Ramey Mize

University of Pennsylvania

Abstract

Popular perceptions and aesthetic renderings of artificial light evolved apace with technological developments in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Electricity held especially rich symbolic potential to the Italian Futurists, for whom the electric light bulb constituted a self-image. Joseph Stella’s fateful encounter with the Futurists in 1912 would later help to launch his own career, kindling within the painter a fresh understanding of the aesthetic richness of America’s technologically-preeminent landscape. Indeed, the dazzling force of Coney Island’s emblematic lights preoccupies Stella’s inaugural, critically-acclaimed picture, Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1913–14). Created under the aegis of the artist’s newfound vision, Battle of Lights amps up the Futurist electric topos to an almost unbearable intensity. But how exactly did Stella represent such profligate refulgence, such vivid surfeit? There are no discernible lamps, no obvious glimmers or chiaroscuro; electric light in this rendition instead adopts the heterogenous, hard-edged forms of discrete, surging shafts, multi-hued prismatic shards, and gem-like studs to comprise a single spell-binding mosaic.

This paper will explore the ways in which Stella’s Battle of Lights crystallized under the twin influences of both a Futurist vision and American mass culture and will marshal artificial light as its central gauge. In particular, I will submit that Futurist theories of electric light’s pictorial proportions were more literally and extensively substantiated in the American technological landscape and that such congruity enabled Stella to formulate a more heightened visual rhetoric for electricity as a unique optical spectacle. Finally, I argue that these newly-developed light technologies, from massive arc-powered floodlights to minute incandescent bulbs, as well as the rising complexity of special lighting effects and design, played a critical, little-studied role in the aesthetic logic of Battle of Lights.

![]()

“The Violent Blaze”:

Electrical Illumination in Joseph Stella’s Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1913–14)

Introduction: A New Brilliance

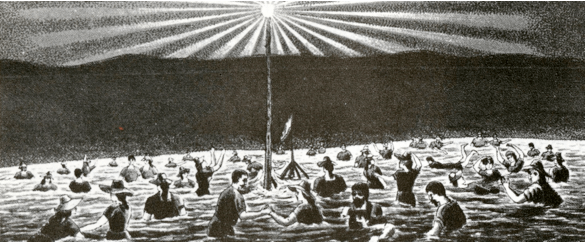

A late nineteenth-century print bears witness to a scene of peculiar recreation: a lively crowd of bathers wades through the gently lapping waves along the Coney Island peninsula, while, towering above them, something akin to a maypole burns brightly (Fig. 1).[1] This steely sentinel of aquatic revelry was, in fact, an electric “arc” lamp, and its vivid supply of outdoor illumination made possible the new nocturnal activity known as “electric bathing.”[2] Charles Brush introduced these arc lights to New York and the wider nation in 1880.[3] Eager to capitalize on the invention’s commercial potential, the entrepreneur and owner of Brighton Bathing Pavilion, William Engeman, installed the new device at the foot of his bathing bridge that same year.[4] Arc lighting, ranging from 500 to 3,000 candlepower, outshone gaslight by a vast margin, ushering in a groundbreaking quality and standard of brightness.[5] As the New York Herald observed of the new technology in 1882: “The dim flicker of gas, often subdued and debilitated by grim and uncleanly globes, was supplanted by a steady glare, bright and mellow, which illuminated interiors and shone through the windows fixed and unwavering.”[6] Compare, for example, the spectral glints of gaslights twinkling across the Thames in James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s Nocturne: Blue and Silver, Chelsea (1871) with the white-hot electricity from the arc lamp in the bathing print, which emits “powerful white rays” so distinct and “fixed” that they appear as solid forms, or brilliant blades cutting across the night sky.[7] It is evident that light, in its electrical manifestation, was understood here as a concentrated, almost concretized entity, in striking contrast to the hazy glow of gas.[8]

Fig. 1. Unidentified print, 19th century, reproduced in Rem Koolhaas’s Delirious New York (1978), page 36.

As this unlikely pairing demonstrates, popular perceptions and aesthetic renderings of artificial light evolved apace with technological developments. Electricity held especially rich symbolic potential to the Italian Futurists, for whom, as Peter Conrad has argued, the electric light bulb even constituted a “self-image.”[9] The founding members of the Futurist movement proclaimed their preoccupation in no uncertain terms in the “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting” in 1910: “The suffering of a man is of the same interest to us as the suffering of an electric lamp, which, with spasmodic starts, shrieks out the most heartrending expressions of color.”[10] A year earlier, their leader, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944), devoted an entire essay to the superiority and obliterative power of “three hundred electric moons” over nature’s original in “Let’s Kill the Moonlight,” published in Poesia in 1909.[11] Futurist artists, most notably Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916), Gino Severini (1883–1966), and Giacomo Balla (1871–1958), engaged this theme in a host of provocative canvases, many of which appeared in the Futurists’ seminal exhibition in February 1912 at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris.[12] Among the inflammatory installation’s attendees was the Italian-born, American artist, Joseph Stella (1877–1946).[13] Stella’s fateful encounter with the Futurists would later help to launch his own career, kindling within the painter a fresh understanding of the aesthetic richness of America’s technologically preeminent landscape.[14] In many ways, the United States, and specifically Manhattan, embodied the ideal Futurist landscape, a correlation that struck Stella full-force after his stint in Europe.[15] He wrote of this subsequent realization:

And when in 1912 I came back to New York I was thrilled to find America so rich with so many new motives to be translated into a new art. Steel and electricity had created a new world. A new drama had surged from the unmerciful violation of darkness at night, by the violent blaze of electricity, and a new polyphony was ringing all around with the scintillating, highly-colored lights.[16]

