“This is Dragonfly. Dragonfly has 28,000 eyes, blinking 40,000 times per second.”

– A robotic AI voice-over (Dragonfly Eyes, 2017)

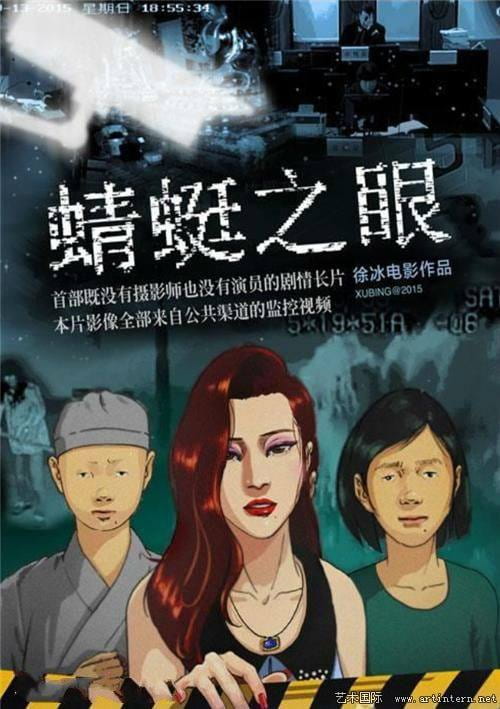

Dragonfly Eyes is an experimental feature film directed by Xu Bing, one of China’s most esteemed contemporary artists. In the film, Xu uses fragments of reality and recycles a found visual language to tell a fictional story. Without a cameraperson or an “actor”– rather, it was created solely by downloading more than 10,000 hours of publicly accessible video surveillance footage, many from Chinese live-streaming sites. Then the footage were compiled, edited, and dubbed into a relatively coherent storyline with a narrative of stranger sociality. The 81-minutes film is believed to be the first one to combine the technologies of over 245 million global surveillance cameras and cloud computing, turning out to become a technological spectacle itself.

The name “Dragonfly Eyes” is a metaphor of the saturated surveilling cameras, just like a compound eye with a cavalier perspective. It is well known that surveillance capacities can be massively augmented by information technology, which resonates with the point that infrastructures can act as force amplifiers for the human bodies. For China’s case, Skynet tracks more than twenty million surveillance cameras; it can identify a person in seconds and is used to provide real-time security updates; Sharpe Eyes, a nationwide system, connects private and commercial cameras to a centralized database. The public surveillance cameras, along other high-tech digital tools to record, track, monitor, and influence the behavior of 1.4 billion individuals, such as GPS monitoring, advanced facial recognition software, and artificial intelligence, constitute an extensive surveillance media infrastructure in the post-socialist China, a reality of our new virtual information transparence.

Stripped of its unconventional form of artistic representation, Dragonfly Eyes is a classic romance story about self-identification in essence. To be more specific, the story illustrates a kind of visible absence, and anonymity under the panoptic power. In the first half, we follow the composite “protagonist,” Qing Ting (which means exactly “dragonfly” in Mandarin), as she leaves the Buddhist monastery where she’s been grown up from a child to take up a series of low-paying jobs in the city as a “grassroot”. She first finds work at a dairy farm, where she is spotted by Ke Fan, the “male savior”, on the closed-circuit system that monitors its employees. After she’s fired from the dairy farm, Qing Ting takes a job at a dry-cleaning business and, later, at a restaurant. Then the turning point of her life comes: one day on the way home from work, she passes by a plastic surgery clinic and gets offered a special discount. Having been suffering from adversity and instilled with the common idea that physical beauty is crucial especially for women in today’s society, Qing Ting takes a chance to get the plastic surgery as an attempt to gain social mobility.

Screen Stills of Dragonfly Eyes

Screen Stills of Dragonfly Eyes

Paradoxically, we don’t really know what Qing Ting looks like in the first place, not to mention who she has become after she changes her face. Therefore, the second act of the film is narrated by Ke Fan, who holds the same uncertainty of Qing Ting’s whereabouts as he has been in jail for several years. The story veers toward absurdist parable. After investigation, Ke Fan is convinced that surgery has turned Qing Ting into Xiao Xiao, a popular online host. Because of her ridicule of another celebrity’s looks in a live broadcast, Xiao Xiao becomes the target of a toxic online hate campaign that pushes her offline and, it seems, to suicide. Here Xu reveals the absurd reversal of public emotion that feels sorry for the scandalized girl’s falling with a presumption of her death, which as well is often the case in real life.

