Phoebe Herland

The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Abstract

A painting by Jackson Pollock hangs next to a painting by Jean Dubuffet at the Tate Modern in London, set apart on a wall of their own. Both titans in their own right, Pollock is of course known as the progenitor of American action painting, and Dubuffet the French father of Art Brut. Geographically and methodologically they are distinct, but they are very often related in British thought. This contemporary hanging at the Tate is but one domino in a chain of comparisons made between Pollock and Dubuffet, which I trace back to post-war London. The first time these artists were seen in tandem was at an exhibition in 1953,“Parallel of Life and Art,” at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in London. It was organized in large part by photographer by Nigel Henderson.

A member of the Independent Group, a renegade group of artists in London’s post-war scene founded at the ICA, Nigel Henderson was the lone photographer among painters, sculptors, and architects. He had unique points of contact with both Dubuffet and Pollock, ultimately leading to their inclusion in “Parallel of Art and Life.” This paper triangulates the relationship between Henderson, Dubuffet, and Pollock. From London, France, and America, why were these artists compatible? How did they come to know one another? Why did Dubuffet and Pollock come to conceptually underpin the Independent Group, mentioned in their various projects so often and particularly as a packaged deal? For answers, I look to letters between Henderson and Dubuffet, largely unknown in the field of Dubuffet scholarship, and track the critical reception of Pollock in early British publications.

London lagged in its post-war recovery, artists noting a “stagnancy” in the very air. I argue that Pollock and Dubuffet, both of whom prioritize physical movement in their practice and in their personal mythology, were taken up by these artists as reprieve from dreary London. They were used by these artists to promote forward motion.

![]()

Action Photography Brut:

Nigel Henderson, Jean Dubuffet, Jackson Pollock, and the Streets of Postwar London

In 1956, Alison and Peter Smithson published an article in Ark, a magazine of the Royal College of Art in London, titled “But Today We Collect Ads.” In rhythmic, repetitive prose, the architects survey sources of artistic inspiration from years past, always returning to the refrain “but today we collect ads.” They contend that “glossies” and “throw-away objects,” the “piece of paper blowing about the street,” are now “the equivalent of the Dutch fruit and flower arrangement.”[1] The Royal College of Art, it should be noted, is one of Britain’s most distinguished art schools. At the time, its program required students to engage with the classics and practice traditional life painting. “But Today We Collect Ads” radically threatened its institutional power. Taste-making, argued the Smithsons, has been transferred to the hands of the ad men, and no longer resides safely with fine art’s “ruling class.”[2]

In the neoclassical building of another of London’s most esteemed art schools, the Courtauld Institute, architectural historian Reyner Banham led a cameraman through the halls in a documentary called “The Fathers of Pop” (1979). Banham, closely associated with the Smithsons, was part of the Independent Group, a postwar cohort of artists whose members hailed from some of the most prestigious art institutions in London. Classical music accompanies Banham’s recollections of student life at the Courtauld, his alma mater, in the early 1950s: as he explains, “We studied Cézanne, Michelangelo, Turner, the whole grand tradition of European art and civilization.” Banham makes his way to a balcony and peers over its wrought iron railing at a Chrysler car on the street below; the music cuts to jazz. In his student days, he recalls, the occasional sight of an American automobile from the library windows was a “vision from another culture.”[3] Pastel paint and reflective chrome in motion, these cars must have provided startlingly bright relief from the grey dreariness of postwar London. They seemed to represent the future, “as alien as spaceships.”[4] The American car became of central interest to the Independent Group; the motif perhaps reached its apex with Richard Hamilton’s 1957 oil painting Hommage à Chrysler Corp, which cemented the American car within the lineage of European painting.

The Independent Group formed at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in the early 1950s. Members have differing recollections about what the group stood for, but it was clear what it stood against: the ICA chairman, Herbert Read, and more generally, stagnant tradition.[5] The group’s name, according to Hamilton, stemmed from a matricidal impulse to stand independently from the ICA, which parented them.[6] At the group’s first “real” meeting in 1952, Eduardo Paolozzi presented a cavalcade of images from his vast personal collection of magazine advertisements and newspaper clippings.[7] This was a generative creative practice that would become fundamental to the group: But today we collect ads. Paolozzi, Hamilton, the photographer Nigel Henderson, and others incorporated these ads into a profusion of collages. It was a radical leap toward Pop Art that went largely unnoticed at the time. Today, as Banham’s documentary acknowledges, these artists are heralded as the “Fathers of Pop.”