Among other hallmarks of modern, mechanistic life, the dazzling force of Coney Island’s emblematic lights animates Stella’s inaugural, critically acclaimed picture, Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1913–14), first exhibited at the Montross Gallery in New York City (Fig. 2). Created under the spell of the artist’s newfound vision, Battle of Lights amps up the Futurist electric topos to an almost unbearable intensity, as well it should; Luna Park, only one of three main amusement centers on the island, boasted well over one million electric lights by 1907.[17] The New York Times, in its evaluation of the canvas, marveled at the work’s electrical surfeit: “It is the largest canvas on view, and it is certainly the most brilliant. There is probably not a single Coney Island light that did not get into the picture.”[18] But how exactly did Stella represent such profligate refulgence? There are no discernible lamps, no obvious glimmers or chiaroscuro; electric light in this rendition instead adopts the heterogenous, hard-edged forms of discrete, surging shafts, multi-hued prismatic shards, and gemlike studs to comprise a single spellbinding mosaic. Stella produced a total of six Coney Island pictures between 1913 and 1918, and his long-term scrutiny of the site betrayed a deep-rooted interest in the intersection of design, technology, and sociology.[19] This essay will explore the ways in which Stella’s Battle of Lights crystallized under the twin influences of both a Futurist vision and American mass culture and will marshal artificial light as its central gauge.[20] In particular, I will submit that Futurist theories of electric light’s pictorial proportions were more literally and extensively substantiated in the American technological landscape, Coney Island in this case, and that such congruity enabled Stella to formulate a more heightened visual rhetoric for electricity as a unique optical phenomenon. Finally, I argue that these newly-developed light technologies, from massive arc-powered floodlights to minute incandescent bulbs, as well as the rising complexity of special lighting effects and design, played a critical yet little-studied role in the aesthetic logic of Battle of Lights.[21]

Fig. 2. Joseph Stella (1877–1946), Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1946), 1913–14. Oil on canvas, 77 x 84 3/4 in (195.6 x 215.3 cm). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT.

Electric Light as Futurist Muse

It is not insignificant that the Futurists first beheld electric light on a grand scale in Paris, the very place where Stella would later observe the extent to which la Ville Lumière had influenced their aesthetic. Heinz Widauer claims that Paris “must literally have electrified Boccioni and Severini” when they arrived in 1906—unsurprising, given that the city had served as the site for both the International Exposition of Electricity in the fall of 1881 and the Exposition Universelle of 1900, events which championed major advancements in the realm of electrification, including but not limited to illumination.[22] Electricity also made an impression on the artists’ mentor and instructor, Giacomo Balla, who had visited France six years earlier.[23] By this point, Paris would have been thoroughly radiant at night, a result of innovations in voltaic arc lighting made first by Sir Humphry Davy earlier in the century, and then refined by the Russian inventor Paul Jablochkoff, who introduced the original arc lamps along the Avenue de l’Opéra in Paris in 1878.[24] These lights generated a luminosity of such acute brilliance that it eventually became clear that they should be hung well above human height so as to avoid temporarily blinding pedestrians.[25] In short, as Ernest Freeberg makes clear, “The light thrilled, but pained.”[26] It was to this precise brand of lighting technology, as well its disorienting, luminous flood, that Balla dedicated almost an entire canvas, entitled simply Street Light (c. 1911, dated on painting 1909).

Like many early Futurist works, Street Light showcases a modification of the Italian painting technique known as Divisionism, a style which emerged around the same time as Neo-Impressionism in France.[27] In response to contemporary optical and color theories, such as those set forth by the American physicist Ogden Rood (1831–1902), Divisionists in Italy sought to amplify the vibrational radiance of their work through the application and juxtaposition of pure pigments in a multitude of expressive strokes.[28] Divisionism appealed to the Futurists both for its political and scientific directives, and for its aim to transmit subjective perceptions into a dynamic, aesthetic whole.[29] In “Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto,” the authors touted Divisionism as an essential component of their artistic approach, primarily for its enactment of an “innate complementariness” which elucidates the polarities and friction intrinsic to a modern world.[30]

Balla orients the glass bulb in Street Light slightly below a crescent moon; the lunar body, although visible, is almost smothered by the brutal scope of artificial light. The artist may have been working in direct response to Marinetti’s rhetorical vendetta against moonlight and call for “electric street lamps, with their thousand stabbing points.”[31] The painting may also have been a visual pun on the arc lamp’s common characterization as an “electric moon.”[32] The rays cast by the lamp assume a forceful presence rather than a benign gleam, very much in keeping with the true ruthlessness of the arc’s blaze. Balla’s divisionist marks take the form of innumerable, variegated “hooklets” which beam outward from the central light source in feverish waves, conveying an acute impression of the lamp’s inordinate voltage and blistering heat.[33] The shape of these chevrons could not have been arbitrary, and was more likely the result of attentive observation: the arc light derives its name from the arch-like formation of the lamp’s electric current, conducted and maintained across two slightly separated carbon rods.[34] While preparing for the painting, Balla spent a great deal of time in Rome’s Piazza Termini, a public space made vivid by many such lamps. As Thomas Cole has suggested, Balla may have been inundated with optical afterimages of these blinding arcs, later proliferating their ghostly hooks into a Divisionist torrent in the final picture.[35]

Although Balla did not exhibit Street Light in the 1912 Futurist exhibition in Paris,[36] the painting was nevertheless featured in the associated catalogue and exemplified the ways in which the Futurists translated individual psychosomatic experiences of modern culture into an equally modern literary or pictorial framework.[37] In other words, the Futurists built upon literal traits of “mechanical muses” or emerging technologies—in Balla’s case, the “arc” of the arc lamp—to craft their own visual language, evocative of a supremely mechanistic world order.[38] Boccioni also pursued graphic representations of the arc’s shaft-like illumination, with a special focus on its penetrative and divisive effects. In his painting The Laugh (1911), displayed in the Bernheim-Jeune installation, these luminous beams play a central compositional role. Shortly thereafter, Boccioni defined light’s role in the Futurist aesthetic in his book Futurist Painting and Sculpture (1913): “Often, a light, whether it be a ray from the sun or from an electric lamp, intersects an environment with a preponderant, plastic, directional force. In the Futurist painting, this current of light is considered a direction of form that can be drawn, exists as a form, and has the tangible value of any other object.”[39]

The numerous electric globes that pepper the uppermost portion of The Laugh certainly correspond with this formal characterization: each projects its own precise, durable, and delineated ray, which strikes rather than suffuses the raucous interior. These beacons, through their divergent angles, augment the off-kilter mood while also directing the viewer’s eye into various points amid the fray, especially the picture’s protagonists: three tawdry prostitutes and their two gentlemen callers. The lights, moreover, expose the scene much as a spotlight would, throwing into sharp relief the fact that the coquettes’ allure is as artificial as their own.[40] This analogy is fitting in that arc lamps exude a luminosity so piercing that they are used today largely as searchlights.[41]

