Isabela Muci Barradas

Princeton University

Abstract

In May of 1927, Mário de Andrade embarked on a three-month journey from São Paulo to the Amazon and back. Part travelogue, ethnographic assemblage, and literary compilation, the manuscript that emerged from the trip—comically titled The Apprentice Tourist—is as difficult to classify as the more than 500 similarly elusive photographs that Andrade took during his Amazonian journey.

This paper embraces performance scholar Diana Taylor’s appeal to rethink critical methods of analysis by framing Andrade’s travel diary and photographs from his trip to the Amazon as part of a repertoire of embodied practices. It proposes to see Andrade’s The Apprentice Tourist and the corresponding photographs as setting the stage for a scenario of encounter, while simultaneously aiming to disrupt these types of scenarios through satire and fiction. Far from a detached observer, in each scenario Andrade becomes an implicated actor—one who encourages multiple performative repositionings—and implicates viewers in the process. The paper analyzes a selection of images from Andrade’s trip examining how they unsettle photography’s documentary mode.

![]()

Turista desgeograficado: Mário de Andrade’s Photographs

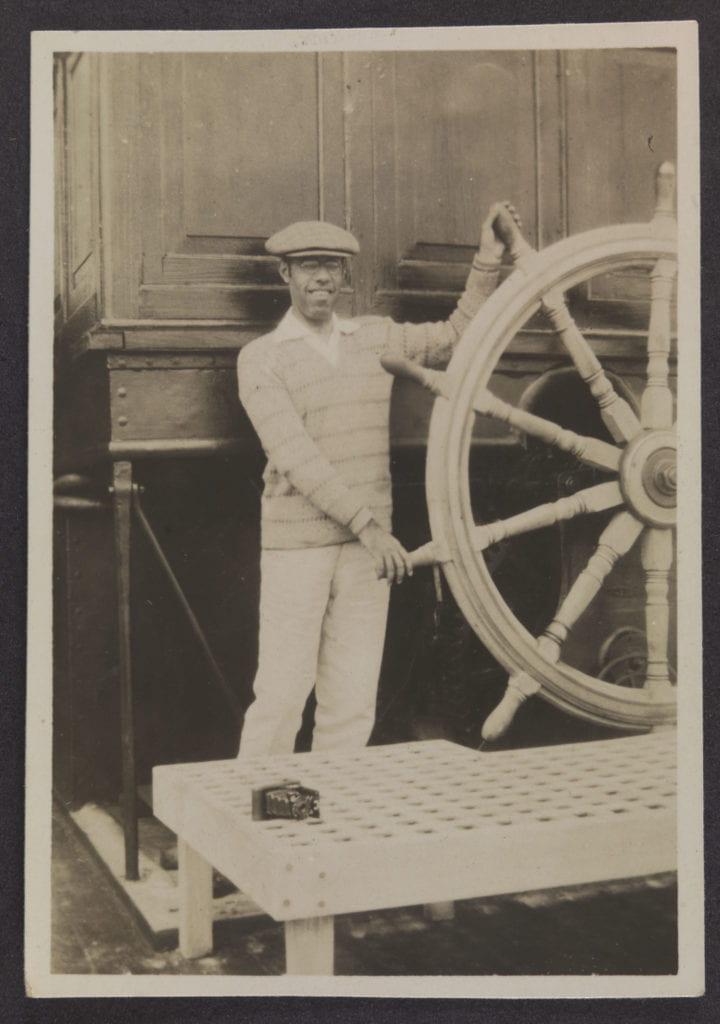

A fashionable tourist on board of the São Salvador smiles for the camera with the boat’s steering wheel in hand (fig. 1). As if to foreground this photographic event, he poses with his “Codaque” propped up in front of him.[1] Taken in June of 1927, the image pertains to a different type of photographic steerage, one of multiple haphazard effects characteristic of the untidy realm of snapshot photography. The tourist in question is Brazilian modernist poet, writer, critic, musicologist, and performer of numerous creative roles, Mário de Andrade (1893–1945). In May of 1927 Andrade decided to embark on a three-month journey from São Paulo to the Amazon and back, traveling across the northeastern coast of Brazil, the Amazon, Madeira, and Solimões rivers, as well as the Amazonian regions of Bolivia and Peru. Unlike his modernist peers—including artist Tarsila do Amaral and her husband, poet Oswald de Andrade, who spent considerable time in Europe—Andrade never travelled extensively overseas.

Fig. 1 Mário de Andrade, “Bordo do São Salvador I / junho, 1927” [On board of the São Salvador I /June, 1927], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo.

