Katherine Parks

The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Abstract

The Description de l’Égypte is an encyclopedia of the findings of Napoleon’s army in Egypt during their 1798–1801 invasion and occupation. In this paper, I compare the original drawings produced in Egypt with the final prints and the ancient monuments. After careful consideration of the artist materials used to create the Description, this study reveals instances in which the savants and the engravers exerted creative agency over the content, composition, and style of the printed images. I argue that these examples highlight the imperial narrative of the work and its Orientalist underpinnings while also serving to discredit French claims of objectivity in representation.

![]()

Engraving Egypt: Drawings, Prints, and Authorship in the Description de l’Égypte

The Description de l’Égypte, ou, Receuil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’armée française is a 24-volume encyclopedia that details the scientific findings of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) and his army during the 1798-1801 French invasion, occupation, and exploration of Egypt. The Commission des Sciences et des Arts d’Égypte accompanied the army with the mission of documenting and disseminating information relevant to Napoleon’s political and military campaigns. The Commission, known collectively as the savants, consisted of 150 engineers, artists, scientists, and architects. During the occupation, the savants produced detailed notes, sketches, and maps of Egyptian monuments which would form the intellectual basis of the Description de l’Égypte.

In 1801, when Napoleon’s generals capitulated to Admiral Nelson and abandoned Egypt, the British took possession of the antiquities gathered by the French, most notably the Rosetta Stone. However, the French were permitted to keep their notes, sketches, and other papers. In 1802, Napoleon declared that the findings of his army would be published at the government’s expense as a massive, multi-volume illustrated book. The Description de l’Égypte is divided into three sections: antiquities, natural history, and the modern state. The complete set consists of nine volumes of text, fourteen volumes of prints, and the Explication des planches – a text directory to the plates. Although 1,000 engravings were proposed, only 837 engravings were produced in total. The French government sub-contracted the production of the plates to five printmakers in Paris.[i] The ten volumes of explanatory text were published by the Imprimerie Impériale (later the Imprimerie Nationale). The first volume was available to subscribers in 1809 and the final volume was published in 1829.

The Description de l’Égypte, considered to be the first major text in Egyptology, is believed to have influenced the trajectory of the discipline even before the translation of the hieroglyphs by Jean-François Champollion in 1822. However, historians David Prochaska and Anne Godlewska argue that the Description de l’Égypte reveals more about its French authors than it does about Egypt. Prochaska reads the plates as examples of cultural orientalism in both the political and intellectual realm.[ii] He concludes that the knowledge-gathering activities of the savants actively supported Napoleon’s military and imperial ambitions. Godlewska examines the maps of the Description and identifies the goals of the cartography within the ideology of empire.[iii] She notes how the French believed that the monuments of ancient Egypt were a testament to singular strength of the pharaoh, a leadership model Napoleon sought to emulate. She observes that the French chose to record elements that highlight civic strength, yet ignored those that show ruin, neglect, and vestiges of Mamluk rule in Egypt.

In the Preface to the Description, Joseph Fourier, a mathematician and the first editor of the Description, poetically links conceptions of empirical truth with the art of engraving. Godlewska writes that for Fourier: “truth was largely assumed to be synonymous with science…[Fourier] makes it clear that the mission of the text is scientific representation. If something could be represented with precision, detail, or accuracy it clearly had the value of truth. The ultimate in truth was reproducibility.”[iv]

Fourier’s position is grounded in the Enlightenment notion that truth could be conveyed by representation and images. The engravings of the Description, based on the drawings produced in Egypt by the savants, led them to claim scientific objectivity.

While the Description de l’Égypte is a masterpiece because of its scale, the technical supremacy of its engravings, and its overall beauty as a work of art, it cannot be read as an objective representation of Egypt during the French invasion. I suggest the artistic techniques used to translate stone monument to print reveal the culturally constructed biases of its authors. The choices made by the savants and the engravers were motivated by the imperial narrative predominant in Napoleon-era France. These examples demonstrate how the engravers actively contributed to the content and composition of the prints. As a result, any study of the Description is incomplete without acknowledging the interventions and hidden intentions of the authors.

In this paper I consult the preliminary drawings sketched by the savants in Egypt. Of the 816 drawings held and digitized by the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), this article examines 10 drawings and their related prints. The study is limited to just three sites – Philae, Medinet Habu, and Karnak. Philae, the first site presented in the Description, is notable for scholars as an early document of its pre-flood condition. The site suffered from frequent flooding since the construction of the Aswan Low Dam in 1902. The Philae temple complex was dismantled and relocated to a neighboring island prior to the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1970. Medinet Habu and Karnak were selected because the sites have been well-documented by archeologists. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago recorded and published the reliefs at Medinet Habu and Karnak as part of their epigraphic survey of Egyptian monuments.

Several institutions have digitized their sets of the Description de l’Égypte. In this paper, I consult the high-resolution tiff images of the prints from the New York Public Library. The original drawings are held in the BnF and are available to view online. Although I have viewed several volumes of the Description de l’Égypte in person at The Explorer’s Club in New York City, in this article my primary method of studying the prints and drawings was by viewing the digital downloads in Adobe Photoshop using the zoom tool for magnification. As a result, I cannot comment on the effects of the various papers used for the prints and drawings, nor can I make any claims about the scale of the drawings in comparison to the printed images. However, the digital nature of my investigation has allowed a sustained examination of the drawings and prints under intense magnification and a direct side-by-side comparison that would not have been otherwise possible in the reading room.

As prints are not objective, I suggest that engraving should be understood as a fundamentally interpretive medium. The technical process of engraving reduces drawings to patterns of lines and dots. These lines suggest shape, shading, value, and color. A substantial amount of translation was required by both the savant and engraver to represent three-dimensional stone carvings on a two-dimensional sheet of paper. Therefore, it is useful to begin this discussion by examining the various media used to create the images within the Description.

Many of the drawings produced by the savants in Egypt were made with crayon noir. In contemporary French, crayon translates to pencil. However, in the late eighteenth-century, crayon denoted the invention of Nicolas-Jacques Conté (1755–1805), the scientist and inventor best known for inventing fabricated graphite, called the conte crayon. He was also an early member of Napoleon’s scientific commission in Egypt. Previously, graphite had been manufactured by the English, by using mined plumbago to create a drawing medium. In contrast, Conté combined clay, powdered graphite, and lampblack to produce graphite rods. He was issued a patent for his invention in 1795 and manufactured the rods in several levels of hardness and blackness.[v] Conte crayons were quickly adopted by artists, writers, and those engaged in technical drawing.[vi] Conte crayons were preferred by technicians because they were manufactured to be consistent and permanent. English pencils made with mined leads could be erased from paper with breadcrumbs whereas the conte crayon could not. In this way, in the words of Richard Taws, “…Conté’s pencils stopped time. Their marks were indelible, as permanent as an engraving.”[vii]

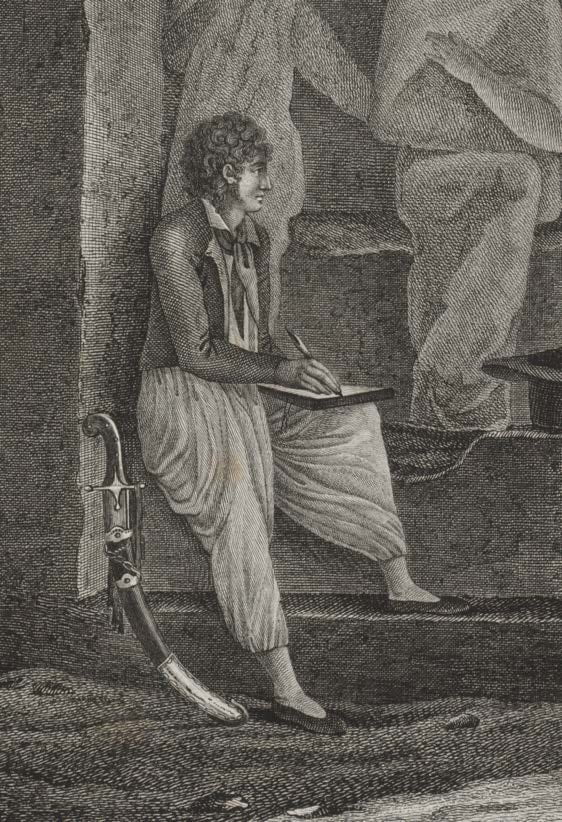

Some of the prints in the Description show the savants at work recording the monuments. The savants are depicted facing the monument with their drawing board, often wearing a top hat and coat. This type of human staffage was frequently used in architectural drawings to provide both scale and context to the monuments. For example, in plate 67 (Fig. 1) there is a savant sketching the temple of El-Kab holding a double ended porte-crayon in his hand. In the eighteenth-century, graphite rods were not encased in wood (the form of the modern-day pencil). Rather, the rods were held in a device called a porte-crayon. The claw grips at either end of the device held an un-encased piece of crayon. These vises were made from wood and later metal.[viii]

