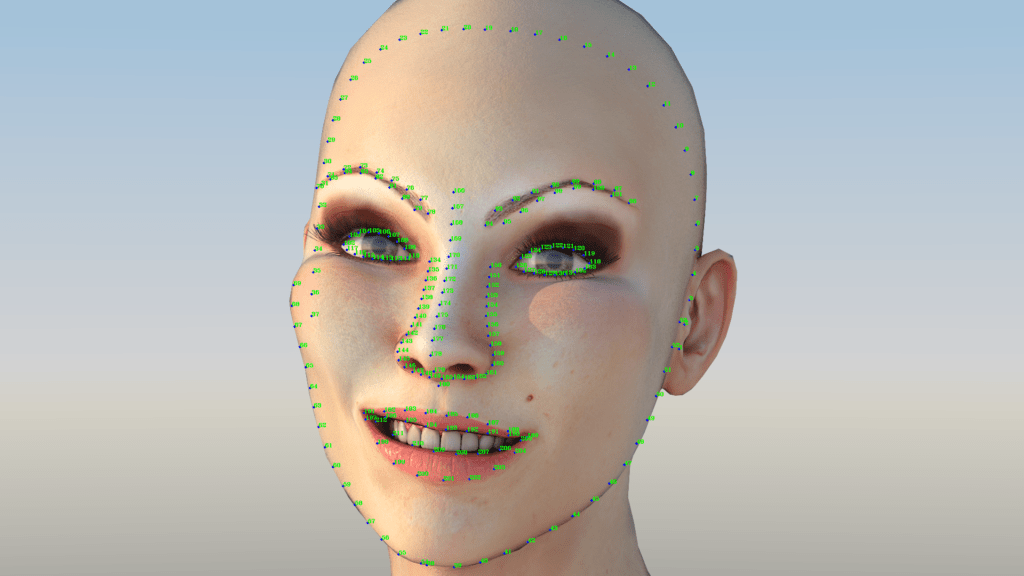

Nowadays, beautified camera apps have largely transformed our perception of beauty, especially to those who are addicted to social media and short-video platforms. As Benjamin Bratton argues, “Any surface is potentially a skin and its sensitivity is open to design.” We could both consider the AI system behind the apps and the interfaces of beautified cameras as a skin. AI systems embedded in these products capture and learn the “characteristics of beautiful faces” through constantly reading numerous human faces. But the problem is that, although AI seems to be an object without subjectivity and gathers objective facts, it is actually shaped by human, with either explicit or implicit cognitive bias.

The subjectivity of AI could further be deepened with our biased cognition and “teaching”. Beautified cameras are inclined to “standardize” our cognition of beauty and eventually, narrow it. There was a period of time when users were overly beautified and their faces look distorted—overly v-shaped faces and big eyes—in those cameras, but now, as users are allowed to manually adjust the angle of their eyebrows, the height of their nose bridge, the width of their forehead, etc., their activities on these apps turn into user data which is further learnt by machines. As a result, today’s beautified cameras are both closer to the mainstream aesthetics and more natural, hardly showing modification.

“The flexibility and ubiquity of sensors is a function of the platformization of components and sub-components across applications, and the distribution of the same or similar sensors across surfaces means that different kinds of bodies share the same sensory systems.” AI systems behind beautified cameras, seen as powerful sensors, have been applied to various applications over time. For instance, beautification is now widely used in short-video platforms like Douyin and Kuai, and makeup recommendation apps. It is said that “it seems that there’re so many beauties and handsome guys on these social media platforms, but why can’t we find them in reality?” Beautification on one hand greatly blurs the boundary between virtual and reality, evolving the illusion that people would look exactly the same as those on social media, on the other hand encourages the mass to judge whether a person is beautiful or not with models of beautification. AI profoundly changes the way we look at appearance. It’s not astonishing that in contemporary China, those who have delicate small faces with bigger eyes and lighter skin are more likely to be chased after and become profitable influencers.