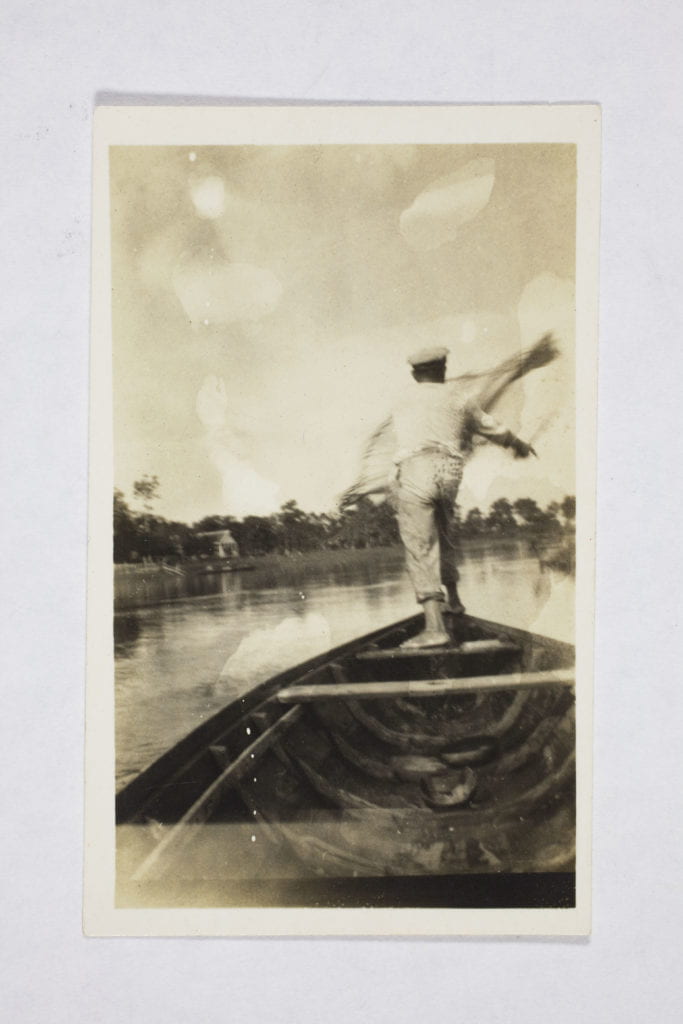

Fig. 2 Mário de Andrade, “Futurismo Pingando, 7 junho, 1927” [Dripping Futurism, June 7, 1927], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo.

Wishing to decenter the historic role of writing as a distinctive feature of the archive (i.e., “writing = memory/knowledge”), Diana Taylor foregrounds the possibilities of performance in order to consider how a repertoire of embodied practices can be conceived as “an important system of knowing and transmitting knowledge.”[5] Hence, Taylor calls for the recognition of both the materiality of the archive and its repertoire of embodied practices. If the record-keeping of the archive and the ephemeral “choreographies of meaning” from the repertoire can be held together, it is to weaken the idea that embodied actions fall outside the realm of memory.[6] As such, Taylor places the focus on epistemic and mnemonic systems that prioritize lived experience in an effort to “free ourselves from the dominance of text” and, in doing so, rethink critical methods of analysis.[7] For instance, insisting on taking the repertoire seriously, Taylor extends an invitation to look closely at scenarios as paradigms for “understanding social structures and behaviors.”[8] Analogously, I propose to see Andrade’s The Apprentice Tourist and corresponding photographs as setting the stage for a scenario of encounter, while simultaneously aiming to disrupt the power dynamics these scenarios facilitate through satire and fiction.

This paper embraces Taylor’s appeal to rethink critical methods of analysis by focusing on Andrade’s travel diary and photographs from the point of view of the repertoire. Even when these two types of documents (travel photographs and journal entries) would typically pertain to the realm of the archival in their conventional record-keeping qualities— especially as material evidence of the colonial legacies that similar dynamics of encounter have enabled—Andrade’s satiric embodiment of colonial posturing undermines their documentary valence and provides instead the fictional scenario of an apprentice tourist. More broadly, this is a scenario that denaturalizes the hegemonic power structures shaping early travel and survey photography, often rendered visually through devices that include framing, posing, costuming, or vantage point.

Far from a detached observer, Andrade becomes an implicated actor, one who encourages multiple performative repositionings while implicating the viewer. Considering his tourist persona, such repositionings allow for imaginative geographies to flourish. In fact, Andrade would expand such experimental geographic approaches after his Amazonian trip. In the second preface to his pivotal novel Macunaíma (1928), he introduces the neologism “desgeograficar” [“degeographize”] without providing a clear definition.[9] Similarly to the strategies of recombination that he used in writing Macunaíma, I propose desgeograficar can be understood as a tactic for unlearning actual geographic principles. Largely undertheorized, the concept serves well for the purposes of analyzing Andrade’s photographic outcome of his Amazonian trip, as it rejects essentializing a region and instead favors indeterminacy.

Following the methods of what I call the “turista desgeograficado” [“degeographized tourist”], the four sections that comprise this paper serve more as performative snapshots of Andrade’s trip than as a linear account of his journey. The first section examines one of the main contradictions in Andrade’s project: the need to “discover” Brazil while trying to foreground his role as apprentice tourist through what Esther Gabara has described as a constant process of erring where the unfinished (rather than the polished) becomes an ethical stance more than an aesthetic choice. Gabara’s work is foundational to this paper for its understanding of Andrade’s images as simultaneously local and out of place.[10] Andrade’s contradictions are further analyzed in the second and third sections, beginning by contextualizing his work within Brazil’s larger modernist movement and subsequently analyzing a series of his self-portraits from the trip. The final section focuses on the larger implications of Andrade’s degeographizing strategies.