As Christine Poggi has discussed, Severini also investigated the interplay of electric light in modern settings of leisure and entertainment, especially cabarets and dance halls.[42] Severini’s The Pan Pan at the Monico, for instance, envisions a vibrant, cacophonous crowd in a Parisian night club, dining and dancing beneath a flurry of angular lights.[43] The artist clusters the sharp beams at the topmost register of the painting in a similar manner to those in The Laugh, but Severini’s light is truncated and does not plumb the throng below. Severini protracts his light’s scope, however, in The Milliner, another of his eight paintings exhibited at the Bernheim-Jeune. This work appears to have been realized in compliance with such penetrative principles as those espoused in Boccioni’s Futurist Painting and Sculpture and “The Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting”; the former trumpets light’s intersectional propensity, and the latter declares that perceptible forms interpenetrate each other.[44] Accordingly, Severini increases the composition’s sense of movement through the division of both color and form, and employs the lofted, electric orbs as a central fomenter of this dynamism.[45] The artist pictures the milliner’s face in duplicate, perhaps as a tribute to the “Technical Manifesto’s” insistence that “a profile is never motionless before our eyes, but appears and reappears,” and that “moving objects constantly multiply themselves.”[46] The rays of yellow-white light splinter the female form into a miscellany of geometric planes of color.[47] Light as a catalyst for scenic fragmentation is explicitly pronounced in the exhibition catalogue’s accompanying caption: “The electric light divides the scene into defined zones. A study of simultaneous penetration.”[48]

These paintings harness artificial, electric beams as Futurist “force-lines,” or explosive, rhythmic rays that cast an image into flux and fracture, in homage to the disorienting essence of modern life’s sensory impact.[49] Max Kozloff similarly observes: “The Futurists came to think of the picture zone as a flickering network of multiple stresses, charged with electrical currents, invisible forces now controlled by man.”[50] In short, electric light physically conducted a scintillating current, and the Futurists strove to channel that force pictorially within the works comprising their debut; Stella came face to face with these canvases, and likely Boccioni, Severini, and Carlo Carrà (1881–1966), at the Bernheim-Jeune in 1912.[51] It stands to reason that he would have also perused the exhibition catalogue, which included reprints of the “Founding Manifesto of Futurism,” “The Technical Manifesto,” and “The Exhibitors to the Public” statements.[52] Stella came to know Severini personally during his remaining months in Paris,[53] and he owned a copy of Boccioni’s Futurist Painting and Sculpture—he even wrote to the author in 1914 to relay his admiration for it.[54] The influence of the Futurist program over Stella’s work in this period, therefore, cannot be overstated. Most frequently, art historians have noted the formal similarities between Stella’s Battle of Lights and Severini’s The Pan Pan at the Monico, which was also on view in Paris. While this work is certainly a fair precedent, it is important to consider Stella’s additional inflection by other Futurist works from this moment, and more specifically, by the Futurists’ treatment of artificial light in their painting and rhetoric.

Coney Island: Incandescence as Spectacle

Fig. 3. Detroit Publishing Co., The Electric Tower at Night, Luna Park, Coney Island, N.Y., c. 1903. Glass negative, 8 x 10 in.Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division, Washington, D.C.

The vertiginous abundance of electric light found at Coney Island, more than any other attraction, sparked Stella out of his initial creative rut.[55] In his own words, he described the revelation:

For years I had been struggling both in Europe and America without seeming to get anywhere. I had been working along the lines of the old masters, seeking to portray a civilization long since dead. And then one night I went on a bus ride to Coney Island during Mardi Gras. That incident was what started me on the road to success. Arriving at the Island I was instantly struck by the dazzling array of lights. It seemed as if they were in conflict. I was struck with the thought that here was what I had been unconsciously seeking for many years. The electrical display was magnificent.[56]

Although Stella later spoke of his efforts to capture the “hectic mood” of “the surging crowds and the revolving machines,” it is noteworthy that the park’s contentious lights struck the first and most resounding chord in him.[57] The roiling illumination afforded by the “City Electric” held consistent sway in Stella’s artistic vision, as revealed in one of his prose poems about New York: “The searchlights that plow your leaden sky in the evening awaken and stimulate the imagination to the most daring flights, and the multicolored lights of the billboards create a new hymn of praise.”[58] Stella’s paean conjures an image of legions of burning bulbs joining in with Marinetti’s Futurist chorus, expressed in the final declaration from the 1909 Futurist Manifesto: “We will sing of the vibrant nightly fervors of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons.”[59] To be sure, the eponymous feature in Battle of Lights figures prolifically and variably, whether in the pearly globules and vivid pinpricks scattered throughout; the blunt, sharp-edged shafts toward the bottom register; or in the longer, more dramatic spears which dart across the upper portion. When held in comparison, the more condensed, triangular shards recall Severini’s luminous facets in The Pan Pan, and the sweeping searchlight beams seem to gesture toward those that crown The Laugh by Boccioni. Irma B. Jaffe likewise recognizes Stella’s polychromatic light shafts as directional “Futurist ‘lines of force’ ” in their own right.[60]

Within this fluorescent squall, Stella embeds a medley of images that hint at several of Coney Island’s most iconic landmarks.[61] Robin Jaffee Frank, in her exhibition catalogue Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, has painstakingly identified each of these “fragments of reality,” many of which were to be found in Luna Park, or the “Electric Eden,” as it came to be called.[62] Suspended above the maelstrom at center is Luna’s electric steeple, or the “Kaleidoscopic Tower,” which not only blazed with thousands of incandescent bulbs, but also with the overwhelming power of revolving floodlights. The isolated crescents and pinwheels to the lower right of the spire mimic those that ornamented the park’s Surf Avenue entrance, while directly to the left, the spindly black spokes, “festooned with twinkling lights,” evoke the steel skeleton of the Ferris Wheel at Steeplechase, another amusement park nearby. A powder-blue coil to the right of center may approximate Luna’s celebrated Loop-the-Loop ride; several vague elephant-like profiles point to their actual presence at Luna for rides and tricks; and condensed words—such as “FELT” and “PARK”—refer through their particular font treatment to the signs that emblazoned both “Feltman’s,” a popular Coney Island diner, and the entrance to Luna Park. The “whirling vortex” in the lower left portion of the canvas symbolizes the procession of floats that accompanied the Mardi Gras festivities, and the flock of dark, flinty splinters that swarms upward from the bottom denotes the massive crowds lured by this annual, commercial variant of the pre-Lenten holiday.[63] Stella does not exaggerate the gathering’s dense magnitude; the New York Times reported that this eleventh annual carnival “was witnessed by the largest crowd which ever attended the opening night of a Mardi Gras—350,000 persons.”[64]

