Giorgia Maria Maffioli Brigatti

Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Abstract

This paper examines how the artist and the calligrapher in sixteenth and seventeenth century Iran were closely related through the expectations weighted on them by their contemporaries. Conceptions of virtues and good character were commented upon while assessing both calligraphers’ and artists’ works. On a conceptual level, the ‘theory of the two qalams’ (pens) aimed at equalizing the art of painting to the art of calligraphy. On the visual level, drawings could be executed with calligraphic lines, which can be seen in the works of renowned artists like Reżā ‘Abbāsi (c. 1565-1635) and Mu’īn Muṣavvir (active c. 1635-1697).

Moreover, both calligraphic verses and drawings began to be conceived not as parts of books but as single-sheet works of art, which were then collected and bound into albums (sing. muraqqa‘). In these albums, master librarians, or private collectors, assembled both arts into groups, collating them in dialogue with one another by juxtaposing calligraphy with drawings/paintings, but also by creating composite pages on which word and image coexisted.

In addition, theories of vision and perception (which centered on the physical act of seeing) developed by the polymaths Ibn Sīnā (980-1037, also known as Avicenna) and al-Ḥasan Ibn al-Ḥaytham (c. 965-1040, also known as Alhazen), whose writings circulated well into the seventeenth century, offer another possible viewpoint to parallel artists’ and calligraphers’ practice. Through an important sixteenth-century calligraphic treatise, it is possible to remark on how theories of perception were part of the common cultural understanding of calligraphic productions. Particularly important was the concept of ‘creative imagination’ (that is related to one’s ability to imagine), which was at the basis of the calligrapher’s creative act when producing ‘soul-ravishing’ works of art. Through contemporary treatises on the arts, a similar background is metaphorically applied to the practice of artists, thereby, theories of perception and imagination can offer new insights on the contemporary reception of both calligraphers’ and artists’ works.

![]()

Funūn-i fażā’il (Arts of excellence): Measuring Virtue in the Tracings of the Pen and the Brush

Introduction

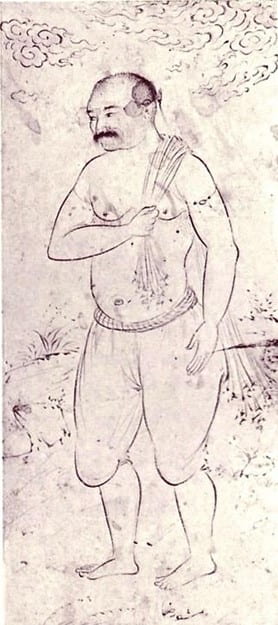

On the creamy white background of a page, black ink strokes delineate a man stripped to his waist looking to his right with a focused expression (fig. 1).[i] He is holding a scarf, slung over his shoulder, which highlights his muscular body in contrast to the soft and light fabric. This drawing, that has been titled Wrestler, is considered the ‘key’ to the period Aqa Reżā (c. 1565-1635), the renowned painter, spent away from the court, showing his interest in wrestling and the ongoing change in his style.[ii] In the artwork, the lines start to be sinuous but never break completely, showing the transition towards his more expressive use of thickening and thinning line strokes.[iii]

Fig. 1: Reżā ‘Abbāsi, Wrestler, c. 1607-1609. Black ink on cream paper, 13.7 x 6.2 cm. © L.A. Memorial Institute for Islamic Art, Jerusalem.

It is regarding this period, distanced from the Safavid court (the Safavid dynasty ruled Iran in 1501-1722), that the historian Qāżī Ahmad Qūmī (d. May-June 1606)[iv] writes: “Vicissitudes [of fate] have totally altered Aqa Reżā’s nature. The company of hapless people and libertines is spoiling his disposition.”[v] The author of the famous treatise on the arts, the Gulestān-i Hunar (Rose-garden of Art, 1596-7), is among a cohort of writers – historians, court librarians, courtiers, among others – to have indicated some of their insights into the criteria for artistic judgment in late sixteenth-century Safavid Iran.[vi] Also, the historian Iskandar Beg Munshī (1561/2-1633/4)[vii], in his chronicles on the reign of Shāh ‘Abbās I (r. 1587-1626, the fifth ruler of the Safavid dynasty)[viii], indicates how moral judgments on the character of artists and calligraphers were closely intertwined with aesthetics, writing that: “Aqa Reżā, was a skilled portrait painter, but it is well known that, in recent times, he stupidly abandoned this art in which he had so much skill and took up wrestling, forsaking his talented artist friends.”[ix] Wrestling and the company of uncouth people lacked, in the eyes of the court historian and scholar, virtues befitting the great artist and adversely, he says, induced unwelcome change in Reżā’s style.