For the postwar British artist, the loose, discarded advertisement “blowing about the street” and the flashy American car darting past the Courtauld Institute had a great deal in common. One is trash, the other is garish, and both are set in motion. We might say the same of Jean Dubuffet, with his interest in crude material, and Jackson Pollock, considered garish by virtue of being American—both of whom came to buttress the Independent Group conceptually, much as ads and cars did. References to the two artists, often in tandem, appear throughout writings by thinkers including Henderson, Banham, and the Smithsons.[8] And while Dubuffet’s and Pollock’s frenzied and raw paint handling have been compared by critics outside Great Britain, the pairing met with special fervor in London.[9] One a titan of Europe, the other a titan of America, Dubuffet and Pollock enabled Great Britain to triangulate its new postwar image. Comparing the two reveals similar methodologies based in movement: Pollock stalking his floor-laid canvas, engaging his full body in motion as he paints, and Dubuffet traveling the world in search of Art Brut materials, collecting them as the Independent Group collected ads.

Figure 1. Installation view, Parallel of Life and Art, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, September 11–October 18, 1953. https://library.artstor.org/asset/NYU_DIB__959_1372450.

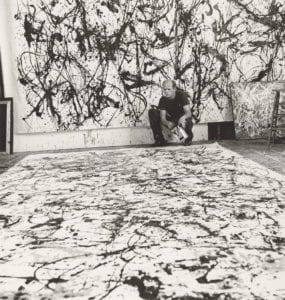

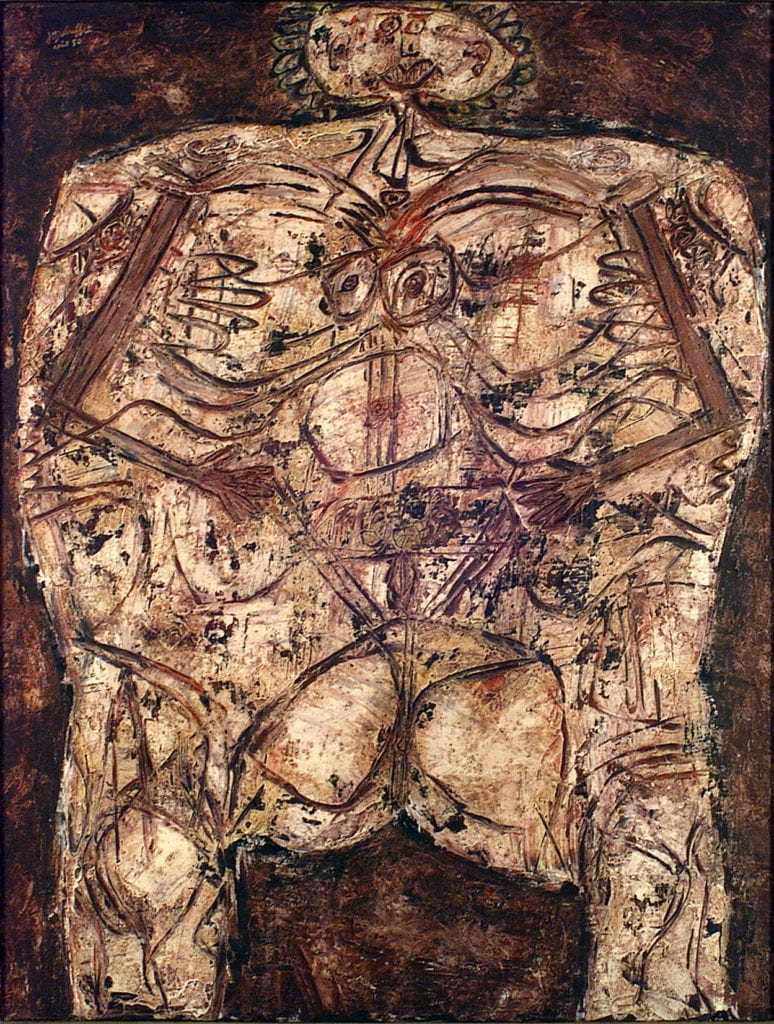

A 1953 show at the ICA, Parallel of Life and Art (Fig. 1), placed Dubuffet and Pollock together in London for the first time—not physically, but through photographic representation. Organized by Nigel Henderson, Eduardo Paolozzi, the Smithsons, and an engineer by the name of Ronald Jenkins, the show contained 122 photographs. Their source material was diverse: an Etruscan funerary vase, Japanese writing, a news clipping of a bicycle race in the midst of a crash, and so on. One photograph, originally taken by Hans Namuth, showed Pollock in his studio (Fig. 2). Another represented Dubuffet’s painting Corps de dame paysagé sanguine et grenat (Fig. 3). Henderson and Paolozzi made the selections, while the Smithsons and Jenkins designed the hanging.[10] Henderson, in large part, photographed the source material. Using a photographic enlarger, he dramatically distorted scale during the printing process. Under his lens, the micro often became macro and vice-versa; a magnified biological cell, it turns out, can be nearly indistinguishable from an aerial view of a mountain range. The show delighted in these comparisons, and actively invited them through its creative use of space. Photographs of diverse sizes were arranged at all heights and varying angles, effectively enveloping the viewer in a three-dimensional collage. As a visitor moved through the space, he or she would set a chain of dominoes in motion, each photograph seeming to resonate differently with those around it.

Figure 2. Hans Namuth, Jackson Pollock in His Studio, c. 1950.

Note: This may not be the exact photograph included in Parallel of Art and Life, but installation shots show, from a distance, a Namuth image from this series with a similar composition.