Spurred by the popular appeal of extravagant electrical demonstrations at world’s fairs and expositions, entertainment venues strategically hastened to include light within their design and attractions.[65] As David Nye has made clear, the expansion of electrification within the United States transpired in tandem with the “first great period of American world’s fairs,” from the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia to the 1915 Panama Pacific Exposition.[66] The four largest fairs—those which took place at Chicago (1894), Buffalo (1901), St. Louis (1904), and San Francisco (1915)—were coordinated by electrical corporations and consequently granted their installations pride of place.[67] The Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo carries particular import for this study. Not only was it intended to commemorate a century of American technological progress, but it was also the meeting place of the eventual creators of Coney Island’s Luna Park, Frederick Thompson and Elmer “Skip” Dundy.[68] These two men, both amusement concession developers and former competitors, collaborated to produce some of the Buffalo Fair’s most successful shows, including the “Darkness and Dawn” cyclorama and “A Trip to the Moon,” a whimsical ride that simulated space travel.[69] Although their lunar landing would later figure among Luna Park’s myriad diversions and even inspire the name, it was the Pan-American’s massive illumination scheme that most deeply colored Thompson and Dundy’s design for their “colossal electric carnival.”[70]

Luther Stieringer, an electrical engineer, with the support of Henry Rustin, the chief of Buffalo’s electrical bureau, endeavored to literally outshine the record-breaking light installation at Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition.[71] To achieve this, he eschewed arc lighting and instead encrusted every available “building, walkway, cornice, and window” with two hundred thousand incandescent globes, thereby introducing “nocturnal architecture.”[72] The incandescent bulb had been perfected by Thomas Edison in 1878 through the implementation of a more durable carbonized bamboo filament, and its luminosity proved steadier than arc lamps and mellow enough for domestic use.[73] In effect, Stieringer enhanced the fair’s architectural contours through “clusters and lines” of Edison’s lights, rather than through uniform arc illumination from below.[74] This approach, called the “luminous sketch,” edited structures into stark “geometric shapes” upon nightfall, and endowed their raw outlines with glaring intensity.[75] The midway’s “Electric Tower” functioned as an especially dramatic example of this method, coruscating with innumerable electric flares and erupting with spotlights at 390 feet (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).[76] The playwright Maxim Gorky described these fiery profiles as they similarly appeared some years later on Coney Island: “A fantastic city all of fire [that] suddenly rises from the ocean into the sky. Thousands of ruddy sparks glimmer in the darkness, limning the fine, sensitive outline on the black background of the sky, shapely towers of miraculous castles, palaces, and temples. . . . Fabulous and beyond conceiving, ineffably beautiful, this fiery scintillation.”[77]

Fig. 4. Charles Dudley Arnold, Electric Tower, c. 1901. Black and white film copy negative. Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division, Washington, D.C.

Fig. 5. View of Luna Park at Night, Coney Island, N. Y., Postcard, 1901-1907. Published by the Illustrated Postcard and Novelty Co., New York. 9 x 14 cm. From the New York Public Library.

Stella’s Electric Palette and the Technological Sublime

As discussed earlier in this essay, the artist interweaves a panoply of “fragments of reality” and prioritizes the “rhythm of the scene” over an exclusively faithful visual representation.[83] Scholars have demonstrated that the many implanted icons illustrate the park’s actual rides, buildings, and signage; with this in mind, it stands to reason that Stella’s interpretation of electric light would have also been obliquely tethered to the physical components of Coney Island’s illumination scheme. A closer look at several of Stella’s studies for the picture will buttress this proposal. In a preliminary oil, Battle of Lights (1913), Stella roughly delineates familiar facets of Coney’s fantastic landscape: the Kaleidoscopic Tower, Ferris wheel, decorative crescent moon, and several multicolored light beams which crisscross at center. Stella, however, manifests the image through predominantly divisionist strokes or an “enlarged pointillism”; John I. H. Baur has gone so far as to suggest that the style of this study most closely resembles “pre-Futurist canvases by Severini, such as his Spring in Montmartre of 1909.”[84] Baur continues with another intriguing proposition: “It seems almost as if Stella had set himself this task of mastering the Italian artist’s earlier style before following him into Futurism.”[85]

If we subscribe to Baur’s line of thinking, we can plausibly trace a Futurist progression in Stella’s preparatory oil sketches, one of which reveals a greater sensitivity to the nuances of artificial light’s appearance.[86] In Luna Park (1913), Stella renders the scene’s irradiance once more in the form of multiple, rounded daubs, but this time, he also conveys it through sharp, solid “force-lines,” a number of which are especially prominent in the lower left quadrant. This subtle shift in mark-making indicates not only an increasingly Futurist aesthetic, but also the basic fact that Stella was registering and emphasizing electric light’s optical versatility to a greater degree. In Luna Park and beyond, electricity set individual bulbs alight, transforming them into concentrated orbs of luminosity, but its illumination extended far past the confines of any glass encasement, namely through the brilliant beams propelled by floodlights. The full repercussions of this more comprehensive appreciation came to the fore in the final picture; lights strobe and dapple, shimmer and probe, just as they did in real life as well as in the Futurist vision.

That being said, Stella’s visualization emphatically omits certain naturalistic effects, which is to say that his wild and diverse luminescence is not light per se, but sheer color. Stella sought to “electrify” his palette, professing that he used “the intact purity of the vermilion to accentuate the carnal frenzy of the new bacchanal and all the acidity of lemon yellow for the dazzling lights storming all around.”[87] It is clear from this quotation that Stella selected particular shades for corresponding moods and sensations, and his use of lemon yellow or pure vermilion served to conjure both the violent intensity and artificiality of Coney’s spectacle. These and many other unadulterated hues vigorously bisect and jostle against each other, but do not commingle, and Stella endows each color-light facet with its own precise outline. As a result, the illusion of depth is diminished, yet not entirely eliminated. The light projections and sundry park structures interlace to such a consistent degree that a sense of monumental three-dimensionality remains, and this union of color and form exemplifies Stella’s “quest” for a “chromatic language that would be the exact eloquence of steely architectures.”[88] To this point, the composition’s voluminous and frenetic tangle may even allude to the way in which electricity physically operated, spreading “weblike” through every locale imaginable, whether private or public, urban or rural, fit for commerce or leisure, plugging each entity into its “network of circuits and currents.”[89]

The viewer, confronted with this mural-scale, riotous tableau, experiences a sensation of smallness that almost equals the diminutive stature of the “human” particles in the bottom register. The awesome proportions of the park’s harlequin fury, looming above the dark horde, accentuate the staggering nature of the park’s visual experience; Stella erects an image indicative of the “technological sublime,” or the “rupture or ordinary perception” experienced by most spectators in the face of such revolutionary, manufactured objects or scenes.[90] Luna Park’s brilliancy overhauled night entirely, and indeed, Battle of Lights projects a shocking and disquieting oasis of artificial daylight, free of any vespertine pall.[91] Stella’s incendiary and centrifugal design, moreover, bespeaks the very action of a dynamo, the machine that precipitated and pumped vast amounts of electricity across great distances—an indispensable device for powering Coney’s gargantuan amusement centers.[92] The composition both tightly coils and releases this energy, and the patchwork of pictorial elements is most compressed in the lower section and at center, while the upper portion of the canvas is less cluttered and thus establishes an impression of skyrocketing movement. The “conflict” of Battle of Lights is not merely internal to the “lights” themselves; Stella’s electric nocturne also optically assails its spectators, a microcosm of the visual conflagration that distinguished Coney Island in the early twentieth century.