As such, an analysis of a series of photographs from Andrade’s 1927 trip, along with selected entries from his travel diary, elucidate how he unsettles photography’s documentary mode by creating a performative scenario. Indeed, Andrade’s juxtaposition of embodied practices and fictional modes points to the limits of documentary accounts. Moreover, in emphasizing his role as an apprentice tourist while traveling largely within Brazil, Andrade challenges the fixity of concepts such as “native” by calling attention to the colonial underpinnings of his own actions. The result is both the recognition of the violence embedded in the process of enabling such scenarios of encounter, as well as a call to learn how to see Brazil on its own terms. In the process, Andrade traces a degeographized cartography, one that emphasizes the political and ethical valences of tourist pictures through the creation of dissonant scenarios. Andrade’s repurposing of what a tourist picture can do ultimately comprises an invitation, borrowing Ariella Azoulay’s terms, to unlearn the origins of photography.[11]

(Un)Learning how to see: Abrolhos

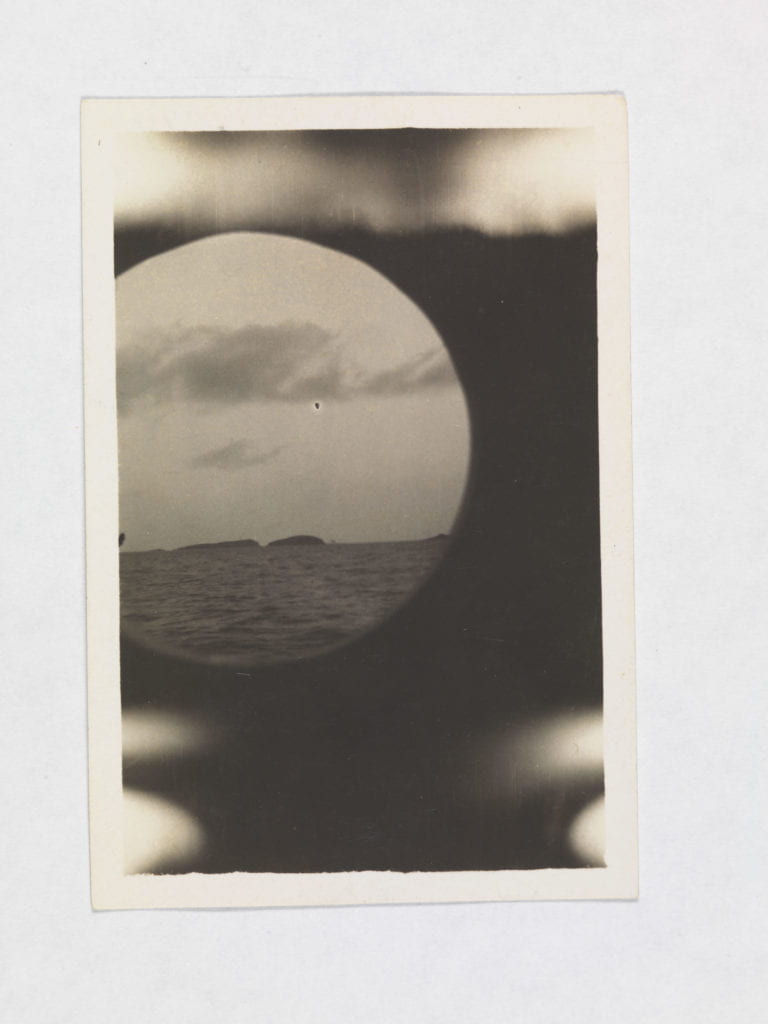

Setting the scene, the first image recorded from Andrade’s trip is titled Abrolhos (fig. 3). The center of the image is prominently shaped in the form of a circle; that is, an off-centered, cut-off circle pointing to a cropped horizon line. Most likely it was made by placing the camera in front of a boat’s window, or perhaps on one end of a viewing device—a spyglass or telescope. A small group of floating islands can be discerned towards the center, the Abrolhos archipelago located on the coast of the state of Bahia. Abrolhos is a noteworthy point of entrance into the apprentice tourist’s world. Right from the start, Andrade implicates spectators by making them look out to the sea, as if already traveling. At the same time, by choosing this particular circular framing, he decides to conceal more than half of the seascape.

Fig. 3 Mário de Andrade, “Abrolhos, 13 de maio, 1927” [Abrolhos, May 13, 1927], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo.

The circularity of the frame in Abrolhos resembles the shape of the prints produced by George Eastman’s 1888 Kodak No. 1 camera. As one of the first cameras marketed for a wide range of audiences, the rounded images taken with a Kodak No. 1 mostly pertained to the realm of amateur photography.[12] Andrade, who was not trained as a photographer, fits the category of amateur well. That said, even when he developed an intuitive relationship with the medium, he was familiar with the trends of the European avant-garde in photography at the time—for instance, he had a subscription to the Berlin-based illustrated magazine Der Querschnitt.[13]