Although the exhibition was a concerted group effort, its joining of biology and fine art can be traced back to Henderson in particular.[11] So, too, can the inclusion of Pollock and Dubuffet, with whom the artist had special points of contact. By tracing these relationships, we will come to find that the photographic work of Henderson constellates easily between the action painting of Pollock and the Art Brut of Dubuffet. Indeed, photography as a medium, though materially and methodologically distinct from the painterly practices of Pollock and Dubuffet, finds kinship with them through a shared interest in motion.

Figure 3. Jean Dubuffet, Corps de dame paysagé sanguine et grenat, August 1950, oil on canvas, 54 5/16 x 34 1/2 in. (138 x 87 cm). Private collection. © Fondation Dubuffet, Paris/ARS, New York, 2019

Henderson’s mother Wynn, with whom he lived in London’s Bloomsbury district from the age of sixteen, was an art-world socialite. Bloomsbury, in those days, played host to a close-knit group of iconoclasts including Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry, and John Maynard Keynes. From a young age, then, Henderson had access to a deep network of artists and intellectuals with whom he was comfortable engaging with as an equal. Wynn was a close personal friend of Peggy Guggenheim, and served as secretary during the years in which the collector ran the Guggenheim Jeune Gallery (Wynn had even come up with the gallery’s name, a play on the famous Bernheim-Jeune in Paris).[12] Henderson would often help hang shows at the gallery, and his mother managed to slip a few of her son’s works into an Exhibition of Collages, Papiers-collés, and Photo-montages.[13] This gesture either went unnoticed or was welcomed by Guggenheim, whom Henderson came to regard as “kind of a fairy godmother.”[14] We can imagine the psychological empowerment her friendship would offer a young artist such as Henderson, allowing him not only intimate access to major works of art, but also access to the artists themselves. He struck up a friendship with Marcel Duchamp, for example, after the two hung a show together in Guggenheim’s gallery. From this meeting with Duchamp, Henderson gained what he described as a “first-person singular feeling.”[15]

Henderson’s connections would become a boon to artists in the Independent Group who descended from humbler corners of Great Britain. Paolozzi, for example, was an Italian man in a still staunchly racist and classist London. Henderson happily introduced him to Guggenheim and others. The relationship was, it should be noted, mutually beneficial. Like many children of privilege in a self-consciously capitalist world, Henderson idealized the lives and perspectives of those marooned on lower rungs, a theme that recurs in his photographs of London’s East End.

Before his years with the Independent Group, Henderson attended the Slade, a well-established art school in London in step with the Royal College of Art. He studied drawing and painting, “for which he had little aptitude.”[16] As in Bloomsbury, the network in which he embedded himself was crucial: artists he met through the Slade, such as Paolozzi and Hamilton, greatly influenced his work. When Henderson eventually found photography, it was by way of a pivotal gift from Paolozzi—a photographic enlarger—in 1949. He used the same photographic enlarger for Parallel of Life and Art, and it became fundamental to his practice.