Conclusion: “Stupendous Patterns”

In sum, Stella’s formal realization of electric light and its effects supports a notion that has been widely upheld by art historians, but rarely studied in detail: that Battle of Lights reflected “a perfect combination of modernist subject and style.”[93] Likewise, Barbara Haskell lauds Stella’s success in “aligning the subject matter of technological life to a style that encapsulated the dynamism and speed which technology engendered.”[94] The Futurists aimed to yoke mechanistic matter to their visual rhetoric, and although Balla, Boccioni, and Severini accomplished vital steps toward such a formal union, their efforts were necessarily hampered by the fact that the European cultural context possessed neither the scale nor the intricacy of American technology and urban expansion.[95] Wanda Corn has aptly suggested that Balla’s captivation by a single lamp in Streetlight would have been “utterly quaint and precious” to Stella; regardless, it is possible that Stella would never have discovered the power of this theme without the visual aid of Futurist canvases like it.[96] Battle of Lights encapsulated the felt impact or, in a Futurist lexicon, the “dynamic sensation,”[97] of Coney’s thoroughly modern and mesmeric vista, an experience poignantly characterized by E. E. Cummings in an essay on the island: “The thousands upon thousands of faces paralyzed by enchantment to mere eyeful disks, which strugglingly surge through dizzy gates of illusion; the metamorphosis of atmosphere into a stupendous pattern of electric colors, punctuated by the continuous whisking of leaning and cleaving ship-like shapes.”[98]

Endnotes

[1] This print is reproduced in Rem Koolhaas’s canonical urban study, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1994), 35. Unfortunately, Koolhaas did not provide any information as to the identification of the image, and I have been unable to locate it elsewhere in my own research. The depicted structure was originally dubbed “a kind of May-Pole in the water” by William Bishop in his essay “To Coney Island,” Scribner’s Magazine 20, no. 3 (July 1880): 355.

[2] Michael Immerso, Coney Island: The People’s Playground (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 27. Immerso describes Coney Island’s location as “at the southern rim of the Borough of Brooklyn, not quite ten miles from Manhattan,” 12.

[3] Joachim Homann, Night Vision: Nocturnes in American Art, 1860–1960 (Bowdoin, ME: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2015), 21.

[4] Immerso, Coney Island, 27.

[5] Jane Brox, Brilliant: The Evolution of Artificial Light (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2010), 108.

[6] New York Herald, 1882, quoted in Brox, Brilliant, 123.

[7] New York Times, 1880, quoted in Brox, Brilliant, 108.

[8] Wanda M. Corn has drawn this distinction in the various “New York electric nocturnes” executed by American artists such as Joseph Pennell, John Sloan, Birge Harrison, Everett Shinn, Theodore Butler, and George Luks. Corn observes: “The artists of the new New York . . . clearly registered that their lights were modern, electric and standardized. . . . Their light was ‘harder’ than Whistlerian light, and its source in new technologies was well defined.” See Corn, The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999), 171–72.

[9] Peter Conrad, The Art of the City (New York: Oxford Press, 1984), 132. In a corresponding fashion, the Futurists regarded the past as tantamount to “the age of the oil lamp.” See the full quotation in “Variety Theater” (1913) in F. T. Marinetti, Critical Writings, ed. Günter Berghaus, trans. Doug Thompson (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2006), 185.

[10] Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini, “La pittura futurista: Manifesto tecnico” (Milan: Uffici di Poesia, April 11, 1910), trans. in Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 65.

[11] Marinetti, Critical Writings, 28.

[12] Anne d’Harnoncourt, Futurism and the International Avant-Garde (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1980), 16.

[13] Joseph Stella was born the fourth of five sons in the mountain village of Muro Lucano in the southern Apennines on June 13, 1877. When he was eighteen, he joined his oldest brother, Antonio, in New York, and first studied painting under William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) at the New York School of Art. For an in-depth investigation into the implications of Stella’s trans-cultural identity, see Laura Blandino, “ ‘There’s no place like home, but where is home?’ Migrazione, straniamento e appartenenza nell’opera del pittore Joseph Stella,” Scritture Migranti 7 (2013): 157–183.

[14] Corn, Great American Thing, 179. A German visitor to the United States noted that the Americans had “learned how to harness steamships, railways, the telegraph system, and agricultural machines to their uses . . . with a vigor and determination for which we Europeans have not example.” Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904), Sketches of Urban and Cultural Life in North America, trans. and ed. Stewart A. Stehlin (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988), 3–4.

[15] Barbara Haskell also posits the glorification of New York as a “paradigm of modernity” by fellow European expatriate Francis Picabia (1879–1953) as fodder for Stella’s mature work. Following the opening of the Armory Show in 1913, Picabia was quoted in the New York American: “You of New York should be quick to understand me and my fellow painters. Your New York is the cubist, the futurist city. It expresses its architecture, its life, its spirit, in modern thought.” In Francis Picabia, “How New York Looks to Me,” New York American, March 30, 1913, no page number; cited in Barbara Haskell, Joseph Stella (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994), 39–42.

[16] Joseph Stella, “Discovery of America: Autobiographical Notes,” ARTnews 59, no. 7 (November 1960): 41–42.

[17] Immerso, Coney Island, 74.

[18] “Guides are Needed at Cubist Art Show,” New York Times, February 3, 1914, 7.

[19] Richard Cox, “Coney Island, Urban Symbol in American Art,” New York Historical Society Quarterly 60, no. 1/2 (January/April 1976): 41.