Fig. 1 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 67. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Gilbert-Joseph-Gaspard de Chabrol de Volvic (1773–1843), a civil engineer, used crayon almost exclusively for his drawings. Chabrol, a graduate of the École polytechnique and a member of Napoleon’s team, designed bridges and roads to transport military equipment and personnel.[ix] Chabrol would have been trained in the principles of descriptive geometry at the École polytechnique. Descriptive geometry was developed in the eighteenth-century by Gaspard Monge, a founder of the École polytechnique. Descriptive geometry claims to be equal part art and science, applying mathematical rigor to the practice of drawing.[x] This method for rendering three-dimensions in only two was adopted by architects, surveyors, and engineers to record objects and buildings on paper with detail and precision. In this manner, descriptive geometry was deemed the most truthful method of representation because the “…association with measurement mathematics and observational instrumentation … lent [the images] apparent objectivity.”[xi]

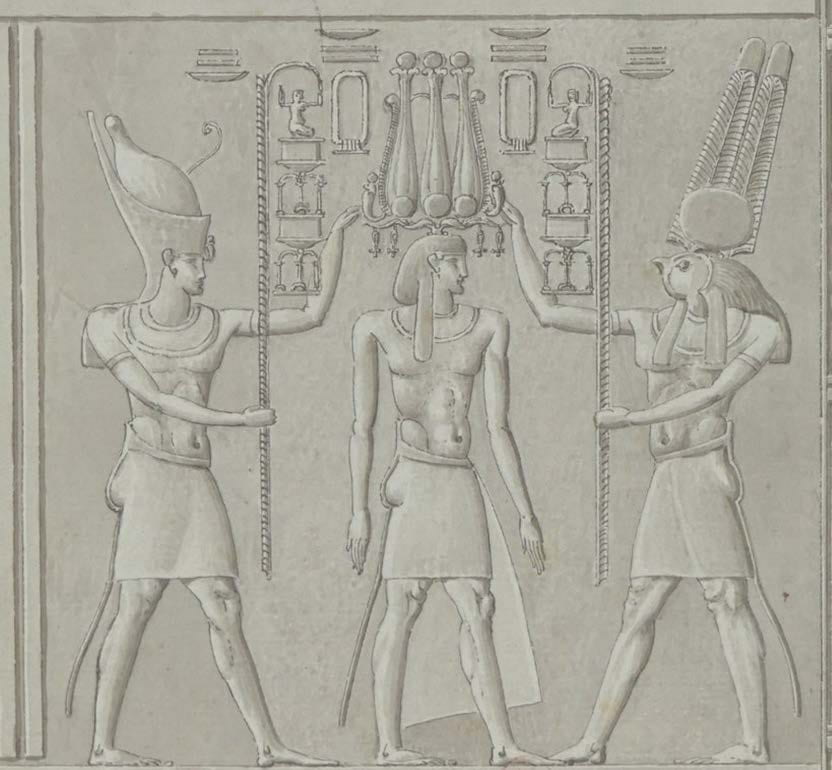

Chabrol’s training in descriptive geometry is apparent when examining one of several sketches of wall relief from Philae (Fig. 2). His system for creating tonal effects is schematic and simple; it communicates depth with flat layers of highlight, mid-tone, and shadow. Chabrol used the side of a pencil to create an overall mid-tone, almost like a ground, on the paper. Highlights were subtracted by erasing the mid-tone and shadows were rendered by additional shading in pencil. Chabrol does not include additional shading to define the musculature of the figures. This drawing is reproduced in Plate 22 of Volume I of the Description, along with other small reliefs sketched by Chabrol (Fig. 3). The engraving was meant to be understood as a perfect reproduction of the drawing, which in turn was a perfect reproduction of the carving. In the early modern period, engraving was considered a mimetic method of reproduction. Engraving was understood by some as a reproductive technology, rather than an artistic medium. Indeed, the Printmaking Bible states, “…the stylized nature of the prints reduced the art of engraving to one of reproduction rather than that of a medium capable of creative or original design.”[xii] The engraver is not an artist, but rather a craftsman or artisan. Image quality is measured by technical excellence.[xiii] Additionally, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, engraving was sometimes regarded as merely mechanical and uninventive.

![Fig. 2 Chabrol de Volvic, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs du temple de l'ouest], 1798-1809, crayon noir et plume, 27.8 x 44.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-2-1024x694.jpg)

Fig. 2 Chabrol de Volvic, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs du temple de l’ouest], 1798-1809, crayon noir et plume, 27.8 x 44.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 3 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 22. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

For example, the engraving of Chabrol’s drawing reproduces the tonal effects of the conte crayon in two ways. The figures are rendered with stipple engraving. To create this effect, the engraver would use a burin to gouge out a pattern of dots to create passages of tone. By increasing the density of dots, the engraver could suggest an increase in value. Parallel lines imitate the flat wall. Stipple and line are used together, even though Chabrol’s shaded mid-tone does not graphically differentiate a change in the surface of the stone carving.

In the engraving, the wall may have been rendered exclusively in lines because it created less work for the engraver. Conté developed an engraving machine that could render perfectly straight lines that were spaced at regular distances. His machine reduced the work of eight months to just two or three days.[xv] This technique was especially effective for depicting the vast cloudless Egyptian sky. Richard Taws writes that “the uncannily serene visual effect [the engravers] created, generated a strangeness all their own.”[xvi] The regular lines appeared highly mechanical to Western viewers. The perfectly straight lines of the wall suggest a perfectly smooth, flat stone surface. However, in reality, the sandstone surfaces of Philae were damaged from frequent flooding. Ultimately, the overall effect of the parallel lines is one that separates the wall relief from its context as part of an ancient monument.

Other savants received their artistic training outside of the École polytechnique, such as Charles Louis Balzac (1752–1820), an architect and artist. As a painter, Balzac exhibited at salons during the French Revolution.[xvii] Balzac primarily used lavis d’encre, or ink wash, for his drawings. In contrast to crayon, which is a dry medium, ink is a wet medium. Ink is a fluid suspension of fine particles in water and a binding medium. Inks are generally applied with a nibbed pen but can be thinned with water and applied with a brush, known as wash. Balzac also used aquarelle, or watercolor. Watercolor is a paint medium of pigment powder, water, and a gum binder. It is applied as transparent washes with soft sable brushes. As a result of using wet media in his works, Balzac’s style is distinctly more painterly than that of Chabrol, as seen in his relief from Philae (Fig. 4). Although Balzac used the same general principles of highlight, mid-tone, and shadow as Chabrol, Balzac applied darker washes to accentuate subtleties of the stone surface and the musculature of the figure. The final engraving (Fig. 5) uses the same convention of stipple for the figures and line for the walls as seen above. Where Balzac has rendered shadow, the stippling is denser. In this manner, the engravings neither imitate the drawing media nor differentiate wet or dry application.

