Writing assignment for Design For The Real World with Claire Kearney-Volpe and Diana Castro – research about a new rhythm interface for blind and low-vision novice musicians

Definition

I propose a new web-based accessible rhythm instrument called QWERTYBeats.Traditional instruments are highly accessible to blind and low-vision musicians. Electronic music production tools are not. I look at the history of accessible instruments and software interfaces, give an overview of current electronic music hardware and software, and discuss the design considerations underlying my project.

Historical overview

Acoustic instruments give rich auditory and haptic feedback, and pose little obstacle to blind musicians. We need look no further for proof than the long history of iconic blind musicians like Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder. Even sighted instrumentalists rarely look at their instruments once they have attained a sufficient level of proficiency. Music notation is not accessible, but Braille notation has existed since the language’s inception. Also, a great many musicians both blind and sighted play entirely by ear anyway.

Most of the academic literature around accessibility issues in music education focuses on wider adoption of and support for Braille notation. See, for example, Rush, T. W. (2015). Incorporating Assistive Technology for Students with Visual Impairments into the Music Classroom. Music Educators Journal, 102(2), 78–83. For electronic music, notation is rarely if ever a factor.

Electronic instruments pose some new accessibility challenges. They may use graphical interfaces with nested menus, complex banks of knobs and patch cables, and other visual control surfaces. Feedback may be given entirely with LED lights and small text labels. Nevertheless, blind users can master these devices with sufficient practice, memorization and assistance. For example, Stevie Wonder has incorporated synthesizers and drum machines in most of his best-known recordings.

Most electronic music creation is currently done not with instruments, but rather using specialized software applications called digital audio workstations (DAWs). Keyboards and other controllers are mostly used to access features of the software, rather than as standalone instruments. The most commonly-used DAWs include Avid Pro Tools, Apple Logic, Ableton Live, and Steinberg Cubase. Mobile DAWs are more limited than their desktop counterparts, but are nevertheless becoming robust music creation tools in their own right. Examples include Apple GarageBand and Steinberg Cubasis. Notated music is commonly composed using score editing software like Sibelius and Finale, whose functionality increasingly overlaps with DAWs, especially in regard to MIDI sequencing.

DAWs and notation editors pose steep accessibility challenges due to their graphical and spatial interfaces, not to mention their sheer complexity. In class, we were given a presentation by Leona Godin, a blind musician who records and edits audio using Pro Tools by means of VoiceOver. While it must have taken a heroic effort on her part to learn the program, Leona demonstrates that it is possible. However, some DAWs pose insurmountable problems even to very determined blind users because they do not use standard operating system elements, making them inaccessible via screen readers.

Technological interventions

There are no mass-market electronic interfaces specifically geared toward blind or low-vision users. In this section, I discuss one product frequently hailed for its “accessibility” in the colloquial rather than blindess-specific sense, along with some more experimental and academic designs.

Ableton Push

Ableton Live has become the DAW of choice for electronic music producers. Low-vision users can zoom in to the interface and modify the color scheme. However, Live is inaccessible via screen readers.

In recent years, Ableton has introduced a hardware controller, the Push, which is designed to make the software experience more tactile and instrument-like. The Push combines an eight by eight grid of LED-lit touch pads with banks of knobs, buttons and touch strips. It makes it possible to create, perform and record a piece of music from scratch without looking at the computer screen. In addition to drum programming and sampler performance, the Push also has an innovative melodic mode which maps scales onto the grid in such a way that users can not play a wrong note. Other comparable products exist; see, for example, the Native Instruments Maschine.

There are many pad-based drum machines and samplers. Live’s main differentiator is its Session view, where the pads launch clips: segments of audio or MIDI that can vary in length from a single drum hit to the length of an entire song. Clip launching is tempo-synced, so when you trigger a clip, playback is delayed until the start of the next measure (or whatever the quantization interval is.) Clip launching is a forgiving and beginner-friendly performance method, because it removes the possibility of playing something out of rhythm. Like other DAWs, Live also gives rhythmic scaffolding in its software instruments by means of arpeggiators, delay and other tempo-synced features.

The Push is a remarkable interface, but it has some shortcomings for blind users. First of all, it is expensive, $800 for the entry-level version and $1400 for the full-featured software suite. Much of its feedback is visual, in the form of LED screens and color-coded lighting on the pads. It switches between multiple modes which can be challenging to distinguish even for sighted users. And, like the software it accompanies, the Push is highly complex, with a steep learning curve unsuited to novice users, blind or sighted.