[20] I am positioning my argument at the nexus of artistic modernism and broader visual culture upon the exhortation of historian John F. Kasson, who notes that the majority of previous scholarship on Stella has interpreted his work solely by virtue of its contributions to “high modernism.” Kasson rightly nuances such readings: “Stella’s Battle of Lights suggests that a powerful new modern way of seeing was created as much at amusement parks as in artists’ salons, and that artistic modernism was more deeply and complexly related to popular commercial art than we might initially imagine. . . . A work such as Battle of Lights fuses modernist idioms with the battles of modern mass culture that have continued up to the present moment.” See Kasson, “Seeing Coney Island, Seeing Culture: Joseph Stella’s Battle of Lights,” The Yale Journal of Criticism 11, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 101.

[21] Here, I am building upon the following contention posited, but not extensively clarified, by David Nye: “Stella embraced the machine age and the special effects of the lighting engineers, not only making electrical technologies a central theme . . . but adopting its colors and lines as part of his visual vocabulary.” See Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880–1940 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), 80. Other scholars, most notably Robin Jaffee Frank, Irma B. Jaffe, and Barbara Haskell, have more often explicated the components of the Battle of Lights that portray various aspects of Coney’s theme parks. To my knowledge, none have closely scrutinized the specific pictorial impact of electrical illumination.

[22] Ernest Freeberg, The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America (New York: Penguin Press, 2013), 9; Heinz Widauer, “Divisionism in Italy: From Symbolist to Electric Light,” in Ways of Pointillism: Seurat, Signac, and Van Gogh, ed. Widauer, trans. Brigitte Willinger and Gerard A. Goodrow (Vienna: Albertina, 2016), 231.

[23] Widauer, “Divisionism in Italy,” 231.

[24] Brox, Brilliant, 102–103.

[25] Brox, Brilliant, 104.

[26] Freeberg, Age of Edison, 18.

[27] Simonetta Fraquelli, “Modified Divisionism: Futurist Painting in 1910,” in Italian Futurism 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, ed. Vivien Greene (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2014), 80.

[28] Simonetta Fraquelli, Giovanna Ginex, Vivien Greene, and Aurora Scotti Tosini, Radical Light: Italy’s Divisionist Painters 1891–1910 (London: National Gallery, 2008), 13. For the original publication of Ogden Rood’s color theory, see Rood, Modern Chromatics: With Applications to Art and Industry (London: Kegan Paul, Trench and Co., 1879). The discoveries of the French chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889) were also implicated in the Divisionist approach, especially those included in his De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs (Paris: Pitois-Levrault, 1839).

[29] Fraquelli, “Modified Divisionism,” 80. For more information on Divisionism as socially engaged, see Giovanna Ginex, “Divisionism, Neo-Impressionism, Socialism,” in Divisionism and Neo-Impressionism: Arcadia and Anarchy, ed. Vivien Greene (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2007), 28–41. Gaetano Previati (1852–1920) was one of the preeminent pioneers of Divisionism in Italy; he greatly influenced the Futurists with his devotion to the integration of subjective insights and scientific ideas, as detailed in his various manuals on Divisionist theory, such as I principii scientifici del divisionismo: la tecnica della Pittura (Torino: Bocca, 1906).

[30] Boccioni et al., “La pittura futurista: Manifesto tecnico,” 64–67.

[31] In “A Futurist Speech by Marinetti to the Venetians,” Marinetti addresses the city’s inhabitants: “What we want now is that the electric street lamps, with their thousand stabbing points, slice into and violently tear apart your mysterious darkness, which is so bewitching and persuasive!” In Marinetti, Critical Writings, 166.

[32] Fraquelli et al., Radical Light, 131; Brox, 107.

[33] Heinz Widauer employs the word “hooklet” in his essay “Divisionism in Italy,” an apposite descriptor for Balla’s mark-making; see page 232. The carbon substance in arc lamps, when vaporized, can reach a temperature as high as 6500 degrees Fahrenheit. See “The Firm Form of Electric Light: History of the Carbon Arc Lamp (1800–1980s),” Edison Tech Center, accessed April 10, 2017, http://www.edisontechcenter.org/ArcLamps.html.

[34] Sir Humphry Davy first coined the term “arch lamp,” which was later spelled “arc,” in response to the curved orientation of the current. See William Slingo and Arthur Brooker, Electric Engineering for Electric Light Artisans (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1898), 607. See also Thomas B. Cole, “Street Light,” The Journal of the American Medical Association 306, no. 16 (October 26, 2011): 1739.

[35] Cole, “Street Light,” 1739. Cole speculates that Balla, after staring for great lengths of time at the street lights, may have suffered from “arc eye” photokeratitis, “a painful burn of the corneas resulting from unprotected exposure to the ultraviolet rays emitted by electrical arcs.” (It should be mentioned that Cole does not supply any particular citation for this claim.)

[36] Balla certainly intended to exhibit with the Futurists in 1912, but Boccioni, by then “the mouthpiece of the Futurist movement,” ultimately refused his work’s inclusion, claiming that it was not sufficiently Futurist in style. See Widauer, “Divisionism in Italy,” 232.

[37] Here I have in mind the connections drawn by Jeffrey T. Schnapp between the mechanical traits of an airplane propeller and the “argument and form” of Marinetti’s “Technical Manifesto.” See Schnapp, “Propeller Talk,” Modernism/modernity 1, no. 3 (September 1994): 153–178.

[38] I borrow this term “mechanical muses” from Christine Poggi’s Inventing Futurism: The Art and Politics of Artificial Optimism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009), 19. Just as “Futurist painters . . . learned to take dictation from motors,” so too did they look to electricity for creative inspiration.

[39] Umberto Boccioni, Futurist Painting and Sculpture (Plastic Dynamism), trans. Richard Shane Agin and Maria Elena Versari (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust, 2016), 126. Boccioni positions the Impressionist technique as a generative foil for Futurism: “Everything that in Impressionism was a simple fusion of tones, running no risk of being defined as either form or volume, becomes instead, in our pictorial and sculptural production, a resolute determination of planes and volumes that interpenetrate, chase after, and exert an influence on one another in their infinite variety of thickness, transparency, and weight,” 125.

[40] Poggi, Inventing Futurism, 212.

[41] Cole, “Street Light,” 1739.

[42] Poggi, Inventing Futurism, 216.

[43] Severini’s original Pan Pan at the Monico was lost and presumed destroyed. The artist later reproduced the painting from photographs in 1959. See John I. H. Baur, Joseph Stella (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1971), 31. For more on Severini’s thematic interest in dance, see Daniela Fonti, Gino Severini: The Dance, 1909–1916 (Milan: Skira and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 2001).