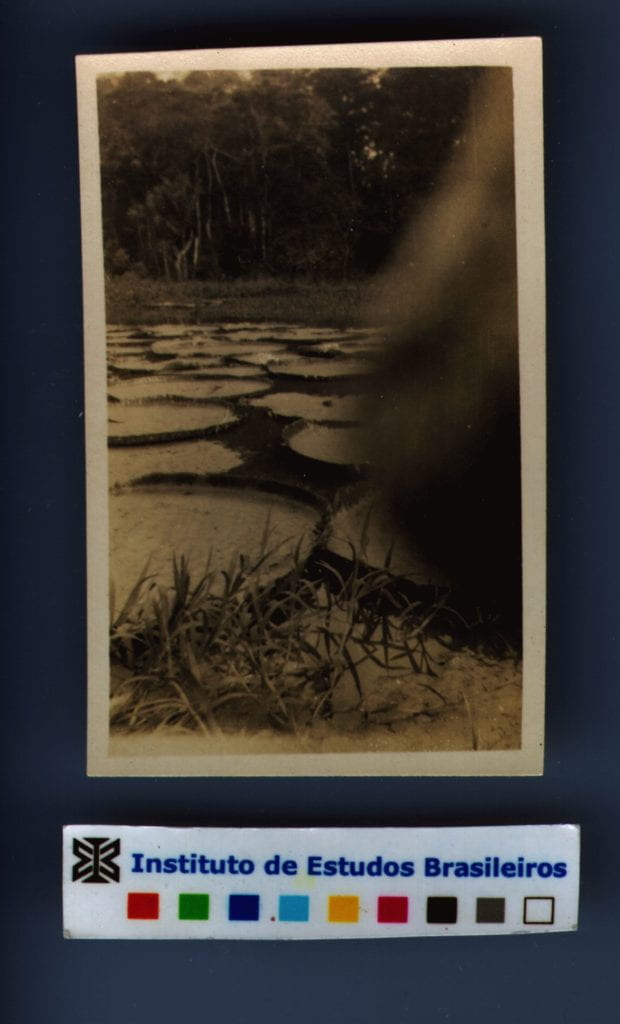

Fig. 4 Mário de Andrade, “Meu dedo bancando vitória-régia, Arredores de Manaus/ Lagoa do Amanium, 7 junho, 1927” [My finger playing Victoria-regia, Manaus/ Amanium lagoon, June 7, 1927], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo.

Fig. 5 Mário de Andrade, “Entrada dum paraná ou paranã/ 5 julho, 1927/ rio Madeira/ Ilha de Manicoré/ O I é o Madeira, o II é o rio Mataurá/ Entre duas águas” [Entry of an inlet/ July 5, 1927/ Madeira River, Island of Manicoré/ I is the Madeira, II is the Mataurá river/ Between two streams], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo.

Overall, the whole photographic archive stayed largely out of public view long after its assembly. This concealment, similar to the darkened spaces in Abrolhos, matches in intention the introductory warning note from Andrade’s travel journal. As Andrade tells us in the preface to the Apprentice Tourist manuscript, almost all the notes he took during the trip were written “without any intentions of [conceiving] a masterpiece” and “with the least of intentions in making known to others the land traveled.”[16] This remark contextualizes why the majority of the pictorial space in Abrolhos is submerged into a play of shadows. If, as Taylor proposes, the first step in reactivating a scenario is to “conjure up the physical location,” the strategies of display in Andrade’s photograph simultaneously set up a scene and negate it by obscuring it.[17]

The incongruity of not wanting to showcase the land travelled, but still taking 540 photographs along the way, is played out in the images by way of performative shadows, obstructions, superimpositions, and other mechanisms. Andrade deploys these methods to acknowledge both the colonial underpinnings of being a traveling tourist and the need to conceal the land with a veil of fiction, as if to protect it. As mentioned previously, this is the key contradiction in Andrade’s project: the need to “discover” Brazil while remaining an apprentice tourist. Perhaps this is why the Abrolhos’ mode of viewing is off-centered: it is an invitation to unlearn, or degeographize, colonial scenarios of encounter after having spotted them up close.

Modernismo Out-of-Place

Among the first generation of intellectuals to react against the Brazilian academy, Andrade is one of the key actors of the modernist movement in Brazil during the 1920s and 30s. As he recalls: “Modernism in Brazil was a rupture, it was an abandonment of principles and consequential techniques, it was a revolt against what the nation’s thinking was then.”[18] More broadly, the Brazilian modernist movement was influential throughout Latin America for conceiving a mode of critical cultural production that aimed not to be derivative. A fundamental episode in the chronology of Brazilian modernismo is the emergence of antropofagia [anthropophagy], which has been typically defined as a creative strategy deploying the myth of racial contact in Brazil to shape an autonomous identity.[19] Not fully able to escape the conundrums of primitivism, antropofagia exemplified modernismo’s main contradiction: it wanted to liberate itself from a colonial heritage by appropriating and projecting itself onto popular Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous forms (opposing European fads), while also aiming to achieve a cosmopolitan appeal (where European avant-gardes played an influential role). As such, antropofagia was underpinned by coloniality, starting with its lack of engagement with the actual realities of the groups it supposedly championed.