This article will analyze the newly established importance of artists compared to calligraphers in the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-centuries in Iran. First, contemporary writings on the moral values of artists and calligraphers will be analyzed, then the similarities of the visual qualities of the lines in drawings and calligraphic pieces will be addressed, developing on the growing self-consciousness of the artist and the popularizing of the muraqqa’ (album). Finally, it will be argued that theories of perception and imagination can be lenses through which the art of painting/drawing and calligraphy are closely relatable as causes of the ‘ravishing’ of the viewer’s soul.

Persian drawings of the seventeenth century were usually executed with ink on paper; without the addition of bright colors, the idiosyncratic character of the line becomes revelatory of the artist’s expression.[x] This was analyzed as a way to show the artist’s moral character, considered by connoisseurs and collectors to be ‘visible’ through the gesture of the hand in the artworks. In treatises on art and calligraphy, contemporary writers judged both the calligrapher and the artist on their moral values, expressed in their everyday actions. That the artist’s character was subject to moral judgment is indeed a new phenomenon, at least as far as historical evidence reveals. Moral character, as a condition affecting artistic production, is the inspiration of this article as it investigates the potentiality of relating calligraphy and drawing through the analysis of the line and the movement of brush and ink on paper. This issue of morality regarding Safavid artists, were they spiritually wholesome, has never been studied in scholarship.[xi]

It was prince Sām Mīrzā’s (1517-1566), son of Shāh Ismā’īl I, in his biography of poets, the Tuḥfa-yi sāmī (Sam’s Gift, c. 1560-1561), who defined the arts of calligraphy and poetry as funūn-i fażā’il, or arts of virtue/excellence;[xii] hence the title of this article. The writer, however, also included artists in the description of cultured personalities.[xiii] I will argue that this conception of virtue, often applied to poetry and calligraphy, was also considered fitting the arts of painting, and drawing, in particular. As contemporary texts show, the artist was expected to be spiritually steadfast, as a matter of moral authority that legitimated the work of the hand; this had a direct impact on the appreciation of their artworks.

Scholarship is rich in its analysis of the arts of calligraphy and drawing but has not, as yet, considered the potential visual and conceptual links between the two. Nor have scholars drawn parallels, through an understanding of the two practices, between the figure of the calligrapher and the artist. Rather, studies center on one or the other of these arts, with few exceptions that often deal with art treatises that concern both. For example, Yves Porter discusses the ‘theory of the two qalams (pens)’ and argues that Safavid writers, drawing on an earlier literary tradition, attempted to link calligraphy and painting to give more legitimacy to the latter.[xiv] ‘Abdi Beg Shīrāzī (c. 1515-1581), a poet, historian and administrator, in his Āyn-i Iskandarī (Rules of Alexander, c. 1543) developed the ‘theory of the two qalams’ that made the art of depiction emanate directly from God; just as the art of calligraphy was considered noble because it captured His direct revelations.[xv] The two qalams (the reed pen and the hair brush) both originated from and were used by God in the creation of the world. By the seventeenth century, it is possible to claim that this theory was widespread.

Moreover, David Roxburgh in his book devoted to album prefaces, indicates that painting and allied practices of the arts of the book acquired new visibility, and contemporary writers could shape aesthetics and define canons of art through their writings.[xvi] Roxburgh, however, limits his research to album prefaces, a previously neglected category of sources, leaving behind the other more widely studied important treatises on the arts.[xvii] Qāżī Ahmad’s treatise on the arts of painting and calligraphy fell outside the boundaries of his research. In this article, I will pull together a number of these historical sources on the arts of writing and painting including Qāżī Ahmad’s treatise, to argue that the position of the artist and the calligrapher were closely related and that artists’ moral character, as much as aesthetic judgments, were often determined on shared assumptions and applied to both practices.