[44] Boccioni, Futurist Painting and Sculpture, 126; Boccioni et al., “La pittura futurista: Manifesto tecnico,” 64–67. The manifesto proffers, “Our bodies penetrate the sofas upon which we sit, and the sofas penetrate our bodies,” 65.

[45] Anne Coffin Hanson, Severini Futurista: 1912–1917 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 1996), 35.

[46] Boccioni et al., “La pittura futurista: Manifesto tecnico,” 64.

[47] Poggi, Inventing Futurism, 216.

[48] Quoted in Hanson, Severini Futurista, 67. It is important to distinguish that The Milliner and The Haunting Dancer were the only two works by Severini to be illustrated in the Bernheim-Jeune’s exhibition catalogue.

[49] The Futurists defined force-lines in “The Exhibitors to the Public”: “All objects, in accordance with what the painter Boccioni happily terms physical transcendentalism, tend to the infinite by their force-lines, the continuity of which is measured by our own intuition. It is these force-lines that we must draw in order to lead back the work of art to true painting. We interpret nature by rendering these objects upon the canvas as the beginnings or the prolongations of the rhythms impressed upon our sensibility by these very objects.” See Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, and Gino Severini, “The Exhibitors to the Public,” February 1912, in Rainey, Poggi, and Whitman, Futurism, 107.

[50] Max Kozloff, Cubism/Futurism (New York: Charterhouse: 1973), 119. Constance Classen also alludes to Futurism’s integral identification with the “electrical revolution,” and summarizes that, for the Futurists, “this electrification of the world would lead to visual aesthetics and eye-minded rationalism being superseded by a kinesthetic fusion of force, thought, and feeling.” See Classen, The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 185–86.

[51] Stella wrote to Carrà ten years later: “We met at the Bernheim Gallery in Paris, at the first Futurist exhibition—and perhaps you will not remember me, as we have not seen each other again. Through from a distance, here in New York (where I have lived for years) I have always followed with interest and strong liking your lively work of an artist innovator, and I have always hoped, for the love that I bear my country of origin, for a show in New York of the bold and recent conquests accomplished by you and your companions to the glory of Italy.” Cited in Baur, Joseph Stella, 30–31.

[52] Haskell, Joseph Stella, 38.

[53] Stella would have become familiar with Severini through close mutual friends, among them the Italian, Paris-based painter Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) and the American artist and critic Walter Pach (1883–1958). See Haskell, Joseph Stella, 38.

[54] Lisa Panzera, “Italian Futurism and Avant-Garde Painting in the United States,” in International Futurism in Arts and Literature, ed. Günter Berghaus (Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2000), 231.

[55] The 1913 Armory Show also catalyzed Stella’s trajectory toward modernism. By Barbara Haskell’s estimation, it was “less the art than the rhetoric employed to explain it” that encouraged him; the press repeatedly heralded the exhibition’s modernist works as “futurist art,” even though no official Futurist artists had participated. See Haskell, Joseph Stella, 38. Stella himself refers to the exhibition’s motivational influence: “Soon after the show I got very busy in painting my very first American subject: Battle of Lights, Mardi Gras, Coney Island.” See “Discovery of America,” 6.

[56] He concludes: “On the spot was born the idea for my first truly great picture.” Joseph Stella, “I Knew Him When,” Daily Mirror, July 8, 1924.

[57] Stella commented on the elements of the amusement park as they relate to Battle of Lights in more detail: “I felt that I should paint this subject upon a big wall, but I had to be satisfied with the hugest canvas that I could find. Making an appeal to my most ambitious aims. . . . I built the most intense dynamic arabesque that I could imagine in order to convey in a hectic mood the surging crowd and the revolving machines generating for the first time, not anguish and pain, but violent dangerous pleasures.” See “Discovery of America,” 6.

[58] The poem is undated; for the full version in English, see Haskell, Joseph Stella, 219. The original Italian text is published in Irma B. Jaffe, Joseph Stella (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970), 146. I am appropriating Barbara Haskell’s term “City Electric” here to refer to New York. See Haskell, Joseph Stella, 171.

[59] F. T. Marinetti, “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism,” in Marinetti: Selected Writings, ed. R. W. Flint, trans. R. W. Flint and Arthur A. Coppotelli (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1971), 41; originally published in Le Figaro (Paris), February 20, 1909.

[60] Jaffe, Joseph Stella, 40.

[61] Stella even exercised the synthetic Futurist working method put forth by Balla, Boccioni, Carrà, Russolo, and Severini in “The Exhibitors to the Public”: “In order to make the spectator live in the center of the picture, as we express it in our manifesto, the picture must be the synthesis of what one remembers and of what one sees,” 106. Stella’s friend Carlo de Fornaro recalled the following parallels in the artist’s approach: “Several weeks were dedicated to myriads of observations. . . in a manner of an artistic detective in a hunt for the solution of a pictorial mystery. He had to visualize the picture on a flat and square canvas. . . . Several nights were dedicated to meditation upon the execution in oils of his clear drama. . . . While discussing this artistic parturition, Stella remarked that after weeks of studies and cogitations the full-blown idea had flashed into his mind like an inspiration.” See Carlo de Fornaro, “Joseph Stella: Outline of the Life, Work, and Times of a Great Master,” unpublished manuscript (New York: 1939), 30–31, quoted in Jaffe, Joseph Stella, 40.

[62] Robin Jaffee Frank, Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland 1861–2008 (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, in association with Yale University Press, 2015), 40–43. Frank describes how she crowdsourced the identification of many of the attractions in her article “Coney Island Baby,” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (2015): 120–121. Contemporary reviewers made mention of the painting’s piecemeal attitude: “Here is a fragment of an audience watching a fragment of dancers. Fragments of steel construction are seen, fragments of architecture, a word or two from a sign, all packed in a confusion of lights,” The Christian Science Monitor, February 1914, 10.

[63] These identifications between the actual Coney Island amusement parks and Stella’s composition are based on those enumerated first by Robin Jaffee Frank; for a more exhaustive list, see her volume Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 40–43. John F. Kasson explains that the yearly Mardi Gras staged by Coney Island “was not a pre-Lenten holiday but a special post-Labor Day celebration that had been instituted, improbably enough, as a fund-raising effort for the Coney Island Rescue Mission for wayward girls.” See Kasson, “Seeing Coney Island: Seeing Culture,” 95–96.

[64] “Coney Mardi Gras Draws Huge Crowd,” New York Times, September 9, 1913, 7.

[65] Freeberg, Age of Edison, 116.

[66] Nye, Electrifying America, 33.