Fig. 4 Charles-Louis Balzac, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-relief du Grand temple], 1798-1809, aquarelle,

lavis d’encre et plume, 15.6 x 20.1 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 5 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 12. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

One of the most obvious changes between Balzac’s drawings and the final engravings concerns facial details. Unlike Chabrol who meticulously rendered the faces in sharp pencil, Balzac used ink and wash to casually suggest features. The eyes are reduced to lines; nostrils and lips are omitted. Yet, the final engravings include facial details not depicted in Balzac’s original sketches. The faces are styled to resemble those drawn by Chabrol. As seen previously, Chabrol paid particular attention to the finest of details, especially in the faces and headgear. His high level of detail was retained almost exactly in the engravings.

In another sketch by Balzac of Philae (Fig. 6), small figures are rendered with thick brushed lines and as such, the facial features are vague. Wash is used to render the shadow of eye sockets and the area under the cheekbone. However, as above, the engravers extrapolated from the sketches and included simple facial details, such as rounded noses and smiles with upward turned lips (Fig. 7). Very little of Balzac’s shading technique of the figures is retained in the engravings. Unlike the previous reliefs, the engravers used parallel lines to render both figure and wall.

![Fig. 6 Charles-Louis Balzac, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs de l'édifice de l'ouest], 1798-1809, aquarelle, lavis d'encre et plume, 21.4 x 27.1 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-6-1024x678.jpg)

Fig. 6 Charles-Louis Balzac, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs de l’édifice de l’ouest], 1798-1809, aquarelle, lavis d’encre et plume, 21.4 x 27.1 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 7 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 19. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York

Public Library, New York, NY.

More than 400 printmakers were employed over the course of the twenty-year production of the work. At the bottom of each print, the author of the drawing is acknowledged as well as an engraver. However, each print produced for the Description was the result of many hands, with each member of the printshop contributing a particular skill or area of expertise. There was a need to maintain consistency in all the images, especially considering that five different print shops were tasked with producing the plates. The regularizing of the features was likely part of a conscious effort to create a unified style that could be replicated over the course of many years and many volumes.