The calligrapher was entitled to write the Word of God, as the Qur’an was dictated to the Prophet Muhammad (c. 570- 632) directly in the Arabic language. The art of calligraphy was, and still is in some ways, the most venerated art, and the calligrapher had to be spiritually steadfast to practice it. Their moral integrity was essential to the success of their writing.[xviii] At the beginning of the sixteenth century, treatises on the life and works of calligraphers and painters started to envisage ways of comparing the two arts through the use of witty metaphors, for example comparing the album pages (both written and painted) to the ‘album of the celestial sphere’ (muraqqa’-i sipihr) created by God.[xix] These claimed that both calligraphy and painting/drawing derived their authority from the twofold potential invested in the pen created by God.

Measures of Virtue

In Islamic practice, it is understood that to become a calligrapher, both mind and spirit need to be trained to the forms of the script and the purity of heart. Adjectives used to describe calligraphy in fifteenth- to seventeenth-century texts are highly suggestive: pure/clear (sāf),[xx] solid/firm (mustahkam),[xxi] clean/pure (pākīza),[xxii] sweet/delicate (shīrīn).[xxiii] Similar adjectives are used for the calligraphers themselves. Dūst Muhammad, distinguished artist and calligrapher (active c. 1510-1564), writes of the purity (safā) and clarity (tīzī) of Mālik Daylamī’s pen (active sixteenth century)[xxiv] and that Maulānā Sultan Muhammad Nur (c. 1472-1536) was an accomplished and pure (pākīzagī) scribe, who was devoted (vara’) and pious (taqvī) in his entire life.[xxv] Qāżī Ahmad remarks that the calligrapher Sayyid Haydar “was possessed and used to be rapt with ecstasy,” while his colleague Maulānā Ma’ruf Khattāt-i Baghdādi “was a man of noble nature and complete self-control (khwīstan-dār).”[xxvi] In addition, Qāżī Ahmad quotes in his treatise a long epistle by the preeminent calligrapher Maulānā Sultān ‘Alī (d. 1520) whose ending contains specific guidance on the habits and behavior of the calligrapher.[xxvii] Among these are the ascetic life devoted to the labour of the pen, and also exhortations to eschew lies and calumny, evil practices and intrigues: “he who knows the soul, knows that purity of writing proceeds from purity of heart.”[xxviii] In this way, the heart and writing of the calligrapher are inextricably entwined.

In the seventeenth century, the morality of artists as well became a matter of debate for commentators. Iskandar Beg and Qāżī Ahmad commented that Reżā and the painter Sadiqi Beg (1533-1610), were well known for their bad temper and acrimonious character.[xxix] Qāżī Ahmad also remarks that refinement of thought and deep meditation contributed to prince Sultān Ibrāhīm-Mirzā’s (1540-1577) great success in painting and decorating;[xxx] Aqā Mirak (active c. 1520-1575) was a clever and talented painter, and a sage; and similarly, Maulānā Qadimī, a portraitist of the Royal Library (c. 1510-1560), had a dervish or humble character (abdāl).[xxxi] In the Khvāndāmīr/Amini preface, the legendary painter Behzād (c. 1450-1535) is praised as an artist: “felicitous in his works/ excellent in character, praiseworthy in his manners,” and on his moral dispositions, he says: “pure in his beliefs, traverser of the paths of love and affection.”[xxxii]

As should be expected, historians and commentators carried their own biases, at times omitting some features of the character of the artists they spoke about. For example, as Abolala Soudavar has noted, Qāżī Ahmad’s information on Behzād was drawn from Budaq Munshī’s Qazvini (active c. 1536-1549) Javāhir al-Akhbār (Jewels of Chronicles), completed in 1576-77, a couple of decades earlier than the former’s Gulestān-i Hunar.[xxxiii] Qazvini, prince Bahram Mīrzā’s (1517-1549) personal secretary, wrote that Behzād kept on drinking notwithstanding Shāh Tahmāsb’s ban against wine. Qāżī Ahmad, however, omits this side of Behzād’s character and focuses exclusively on his positive qualities and unblemished character. Instances like these undermine the reliability of writers’ judgements.[xxxiv] Nevertheless, as much as calligraphers’ works were perceived as a reflection of their own nature and personality, the artist’s character was also commented upon and discussed in similar terms.

Drawings and Calligraphic Artworks as Records of their Makers

As much as calligraphers signed their works, artists in this period signed their artworks, with increased frequency, and left personalized marks on them, ranging from a couple of lines on the conditions of the making of the work, to their dedications as gifts.