The aQWERTYon

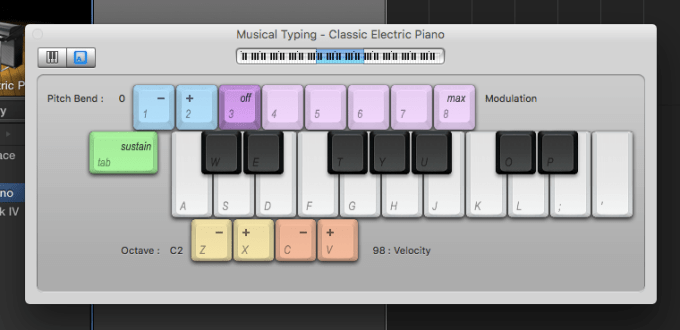

Most DAWs enable users to perform MIDI instruments on the QWERTY keyboard. The most familiar example is the Musical Typing feature in Apple GarageBand.

Musical Typing makes it possible to play software instruments without an external MIDI controller, which is convenient and useful. However, its layout counterintuively follows the piano keyboard, which is an awkward fit for the computer keyboard. There is no easy way to distinguish the black and white keys, and even expert users find themselves inadvertantly hitting the keyboard shortcut for recording while hunting for F-sharp.

The aQWERTYon is a web interface developed by the NYU Music Experience Design Lab specifically intended to address the shortcomings of Musical Typing.

Rather than emulating the piano keyboard, the aQWERTYon draws its inspiration from the chord buttons of an accordion. It fills the entire keyboard with harmonically related notes in a way that supports discovery by naive users. Specifically, it maps scales across the rows of keys, staggered by intervals such that each column forms a chord within the scale. Root notes and scales can be set from pulldown menus within the interface, or preset using URL parameters. It can be played as a standalone instrument, or as a MIDI controller in conjunction with a DAW. Here is a playlist of music I created using the aQWERTYon and GarageBand or Ableton Live:

The aQWERTYon is a completely tactile experience. Sighted users can carefully match keys to note names using the screen, but more typically approach the instrument by feel, seeking out patterns on the keyboard by ear. A blind user would need assistance loading the aQWERTYon initially and setting the scale and root note parameters, but otherwise, it is perfectly accessible. The present project was motivated in large part by a desire to make exploration of rhythm as playful and intuitive as the aQWERTYon makes exploring chords and scales.

Soundplant

The QWERTY keyboard can be turned into a simple drum machine quite easily using a free program called Soundplant. The user simply drags audio files onto a graphical key to have it triggered by that physical key. I was able to create a TR-808 kit in a matter of minutes:

After it is set up and configured, Soundplant can be as effortlessly accessible as the aQWERTYon. However, it does not give the user any rhythmic assistance. Drumming in perfect time is an advanced musical skill, and playing drum machine samples out of time is not much more satisfying than banging on a metal bowl with a spoon out of time. An ideal drum interface would offer beginners some of the rhythmic scaffolding and support that Ableton provides via Session view, arpeggiators, and the like.

Drum machines and their software counterparts offer an alternative form of rhythmic scaffolding. The user sequences patterns in a time-unit box system or piano roll, and the computer performs those patterns flawlessly. The MusEDLab‘s Groove Pizza app is a web-based drum sequencer that wraps the time-unit box system into a circle.

The Groove Pizza was designed to make drum programming more intuitive by visualizing the symmetries and patterns inherent in musical-sounding rhythms. However, it is totally unsuitable for blind or low-vision users. Interaction is only possible through the mouse pointer or touch, and there are no standard user interface elements that can be parsed by screen readers.

Before ever considering designing for the blind, the MusEDLab had already considered the Groove Pizza’s limitations for younger children and users with special needs: there is no “live performance” mode, and there is always some delay in feedback between making a change in the drum pattern and hearing the result. We have been considering ways to make a rhythm interface that is more immediate, performance-oriented and tactile. One possible direction would be to create a hardware version of the Groove Pizza; indeed, one of the earliest prototypes was a hardware version built by Adam November out of a pizza box. However, hardware design is vastly more complex and difficult than software, so for the time being, software promises more immediate results.

Haenselmann-Lemelson-Effelsberg MIDI sequencer

This experimental interface is described in Haenselmann, T., Lemelson, H., & Effelsberg, W. (2011). A zero-vision music recording paradigm for visually impaired people. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 5, 1–19.

The authors create a new mode for a standard MIDI keyboard that maps piano keys to DAW functions like playback, quantization, track selection, and so on. They also add “earcons” (auditory icons) to give sonic feedback when particular functions have been activated that normally only give graphical feedback. For example, one earcon sounds when recording is enabled; another sounds for regular playback. This interface sounds promising, but there are significant obstacles to its adoption. While the authors have released the source code as a free download, that requires a would-be user to be able to compile and run it. This is presuming that they could access the code in the first place; the download link given in the paper is inactive. It is an all-too-common fate of academic projects to never get widespread usage. By posting our projects on the web, the MusEDLab hopes to avoid this outcome.

Statement

Music education philosophy

My project is animated by a constructivist philosophy of music education, which operates by the following axiomatic assumptions:

- Learning by doing is better than learning by being told.

- Learning is not something done to you, but rather something done by you.

