Every time I talk about the people who are deeply influenced by their hometown flavor, or mention regional characteristics of food, I would come up with the following example that happened around me:

When I was an undergraduate, I had a classmate from Hunan province where the diet is always spicy. She just came to Shanghai and felt very uncomfortable about the food offered in the canteen. As a result, she lost 3 kilos a month. She complained that the food in Shanghai is too sweet for her to swallow. Even the food in the canteen, where, to the greatest extent, the tastes of students from various regions are taken into account, is still preserves a strong Shanghai style. Therefore, she asked her mother to send two jars of chopped pepper from her hometown, and mixed it with rice, soup, even “sweet and sour pork ribs”, almost anything she ate. The chopped pepper worked up her appetite, and she said “ That is what real food should be!”

It seems that for most Chinese, the taste of hometown carries much more meaning than the food itself, which is called culinary nostalgia in Mark’s text. He points out that “regional food culture was intrinsic to how Chinese connected to the past, lived in the present, and imagined a future.” We can explore this phenomenon by tracing the evolution of the word “weidao (taste)” meaning in Chinese.

It is not until 1916 that Taiyan Zhang use this word “weidao” to describe the taste and flavor of food. Before that, this word, in fact, had extensive meanings, including the ways people processed food and cooked, the people’s attitude towards food, etc. Simply put, it refers to the relationship between people and food, and the story of people and food, where the meaning of culinary nostalgia was implicitly embed. It stressed the relationship between people and the nature of food. Regarding this point, there’s a new documentary called Taste Of China released recently. I think it should be more accurately called “the source-tracking journey about Chinese food”, since “food source” is the core of this documentary.

That is, traditional Chinese emphasize a lot on the raw materials of food. Take me as an example. I was born in a coastal city in Jiangsu Province, and the gourmets there, like my father, have very strict requirements for ingredients, especially seafood. They can know whether the fish is wild or reared with one bite, and even where the fish was caught in the Yangtze River since the water quality in different regions is diverse, which contributes to the difference in the texture of fresh fish.

However, our generation, who grown up in industrial age, is surrounded by air pollution, soil pollution, off-season fruits and vegetables, genetically modified food, etc., which makes us lose the sense for “food source”.

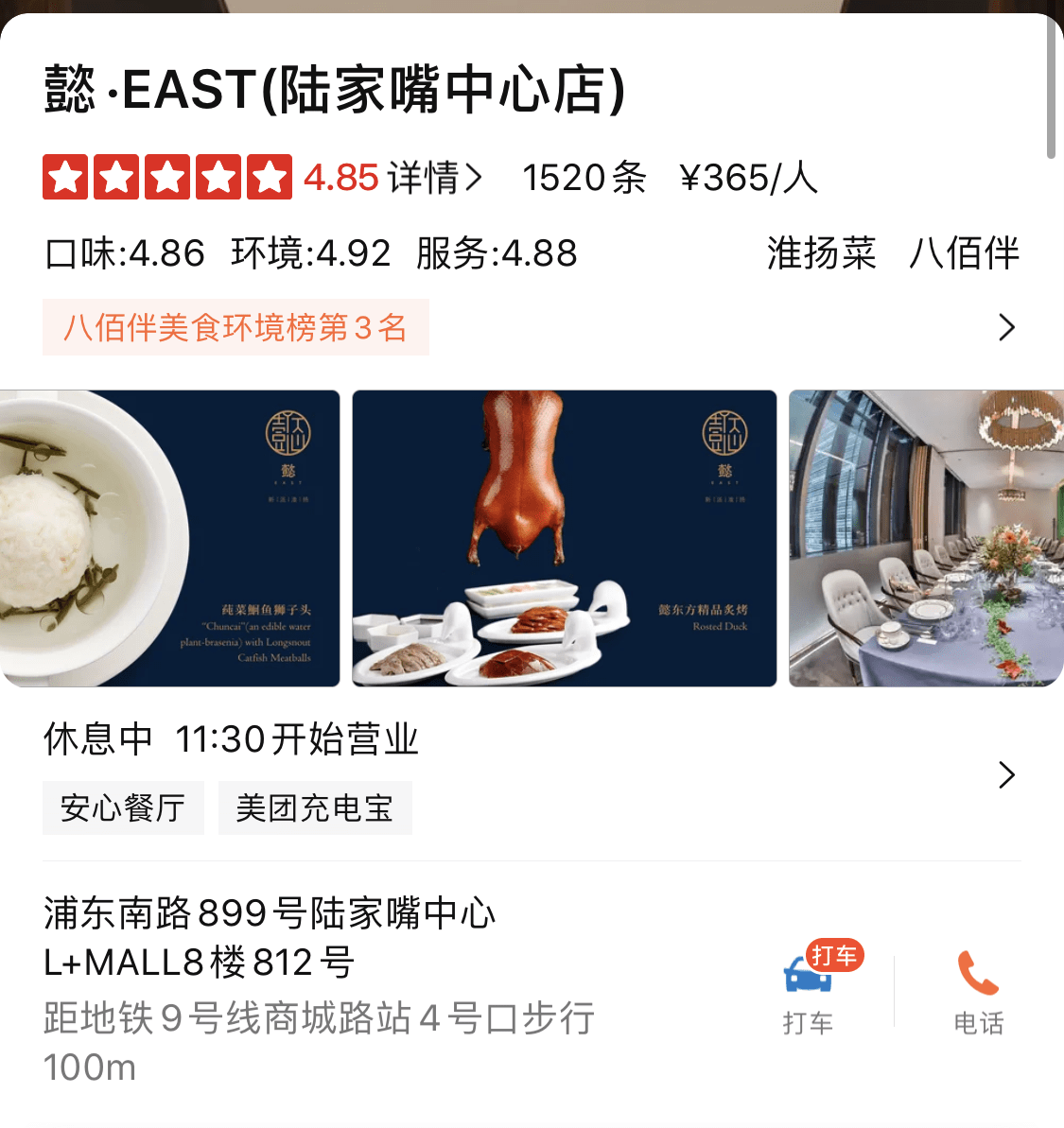

We can see this trend also in the cities’ restaurants. Strictly distinguished“eight major Chinese cuisines” in the traditional sense no longer exists. You can easily find fish-flavored pork shreds at a Shandong restaurant, and you can eat roast duck at a Huaiyang restaurant. These restaurants, in fact, are moving towards a trend of integration.

From the perspective of customers, we can observe that young people increasingly favor fusion restaurants because they can eat different flavors of food from all over the world, even the combination of Chinese and Western recipes. Except for those famous dishes, it seems difficult for contemporary young people to exemplify their hometown flavors. The boundaries are getting blurred. Therefore, I’m not so sure that what effects this trend will have on future regional identity.

Fusion Restaurants are high-graded.

Will it be the only way to recall the taste of your hometown in small stalls along the street exclusively ? More important, will the young in cities be able to recognize their hometown flavor?

Leave a Reply