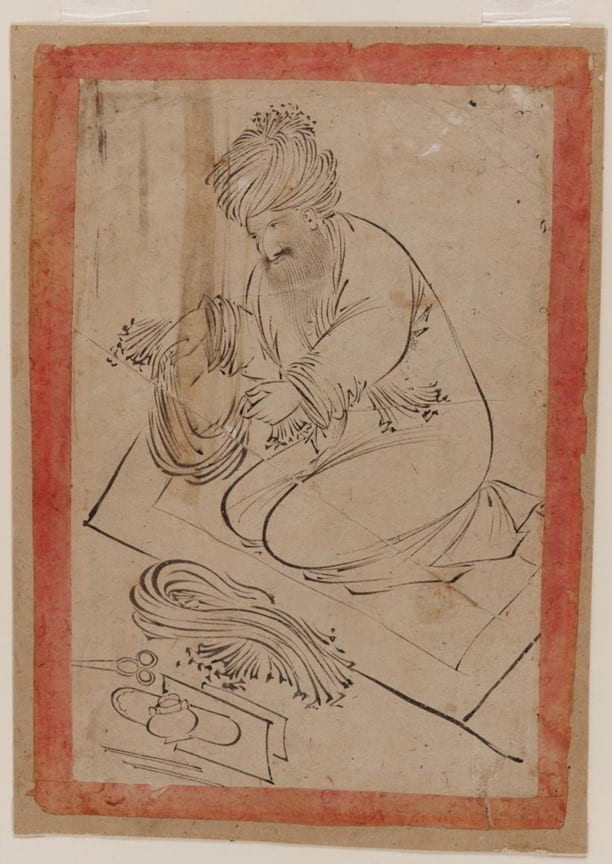

Reżā popularized the fluid calligraphic line as the norm in Safavid single-page drawings. A brilliant example of his draughtsmanship is The Cloth Merchant (fig. 2). Here the cloth is the true protagonist: it wraps dramatically around the body of the merchant, whose face is barely visible as the delicate thin lines of his beard contrast with the thick and rather plastic rendering of his turban and clothes. Similarly, his hands, thin and soft, timidly appear from under the boldly rendered sleeves and the richly wrinkled sash that he is carefully holding.

Fig. 2: Reżā ‘Abbāsi, The Cloth Merchant, mid-seventeenth century, Isfahan. Ink on paper, 171. x 11.5 cm. (The Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

This employment of the pen or brush (both identified as qalam in historical texts) creates the drawing’s texture and conveys to the viewer a sense of plasticity in a solely graphic manner. These strokes led scholars to define them as “calligraphic” due to their visual resemblance to the characteristic thickening and thinning lines of calligraphic letters.[xxxv] As Lamia Balafrej has argued for Timurid drawings, the aesthetic of the line is at the basis of both painting and calligraphy.[xxxvi] The calligraphic lines create a visual understanding of volumes rendered through graphic dexterity, particularly on the merchant’s knees and back, where the density of the lines is on the opposite spectrum of the thin and softly-rendered beard. He is holding the cloth to display it, and before him lay the implements for writing: two pens, an inkwell, paper sheets, a makta (the pen-rest used for the trimming of the pen), and scissors. These objects point to the business activities of the merchant, while hinting at the practice of the calligrapher, whose art is based on the line to form beautiful letters.

The line itself is central to both The Cloth Merchant and another anonymous drawing, Young Man Sewing (fig. 3). It depicts a youth sewing on the support of his right knee, holding the cloth with his hand. Unlike Reżā’s artwork, this drawing has been pounced for transfer, further highlighting why the lines in both drawings are so different yet central to their composition. Reżā’s gestural line displays the mastery of the great artist, while the careful and precise line of the unknown drawing reveals its use in the workshop. Little pinholes outline the figure, which were then covered in charcoal when placed onto the new surface. This way, the pounced holes would leave a mark on the new surface, without irreversibly damaging the original.[xxxvii] Tellingly, the thick calligraphic lines present a double set of pinholes, unlike the thinner outlines. This highlights the importance of the line itself, as it was not only the outline that had to be transferred, but also the particular gesture of the qalam, a point never noted by scholars.