With the appearance of Tarsila’s Abaporu (1928) and Oswald’s Manifesto Antropófago (1928), the year 1928 was foundational for the development of antropofagia. It was precisely in 1928 when Andrade published his novel Macunaíma.[20] Known as the main anthropophagic novel of its time, it tells the story of a Brazilian “hero with no character” as he travels throughout the country in search of his muiraquitã, a carved, caiman-shaped amulet.[21] Incidentally, Andrade had written the first draft of the book right before his trip as an apprentice tourist to the Amazon, and the trip itself helped shape the novel’s final version. However, pre-dating the Manifesto Antropófago, Andrade’s photographs and text can only be read as anthropophagic before the fact. That is, as embracing a different type of antropofagia: one in which the tourist, as we are about to see, swallows his peers. While the destructive spirit that sparked modernismo is certainly present in Andrade’s photographs and texts, these do not map neatly onto Oswald or Tarsila’s anthropophagic principles. In fact, Andrade was critical of antropofagia’s primitivist undertones to the point of lamenting that Macunaíma was associated with the movement.[22] As Gabara proposes in addressing Andrade’s critical stance towards Brazilian primitivism, “Mário rejects the discovery of primitive Brazil, by the French and the Portuguese as much as by Brazilians themselves.”[23] Indeed, Andrade maintained some distance from his peers’ views in his own comical ways.

This is part of the context in which Andrade’s relatively scant photographic work came to be considered one of the first modernist manifestations of photography in Brazil. To be sure, his critical positioning within modernism underlies his persona as apprentice tourist. Towards the end of the trip, Andrade has the following journal entry: “August 11. There was no August 11 in 1927.” However, to this day four photographs survive dated “August 11,” three of which depict Tarsila and Oswald (or Tarsiwald, as Andrade would call them) on board of the Baependi. In one of the images Tarsila stands towards the left, her eyes covered in the shadow of her hat. As if squeezed by Oswald’s gigantic body, her right arm is cropped. Oswald stands in the center with a hand on his hips, sporting an oversized jacket, bulky pants, and a grim facial expression. This is not Tarsiwald’s best picture, to say the least. In addition, the photograph’s caption only indicates that these characters are on a boat, but it does not name each individual directly. It is not merely that Andrade omitted Tarsila and Oswald from his diary entry of August 11; he preferred to eliminate August 11 from the year of 1927 altogether, while also transforming the celebrity couple into unidentified characters.

Considering that the photograph was taken on a day that did not “exist” and onboard a boat, a heterotopic space par excellence, this picture is both out-of-time and out-of-place. If a scenario, as Taylor points, “requires us to wrestle with the social construction of bodies in particular contexts,” the apprentice tourist effectively managed to degeographize the functions that Tarsila and Oswald, as key actors of Brazilian modernism, are set to perform.[24] By strategically repositioning his characters, Andrade introduces the possibility of indeterminacy within scenarios of encounter. In a gesture that unsettles documentary photography’s presumed facticity and foregrounds instead a performative scenario, Andrade makes evident that “all photographs have been taken out of a continuity” and thus are always ambiguous, to use John Berger’s terms.[25] Perhaps in prioritizing the shock of discontinuity, Andrade also invites viewers to un-see these photographs, an act of negation that functions as an ode to the modernist contradictions that Tarsiwald as a couple represent.

