[This post is a draft of a section of a chapter that I’m supposed to be writing with Neil Myler on contextual allosemy in Distributed Morphology for the forthcoming Handbook of Distributed Morphology. Comments and corrections solicited!]

In Distributed Morphology, idioms have been characterized as contextual allosemy. “Allosemy” is the property of having multiple meanings, either related or unrelated; “contextual allosemy” involves the choice of one of these meanings in a particular context or environment. The discussion of idioms as contextual allosemy starts with observations from the literature about locality restrictions on idioms. Notably, “subject idioms” with an idiomatic subject and verb, but an open object position, are observed to be rare or nonexistent, as are passive idioms that are not idiomatic in the active. These observations suggest a VP-sized locality domain for idioms that excludes transitive subjects. As part of the general project to dissolve the word/phrase distinction, Marantz (1997) relates these observations to Miyagawa’s (1980, 1984) claim that lexical causatives can be idiomatic, while syntactic causatives in Japanese are never idiomatic. The leading idea here is that the locality domain for idiom formation might fall inside of a phonological word. The Japanese syntactic causative, although a word-sized unit, nevertheless cannot take on an idiomatic meaning as a whole because the relationship between the causative affix and the verb stem would cross a locality barrier, much like the way that the relationship between a transitive subject and the verb does.

(25) VP idioms with V-(s)ase (Miyagawa (1984: 190)

a. hana o sak-ase

flower ACC bloom-CAUS

‘to succeed’b. hara o her-ase

stomach ACC decrease-CAUS

‘to be hungry’

Marantz (1997) links these observations to the active voice node, which is a putative phase head in Minimalist Grammar. Such a node would separate the subject and a transitive verb, as well as the syntactic causative affix and the verb stem, which arguably contains active voice as well. The idea is that a phase boundary may occur within a word, as well as in phrases, and that phases mark the boundaries of lexical influence, such that idioms must be fully contained within a phase.

From the origins of this proposal within Distributed Morphology, any possible contrast between idioms and polysemy was blurred – “polysemy” referring to the property of having multiple related meanings, such as book the physical object and the intellectual property. Consider the title of a widely distributed paper addressing issues of stem suppletion, “‘Cat’ as a phrasal idiom” (Marantz 1995). The leading idea of the “Cat” paper was that all words, even apparently morphologically simply words like cat, decompose into at least a root and a category determining affix. The meaning of roots would always be determined contextually, within the domain of the first phase head up from the root. Calling cat a phrasal idiom, then, emphasizes both the dissolving of the word/phrase distinction and the assumption that idioms involve the same contextual calculation of root meaning as is involved in polysemy. That is, the connection between (fill the) bucket and (kick the) bucket might be parallel to that between (physical) book and (intellectual property) book.

What was missing from this early work, then, was any clear delineation among at least three possible relations between different meanings of the same phonological form: (accidental) homophonic, allosemic, and idiomatic. The two meanings of bat would, for the synchronic grammar at any rate, involve accidental homophony, the two meanings of book would involve polysemy and the two meanings of bucket an idiomatic connection. If these distinctions are real, linguistic theory should provide means beyond meaning intuitions to classify cases as one or the other. For the distinction between accidental homophony and polysemy, what’s needed is a theory of polysemy – what kinds of meaning relations are made available by grammars that might connect related meanings of the same root. Two apparent meanings of the same phonological form would involve polysemy to the extent that the relation between the meanings is analyzable within the theory of polysemy. What about the distinction between polysemy and idioms? Here, two possible generalizations emerge from the literature. First, idioms always involve a reading in addition to a possible literal reading, whereas in contextual allosemy, one reading may be forced. If there’s a bucket on the ground, you can always kick the bucket and spill its contents. However, although globe has related meanings of a sphere and the earth,global has only the earth reading. Second, when we’re considering the locality domain for interpretation, idioms seem to involve the relation between (at least) two roots, while allosemy may involve a root and a functional morpheme. Even in the case of the Japanese syntactic causatives, recent work by Yining Nie (2020) suggests that a root is involved for the causative affix in such constructions.

In an important and illuminating paper, Anagnostopoulou and Simiati (2013) present evidence from Greek adjectival participles to argue that the locality domains for idiom formation and contextual allosemy are indeed distinct, and that the domains correspond to the conflicting analyses of “special meanings” in Marantz (2001) and Marantz (2013). While active voice defines the domain for idioms, semantically relevant category determining nodes (n, v, a) create barriers for contextual allosemy. Anagnostopoulou and Samioti consider different types of deverbal adjectives formed with the suffixes –t(os) and –men(os). They argue that many –tos formations involve an adjective formed directly from a (semantic) root. With no barrier between the –tos affix and the root, these words can involve contextual allosemy on the verbal stem, with a special meaning triggered by the –tos not available for the verbal root as a verb.