Fig. 3: Unknown, Young Man Sewing, first half of the seventeenth century. Ink on paper, 12.4 x 7.6 cm. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.)

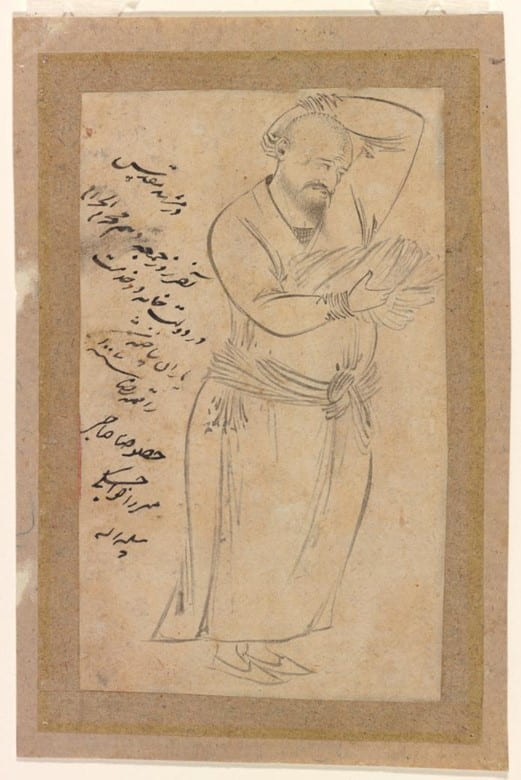

The calligraphic lines are more than just the sign of the artist’s draughtsmanship and design. Indeed, artists in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries started to leave on their artworks more insights into their personality and individual expression, mostly through written notes, alongside the signature and date. Reżā’s drawing of The Mashhad Pilgrim depicts a man who has just removed his turban to scratch his head (fig. 4). The beautifully written note by his side states: “It was made in the presence of friends in the daūlat-khāna in the holy (city of) Mashhad at the end of Friday 10th Muharram, 1007 (13th August 1598) by Reżā; especially (for) Mirza Khajeghi”.[xxxviii] The city of Mashhad is the site of the tomb of Imam Reżā (766-818), the eighth Shi’ite Imam, and numerous pilgrims travelled to the sacred site in the holy month of Muharram. Reżā made this drawing in the presence of friends naming one of them, Mirza Khajeghi.[xxxix] These details seem to point to a spontaneity of the drawing, as if completed ‘on the spot’ at the sight of this pilgrim’s discomfort. The quality of the line is also at its most heightened expressive level, particularly on the sash and the turban of the pilgrim. The nasta’līq script on the side mirrors the thickening and thinning of the lines present in the drawing as well.

Fig. 4: Reżā ‘Abbāsi, The Mashhad Pilgrim, 10th Muharram 1007/13th August 1598, Mashhad. Ink on paper, 11.7 x 7.1 cm. (The Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