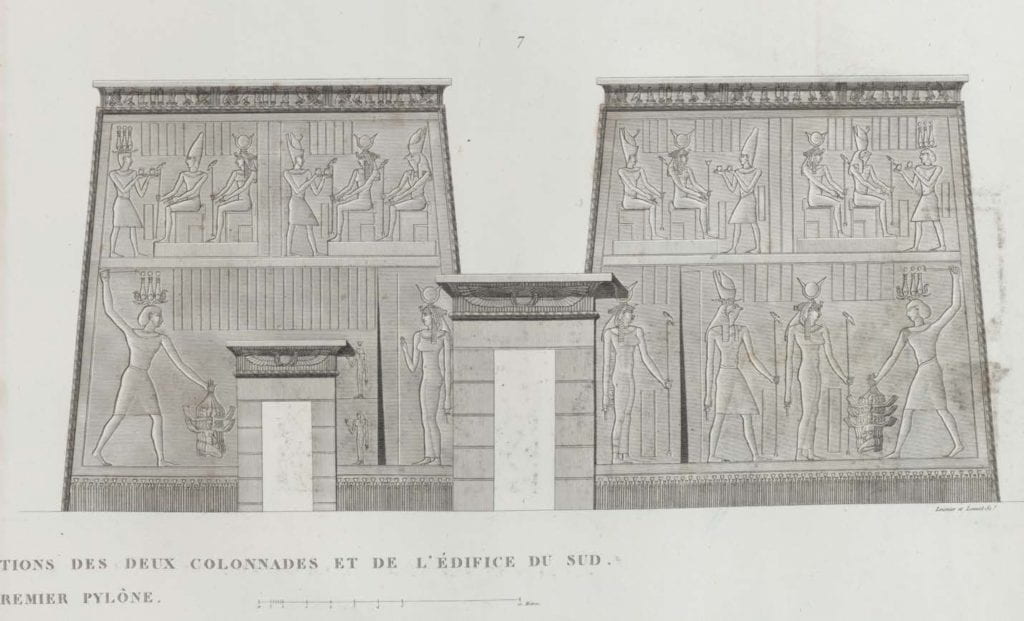

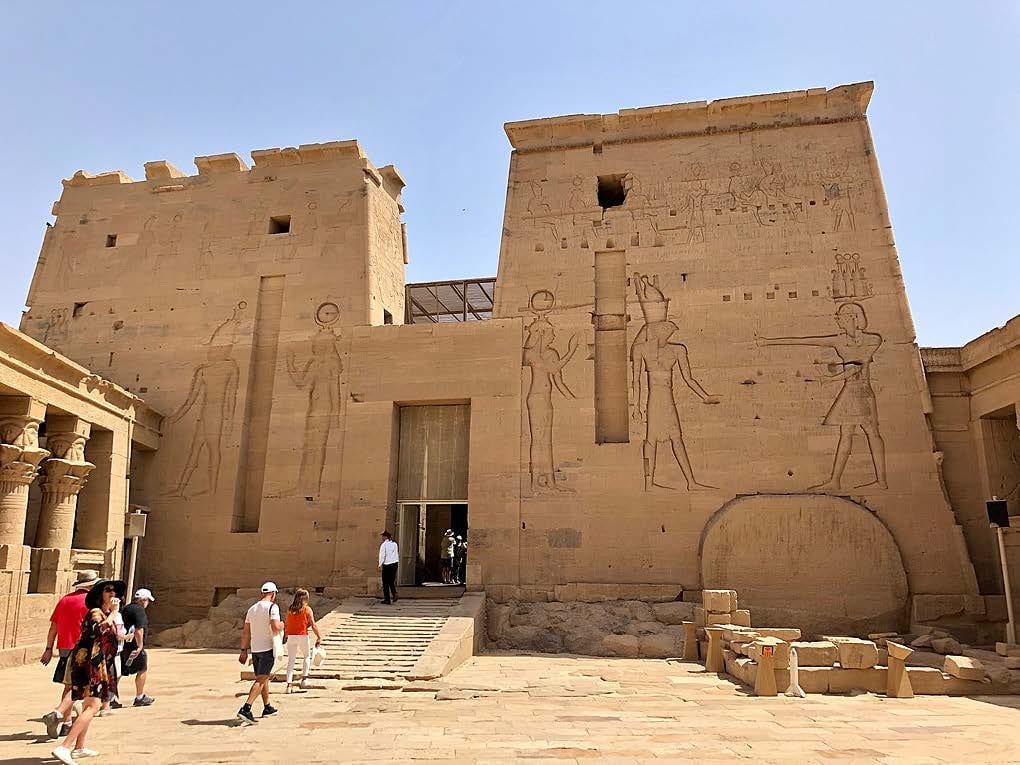

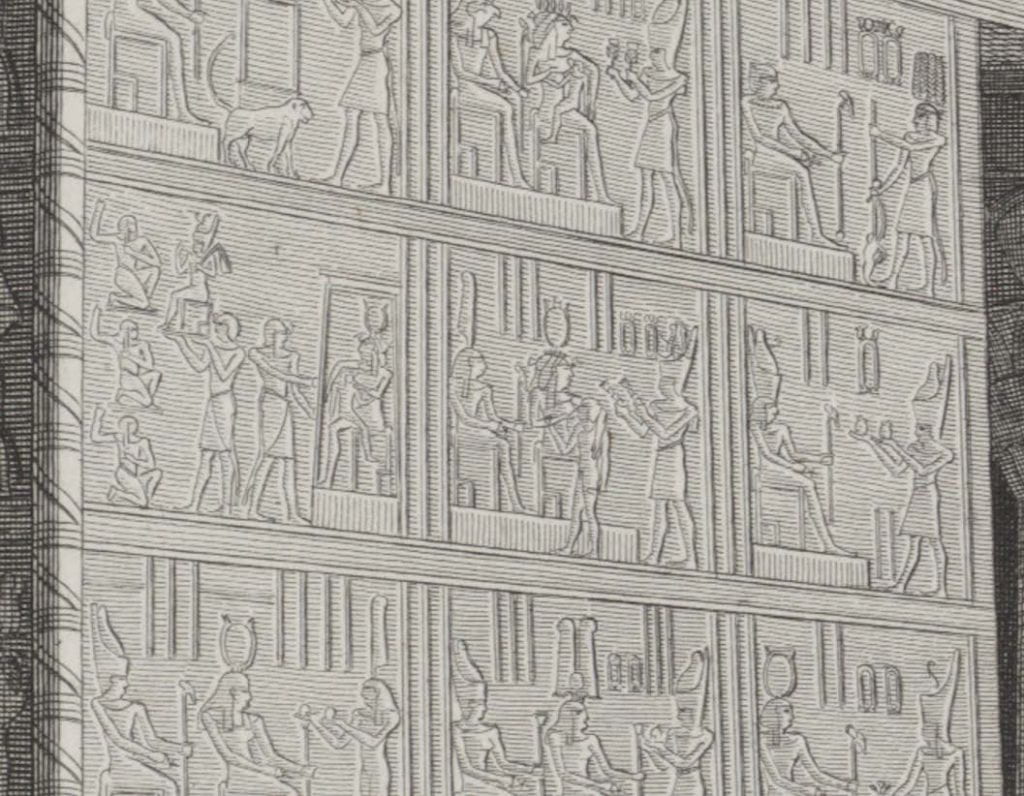

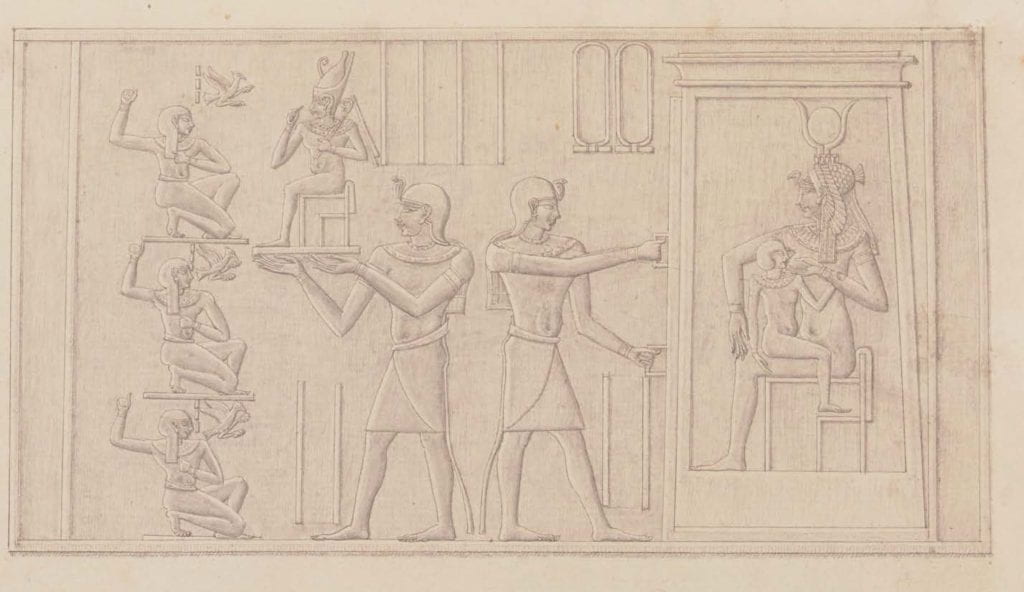

Descriptive geometry was designed to render Western architectural styles. As a result, it is limited in its ability to express Eastern styles and features. Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois (1776–1842) and Édouard de Villiers du Terrage (1780–1855), both civil engineers at the École polytechnique, produced this measured drawing of the first pylon of the Isle of Philae (Fig. 8). At first glance, both the preliminary drawing and the engraving (Fig. 9) suggest that the wall carvings are rendered bas-relief. A controlled combination of stipple, line, and shading were employed to show the dimensional differences of the wall surface. However, this photograph (Fig. 10) reveals that the carvings on the pylon are, in fact, sunk relief rather than bas-relief. With sunk relief carving, the wall surface is left flat and the area around the forms is removed. The forms within the carved area are rendered in low relief, the highest point of which never goes beyond the plane of the wall surface. Sunk relief creates strong shadows around the figures depending on the time of day and angle of the viewer, as seen in the photograph. The style is mostly limited to Egyptian art, so the Western system of descriptive geometry lacked graphic conventions for adequately expressing the peculiarities of sunk relief. This salient feature of Egyptian sculpture was, in a sense, lost in translation.

![Fig. 8 Jollois et de Villiers, [Ile de Philae] : [dessin], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre et crayon. No dimensions provided. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-8.jpg)

Fig. 8 Jollois et de Villiers, [Ile de Philae] : [dessin], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre et crayon. No dimensions provided. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 9 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 6. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Fig. 10 Ryckaert, Marc, Aswan (Egypt): Philae Temple – first pylon, 2012, digital photograph. Wikimedia Commons. <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Philae_Temple_R02.jpg>

Jollois and de Villiers misrepresented the first pylon in their drawing in more consequential ways. Most notably, the photograph shows a smaller structure, known as the Gate of Ptolemy II, that blocks the full view of the relief. Several figures’ gestures have been altered. For example, the two servants on the left side of the pylon are carved with open, flat palms. However, in the drawing, these same figures have their fists closed around small bottles. In the engraving, the servants have open palms, but are carrying the small bottles. On the right side of the pylon, one of the servants has crossed arms. In both the drawing and the engraving, the figures’ arms are uncrossed. These examples are minor instances of a phenomenon that is quite common throughout the Description de l’Égypte; the savants were not always diligent about transcribing exactly what they saw.