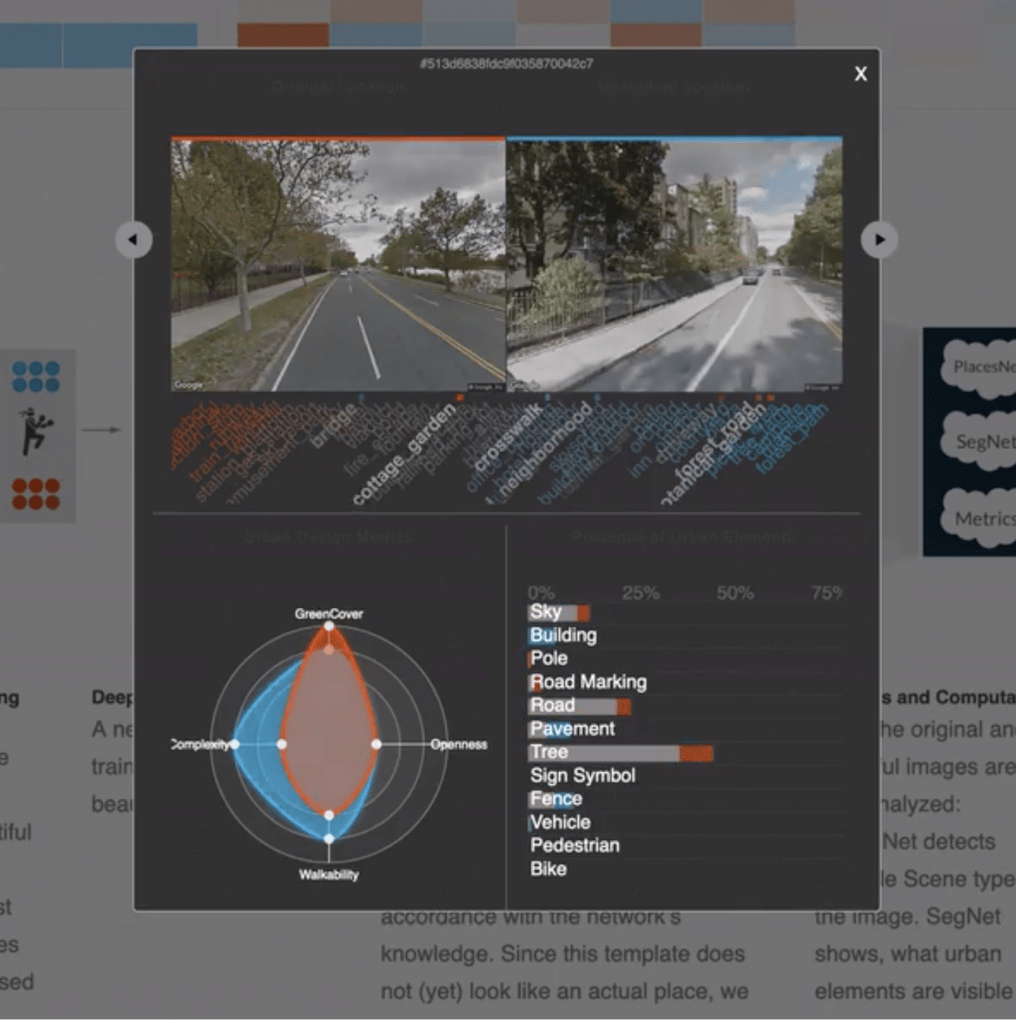

Beautification has not only applied to human faces, but also exert its influences on city-planning. UK researchers have trained AI to recognize beautiful scenery using deep learning. (https://www.wired.co.uk/article/ai-learns-the-meaning-of-beauty) They first processed 2 million images and labelling them with information on what landforms are on the pictures, then explored what attributes rate higher according to a large database (somewhat subjective). It is not surprising that images containing natural features with historical architecture gained higher scores, yet interestingly, scenes with open expanses lowered the score. How the AI system thinks is inextricable from how it senses. If the machine is taught by the database that valleys, beaches, and church deserve appreciation, while grassland and athletic fields are looked down upon, it isolates the connections between different landforms, which may contribute to harmonious landscape, and rate a scene unfairly.

The rating was further developed into an emerging technology and AI nowadays is likely to help design the landscape of a city. Yet as the rating may transform our perception of beauty and we growingly rely on AI, the designs provided by AI can be abrupt and inhumane.