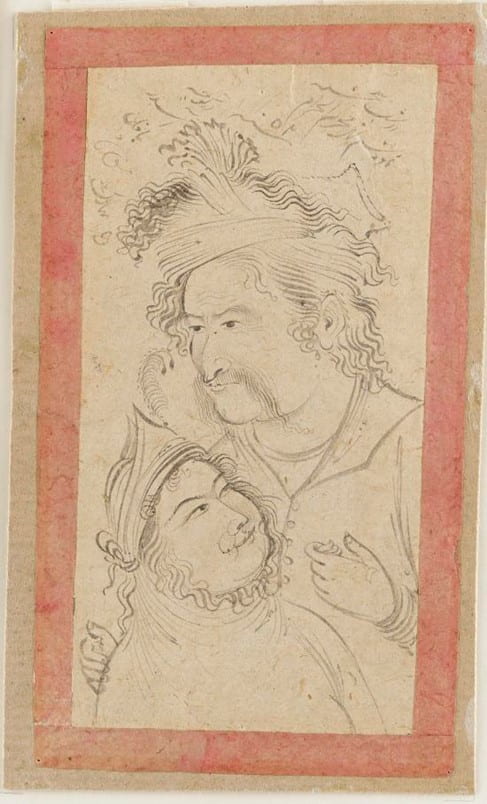

A similar play of text and image is found in Mu’īn Muṣavvir’s (active c. 1635-1697) drawing The Lovers (fig. 5). Mu’īn was Reżā’s student and implemented the style of his master’s calligraphic line. The man on the right is looking in the distance, while the woman appears to be looking lovingly towards him. The strands and curls of hair are rendered with swirling lines, deeply calligraphic in their contours, and are positioned in close proximity to the text, placed at the top of the page and around the man’s head. The text reads: “11 Muharram 1052 (9th April 1642) the composition was conceived in the lane of … weavers.”[xl] Like The Mashhad Pilgrim, this drawing was done, or at least started in an informal setting, outside the court ketabkhāna (library-cum-scriptorium). The out-of-office statement suggests that the drawing was made ‘on the spot’ when Mu’īn could capture the ‘likeness’ of the man.[xli]

Fig. 5: Mu’īn Muṣavvir, Lovers, 1642, Isfahan. Ink and colour on paper, 13.2 x 6.9 cm. (The Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

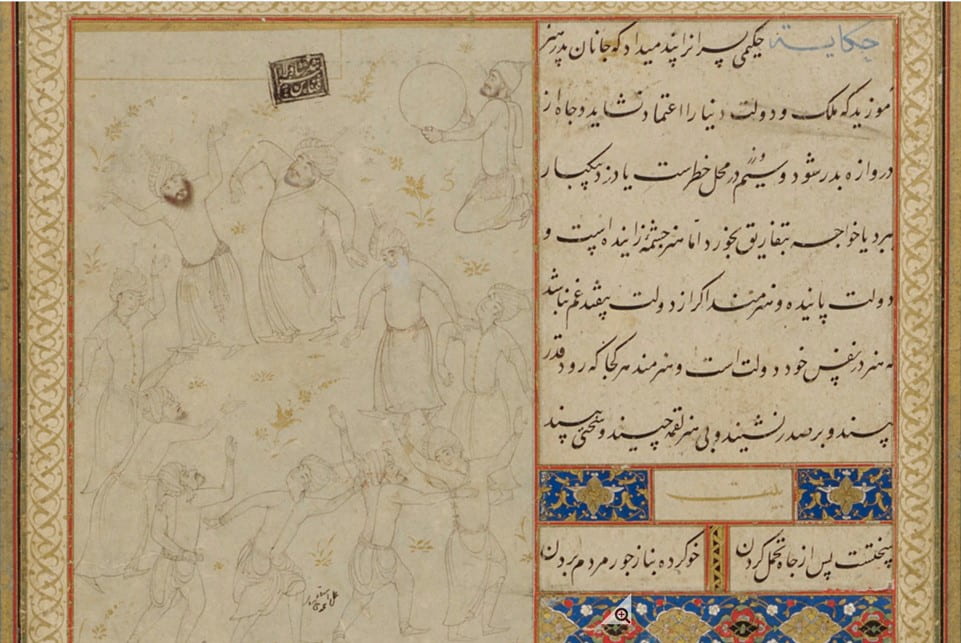

Extraordinary evidence of Mu’īn’s personal impressions on contemporary events is developed in Tiger attacking a Youth (fig. 6). In the drawing, a large tiger rests its feet on top of a man, whose face is covered by the animal’s jaws. Seven people attempt to refrain the animal, two of them rush onto the scene from an open gate on the left. The long inscription reads:

“It was Monday, the day of the Feast of the blessed Ramadan, of the year 1082, when the ambassador of Bukhara had brought a tiger with a rhinoceros as gifts for His most exalted Majesty, Shāh Suleyman. At the Darvaza-Dawlat, the above-mentioned tiger jumped up suddenly and tore off half the face of a grocer’s assistant, fifteen or sixteen years of age. And he died within the hour. We heard about the grocer but we did not see him. (This) was drawn in memory of it.”[xlii]

Fig. 6: Mu’īn Muṣavvir, Tiger attacking a Youth, 8th February 1672/ 8 Shawwal 1082, Isfahan. Ink and watercolour on paper, 14.1 x 21.1 cm. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The script further details the terrible conditions affecting Isfahan, with heavy snowfall, hunger, and lack of firewood. The personal character of this drawing offers an insight into Mu’īn’s life and work conditions, but also hints at his own personality. Furthermore, the drawing is rendered in Mu’īn’s characteristic calligraphic gesture, particularly in his depiction of the tiger, whose leg and jaws are delineated with textured lines.