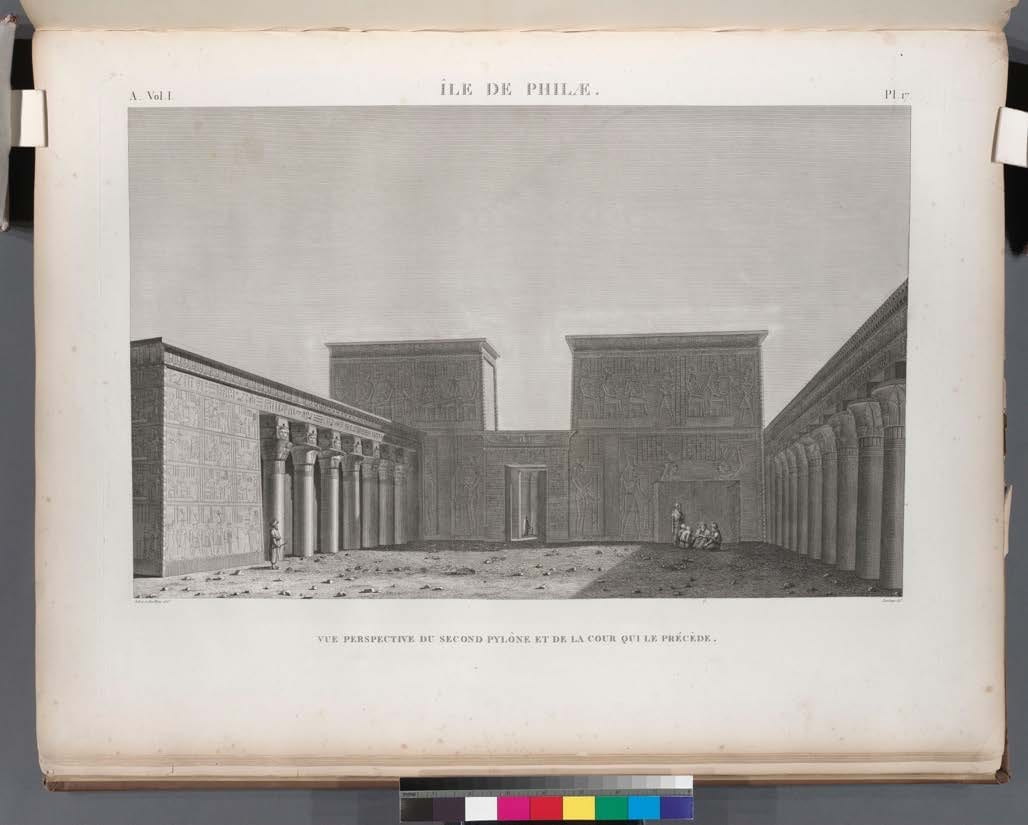

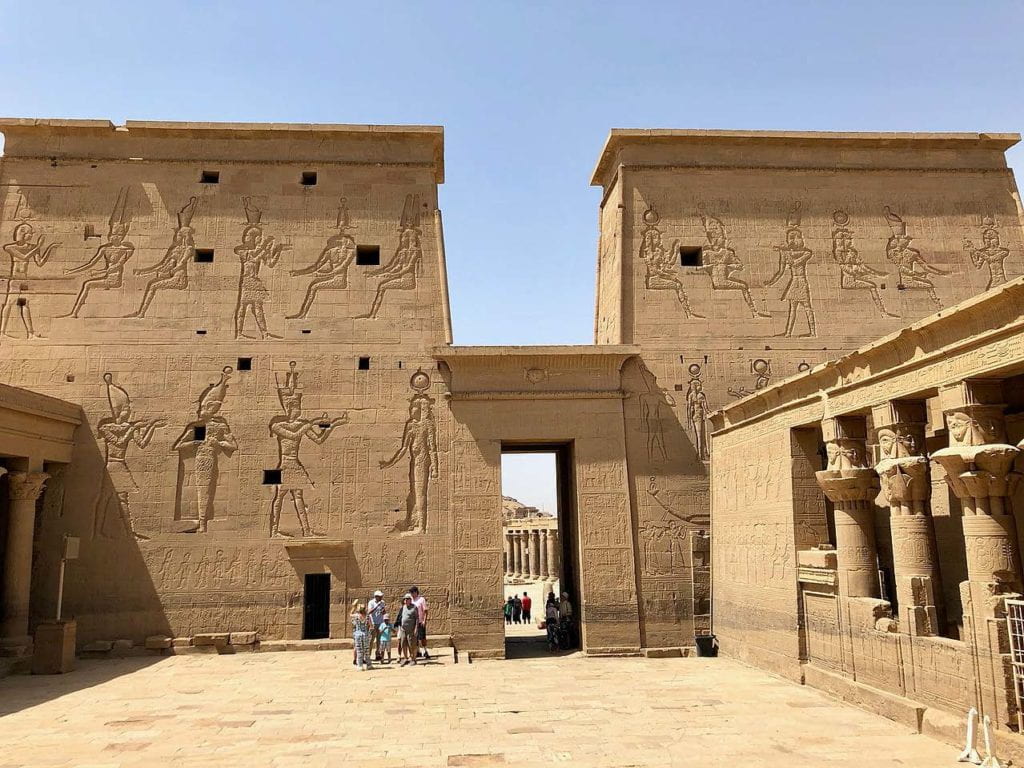

Plate 17 (Fig. 11) and its corresponding drawing (Fig. 12) depicting the second pylon at Philae differs from the monument (Fig. 13) so substantially, one must question if this drawing was produced in the presence of the monument or instead from a less-than-perfect memory. The figures in the upper frieze are substantially smaller on the monument than as depicted in the drawing, although the gestures and dress are accurate. The entryway of the drawing has an ornamental lintel which is not a feature of the actual monument. These alterations only make sense after examining the backside of the first pylon (Fig. 14). The proportion of the figures in the upper frieze and the entryway more closely resemble the first pylon than the second. One could speculate that this drawing is a patchwork of several different sketches made at Philae that were combined inaccurately to create a complete view of the pylon for publication.

Fig. 11 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 17. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

![Fig. 12 Jollois et de Villiers, [Ile de Philae] : [vue perspective du second pilône et de la cour], 1798- 1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 25.5 x 45 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-12.jpg)

Fig. 12 Jollois et de Villiers, [Ile de Philae] : [vue perspective du second pilône et de la cour], 1798- 1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 25.5 x 45 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 13 LeMay, Warren, Temple of Isis, Philae Temple Complex, Agilkia Island, Aswan, AG, EGY, 2019, digital photograph. Wikimedia Commons. <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_of_Isis,_Philae_Temple_Complex,_Agilkia_Island,_Aswan,_AG,_EGY_(48027128182).jpg>

Fig. 14 LeMay, Warren, Temple of Isis, Philae Temple Complex, Agilkia Island, Aswan, AG, EGY, 2019, digital photograph. Wikimedia Commons. <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_of_Isis,_Philae_Temple_Complex,_Agilkia_Island,_Aswan,_AG,_EGY_(48026992296).jpg>

Generally, the sketch and the engraving are in line with one another. The architectural features, columns, and capitals are captured by the print in detail. The sky consists of perfectly straight, parallel lines — a product of Conté’s engraving machine. Where Jollois and de Villiers use watercolor wash for tone and value, the engravers use crosshatched perpendicular lines. However, Plate 17 from Philae deviates from the original sketch in two ways that clearly demonstrate the influence of the engraver on the content of the final image. The print depicts relief around the central portico that is not included in the drawing. There is also an additional wall relief on the left side of the image that is not depicted in the sketch, nor on the monument. The engravers likely added these reliefs to fill empty space and to increase the size of the printed image so that it filled the whole page. Figure 15, a detail of Plate 17, shows this relief on the wall extension supplied by the engravers. The engraver recycled this image from a sketch from Philae made by Chabrol (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 17. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Fig. 16 Chabrol de Volvic, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs du temple de l’ouest], 1798-1809, crayon noir et plume. 27.8 x 44.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Linda Nochlin in her essay “The Imaginary Orient” discusses the use of authenticating details by Orientalist artists. Nochlin states that “the major function of gratuitous, accurate details … is to announce ‘we are the real.’ They are signifiers of the category of the real, there to give credibility to the ‘realness’ of the work as a whole, to authenticate the total visual field as a simple, artless reflection.”[xx] I suggest that much like how the Orientalist painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema included objects from the Egyptian galleries of the British Museum in his paintings, the engravers of the Description included reliefs from elsewhere in the work to add “realness” to what is in reality pure creation.