Performing Scenarios of Encounter

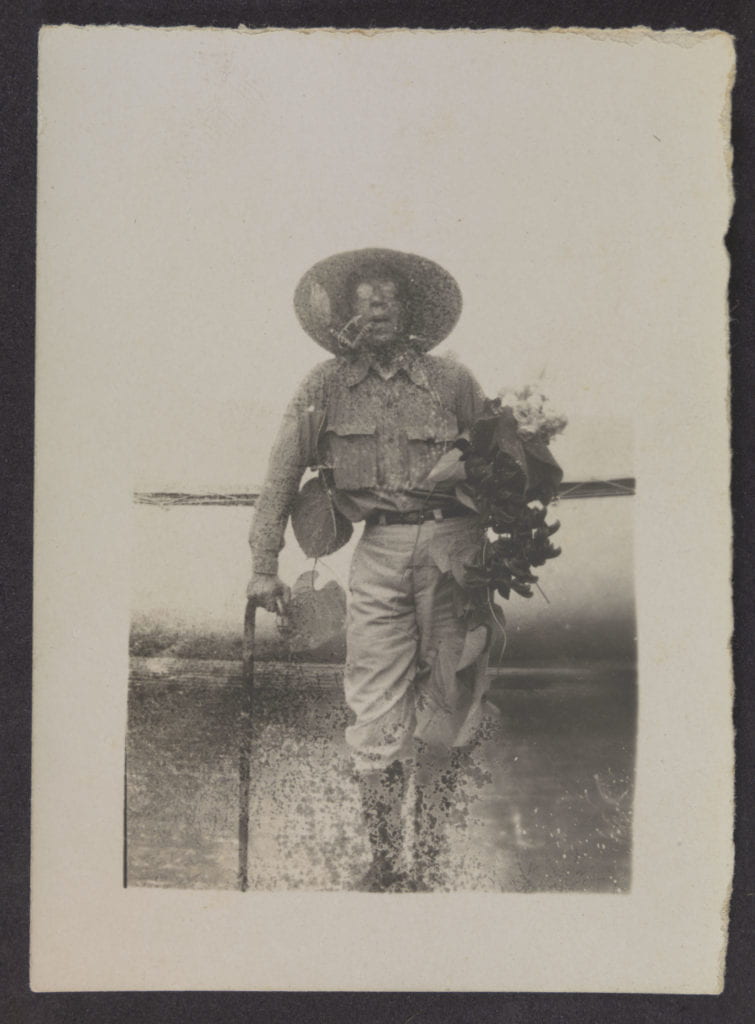

Andrade constantly repositions characters, including himself, within his tragicomic scenarios. In the case of his apprentice tourist persona, this is most obvious in the large number of self-portraits from his trip. In addressing the repositionings of characters within scenarios, Taylor suggests that “the frictions between plot and character (on the level of narrative) and embodiment (social actors) make for some of the most remarkable instances of parody and resistance in performance traditions in the Americas.”[26] It is the weight given to embodiment in Andrade’s self-portraits, particularly through costuming and posing, that allows for something more than cultural essentialism to be at play. If Taylor proposes that scenarios do not need to be primarily mimetic, that they usually work within a framework of reactivation and not duplication, then in Andrade’s scenarios there is room for reversals and repositionings.[27] This is not to suggest that Andrade’s endeavor lacks problematic images; in fact, the project is filled with unresolvable contradictions. The idea is to acknowledge the complexity and the layered operations at play in Andrade’s performative scenarios of encounter and the way Andrade’s controversial takes implicate “us”—his viewers—in the ethics of such repositionings.

Fig. 6 Mário de Andrade, “Eu voltando do passeio por Assacaio, 17 junho, 1927, Monstro á mostra” [Returning from taking a stroll in Assacaio, June 17, 1927, Monster on display], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo (Recto and Verso).

![Fig. 7 Mário de Andrade, “Eu tomado de acesso de heroísmo... peruano, 21 junho, 1927, Neptuno” [Taken by an outburst of [Peruvian] heroism, June 21, 1927, Neptune], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo (Recto and Verso).](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/7.Eu-tomado-de-acesso-de-heroismo-727x1024.jpg)

Fig. 7 Mário de Andrade, “Eu tomado de acesso de heroísmo… peruano, 21 junho, 1927, Neptuno” [Taken by an outburst of [Peruvian] heroism, June 21, 1927, Neptune], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo (Recto and Verso).

Fig. 8 Mário de Andrade, “Aposta de ridículo em Tefé, 12 junho de 1927” [Ridiculous bet in Tefé, June 12, 1927], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo (Recto and Verso).

While it is highly relevant that Andrade “includes himself as both subject and object,” his contradictory images stem more from a satiric acting out than any strict documentary impulse. As anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro reminds us, no one is born an “anthropologist” and even less a “native.” As he points out: “The problem is thus not that of seeing the native as an object, and the solution is not to render him a subject. There is no question that the native is a subject; but what the native forces the anthropologist to do is, precisely, to put into question what a subject can be.”[30] This is one of the main questions raised throughout the Apprentice Tourist and its corresponding photographs, where Andrade’s self-portraits can be read as unsettling documentary facticity of what has historically been considered a subject in such travels by way of shifting scenarios. Andrade is clearly not “native,” and in enacting for the camera a colonial fantasy that historically has led to genocide, the political nature of the term becomes legible.

Therefore, Andrade’s overall use of satire does not disregard the violence embedded in the process of enabling such scenarios of encounter. A clear example of Andrade’s awareness of the colonial violence at play in his scenarios comes in the form of a short story titled Caso pançudo [The Potbelly Case] written as a diary entry dated May 31st, 1927. The entry recounts a (perhaps fictive, perhaps actual) event that took place in the Amazonian town of Santarém, where a North American commission was considering settling with the aim of commercializing caucho rubber—a reference to the Amazon rubber boom (extending roughly from 1850–1920). As Andrade narrates, in order to see if the territory was suitable for relocation, the North Americans started photographing all the strong men in the town to compile a record that justified the place as an appropriate site for environmental and human exploitation.

There was a family in the town whose two sons where the utmost expression of local beauty. Alas, they were not barrigudinhos—they did not have a protuberant belly. The father was filled with pride in knowing that the North Americans wanted to photograph his sons. He allowed them to be photographed, but decided to hide inside his hammock while their picture was taken. Afraid that, notwithstanding his precaution, the photograph might have “taken him too,” the father got depressed and died of sadness soon after.[31] This is a tragicomic tale that acknowledges the violence involved in the event of photography as it intersects with patriotism, foreign extraction, and embodiment.[32] The story makes evident some of Andrade’s awareness of photography’s colonial histories. As with Viveiros de Castro, Andrade’s accounts reopen the question of who the subject of a photograph is in an extended sense by putting into question what a subject can be in the first place. In other words, if Andrade encourages us to learn how to see Brazil on its own terms, he does so by placing colonial violence at the fore and implicating himself, and his audience, into open-ended scenarios of disidentification.[33]