The enlarger enabled Henderson to take a unique approach to photography, playing freely with scale and composition, and making photography almost as plastic as paint. His radical approach to photography caught the attention of one of his idols, Dubuffet. Henderson and Dubuffet most likely met in person before 1950, though the exact nature of this meeting is unclear.[17] In 1954, they came in contact again, when Dubuffet encountered a number of what Henderson would call his “stressed” photographs at a photography show at the ICA. Dubuffet purchased six for his personal collection and followed up with a letter of thanks, encouraging Henderson to continue work in this vein.[18]

What was it about these photographs that so appealed to the creator of Art Brut? Their crude materiality and process were, no doubt, central factors. A key feature of Art Brut is that artists gather their materials, subject, and style, “from their own depths, and not from the conventions of classical or fashionable art.”[19] In this sense, the fact that the Slade disparaged photography and discouraged its pursuit, regarding it as “the Devil’s Domain,”[20] qualifies the medium as an Art Brut material. Although Paolozzi and the Independent Group employed advertisements and photography in their work, Henderson alone produced photographic work.[21] He thus was not influenced by a cohort of photographic fellows but was entirely self-directed. Of course, Henderson’s work did not entirely fit Dubuffet’s criteria for anti-cultural art. Henderson was, after all, part of the Independent group. He organized Parallel of Life and Art with his collaborators Paolozzi, the Smithsons, and Jenkins. Even from a young age he was a part of London’s art scene by way of his mother. One could further argue that photography itself, with its chemical and mechanical specificity, requires trained, insider knowledge. Still, Henderson, with his unusual and ad-hoc approach to photography, brings the medium close to what we might call “Photography Brut.”

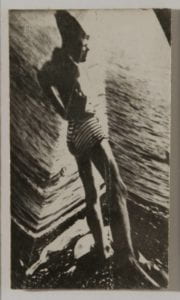

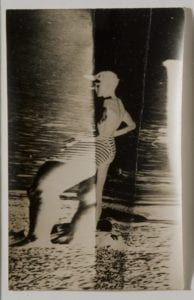

Figure 4. Nigel Henderson, “stressed” images of bathers, c. 1950. Maximum dimensions 5 ½ x 3 ½ in. (14 x 8.9 cm).

Although it is unclear exactly which six prints Dubuffet purchased from the ICA show, at least one, and likely several, were from a series of bathers that Henderson made from a found Victorian lantern slide (Fig. 4).[22] This was an uncharacteristically small-format series for Henderson, the images no larger than five and a half by three and a half inches, like postcards or personal snapshots. The lantern slide pictured boys bathing on a rocky beach near water’s edge, which Henderson printed with variously cropped compositions and aesthetic manipulations. One figure who appears repeatedly is a young boy in striped bathing trunks. He stands with his hands on his hips and looks outward, surveying the beach. Henderson reproduces the boy again and again in several small prints, but each time he appears differently, as if his reflection has been cast in a new funhouse mirror. In one image his body stretches across the entirety of the picture’s frame, his right foot dragged into the bottom right corner. In another, his image is flipped and printed in negative. His body recedes farther into the beach, and his left leg is pulled into elephantine proportion. Importantly, viewers are never given the source image in full; they receive numerous conflicting and incomplete accounts that create a sense of disorientation. There is no stable, “true” image in which to find one’s bearings.

Figure 4. Nigel Henderson, “stressed” images of bathers, c. 1950. Maximum dimensions 5 ½ x 3 ½ in. (14 x 8.9 cm).

Henderson refers to works such as these, in which he makes naïve, tactile interventions, as “stressed images.” To this end, he refers to his photographic enlarger as his “crude drawing instrument,” a phrase that not only evokes the unrefined process of Art Brut, but also relates the impersonal and mechanical photographic medium with the intimate and mutable quality of drawing.[23] To create points of stress in the photographs—the disproportionate pushes and pulls in the picture plane—Henderson bends and folds the printing paper during the printing process, while also enlarging certain points within the composition.[24] After printing, he flattens the paper again, and the image slips and slides in areas in which the negative was exposed at an angle. Cresting waves in the ocean, for example, become attenuated lines of light, pulled like taffy. A bather’s body drags like one of Salvador Dalí’s clocks. The residual creases in the paper become creeping cracks in the composition, alienating the bathers from each other, or worse, from their own limbs. These are ominous photographs, not altogether typical of Henderson’s oeuvre, which also includes street photography of children at play and cheerful collages of bright advertising images. Our expectations for small snapshots of a trip to the beach—expectations perhaps created by the aforementioned advertising images—are upended in this series. This is especially true for those iterations printed in negative, which read like topsy-turvy nightmares. The horizon line, if discernable, is often tilted; it is as if the fixed photographic image has detached from its source and spun like a top.