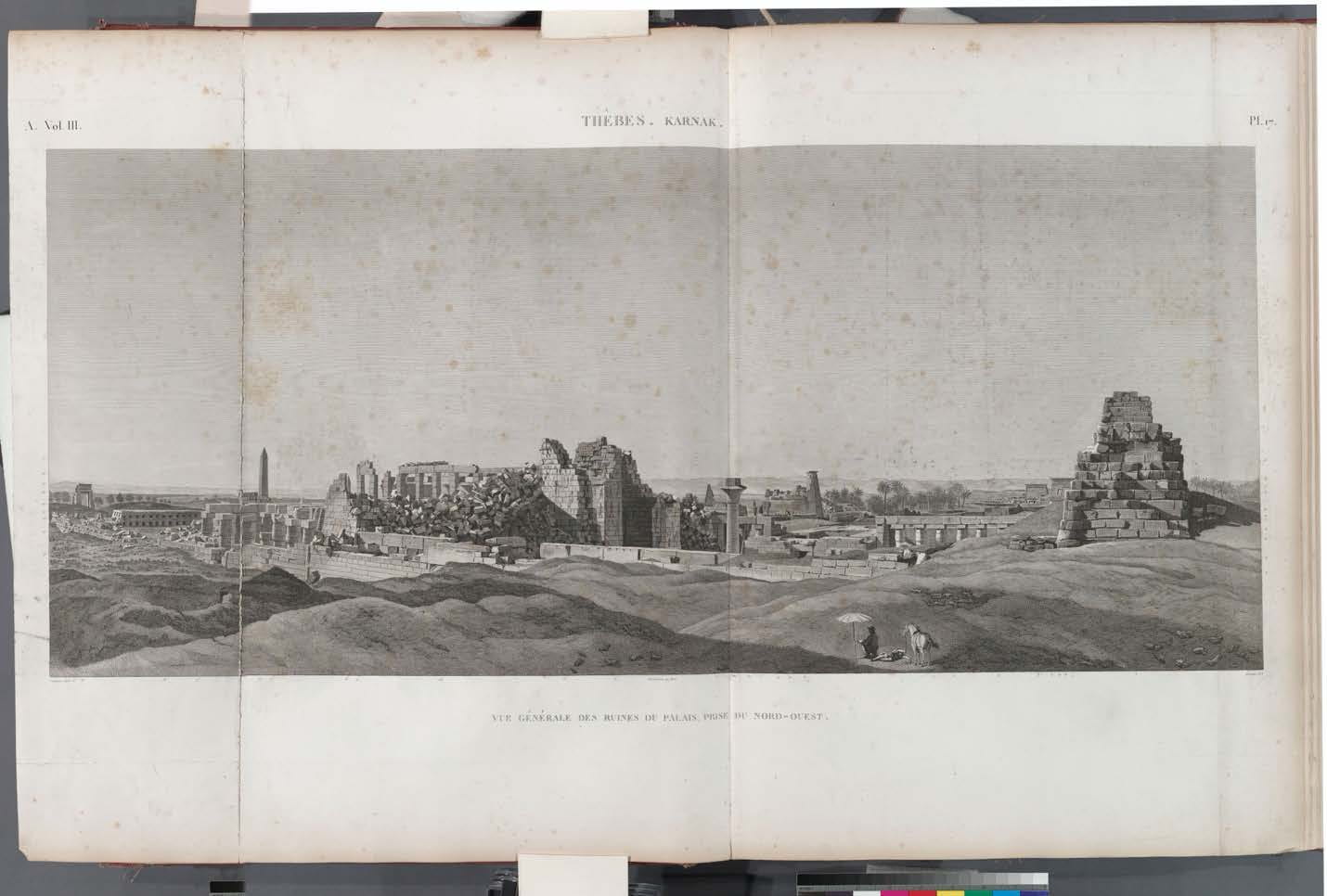

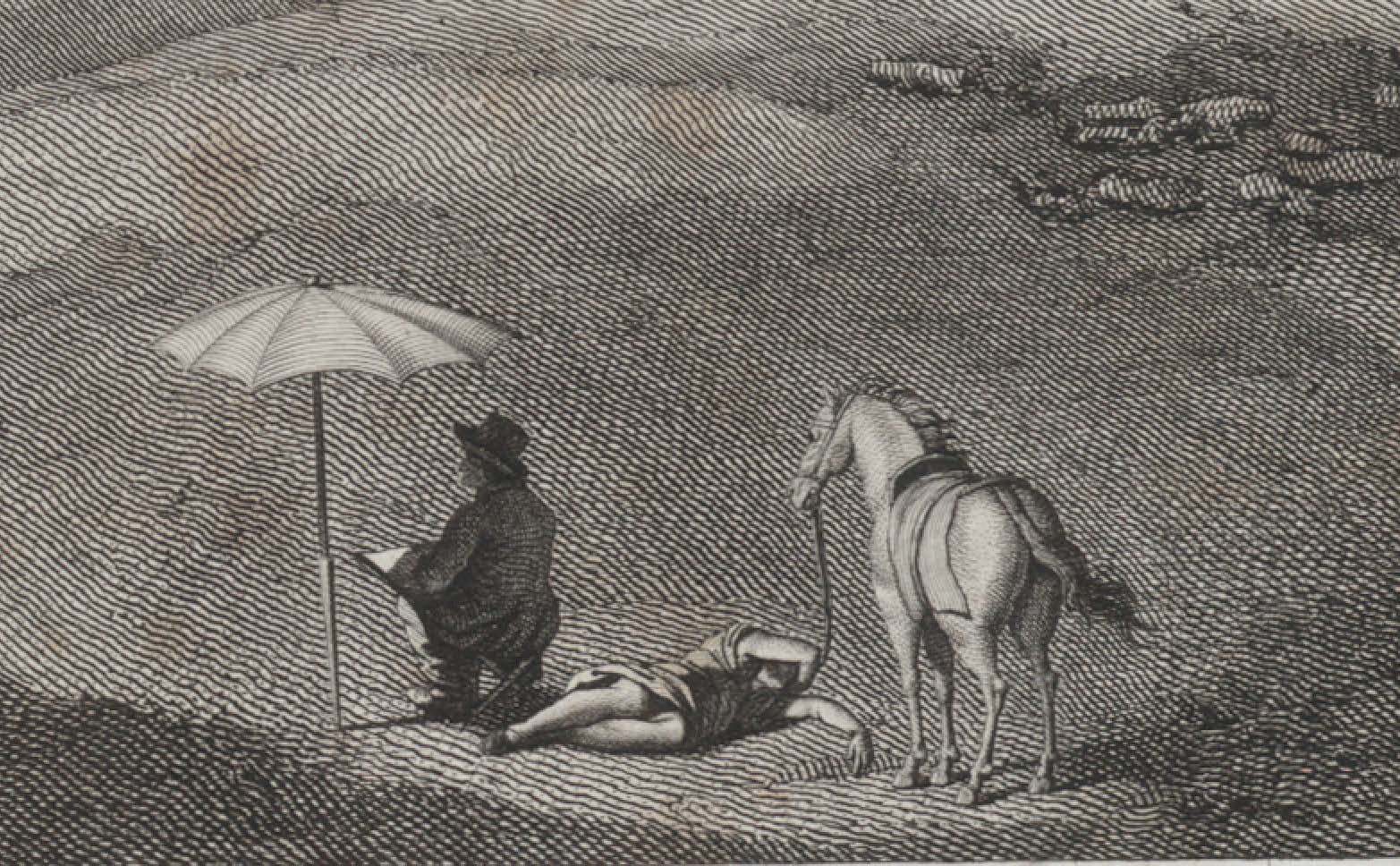

In fact, many prints are a collage of several sketches, often produced by different savants. Plate 17 from Volume III is a landscape scene of Karnak (Fig. 17). In the foreground of the print (Fig. 18), a savant is seen sketching next to a female sprawled seductively on the sand holding onto the reins of the horse. Of this vignette, Godlewska writes, “Here fantasy, the erotic and the exotic are all combined to relieve any tedium attached to antiquities. It also suggests, however, something of the complex motivations and emotions associated with the conquest of Egypt.”[xxi] Godlewska attributes the female odalisque to André Dutertre, the savant responsible for the drawing. However, these figures are not in Dutertre’s original drawing (Fig. 19); they had been copied from a sketch by François-Charles Cécile (1766–1840), a mechanical engineer (Fig. 20). This sketch has no context, and it is not clear if it was drawn at Karnak. Yet, it was included in the scene to add visual interest to the landscape while also maintaining the illusion of ‘the real.’