Cartographies: A Process of Degeographizing

What is Andrade hoping for when creating these scenarios? Unlike most early travelers, rather than “discovering” the Amazon, I propose that the main consequence of Andrade’s constant repurposing of his tourist persona is the creation of a distinct type of cartography. Suely Rolnik’s differentiation between the workings of a map and the mechanisms of cartography serves to elucidate this point: “For the geographers, cartography—differently from maps, the representation of an static totality—is a drawing that accompanies and is made at the same time as the movements of transformation of the landscape.”[34] Rolnik offers a type of cartography that addresses psychosocial landscapes and contemporary affects, one that “accompanies and is at the same time produced by the dismantling of certain worlds—their loss of sense—and the formation of others: worlds that are created to express contemporary affects, in relation to which present universes become obsolete.”[35] What defines a cartographer under these terms is a sensibility whose sole guiding rule is that, no matter the strategies used, it should always be deployed on behalf of expanding life.[36]

As it becomes apparent, Rolnik’s emphasis on cultural forms that unsettle actual maps resonates with Andrade’s conception of desgeograficar. Indeed, Andrade’s images reject the dogmatic totality underlying the logic of maps, along with the violent colonial worlds these instruments have historically enabled. As we have seen, Andrade was aware of the double-edged role that photography as a technology played (and continues to play) in the shaping of worlds.[37] But differently from the colonial impulse that enabled photography to forcefully create new imperial worlds, Andrade’s scenarios are fictionally dissonant—they do not allow for a clear “mapping.” This is why Andrade’s specific choice of the tourist persona becomes crucial. As Jonas Larsen suggests, “the ‘nature’ of tourist photography is a complex ‘theatrical’ one of corporeal, expressive actors; scripts and choreographies; staged and enacted ‘imaginative geographies.’”[38] Paired with Andrade’s degeographizing strategies of not showing a single essentializing “locality,” tourist photography, in this case, becomes a stage for the creation of open scenarios that reimagine a geographical space.

Fig. 9, Mário de Andrade, “Rio Madeira / Retrato da minha sombra trepada na tolda do Victoria, julho 1927/ Que-dê o poeta?” [Madeira River/ Portrait of my shadow from the top of the Victoria, July 1927/ Where’s the poet?], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo.

Fig. 9.1A/B, Mário de Andrade, “Rio Madeira / Retrato da minha sombra trepada na tolda do Victoria, julho 1927/ Que-dê o poeta?” [Madeira River/ Portrait of my shadow from the top of the Victoria, July 1927/ Where’s the poet?], Arquivo Mário de Andrade, Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – IEB-USP, São Paulo. (Image enlargement on postcard paper on the lower left and back of enlargement on the lower right)

Endnotes

[1] The word “Codaque” is the nickname Mário de Andrade gave to his small Kodak camera.

[2] It was Andrade who comically called Guedes Penteado the “Coffee Queen,” given that her family’s fortune was made through the commercialization of coffee. In Portuguese, the manuscript’s title is the following: O Turista Aprendiz/ viagens pelo Amazonas até/ o Peru, pelo Madeira até a Bolívia/ e por Marajó até dizer chega—1927.

[3] Telê Ancona Lopez suggests that Andrade is mocking one of the grand travels recorded in his family history. Andrade’s grandfather, politician and jurist Joaquim de Almeida Leite Moraes, had a travel diary- turned-book titled Apontamentos de viajem de São Paulo á capital de Goyaz, desta á do Pará, pelos rios Araguaya e Tocantins e do Pará á Corte: Considerações Administrativas e Políticas [Travel notes from São Paulo to Goyaz’s capital, from there to that of Pará, along the Araguaya and Tocantins rivers and from Pará to Corte: Administrative and Political Considerations]. See: Telê Ancona Lopez, “O Turista Aprendiz na Amazônia: a invenção no texto e na imagem,” Anais do Museu Paulista 13, no. 2 (2005): 139.

[4] Luciana Martins, Photography and Documentary Film in the Making of Modern Brazil (Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press, 2013), 133.

[5] Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 24 and 26.

[6] Ibid, 20.

[7] Ibid, 27.

[8] Ibid, 29. An important precedent for analyzing Andrade’s trip through the lens of the repertoire, Taylor devotes the second chapter of her book, titled “Scenarios of Discovery,” to analyzing the relations between performance and ethnography.

[9] Lopez, “O Turista Aprendiz na Amazônia,” 140. See also: Fernando Rosenberg, The Avant-Garde and Geopolitics in Latin America (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006), 43.

[10] In her book Errant Modernism: The Ethos of Photography in Mexico and Brazil, one of the most in-depth accounts of Andrade’s photographic work, Gabara suggests that Andrade made photography err. As she notes: “In a Brazilian modernist ethos everything must be ‘errado,’ which means that it is both local and out of place, ethically engaged but judged to be wrong, and, finally, abstract but referential.” See: Esther Gabara, Errant Modernism: The Ethos of Photography in Mexico and Brazil (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 37.

[11]Ariella Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London; New York: Verso, 2019), 2-3. Azoulay develops her ideas on the topic in her book Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism where she invites readers to imagine that the origins of photography can be traced back to 1492. As she asks: “What could this mean? To answer this question we have to unlearn the expert knowledge that calls upon us to account for photography as having its own origins, histories, practices, or futures and to explore it as part of the imperial world in which it emerged. We have to unlearn its seemingly obvious ties to previous and future modes of producing images and to problematize these ties that reduce photography to its products, its products to their visuality, and its scholars to specialists of images oblivious to the constitutive role of imperialism’s major mechanism – the shutter. Unlearning photography as a field apart means first and foremost foregrounding the regime of imperial rights that made its emergence possible.”