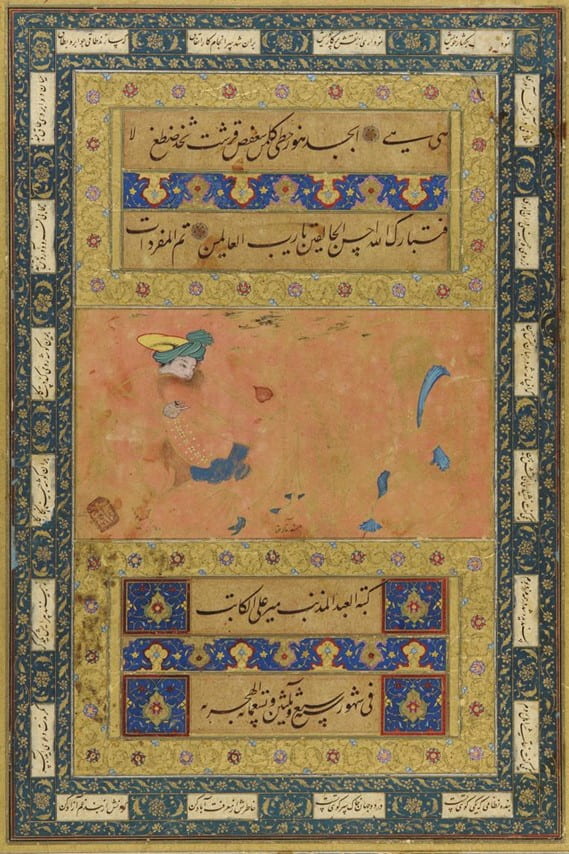

The beautifully written words in Tiger Attacking a Youth work hand-in-hand with the image and its meaning, however there are numerous examples of composite pages, in which words and image are put into dialogue by the collector or librarian who assembled the sheet. This newly reassembled relationship usually problematizes the relation between words and image as visible in Reżā’s and Mir ‘Alī al-Katib’s page (fig. 7).[xliii] Reżā’s drawing takes center stage, representing what has been labelled as the Youth and Old man, while the bolder black calligraphy on gold ground, which occupies two thirds of the page, is by the renowned calligrapher Mir ‘Ali (d. c. 1545) and is taken from a copy of the Qur’an.[xliv] Framing the whole composition, small calligraphic fragments from the Sharafnāma (Book of Honours) by the famous poet Niẓāmi (d. 1209) describe a dispute on the art of drawing between people from China and Rum.[xlv] Reżā’s artwork might be labelled as a drawing, because of the scant use of color, or as an unfinished painting, as the pink youth’s face and hand, in addition to the sashes and the white and red buttons of the youth’s dress, suggest a possible chromatic conception of the piece. The particularity of this work rests on the golden line, nearly invisible today but still characterized by Reżā’s calligraphic strokes, that draws the outlines of the two figures, and the hands, sashes and head of the older man. Reżā’s line stands in stark contrast with the beautiful black calligraphic script of Mir ‘Alī, which is perfectly highlighted on the golden ground. This extremely evocative album folio seems to place at its center Reżā’s work, but its quasi-invisibility blurs the boundaries between drawing and painting, as much as between the framing device and the center.

Fig. 7: Reżā ‘Abbāsi (artist) and Mir Alī al-Kātib (calligrapher), Youth and Old man, 1590s, Isfahan. Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, 46.1 x 30.5 cm.