Fig. 17 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 17. Vol. III, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Fig. 18 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 17. Vol. III, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

![Fig. 19 Dutertre, [Karnak] : [vue générale des ruines du palais, prise du nord-ouest], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-19-1024x397.jpg)

Fig. 19 Dutertre, [Karnak] : [vue générale des ruines du palais, prise du nord-ouest], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

![Fig. 20 Cécile, [Dessinateur à l’ombre d’un parasol], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre et plume. 11.3 x 11.9 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-20-967x1024.jpg)

Fig. 20 Cécile, [Dessinateur à l’ombre d’un parasol], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre et plume. 11.3 x 11.9 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

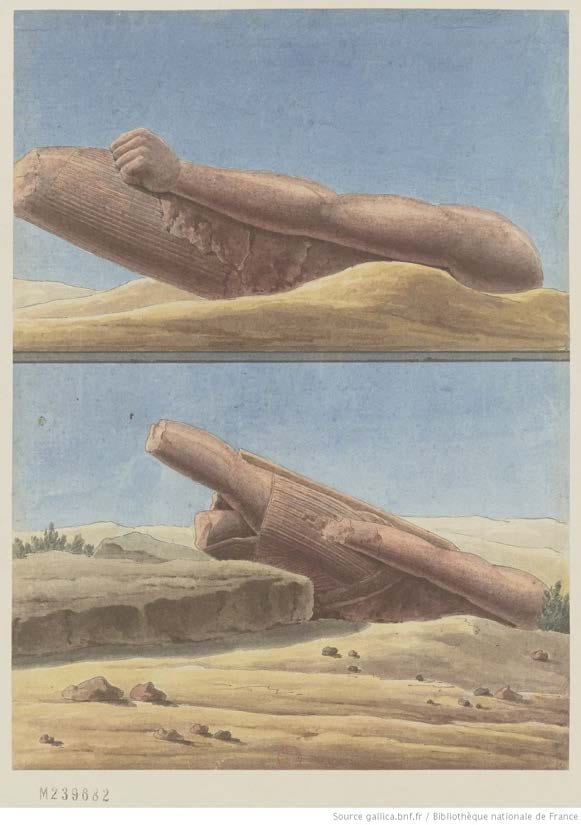

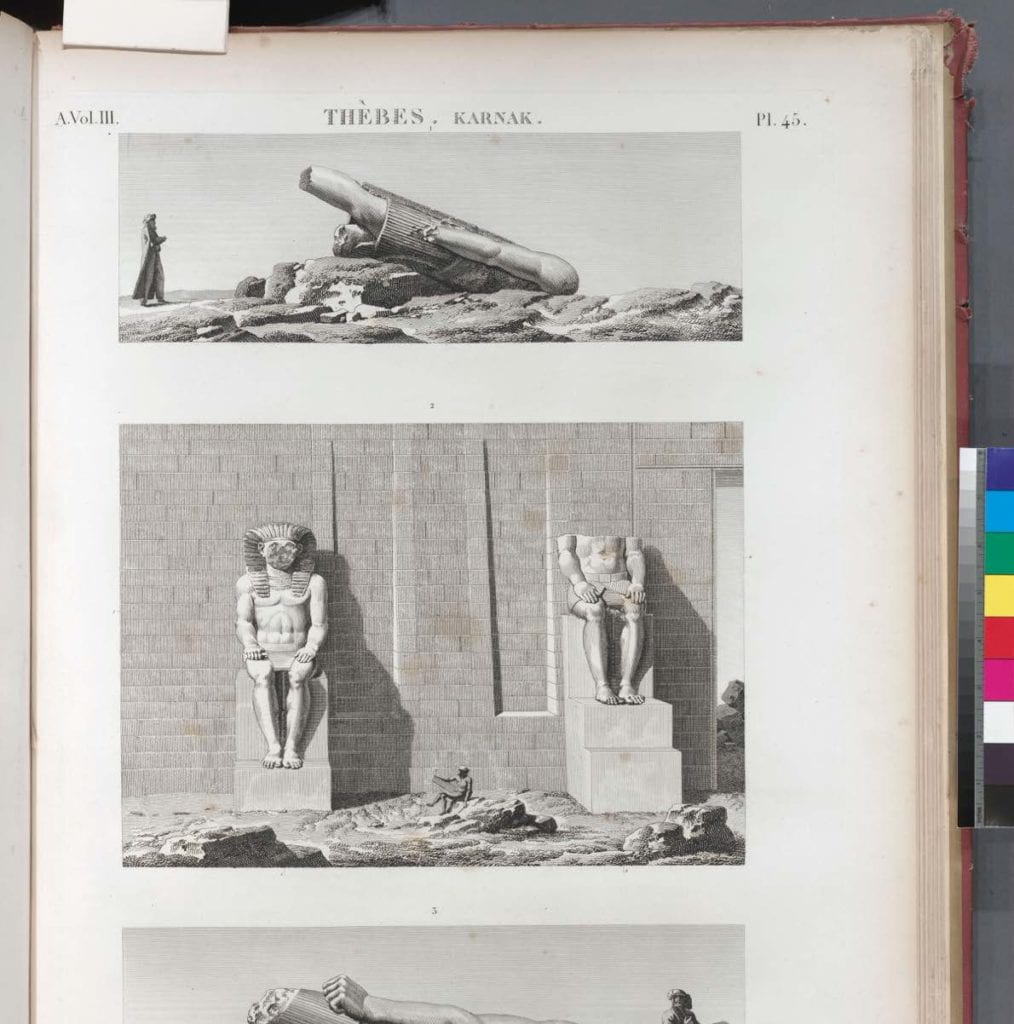

Fig. 21 Charles-Louis Balzac, [Karnak] : [fragments de colosses trouvés dans l’enceinte sud], 1798- 1809, aquarelle et plume. 27.5 x 20 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 22 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 45. Vol. III, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