[67] Nye, Electrifying America, 33.

[68] Immerso, Coney Island, 60–61.

[69] Immerso, Coney Island, 60-61. For a full description of the ride “A Trip to the Moon,” see John F. Kasson, Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978), 61.

[70] Immerso, Coney Island, 62.

[71] Nye, Electrifying America, 42–43. See also Judith A. Adams, The American Amusement Park Industry: A History of Technology and Thrills (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991), 38.

[72] Sasha Archibald, “Harnessing Niagara Falls,” Cabinet, no. 19 (Fall 2005): no page number.

[73] Brian Bowers, Lengthening the Day: A History of Lighting Technology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 69. Edison Electric Light Company promoted the incandescent lamp as infinitely preferable to the arc, and it would indeed eventually replace the former mode: “In the incandescent electric lamp we have a source of light free from the faults and possessing advantages foreign to either the arc light or gas. With these lamps, light may be distributed more uniformly; they can be furnished of a brilliancy ranging from sixteen to two hundred and fifty candles, or, by grouping, may be made to equal or even to excel the arc.” See Edison Electric Light Co., The Edison Incandescent Electric Light: Its Superiority to All Other Illuminants (Montreal: 1888), 9. Electric lighting became a standard domestic amenity by the late 1920s; for more information, see Mark H. Rose, Cities of Light and Heat: Domesticating Gas and Electricity in Urban America (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995).

[74] Nye, Electrifying America, 44.

[75] Archibald, “Harnessing Niagara Falls,” no page number. Louis Bell discusses the “luminous sketch” and Stieringer’s mastery of it at length; see Bell, The Art of Illumination (New York: McGraw Publishing, 1902), 283–89. Bell defines the technique: “The configuration of the lights to be used in the luminous sketch that seems needful for the best artistic results may be roughly determined by making by daylight, or better, near sunset, a rough, clear, line drawing of the scene to be illuminated from a rather distant viewpoint, the further as the scale of the work increases. Then the distribution of lights following the principal points and outlines of this drawing will give the main effects that one wishes to produce,” 283–84.

[76] Bell, Art of Illumination, 285–86.

[77] Maxim Gorky, “Boredom,” The Independent 63 (August 8, 1907): 309.

[78] Adams, The American Amusement Park Industry, 47–48. Luna Park took the place of Paul Boynton’s Sea Lion Park, which had been established in 1895. By Lauren Rabinovitz’s count, there were two thousand amusement parks nationwide by 1912. See Rabinovitz, Electric Dreamland: Amusement Parks, Movies, and American Modernity (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 4.

[79] “The Development of Summer Lighting,” Electrical Age, April 1, 1904.

[80] Immerso, Coney Island, 65.

[81] Kristen Whissel, Picturing American Modernity: Traffic, Technology, and the Silent Cinema (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 42. Whissel expands on this point: “As an invisible force sensible only through touch, electricity was known and experienced at the end of the nineteenth century primarily through its effects—light, heat, and motive force—and hence by whatever (signifying) machine completed its circuit,” 118. For more on the evolution and cultural ramifications of light’s increasing “disembodiment” through electricity, see Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

[82] Frank, Visions of an American Dreamland, 40.

[83] Frank, Visions of an American Dreamland, 40. Century Magazine investigated Stella’s expressive mode: “He has evolved a style of his own from various elements in the modern movement. Had he merely represented the physical appearance of the American fiesta, he believed that he could not have given the rhythm of the scene, which transforms the chaos of the night, the lights, and the strange buildings, and the surging crowds into the order, the design, and the color of art.” See “ ‘Battle of Lights, Coney Island,’ from the Painting by Joseph Stella,” Century Magazine 87 (April 1914): 853.

[84] Baur, Joseph Stella, 31. Barbara Haskell makes the same connection; see Haskell, Joseph Stella, 43.

[85] Baur, Joseph Stella, 31.

[86] For information on two other Coney Island studies by Stella, both of which reside in the Hirshhorn Museum’s collection, see Judith Zilczer, Joseph Stella: The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Collection (Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, 1983), 24–27.

[87] Stella, “Autobiographical Notes,” 41. Peter Conrad draws the conclusion that Stella wanted “his colors to glare as blindingly as the lights to which they paid homage.” See Conrad, The Art of the City, 35. For more on Stella’s chromatic strategies, see Joann Moser, Visual Poetry: The Drawings of Joseph Stella (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990), 89.

[88] Quoted in Moser, Visual Poetry, 89.

[89] Whissel, Picturing American Modernity, 3–4.

[90] Whissel, Picturing American Modernity, 129.

[91] Electricity single-handedly paved the way for twenty-four-hour entertainment and production. See William J. Phalen, Coney Island: 150 Years of Rides, Fires, Floods, the Rich, the Poor, and Finally Robert Moses (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2016), 88.

[92] Nadja Maril, American Lighting: 1840–1940 (Westchester, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 1989), 74.

[93] Margaret Reeves Burke, “Futurism in America, 1910–1917” (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 1986), 109.

[94] Haskell, Joseph Stella, 44.

[95] Burke, “Futurism in America,” 2.

[96] Corn, Great American Thing, 179–80.

[97] Balla et al., “The Exhibitors to the Public,” 107.

[98] E. E. Cummings, “Coney Island: A Slightly Exuberant Appreciation of New York’s Famous Pleasure Park,” reproduced in Coney Island Reader: Through the Dizzy Gates of Illusion, ed. Louis J. Parascandola and John Parascandola (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 191–93. This essay was originally published in Vanity Fair in June 1926.

Author Bio:

Ramey Mize is a doctoral student in Art History at the University of Pennsylvania. From Atlanta, Georgia, she holds a BA in Art History from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and her MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. The majority of her research and publications to date examine the intersection of nineteenth-century visual culture, war, and landscape across Europe and the Americas. Her scholarship has been supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Previously, she has served as the Anne Lunder Leland Curatorial Fellow at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, a Summer Fellow at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Center for American Art, and a Curatorial Assistant at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Most recently, Mize co-curated the exhibitions “The World is Following Its People”: Indigenous Art and Arctic Ecology at the University of Delaware’s Old College Gallery and Soy Cuba / I am Cuba: The Contemporary Landscapes of Roger Toledo at the Arthur Ross Gallery, University of Pennsylvania; in June 2019, her exhibition Etch and Flow: Waterscapes by American Painter-Etchers, will open at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Since 2016, she has served as a managing curator of the Incubation Series, a student-run curatorial collective at UPenn. She may be contacted at rmize at upenn.edu.