Then the story comes back to the point of surveillance when the police are looking for as a missing person. The fact is that they cannot even identify Xiao Xiao for there are so many similar “plastic faces”. “That Xiao Xiao is turning up everywhere,” one police officer says. “If we can’t tell them apart, what chance do surveillance cameras have?” Confronted with the new reality that appearance is no more fixed, the camera-eye shows its very limit for reliance on visibility. It is this epidemic of virality that finally overwhelms the state’s surveillance apparatus and fundamentally challenges the notion of “epidermalization.”

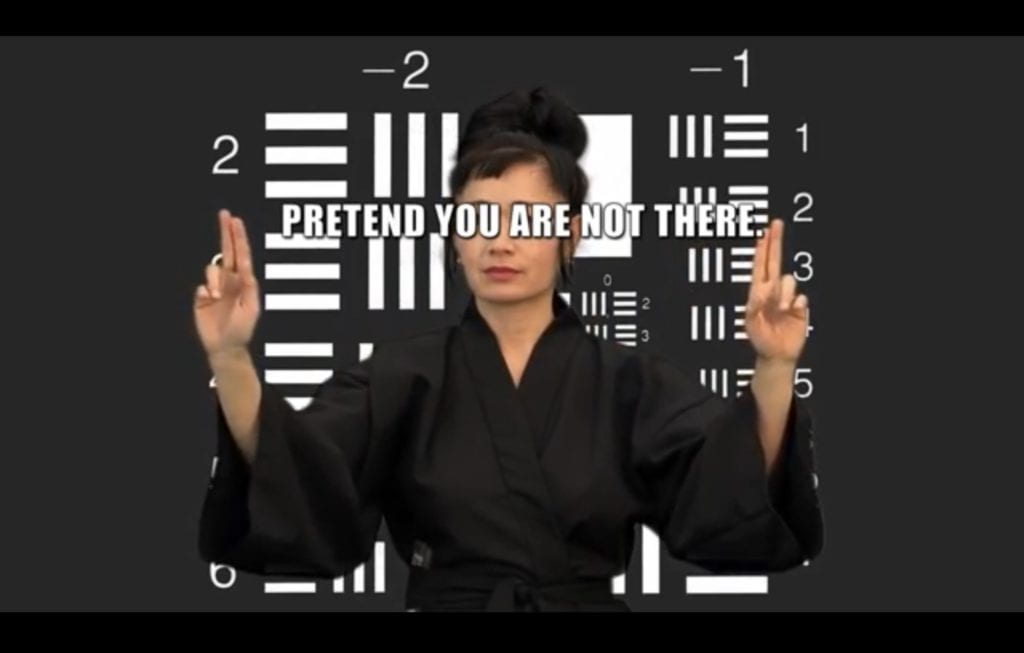

The weird strategy of resistance presented in the film reminds me of the five lessons in invisibility Hito Steyerl offers in her short video work How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational MOV File (2013). Advanced face-lifting technology may be another means of “seeping out” to envision in such an age of over-visibility. By changing appearance and resembling each other in reference of a standard model, body becomes a replicable iconic symbol. In other word, images use our body as a visual medium in the simulacra process. It is a reiteration of the current prevailing phenomenon, that new technologies of vision have introduced a certain abstraction in our visual experience, as we no longer are able to control the relation existing between an image and its model. Thus individuality is erased for identification under the visual surveillance system.

Screenshot of How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational MOV File

From a policing point of view, no matter the digital camera eyes are “panoptic” or not, the illusion of omniscience is almost as effective as the real thing for its imperceptible and uncertain characteristics: You don’t need to watch everyone if you can get everyone to behave as though they are being watched. However, actually Chinese citizens’ relationship to surveillance is not totally passive and repressed by the central state. Xu contended in an interview with WSJ: “Our understanding of surveillance for the most part is control, management, and supervision… But now it’s expanded from the government to everyone.” The government’s digital infrastructure is merged with social media, residential cameras, and commercial surveillance systems to create and disseminate surveillance data as a social collusion, a consensually-based control, and a normalized discipline.

For citizens, on the one hand, they embrace the technological prosthesis and entertain to surrender our privacy in order to tap into social networks, consumer convenience, and a sense of security; on the other hand, they are burdened with fears and anxieties about electronic surveillance. The expository habits not only make us vulnerable to punishment but also shape new pleasures, identities, and desires. In terms of the citizen-generated data, “prosumers” consume surveillance data they produce and produce new content while consuming those data in and through the digital mediascape. Therefore, the infrastructures of electronic surveillance does have panoptic potentiality, but it is less like a dichotomy of centralized or decentralized power, than a complicated in-between status.

Leave a Reply