Here we come to a second, more subtle affinity between Dubuffet and Henderson: both value movement in their work. Dubuffet’s writings, for instance, frequently equate intellectualism with stagnancy and artistry with motion. “The intellectual functions all too often sitting down,” he writes, “in school, at meetings, during conferences—always seated . . . We might even say that school chairs wear down [one’s] clairvoyance along one’s rump.”[25] For Dubuffet, the body and one’s clairvoyance, or creative ability, are deeply connected. If the body is idle then so is the mind. That the artist locates these seated intellectuals in schools, meetings, and conferences is significant, too—they are cloistered indoors, apart from the outside world. To those British artists rebelling against the Slade, the Royal College of Art, the ICA, and so on, this would have been a particularly appealing sentiment. By contrast, in an essay from 1945, Dubuffet writes, “An artwork is all the more enthralling the more of an adventure it has been, particularly if it bears the mark of this adventure . . . If [the artist] himself did not know where it would all lead.”[26] The artist’s adventure is one that travels from one point to another, that leads somewhere. Further, as Dubuffet puts it, “the artist teams up with chance. It takes two to tango, not one; chance always joins in. It pulls to the right, to the left, while the artist leads as best he can.”[27] Here, the artist is a ballroom dancer, the opposite of a seated intellectual. That the artist’s dancing partner is chance should, of course, immediately call to mind Pollock.

The photograph of Pollock selected for Parallel of Life and Art shows the artist in his studio, a painting laid on the floor in front of him. He crouches over it as if stalking prey. The painting takes up the entire bottom half of the composition, distancing Pollock from the photographic frame as he crouches over its far end. A second painting appears on the wall behind Pollock. Both are white with black drip marks, or at least appear that way in the black and white photograph; Pollock, dressed in black, seems to become one of those drip marks. Of the fine art entries in Parallel of Life and Art, including that of Dubuffet’s Corps de dame paysagé sanguine et grenat, Pollock’s is the only studio image. The artist’s right hand is blurred, proving its motion; the artist is valued more for his action than for his product.

Knowledge of Pollock in Great Britain would have been limited at the time his photograph was featured in Parallel of Life and Art in 1953. Henderson’s friendship with Guggenheim, Pollock’s great patron, would have given him special insight into the artist. The first time Pollock’s work was shown in Europe was, indeed, by Guggenheim in 1948 at the Greek Pavilion of the Venice Biennale. Pollock painted the works included there, Eyes in the Heat and Circumcision (both 1946), using a brush. His first drip paintings entered Europe two years later, in 1950, at the American Pavilion of the Venice Biennale. On view were three works: Number A1 (1948), Number 12 (1949), and Number 23 (1949). The pavilion was largely ignored, with the exception of those works by Pollock: a detailed description of how he worked with paint was “assiduously translated,” and inspired virulent reactions both for and against his art.[28] An English critic, David Sylvester, was firmly against. In an article in The Nation, he wrote that the pavilion’s presentation represented “the seamier side of America—sentimentalism, hysteria, and an undirected and undisciplined exuberance.”[29] Regardless of his negative judgment, Sylvester’s recognition of exuberance in the work of Pollock was not entirely incorrect.

As we recall, Banham referred to American cars as “visions from another culture,” emphasizing the otherness of America in Great Britain, a separation with which we can scarcely identify today. The comingling of American and British culture, now deeply rooted, was a trend just beginning at the time. Proponents of “Americanization,” typically young, felt that “the very air of America seems more highly charged, more oxygenated, than the atmosphere in England.”[30] The war had lasting effects; shortages and rationing, for example, persisted until 1954.[31] America had not faced the same consequences, a fact of which the British were acutely aware, and in many cases resented.[32] As much as youth culture embraced Americanization, those who had weathered the war were far more skeptical. “Action Painting” was considered yet another American import, alongside hula-hoops and “barbecued chickens rotating on their spits.”[33] The allure of Pollock and American cars to the Independent Group must have owed, in part, to the artists’ rebellious leanings. British high culture considered American design to be of bad taste, a denigration that the recalcitrant Independent Group wanted to claim for itself.

