This piece was originally published in Marsyas: Studies in the History of Art,

Volume XVI, 1971-1973

RICHARD E. STONE

![]()

Tullio Lombardo’s Adam from the Vendramin Tomb: A New Terminus Ante Quem

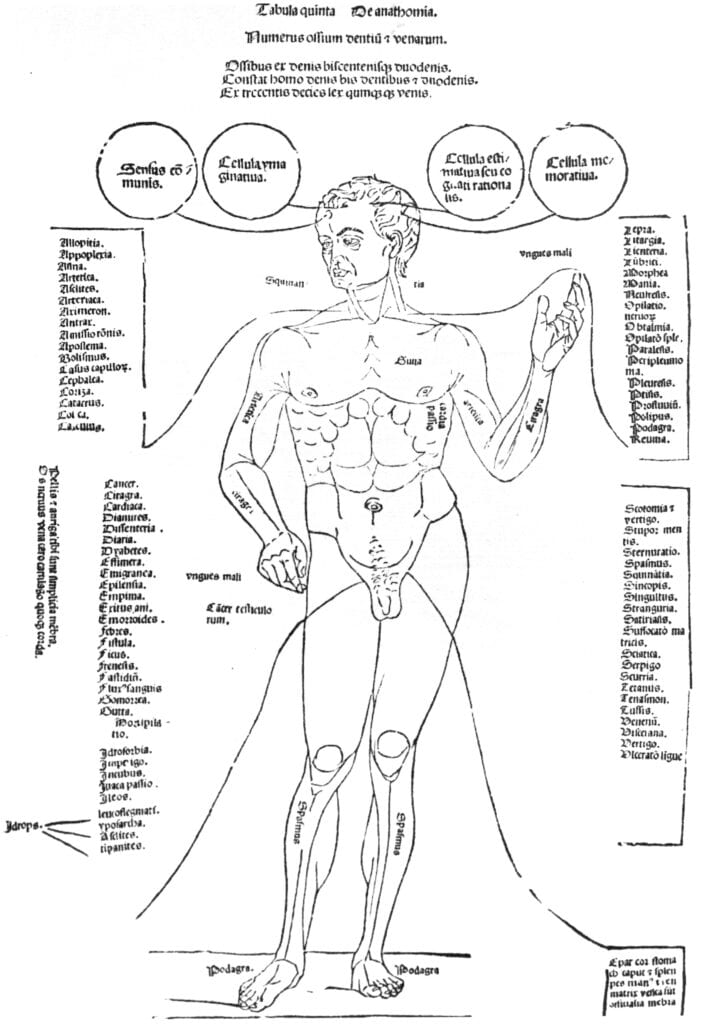

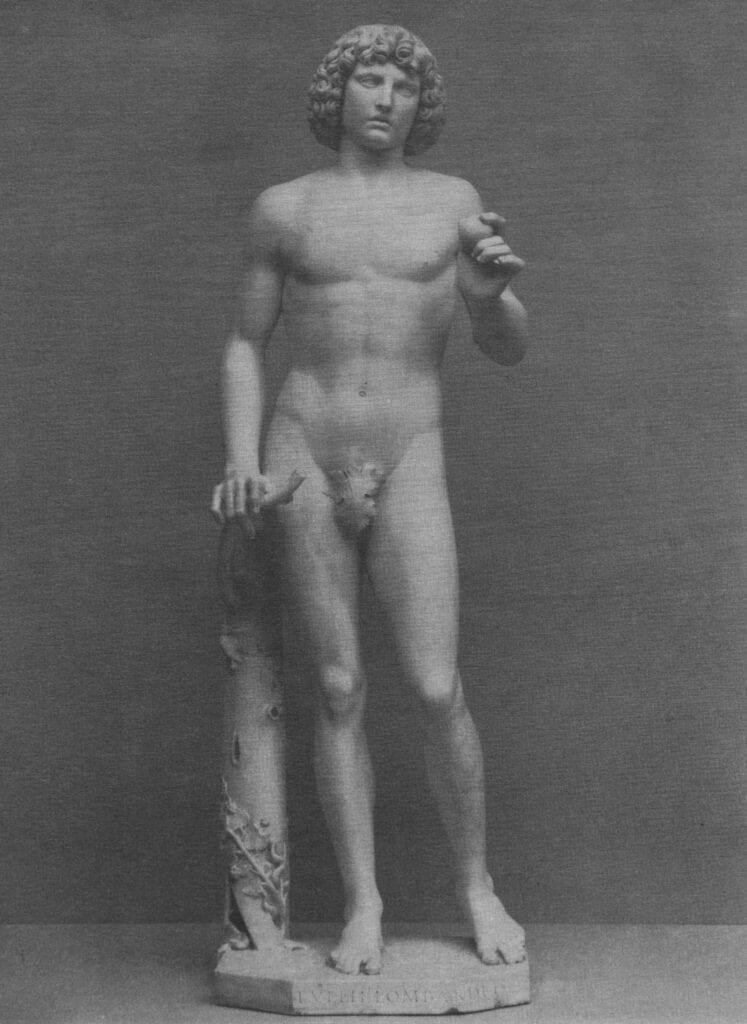

On July 26, 1491, the Venetian press of Johannes and Gregorius de Gregoriis issued the Fasciculus Medicinae, a popular medical compendium by Johannes de Ketham.1 The book, one of the pioneers of printed medical illustration, contained six woodcuts; one of these was a standing male nude captioned “Tabula quinta De anathomia, (fig. 1). We hope to show that this figure is crucial for the dating of Tullio Lombardo’s Adam from the tomb of Andrea Vendramin (fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Johannes de Ketham, Fasciculus Medicinae, Venice, 1491 (“Tabula quinta De anathomia”): Disease Man.