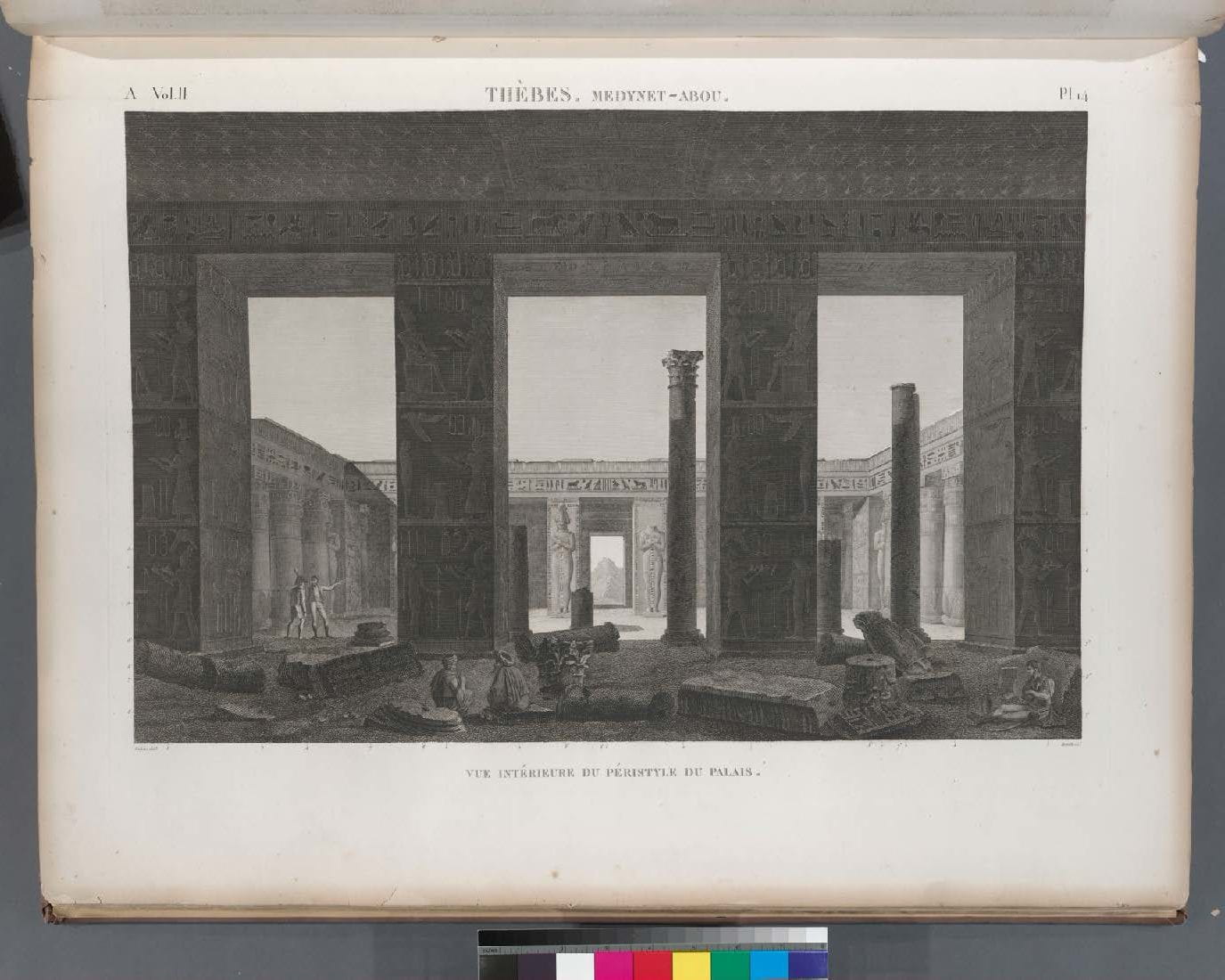

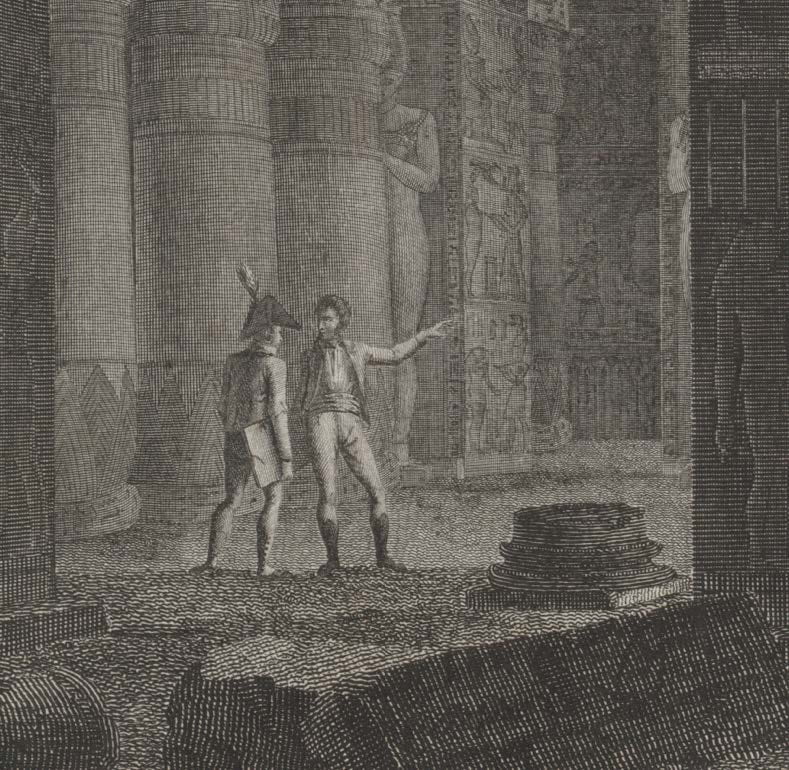

The creative agency of the engravers is most evident in the scenic depiction of the inner court of the temple at Médinet Habou. Plate 14 (Fig. 23) was engraved by Reville, based on a drawing by Balzac. The drawing (Fig. 24) is markedly different from the print. Several key architectural features have been reversed as well as the position of the figures in the foreground. In the engraving, the two columns have switched sides as well as the statues flanking the entrance to the second court. The pair of savants has changed positions with the seated savant. The fragments of statuary on the ground have shifted in relation to the figures. A possible explanation for these adjustments is that intaglio images print in reverse. When preparing the plate, the engraver draws the images in reverse so that the printed image is in the correct orientation. This engraver may have neglected to take this into consideration when transferring the drawing to the plate, due to inexperience or for another technical reason. Yet, the midground temple scenery from the drawing was not reversed accordingly in the print. The left side of the drawings does not correspond to the right side of the print and vice versa. In fact, close examination reveals that the architectural features of the temple do not follow Balzac’s record. One can interpret these adjustments as an attempt to compress the drawing, which is wider than the printed image. The drawing was compressed by the engravers to make the most use of the available space on the printed page.

Fig. 23 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 14. Vol. II, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

![Fig. 24 Balzac, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-24-1024x714.jpg)

Fig. 24 Balzac, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

![Fig. 25 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-25.jpg)

Fig. 25 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 26 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 14. Vol. II, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

![Fig. 27 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-27.jpg)

Fig. 27 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 28 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 14. Vol. II, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

The Egyptian figures have also been altered for the engraving. In the drawing (Fig. 29), both men are bearded and wear trousers, a long-sleeved shirt, and a vest. The figure on the right wears a turban and smokes a long pipe. The figure on the left wears a Western style hat with a wide round brim, suggesting that he may in fact be French. In the engraving (Fig. 30), both men wear traditional Muslim garments, consisting of billowing tunics and turbans. Prochaska notes that nowhere in the Description are French and Egyptian figures shown interacting. He also notes that they are most often placed in different quadrants of the scenes. If they are depicted in proximity to one another, the Egyptian is acting in service to the French invaders. The prevailing French narrative of conquest is supported by such encounters between East and West.

![Fig. 29 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-29.jpg)

Fig. 29 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 30 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 14. Vol. II, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Though presented as a complete and unified work, the Description is the creation many groups of authors, savants, and engravers alike, over a period of decades and separated by thousands of miles. The network of print workshops struggled with the challenge of depicting hundreds of ancient Egyptian monuments in a medium designed to convey traditional Western architecture to a European public wholly unfamiliar with such non-Western styles and principles. The awesome scope of the project inevitably resulted in accuracies and interpretive license. Yet, these images continue to influence study of ancient Egypt in both their print and digital forms. The Description is a testament to a historiographic moment in the development of Egyptology and a massive artistic and logistical accomplishment. The legacy of the Description de l’Égypte endures, as its images continue to spark delight and inspire awe.

Endnotes

[i] Michael Albin, “Napoleon’s Description de L’Egypte: Problems of Corporate Authorship.” Publishing History 8 (January 1, 1980), 65–85.

[ii] David Prochaska, “Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description de l’Égypte (1809–1828).” L’Esprit Créateur 34, no. 2 (1994), 69–91.

[iii] Anne Godlewska, “Map, Text and Image. The Mentality of Enlightened Conquerors: A New Look at the Description de l’Egypte.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 20, no. 1 (1995), 5.

[iv] Godlewska, “Map, Text and Image,” 9.

[v] Henry Petroski. The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance. 1st ed. (New York: Knopf: Distributed by Random House, 1990), 70.

[vi] Richard Taws, “Conté’s Machines: Drawing, Atmosphere, Erasure,” Oxford Art Journal 39, no. 2 (August 2016), 252–254.

[vii] Ibid, 256.

[viii] Ibid, 256.

[ix] Fernand Emile Beaucour, Yves Laissus, and Chantel Orgogozo, The Discovery of Egypt (Paris: Flammarion, 1993), 140.

[x] Godlewska, “Map, Text and Image,” 11.

[xi] Ibid, 17.

[xii] Ann D’Arcy Hughes and Hebe Vernon-Morris, The Printmaking Bible: The Complete Guide to Materials and Techniques (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008), 82.

[xiii] Bamber Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical

Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet, 2nd ed (New York, N.Y: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 9b.

[xiv] Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints, 9a.

[xv] Taws, “Conté’s Machines,” 256.

[xvi] Ibid, 259.

[xvii] Beaucour et al., 146.

[xviii] Charles Coulston Gillispie, “Notes,” 2.

[xix] Rebecca Zorach, Paper Museums: The Reproductive Print in Europe, 1500–1800. (Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2005), 16.

[xx] Linda Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” in The Politics of Vision: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Art and Society (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 38.

[xxi] Ibid, 22.

[xxii] Prochaska, The Pencil, 84.

Author Bio:

Katherine Parks is a book conservator in New York. She was the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Library & Archive Conservation at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University where she received her MA in Art History and MS in Conservation in 2020. She has held positions at the Library of Congress, Columbia University Libraries, and will be joining Cornell University Library as the Conservator for Rare and Distinctive Collections in the fall of 2021.