Beyond Sylvester’s review of the 1950 Venice Biennale, not much appeared in print for British readers regarding the work of Pollock. The only other notable example was an article by Clement Greenberg printed in Horizon Magazine in 1947.[34] In it Greenberg sings Pollock’s praises and firmly situates him as a distinctly American painter—specifically, an American city-dweller: “Pollock’s art is still an attempt to cope with urban life; it dwells entirely in the lonely jungle of immediate sensations, impulses and notions.”[35] Greenberg places Pollock in a “jungle” of sensations and reduces him to his reflexes. Judging by the image Henderson and the others selected for Parallel of Life and Art, which again, shows Pollock crouching over his painting as if a hunter in a jungle of black painterly vines, Greenberg’s characterization seems to have resonated with these British artists.

Beyond these examples, and owing to the anti-American sentiment in Great Britain, knowledge of Pollock in the early 1950s would have traveled primarily by word of mouth.[36] He was thus perceived within a framework similar to Dubuffet’s and the Independent Group’s distrust of academia and celebration of the streets and the common people who circulated in them—Pollock, perhaps, among them. This is a prominent theme in Dubuffet’s writings, which refer to the “language spoken in the street,”[37] and describe vocational house painting more favorably than fine arts. For Henderson, a similar attitude appears in his body of street photographs taken in London’s impoverished East End.

Henderson and his wife Judith lived in Bethnal Green, in the East End, between 1949 and 1953. They resided there so that Judith might work on a sociological project, called “Discover Your Neighbor.” The project followed in the tradition of Mass Observation, a social research effort begun in 1937 to address one central complaint: “how little we know of our next-door neighbor and his habits.”[38] Mass Observation’s leaders proposed a plan to redress this ignorance by compiling extremely detailed information, in the form of photographs and diaries, on the daily lives of “ordinary people,” collected and reported by other “ordinary individuals.”[39] The project was essentially a public and mundane form of espionage: neighbors informed on neighbors, a slightly invasive prospect that was practiced without stigma. Judith Henderson, for her part, kept detailed records on the comings and goings of her and her husband’s neighbors, the Samuels.

Perhaps inspired by the activities of his wife, Henderson began taking brisk walks around this foreign, working-class neighborhood with his Rolleicord camera, a handheld, amateur device that became another crude instrument in his arsenal. The resulting images are often unfocused, as Henderson did not know how to use the camera properly.[40] They are also often blurred; he took them while in motion, or while his subjects were moving. Neither of these facts particularly troubled Henderson. His interests in this project lay not in aesthetics, but in naturalistic observation and “reportage.”[41] Henderson imagined himself as an explorer, or hunter, capturing the daily lives of poor and working-class Londoners. As Robin Kelsey argues in his book, Photography and the Art of Chance, there is a longstanding “structural proximity” between photography and hunting, strengthened by the emergence of hand-held cameras,[42] such as Henderson’s Rolleicord. The term “snapshot,” it is worth noting, derives from hunting.[43] Both the hunter and the photographer rely on their reflexes. As Henri Cartier-Bresson wrote in The Decisive Moment in 1952, the photographer composes a picture “at the speed of a reflex in action.”[44] Speed and reflex both recall the American car and the work of Pollock. For his own contribution to this seemingly pervasive theme in postwar Europe, Dubuffet engages hunting as a metaphor in his writing as well. He describes “random accidents that the artist hunts for, a prey that he constantly calls to and watches for and traps.”[45]

Henderson hunts for “random accidents” in his East End pictures. Chance encounters among billboards, advertisements, and graffiti are loaded with layered meaning. In a photograph he took of a young boy before a boarded up pub in Stepney, c.1949-53 (Fig. 5), for example, the word “STOUT” in the signboard at the top right becomes a double entendre, describing not only the pub’s selection of spirits, but also the pudgy boy standing in the bottom left.[46] The street signs and symbols that Henderson caught in moments of poetic confluence with his camera were restaged for the gallery in Parallel of Life and Art. What the photographs and the exhibition share in common is a willingness to see affinities between objects and things, between Pollock’s drips and splatters. As Dubuffet writes, “there are many objects throughout the world that resemble and evoke one another. We ought to emphasize not the differences and peculiarities but the resemblances.”[47]

Figure 5. Nigel Henderson, Photograph showing an unidentified child standing in front of a closed shop, c. 1949-56.

The Smithsons occasionally accompanied Henderson on his walks through the East End, experiences that led Alison Smithson to refer to Henderson as “the original image finder.”[48] The photograph, under this rubric, becomes an objet trouvé. As Henderson wrote in a letter, “for me the found fragment, the objet trouvé, works like a talisman . . . [it] intercept[s] your passage and wink[s] ‘its’ message specifically at & for you.”[49] His wording reveals an underlying intuition about the magic of motion. Objects, or talismans, intercept people as they pass, implying that both parties are in motion. The phrase is more or less a reworking of Pablo Picasso’s famous adage, “inspiration exists, but it has to find you working,” only in this case the word “working” can be replaced with “moving.”

