces. In T. Gosa & E. Nielsen (Eds.), The Hip Hop & Obama Reader (pp. 207–226). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hayes, E. (2010). Songs in Black and Lavender : Race, Sexual Politics, and Women’s Music. University of Illinois Press.

Hein, E. (2015). Mad Fresh. Retrieved March 24, 2015, from http://www.newmusicbox.org/articles/mad-fresh/

Hooton, C. (2015). Hip-hop is the most listened to genre in the world, according to Spotify analysis of 20 billion tracks. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/hip-hop-is-the-most-listened-to-genre-in-the-world-according-to-spotify-analysis-of-20-billion-10388091.html

Jackson, J. (2013). Thin description : ethnography and the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem. Harvard University Press.

Kapchan, D. (2017). Theorizing Sound Writing. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Krims, A. (2000). Rap music and the poetics of identity. Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.2307/3595215

Kucsera, J., & Orfield, G. (2014). New York State’s Extreme School Segregation: Inequality, Inaction and a Damaged Future. Retrieved from http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/ny-norflet-report-placeholder

MacDougall, D. (1998). Transcultural Cinema. Princeton University Press.

Madison, D. S. (2012). Methods: “ Do I Really Need a Method ?” A Method … or Deep Hanging-Out. Critical Ethnography: Method, Ethics, and Performance. Sage Publications. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452233826.n2

McClary, S. (2004). Rap, minimalism, and structures of time in late twentieth-century culture. In D. Warner (Ed.), Audio Culture. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Middleton, R. (2000). Musical belongings: Western music and its low-other. In G. Born & D. Hesmondhalgh (Eds.), Western Music and Its Others : Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music (pp. 59–85). University of California Press.

Moir, Z., & Medbøe, H. (2015). Reframing popular music composition as performance-centred practice. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 8(2), 147–161. http://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.8.2.147

Nettl, B. (1974). Thoughts on improvisation: A comparative approach. Musical Quarterly, 60(1), 1–19.

Nielsen. (2018). 2017 U.S. Music Year-End Report. Retrieved April 19, 2018, from http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2018/2017-music-us-year-end-report.html

Rose, T. (1994). Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (1st ed.). Hanover, N.H.: Wesleyan.

Schloss, J. G. (2013). Making Beats: The Art of Sample-Based Hip-hop. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

SchoolMemes. (2017). Bad Acronyms – Don’t spread germs! DAB when you sneeze! Retrieved May 3, 2018, from http://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1280450-bad-acronyms

Small, C. (2011). Music of the Common Tongue : Survival and Celebration in African-American Music. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-322-0

Snead, J. A. (1984). Repetition as a figure of black culture. In H. L. Gates (Ed.), Black Literature and Literary Theory (3rd ed., pp. 59–79). Taylor & Francis Group.

Söderman, J., & Folkestad, G. (2004). How Hip-Hop Musicians Learn: Strategies in Informal Creative Music Making. Music Education Research, 6(3), 313–326. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ681164

Turino, T. (2008). Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/M/bo5867463.html

Weidenbaum, M. (2017). Audio or It Didn’t Happen. Retrieved June 14, 2017, from http://www.newmusicbox.org/articles/audio-or-it-didnt-happen/

Wilson, O. (2001). “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing” : the relationship between African and African American music. In S. Walker (Ed.), African roots/American cultures : Africa in the creation of the Americas (pp. 153–168). New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Discography

G Herbo featuring Chance the Rapper and Lil Uzi Vert (2018). Everything (Remix) [digital download]. New York: Machine/150 Dream Team/Cinematic/RED. (February 15, 2018)

Jeremih and Chance the Rapper (2016). Merry Christmas Lil’ Mama [digital download]. Self-released. (December 22, 2016)

Tech N9ne featuring Busta Rhymes, Ceza, D-Loc, JL B.Hood, Twista, Twisted Insane, U$O and Yelawolf (2011). Worldwide Choppers. On All 6’s and 7’s [digital download]. Lee’s Summit, MO: Strange Music. (May 1, 2011)