Fig. 2 Tullio Lombardo, Adam, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fletcher Fund, 1936).

The 1491 edition was evidently quite successful since a new edition emerged from the same press on February 5, 1493, more veneto, (i.e., 1494). The work was translated from Latin into Italian for the new edition, titled Fascicolo di Medicina,2 and the illustrations were almost entirely refurbished in the new classical style. With one important exception, all of the old blocks were recut and four entirely new blocks were added showing scenes of contemporary medical life.3 The only block to survive the renovation of the illustrations, the “Anathomia” we have reproduced, was also the only block of the first edition designed in the same classical style that is evident in the second.

What accounts for the classicism of this one block in the first edition? The manuscript examples of such medical illustrations are normally highly schematized, even diagrammatic, and depend on a very conservative medieval tradition.4 They never show the human body in a pose even remotely resembling a classical contrapposto but instead wit a rigid and symmetrical frontality. Indeed, the other illustrations in the first edition demonstrate this type. The classicism of the “Anathomia” block cannot therefore have originated in the medical illustration but must have in some way been inspired by the contemporary upsurge in Venetian classicism. In fact, it seems likely that the specific inspiration was the great new monument of Venetian classical taste, Tullio Lombardo’s Adam. This statue, one of the truly revolutionary representations of the standing male nude in Italian sculpture, seems to have made a profound impression on the artist of the woodcut. We believe that a comparison of the illustration to the statue will demonstrate this clearly, and that consequently the Adam must date before the first edition of the Fasciculus Medicinae.

Both the “Anathomia” woodcut and the Adam represent standing male nudes with similar vertical proportions. Each figure is almost exactly seven and one-third heads tall. In both cases there is precisely one head from the level of the chin to the level of the nipples and likewise one head from the level of the nipples to the navel. The only conspicuous discrepancy is in the upper legs, where the illustrator somewhat shortened the distance from hip to knee.

In adapting the Adam the illustrator deliberately reversed the position of the upper half of the figure in his drawing so that upon printing the arms would appear in the same position as in the statue. He nevertheless neglected to reverse the hips and the legs, thus changing the whole rhythm of the stance. Despite this alteration, the similarity of the two poses is quite striking.

Of course, the draftsman had to make certain other changes in the process of adapting the model to the purpose of medical illustration. The fig leaf and apple are gone, and so are the supporting stump and branch. He has also raised the left arm further so as to expose more of the underside of the forearm and, more importantly, he has greatly increased the definition of the musculature towards obvious, albeit stylized, anatomical ends.

The utter dissimilarity of the heads is perhaps the most noticeable difference between the statue and the woodcut. The head of Adam, wreathed in heavy curls, is almost frontal; the head in the woodcut has short hair and is sharply turned to the right. Again, this variation would seem to reflect the nature of the medical illustration. The four circles above the head

in the woodcut contain labels describing the supposed intellectual properties of the cerebral ventricles. In similar illustrations of the cerebral ventricles, the head is shown in the same three-quarter view as the woodcut, but with the actual ventricles of the brain exposed.5 Our artist has happily contented himself with merely indicating the positions of the ventricles by means of lines drawn to the surface of the cranium. The Adam’s great mass of hair and almost frontal face would have interfered with even this limited illustrational aim.

It has generally been recognized that despite Tullio’s close study of ancient sculpture, his Adam is based on no one classical prototype, but represents instead a unique combination of various sources.6 Thus, the close similarity of the woodcut to the Adam in both pose and proportion is unlikely to have been the result of both artists copying the same source.

We must therefore conclude that the artist who designed the woodcut certainly saw Tullio’s statue, and consequently that the Adam from the tomb of Andrea Vendramin was completed before the date of publication of the Fasciculus Medicinae—July 26, 1491.

Endnotes

1 Karl Sudhoff, Charles Singer, The Fasciculus Medicinae of Johannes de Ketham Alemanus. Facsimile of the first Venetian Edition of 1491, (Monumenta Medica, vol. I, ed. Henry E. Sigerist), Milan, 1924.

2 For the most recent facsimile of the 1493/4 edition see Johannes de Ketham, Fasciculo de Medicina, ed. Enzo Bottaso, Turin, 1967.

3 André Blum, “Le ‘Fasciculus Medicinae’ de Johannes Kétham” Byblis, vol. V, 1926, pp. 95–98.

4 For the medieval tradition see Robert Herrlinger, History of Medical Illustration from Antiquity to 1600, New York, 1920, pp. 25 ff.

5 Walter Sudhoff, “Die Lehre von den Hirnventrikeln in textlicher und graphischer Tradition des Altertums und Mittelalter,” Archiv fur Geschichte der Medizin, vol VII, 1913, pp. 149–205.

6 For a recent discussion of the sources of the Adam see Wendy Williams Stedman Sheard, The Tomb of Doge Andrea Vendramin in Venice by Tullio Lombardo, Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1971, pp· 168–169, esp. n. 55, 56 , 5 7.