Robyn Denny, a British artist who studied at the Royal College of Art in the 1950s, recalled the atmosphere of London’s art scene as follows: “Europe was exhausted and wound down. Life in London was grey and austere, its art world more than ever prone to compromise and introspection. I felt the whole culture was flawed and frozen into fixed attitudes of expression and our art to have become shallow and self-indulgent.”[50] Denny’s use of the words “frozen” and “fixed” are telling. These artists felt stifled and stagnant in their ivory towers—the ICA, the RCA, the Slade, the Courtauld. Dubuffet and Pollock might have offered these British artists a vehicle in which to escape. Indeed, perhaps it was because Dubuffet and Pollock were not British that they held special allure; they were anticultural as far as Britain’s borders were concerned.

Photographs may be frozen in time, but Henderson’s work proves to us that they can still have active lives. They can reinvent and procreate long past their moment of capture. The nimble photographer can reshape them, stretch them, recalibrate their borders. The open-minded curator can restructure their content through creative juxtaposition. Indeed, their reproducibility makes them mobile, and their mobility makes them street-smart.

Endnotes

[1] Peter Smithson and Alison Smithson, “But Today We Collect Ads,” Ark, no. 18 (November 1956).

[2] Smithson and Smithson, “But Today We Collect Ads.”

[3] Fathers of Pop, directed by Julian Cooper, written and narrated by Reyner Banham (Great Britain: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1979).

[4] Cooper and Banham, Fathers of Pop.

[5] Dislike for Herbert Read in particular was somewhat arbitrary and mostly symbolic. As Alloway recalls: “What bugged me about Herbert Read was his idealism, he was committed to a very idealistic aesthetic in which high tasks were assumed to be proper for art, and so much got neglected . . . it was kind of unfair of me to [oppose him] because he was always so nice and helpful to me . . . but there was nobody much else to attack.” Cooper and Banham, Fathers of Pop.

[6] Richard Hamilton remembers it this way: “I understood that the title ‘Independent Group’ came from the idea of rejecting the mother image of the ICA . . . it was a resentment of the ICA actually bringing all these people together at all. So we said, ‘All right, we’ll be together but we want to be independent of the ICA.’ ” Cooper and Banham, Fathers of Pop.

[7] Cooper and Banham, Fathers of Pop.

[8] Banham, for example, when defining the Smithsons’ architectural venture (which he called “New Brutalism”), found it easiest to do so in terms of fine art: “Non-architecturally it describes the art of Dubuffet [and] some aspects of Jackson Pollock . . . or Eduardo Paolozzi and Nigel Henderson among British artists.” In the sense that Dubuffet and Pollock were chosen to define the work of architects, the use of the word “buttress” is all the more apt. Dubuffet and Pollock, though foreign, became central to interpretations of the Independent Group in London. Banham, quoted in Ben Highmore, The Art of Brutalism: Rescuing Hope from Catastrophe in 1950s Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 29.

[9] It is worth noting that the current hanging at the Tate Modern in London positions paintings by the two artists side by side, indicating that their relationship has been particularly enduring.

[10] Dr. Kent Minturn identified the Dubuffet painting in email correspondence with the author, April 25, 2018.

[11] Henderson had a lifelong interest in biology. He wrote to Chris Mullen, “a small visual fever can come over me when I find drawings and sections of micro stuff.” Victoria Walsh, Nigel Henderson: Parallel of Life and Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 2001), 15.

[12] Guggenheim Jeune was a gallery venture located at 30 Cork Street in Piccadilly. It lasted two seasons, opening in January 1938 and closing its last show in June 1939. Its closure was in part due to the onset of the war, which saw Guggenheim leave Europe, and in part because it was wildly unprofitable—Guggenheim later disclosed in her memoir, Confessions of an Art Addict, that she lost roughly $6,000 dollars a month on its ambitious exhibitions. Peggy Guggenheim, Melvin P. Lader, and Fred Licht, Peggy Guggenheim’s Other Legacy (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1987), 30-39.

[13] Guggenheim, Lader, and Licht, Guggenheim’s Other Legacy, 30-39.

[14] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 15.

[15] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 15.

[16] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 19.

[17] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 8.