[12] By the 1920s amateur photography was widespread in Brazil. Andrade’s camera, however, was a small format Kodak Model B Autographic Vest Pocket. These cameras were made between 1923-1935 and were known for enabling the photographer to record, at the moment of taking the picture, key information such as time of exposure or date (thus the name Autographic). For a detailed account of Andrade’s camera workings see: Viviane Azevedo Vilela, Mário de Andrade fotógrafo: possibilidades de una câmera moderna (São Paulo: Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, USP, 2017), 8.

[13] Andrade also had access to the following publications: L’Esprit Nouveau from Paris, Der Sturm from Berlin, and Europe: revue littéraire mensuelle from Paris. With regard to Der Querschnitt (which featured the work of photographers such as Man Ray), Andrade subscribed to it from 1924 to 1931, years in which he was most actively photographing. For an in-depth study on Der Querschnitt’s impact on Andrade’s photographic training, see: Azevedo Vilela, Mário de Andrade fotógrafo, 11.

[14] Mário de Andrade, O turista aprendiz (Brasília: IPHAN, 2015), 115, 159.

[15] One of Andrade’s contributions was to foreground the importance of colloquial language. He even created his own “gramatiquinha” [little grammar book]. See: Edith Pimentel Pinto, A Gramatiquinha de Mário de Andrade: Texto e Contexto (São Paulo: Livraria Duas Cidades, 1990).

[16] Andrade, O turista aprendiz, 48. Translated from Portuguese by author.

[17] Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire, 29.

[18] Mário de Andrade and Richard Correll (trans.), “The Modernist Movement,” Portuguese Studies 24, no. 1 (2008): 98.

[19] It was Oswald and Tarsila who proposed anthropophagy as a Brazilian mode of cultural cannibalism. In its transcultural sense, anthropophagy emerged with Oswald’s 1928 Manifesto Antropófago, written in response to Tarsila’s painting Abaporu, also from 1928. Referencing how the Tupi Indigenous populations would ritualistically eat their enemies to incorporate what they valued from them, antropofagia encouraged building a transcultural mode of cultural production that incorporated both “imported” avant-garde schemes and local traditions, including those from colonial times.

[20] The first chapter of Macunaíma was published in the second issue of the Revista de Antropofagia.

[21] Mário de Andrade, Macunaíma (New York: Random House, 1984), 130.

[22] See Kimberle S. López, “Modernismo and the Ambivalence of the Postcolonial Experience: Cannibalism, Primitivism, and Exoticism in Mário De Andrade’s ‘Macunaíma,’” Luso-Brazilian Review 35, no. 1 (1998): 28-29.

[23] Gabara, Errant Modernism, 78.

[24] Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire, 29.

[25] John Berger and Jean Mohr, Another Way of Telling (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 91.

[26] Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire, 30.

[27] Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire, 32.

[28] Gabara, Errant Modernism, 82.

[29] Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), 9.

[30] Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “The Relative Native,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3, no. 3 (2013): 479.

[31] Andrade, O turista aprendiz, 88.

[32] Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (London; New York: Verso, 2010), 26. In addressing the moment before, during, and after the act of photographing, Andrade’s account presents an extended understanding of the act of photographing, or what Azoulay has theorizes as “the event of photography.”

[33] José Esteban Muñoz, “Performing Disidentifications” in Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 11-12. As José Esteban Muñoz has defined the term, disidentification is a “mode dealing with dominant ideology, one that neither opts to assimilate within a structure nor strictly opposes it; rather, disidentification is a strategy that works on and against dominant ideology. Instead of buckling under the pressures of dominant ideology (identification, assimilation) or attempting to break free of its inescapable sphere (counteridentification, utopianism), this ‘working on and against’ is a strategy that tries to transform a cultural logic from within, always laboring to enact permanent structural change while at the same time valuing the importance of local or everyday struggles of resistance.”

[34] Suely Rolnik, Cartografia sentimental: transformações contemporâneas do desejo (São Paulo: Estação Liberrade, 1989), 15. Translations from Portuguese by author unless otherwise noted.

[35] Rolnik, Cartografia sentimental, 15.

[36] Ibid, 70.

[37] Azoulay, Potential History, 5. As Azoulay notes: “When photography emerged, it didn’t halt this process of plunder that made others and others’ worlds available to some, but rather accelerated it and provided further opportunities to pursue it. In this way the camera shutter developed as an imperial technology.”

[38] Jonas Larsen, “Families seen sightseeing: Performativity of tourist photography,” Space and culture 8, no. 4 (2005): 417.

Author Bio

Isabela is a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University’s Department of Art & Archeology focusing on modern and contemporary art from Latin America as well as the history of photography. Her dissertation examines photographic practices in the Amazon during the 1970s and 1980s that use experimental approaches to advance environmental and Indigenous causes. At Princeton, she is a 2021 Community College Teaching Fellow and the recipient of the 2017-18 Lassen Fellowship in Latin American Studies. Isabela holds a B.A. in the history of art and architecture, modern culture and media, and Latin American and Caribbean studies from Brown University.