I’m working with Soundfly on the next installment of Theory For Producers, our ultra-futuristic online music theory course. The first unit covered the black keys of the piano and the pentatonic scales. The next one will talk about the white keys and the diatonic modes. We were gathering examples, and we needed to find a well-known pop song that uses Lydian mode. My usual go-to example for Lydian is “Possibly Maybe” by Björk. But the course already uses a Björk tune for different example, and the Soundfly guys quite reasonably wanted something a little more millennial-friendly anyway. We decided to use Katy Perry’s “Teenage Dream” instead.

A couple of years ago, Slate ran an analysis of this tune by Owen Pallett. It’s an okay explanation, but it doesn’t delve too deep. We thought we could do better.

Here’s my transcription of the chorus:

When you look at the melody, this would seem to be a straightforward use of the B-flat major scale. However, the chord changes tell a different story. The tune doesn’t ever use a B-flat major chord. Instead, it oscillates back and forth between E-flat and F. In this harmonic context, the melody doesn’t belong to the plain vanilla B-flat major scale at all, but rather the dreamy and modernist E-flat Lydian mode. The graphic below shows the difference.

Both scales use the same seven pitches: B-flat, C, D, E-flat, F, G, and A. The only difference between the two is which note you consider to be “home base.” Let’s consider B-flat major first.

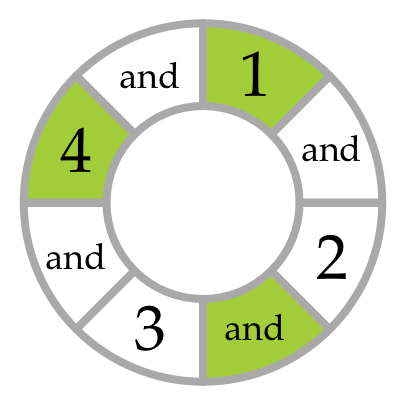

To make chords from a scale, you pick any note, and then go clockwise around the scale, skipping every other degree. The chords are named for the note you start on. If you start on the fourth note, E-flat, you get the IV chord (the other two notes are G and B-flat.) If you start on the fifth note, F, you get the V chord (the other two notes are A and C.) In a major key, IV and V are very important chords. They’re called the subdominant and dominant chords, respectively, and they both create a feeling of suspense. You can resolve the suspense by following either one with the I chord. The weird thing about “Teenage Dream” is that if you think about it as being in B-flat, then it never lands on the I chord at all. It just oscillates back and fourth between IV and V. The suspense never gets resolved.

If we think of “Teenage Dream” as being in E-flat Lydian, then the E-flat chord is I, which makes more sense. The function of the F chord in this context isn’t clearly defined by music theory, but it does sound good. Lydian is very similar to the major scale, with only one difference: while the fourth note of E-flat major is A-flat, the fourth note of E-flat Lydian is A natural. That raised fourth gives Lydian mode its otherworldly sound. The F chord gets its airborne quality from that raised fourth.

Click here to play over “Teenage Dream” using the aQWERTYon. The two chords can be played on the letters Z-A-Q and X-S-W. For comparison, try playing it with B-flat major. Read more about the aQWERTYon here.

“Teenage Dream” is not the only well-known song to use the Lydian I-II progression. Other high profile examples include “Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac and “Jane Says” by Jane’s Addiction. over the same chords. Try singing any of these songs over any of the others; they all fit seamlessly.

The chorus of “Teenage Dream” uses a striking rhythm on the phrases “you make me”, “teenage dream”, and “I can’t sleep”. The song is in 4/4 time, like nearly all contemporary pop tracks, but that chorus rhythm has a feeling of three about it. It’s no illusion. The words “you” and “make” in the first line are each three eighth notes long. It sounds like an attempt to divide the eight eighth notes into groups of three. This rhythm is called Tresillo, and it’s one of the building blocks of Afro-Cuban drumming.

Tresillo is the front half of son clave. It’s extraordinarily common in American vernacular music, especially in accompaniment patterns. You hear Tresillo in the bassline to “Hound Dog” and countless other fifties rock songs; in the generic acoustic guitar strumming pattern used by singer-songwriters everywhere; and in the kick and snare pattern characteristic of reggaetón. Tresillo is ubiquitous in jazz, and in the dance music of India and the Middle East.

“Teenage Dream” alternates the Tresillo with a funky syncopated rhythm pattern that skips the first beat of the measure. When you listen to the line “feel like I’m livin’ a”, there’s a hole right before the word “feel”. That hole is the downbeat, which is the usual place to start a phrase. When you avoid the obvious beat, you surprise the listener, which grabs their attention. The drums underneath this melody hammer relentlessly away on the strong beats, so it’s easy to parse out the rhythmic sophistication. Katy Perry songs have a lot of empty calories, but they taste as good as they do for a reason.