[18] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 30.

[19] Jean Dubuffet, “Art Brut in Preference to the Cultural Arts” (1949), trans. Paul Foss and Allen S. Weiss, Art & Text 27 (1988), 33.

[20] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 49.

[21] Roger Mayne came onto the scene slightly later, in the late 1950s.

[22] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 30.

[23] The affinity Henderson identifies here between crude machinery and drawing is echoed in the language he uses to describe a boy riding a bicycle in another series of his stressed images: the boy is “doodling.” Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 28.

[24] This was done “in order to stress a point or evoke an atmosphere.” Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 31.

[25] Dubuffet, “Art Brut in Preference to the Cultural Arts,” 31.

[26] Jean Dubuffet, “Notes for the Well-Read,” in Prospectus aux amateurs de tout genre (Paris: Gallimard, 1946), 69.

[27] Dubuffet, “Notes for the Well-Read,” 69.

[28] Aline B. Louchheim, “Americans in Italy,” The New York Times, September 10, 1950.

[29] Jeremy Lewison, “Jackson Pollock and the Americanization of Europe,” in Jackson Pollock: New Approaches, ed. Kirk Varnedoe and Pepe Karmel (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2000), 204.

[30] Dominic Sandbrook, Never Had It So Good: A History of Britain from Suez to the Beatles (London: Abacus, 2008), 127.

[31] John F. Lyons, America in the British Imagination: 1945 to the Present (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 8.

[32] One Briton, almost nine years after the war’s end, remarked, “Our precarious economic position today is in no small measure due to the fact that, in addition to the enormous financial calls upon us during the war years, we had to devote so much of our resources to pay for munitions of every kind to the U.S.A. which emerged from this war, as it did from the first, the richest and most powerful country in the world.” Lyons, America in the British Imagination, 37.

[33] “From hula-hoops to Zen Buddhism, from do-it-yourself to launderettes or the latest sociological catch phrase or typographical trick, from Rock ‘n’ Roll to Action Painting, barbecued chickens roasting on their spits in the shop windows to parking meters, clearways, bowling alleys, glass-skyscrapers, flying saucers, pay-roll raids, armored trucks and beatniks, American habits and vogue now crossed the Atlantic with speed and certainty that suggested that Britain was now merely one more off-shore island.” Harry Hopkins, quoted in Sandbrook, Never Had It So Good, 127.

[34] Horizon, a British cultural magazine, was founded during World War II by the journalist Cyril Connolly. Jeremy Lewison writes that it was “something of a barometer of intellectual views on America,” as it took a consistent interest in American events and characters. Lewison, “Jackson Pollock and the Americanization of Europe,” in Varnedoe and Carmel, Jackson Pollock, 202.

[35] Clement Greenberg, “The Present Prospects of American Painting and Sculpture,” Horizon 16 (October 1947), 26.

[36] “At the time, the importance of American art was not yet recognized, and the American art magazines, though available, were not yet read with the intensity of such French reviews as Cahiers d’Art. Writings on Pollock were therefore overlooked in the Britain of the early 1950s, and word of mouth was an important means of communication.” Lewison, “Pollock and the Americanization of Europe,” 205.

[37] Jean Dubuffet, “Anticultural Positions,” in Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternative Reality, ed. Mildred Glimcher (New York: Pace Publications, 1987), 127.

[38] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 53.

[39] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 53.

[40] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 49.

[41] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 49.

[42] Robin Kelsey, “Stalking Chance and Making News, c. 1930,” in Photography and the Art of Chance (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2015), 181.

[43] Kelsey, “Stalking Chance,”181.

[44] Quoted in Kelsey, “Stalking Chance,” 201.

[45] Dubuffet, “Notes for the Well-Read,” 71.

[46] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 54.

[47] Kelsey, “Stalking Chance,” 201.

[48] Walsh, Nigel Henderson, 54.

[49] Hal Foster, “Savage Minds (A Note on Brutalist Bricolage),” October, no. 136 (Spring 2011): 185.

[50] Quoted in Lewison, “Pollock and the Americanization of Europe,” 204.

Author Bio:

Phoebe Herland is a PhD student at the Institute of Fine Arts. Her scholarship focuses on post-war British and American art, with particular interest in cross-cultural exchange between London and Los Angeles. Since receiving her undergraduate degree from Bard College in upstate New York, Phoebe has held positions at the Guggenheim, the Armory Show, and Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York City. She may be reached at psh286 at nyu.edu.