Author: Brendan Hogan

This being the first iteration of a course co-taught by an economist (Dr. Johann Jaeckel) and a philosopher, that it was a paired course between London and NYC, and that, as a Global Topics course, it was populated by first year students in London and sophomores in New York, all presented various challenges. This post reflects on the perspective of the philosopher in London.

Perhaps most relevant to the question of politics in the classroom for the course ‘Critiques of Capitalism’, I found it very fruitful to approach the topic by providing students with the conceptual tools of the fact/value distinction. Very briefly, the fact/value distinction as it is discussed in philosophical and philosophy of science circles, emerges with the scientific revolution and the overthrow of the Aristotelian scientific paradigm. Science, done right, eliminates all religious, subjective, emotional, and particular elements through a method that is universal and objective. There is no underlying purpose or telos to natural motion and thus no way to read off of natural phenomena a link between what is the case to what ought to be the case. Natural science from this perspective famously eliminates biases, prejudices, and particularities of nationality, identity, and language in favor of value-free and verifiable results and propositions that are beyond the scope or ‘contamination’ of ethical values.

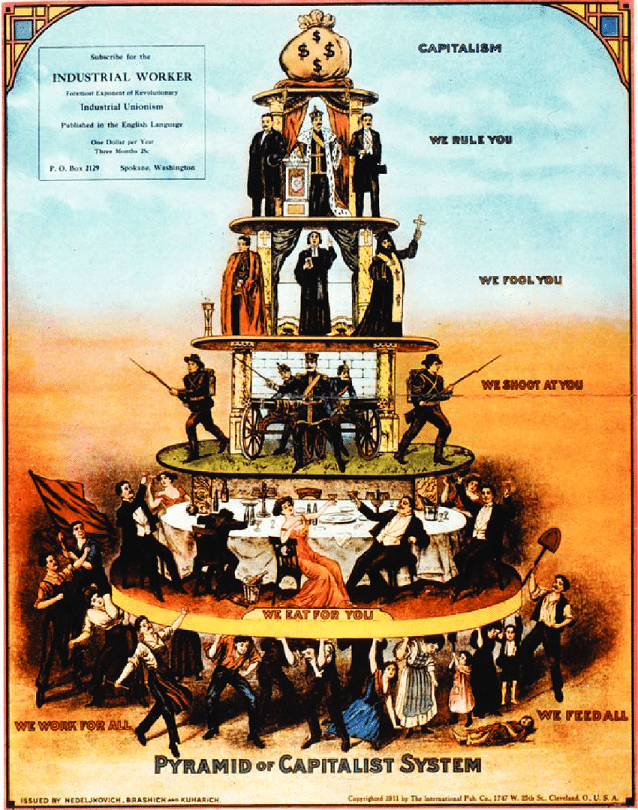

That the course was entitled ‘Critiques of Capitalism,’ then, places it already within a certain universe of economic and philosophical discourse given our respective disciplinary specializations that belies a complicated take on the distinction between facts and values to which I will return. In addition, however, it also puts the course itself in the first instance in the sphere of an immediate critique of the social order itself. In this sense it is a bit different than some other courses that take other axes of analysis that also focus on social oppression and domination as their object of inquiry.

That is to say, if one were to compare the frame for the course with other courses similarly interested in diagnosing social pathologies using such terms as ‘white supremacy,’ sexism, heterosexism, colonialism, or imperialism, a course on ‘capitalism’ differentiates itself because even given the critical modulator in the title, the subject-‘capitalism’-has been predominantly cashed out as a value neutral term, or perhaps as an honorific term, unlike the other terms used to describe social pathologies mentioned above. It still means something normatively different in our society to be pro-capitalist than it does to be a sexist, racist, or homophobe. And it is precisely this state of affairs that critics of capitalism challenge. Thus, the stakes of whether or not one can offer a ‘value-free’ description of the workings of capitalism on par with a natural phenomena such as the movement of Jupiter are quite high.

Certainly while the noticeable increased volume of voices in our public sphere that slide what is acceptable to say publicly ever further towards the gutter, it is still the case that there is a separation between the ‘factual’ vocabulary of capitalist economics, and the ‘evaluative’ vocabularies that attend descriptions such as ‘racist’ ‘sexist’ or ‘homophobic.’ Yet, it was precisely this difference that several of the critiques we taught ultimately wanted to problematize. And with this, the classroom became much more political. That is, it became clear, and somewhat uncomfortable for my students to realize that in fact, the stance you took on the system itself reflexively indicated whether or not you would be able to write a paper comparing, for instances ‘the virtues and vices of capitalism.’ Think for instance of some of the more trenchant critiques coming out of the Marxist humanist tradition or in fact the more recent statement of Pope Francis. To compare and contrast such virtues and vices in capitalism, from those perspectives would be no different than if you compared and contrasted the virtues of, say, slavery, or patriarchy.

Capitalism as a term of social discourse, and certainly its concomitants ‘class’, ‘exploitation,’ and of course ‘surplus value,’ were notoriously absent from popular media for decades, and while Millenials do seem to have some concrete attitudes about capitalism, it was not really a basic term of the United States’ popular descriptive vocabulary or a pillar of common conversation in the media. At least not until the Sanders campaign and the last nine years of post-great recession politics and the Occupy Movement. Indeed during the Cold War the opposing concept to communism was not capitalism but rather ‘the free market system’ as a stand-in for the social reality of a capitalist system. That Adam Smith demonstrated that free markets cannot survive under a capitalist mode of production was not often invoked alongside his ever-present metaphor of the ‘invisible hand’ in the pages of our business and political press. That is to say, that while ‘economy’ looms large and questions about economy are hugely present, some might say ‘hegemonic’ in our media, elections, and public discourse (and even our social sciences and intellectual practices), the particular economic order itself is not highlighted as a historically contingent phenomena, or at least as a human constructed phenomena. Rather, it is seen as the most natural expression of human nature.

Self-described orthodox economists have been publishing macro and micro economics textbooks for a long time without ‘capitalism’ being the subject of more than passing mention. To insist that capitalism was a fundamental explanatory category of the social world was to already locate oneself in a particular location on the political spectrum. So, one of the difficulties but intensely interesting aspects to exploring the critique of capitalism with students, lay in this background work highlighted by the authors we read. This is distilled in Marx’s famous comment when questioned about his particular moral beliefs, ‘Morality, what is that?’ A lot of work then was done at the level of how we understand the claim of some of the thinkers to scientificity, or to being a value free description of the workings of capitalism and not a normative or political stance. So, part of what I find to be most challenging is creating a space where students gain some distance to this value free description of the social sciences, without reducing social scientific descriptions to mere ideology or propaganda. It is a challenge looming large outside the classroom as well.