- You do not get ideas; you make ideas. You are not a container that gets filled with knowledge and new ideas by the world around you; rather, you actively construct knowledge and ideas out of the materials at hand, building on top of your existing mental structures and models.

- The most effective learning experiences grow out of the active construction of all types of things, particularly things that are personally or socially meaningful, that you develop through interactions with others, and that support thinking about your own thinking.

If an activity’s challenge level is beyond than your ability, you experience anxiety. If your ability at the activity far exceeds the challenge, the result is boredom. Flow happens when challenge and ability are well-balanced, as seen in this diagram adapted from Csikszentmihalyi.

Music students face significant obstacles to flow at the left side of the Ability axis. Most instruments require extensive practice before it is possible to make anything that resembles “real” music. Electronic music presents an opportunity here, because even a complete novice can produce music with a high degree of polish quickly. It is empowering to use technologies that make it impossible to do anything wrong; it frees you to begin exploring what you find to sound right. Beginners can be scaffolded in their pitch explorations with MIDI scale filters, Auto-Tune, and the configurable software keyboards in apps like Thumbjam and Animoog. Rhythmic scaffolding is more rare, but it can be had via Ableton’s quantized clip launcher, by MIDI arpeggiators, and using the Note Repeat feature on many drum machines.

QWERTYBeats proposal

My project takes drum machine Note Repeat as its jumping off point. When Note Repeat is activated, holding down a drum pad triggers the corresponding sound at a particular rhythmic interval: quarter notes, eighth notes, and so on. On the Ableton Push, Note Repeat automatically syncs to the global tempo, making it effortless to produce musically satisfying rhythms. However, this mode has a major shortcoming: it applies globally to all of the drum pads. To my knowledge, no drum machine makes it possible to simultaneously have, say, the snare drum playing every dotted eighth note while the hi-hat plays every sixteenth note.

I propose a web application called QWERTYBeats that maps drums to the computer keyboard as follows:

- Each row of the keyboard triggers a different drum/beatbox sound (e.g. kick, snare, closed hi-hat, open hi-hat).

- Each column retriggers the sample at a different rhythmic interval (e.g. quarter note, dotted eighth note).

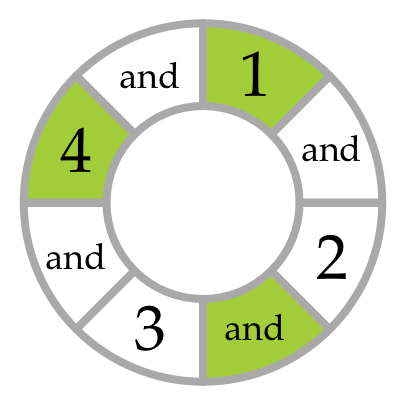

- Circles dynamically divide into “pie slices” to show rhythmic values.

The rhythm values are shown below by column, with descriptions followed by the time interval as shown as a fraction of the tempo in beats per minute.

- quarter note (1)

- dotted eighth note (3/4)

- quarter note triplet (2/3)

- eighth note (1/2)

- dotted sixteenth note (3/8)

- eighth note triplet (1/3)

- sixteenth note (1/4)

- dotted thirty-second note (3/16)

- sixteenth note triplet (1/6)

- thirty-second note (1/8)

By simply holding down different combinations of keys, users can attain complex syncopations and polyrhythms. If the app is synced to the tempo of a DAW or music playback, the user can perform good-sounding rhythms over any song that is personally meaningful to them.

The column layout leaves some unused keys in the upper right corner of the keyboard: “-“, “=”, “[“, “]”, “”, etc. These can be reserved for setting the tempo and other UI elements.

The app defaults to Perform Mode, but clicking Make New Kit opens Sampler mode, where users can import or record their own drum sounds:

- Keyboard shortcuts enable the user to select a sound, audition it, record, set start and end point, and set its volume level.

- A login/password system enables users to save kits to the cloud where they can be accessed from any computer. Kits get unique URL identifiers, so users can also share them via email or social media.

It is my goal to make the app accessible to users with the widest possible diversity of abilities.

- The entire layout will use plain text, CSS and JavaScript to support screen readers.

- All user interface elements can be accessed via the keyboard: tab to change the keyboard focus, menu selections and parameter changes via the up and down arrows, and so on.

Perform Mode:

Sampler Mode:

Mobile version

The present thought is to divide up the screen into a grid mirroring the layout of the QWERTY keyboard. User testing will determine whether this will produce a satisfying experience.

Prototype

I created a prototype of the app using Ableton Live’s Session View.

Here is a sample performance:

There is not much literature examining the impact of drum programming and other electronic rhythm sequencing on students’ subsequent ability to play acoustic drums, or to keep time more accurately in general. I can report anecdotally that my own time spent sequencing and programming drums improved my drumming and timekeeping enormously (and mostly inadvertently.) I will continue to seek further support for the hypothesis that electronically assisted rhythm creation builds unassisted rhythmic ability. In the meantime, I am eager to prototype and test QWERTYBeats.