(39) Stative –tos participles showing direct attachment of –tos to Rootevent

a. Verb sfing-o ‘tighten’

Participle sfix-tos ‘tight, careful with money’b. Verb ftin-o ‘spit’

Participle ftis-tos ‘spitted, spitting image’

Meanwhile, canonical –men(os) adjectives are built on semantically eventive v stems. Since the v intervenes between –menos and the root, –menos may not trigger special meanings not available for the use of the root as a verb. On the other hand, –menos adjectives may have additional, idiomatic readings not present for the verbal stem. For example, in (41), the –menos participle has either the literal meaning or the idiomatic reading, while the idiomatic reading is not present for the verb in its other forms.

(41) Eventive –menos participles

Verb trav-a-o ‘pull’

Participle trav-is-menos ‘pulled, far-fetched’

Finally, there are –t(os) adjectives with “ability/possibility” readings parallel to –able adjectives in English. The semantics of ability adjectives implicate active voice, and Anagnostopoulou and Samioti (2013) argue that there is additional morphological evidence indicating that the ability –tos adjectives are formed from a larger stem than the perfective –tos adjectives and –men(os) adjectives. For the ability –tos adjectives, no idiomatic reading is possible; any ability reading of the adjective is paralleled by a reading of the (transitive) verb.

(51) Ability –tos adjectives have no idiomatic readings

a. –menos trav-ig-menos ‘pulled, far-fetched’

–tos aksi-o-travix-tos ‘worth pulling’b. –menos stri-menos ‘twisted, crotchety’

–tos aksi-o-strif-tos ‘worth twisting’

The Distributed Morphology literature has presented evidence that idiom formation respects boundaries that may appear inside or outside of phonological words. This evidence supports the general thesis of DM that the phonological word is not itself a relevant constituent for syntactic and semantic principles that govern syntactic structure and meaning. However, the literature does not yet provide a comprehensive analysis of idioms or of polysemy, relying on generalizations in these areas that stand outside a general theory.

References

Anagnostopoulou, E., & Samioti, Y. (2013). Allosemy, idioms, and their domains: Evidence from adjectival participles. In Folli, R., Sevdali, C., & Truswell, R. (eds.), Syntax and its Limits, 218-250. Oxford: OUP.

Marantz, A. (1995). “Cat” as a phrasal idiom: Consequences of late insertion in Distributed Morphology. MIT: Ms.

Marantz, A. (1997). No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own lexicon. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 4(2), 14.

Marantz, A. (2001). Words. WCCFL XX handout, University of Southern California.

Marantz, A. (2013). Locality domains for contextual allomorphy across the interfaces. In Matushansky, O., & Marantz, A. (eds.), Distributed Morphology today: Morphemes for Morris Halle, 95-115. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Miyagawa, S. (1984). Blocking and Japanese causatives. Lingua, 64(2-3): 177-207.

Miyagawa, S. (1980). Complex Verbs and the Lexicon. University of Arizona: PhD dissertation.

Nie, Y. (2020). Licensing arguments. New York University: PhD dissertation.

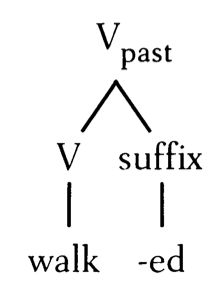

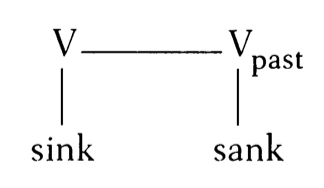

On the general line of thinking in these blog posts, a word like walked is morphologically complex because it consists of at least some representation of a stem plus a past tense feature (more specifically, a head in the extended projection of a verb). This is also true of the “irregular” word taught. Thus there is an important linguistic angle from which walked and taught are equally morphologically complex, whatever one thinks about how many phonological or syntactic pieces there are in either form.

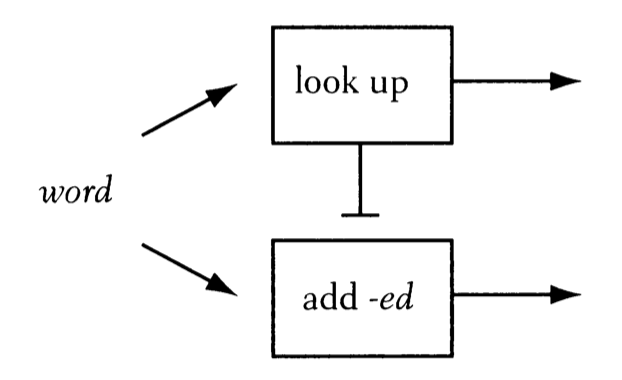

On the general line of thinking in these blog posts, a word like walked is morphologically complex because it consists of at least some representation of a stem plus a past tense feature (more specifically, a head in the extended projection of a verb). This is also true of the “irregular” word taught. Thus there is an important linguistic angle from which walked and taught are equally morphologically complex, whatever one thinks about how many phonological or syntactic pieces there are in either form. while the relationship between walk and walked is rule-governed, such that walked is not stored as a word and must be generated by the grammar when the word is used.

while the relationship between walk and walked is rule-governed, such that walked is not stored as a word and must be generated by the grammar when the word is used.