(The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

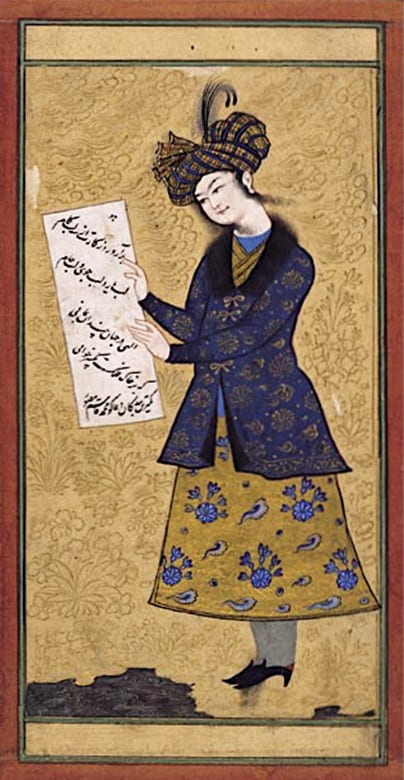

As these examples demonstrate, the qalam of the artist and the calligrapher are intertwined and play on layers of associations between word and image. A particularly striking composition is a single-page painting by Muhammad Qasim (active up to 1659/1660), a contemporary artist and follower of the style of Reżā. A poet and a calligrapher, in one of his single-page paintings, Youth Holding a Letter (fig. 8), the artist addresses, with a purposefully composed poem, a Khan in order “to be referred to for a service.”[xlvi] A refined youth, dressed according to high fashion of the time, holds up a letter, as if inviting the viewer to read it. The painting was meant as a gift, and indeed as a plea as he writes, “a drawing as a letter of appeal,” both showing his skill in painting and his wit in composing verses.[xlvii] He is not only the painter, but also the calligrapher, whose writing style is of high quality. He signs his work at the top of the letter, stating his authorship as a painter: “by the painter” (lī-muṣavvira’), which confirms that he composed the poem, wrote the text and painted the whole sheet.[xlviii] Muhammad Qasim appears self-conscious of the multiple skills in which he excelled: poetry, calligraphy and painting. He employed them all in this artwork, as a disguised petition for commissions from a high-ranking patron.[xlix]

Fig. 8: Muhammad Qasim, Youth holding a Letter, c. 1650. Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, 21.4 x 10.3 cm. © The Aga Khan Museum, Toronto.

The calligraphic line of drawings, inscriptions and paintings underline that its own textural and visual characteristics were of paramount importance to both artists and calligraphers as a mode of personal and individual expression. Balafrej defines it as aesthetics of taḥrīr (outline, writing), as the visual qualities of lines were praised both in writing and in drawing/painting.[l]

The ‘Soul Ravishing’ Artwork

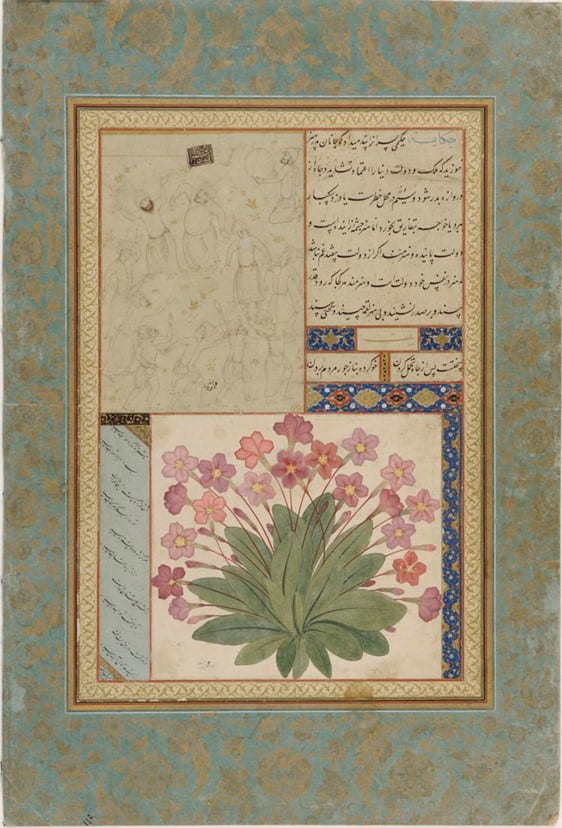

Connections between Sufism (a historical mystical branch of Islam) and calligraphy were well-established in both conceptual and spiritual literature of the time, and these appear intertwined in Composite album folio: Dancing Sufis, Cluster of Primrose and Calligraphic Panels (fig. 9).[li] Just as the Sufis dance in circle, the eyes of the viewer move around the page as if forming a circle too, alternately invited to read the calligraphy of the love poem on the left, copied by Shāh Mahmud al-Nishāpuri (d. c. 1564-65), or the text on the upper right, which is taken from a sixteenth-century manuscript of the Gulestān (Rose-garden) by the celebrated poet Sa’dī (c. 1213-1292). Then, one looks at the line drawing of the Sufis’ dances, attributed to Master Muhammadi of Herāt (active c. 1560-91), and at the primrose watercolor by Ustad Murad (active in the seventeent century) and the illumination, all in a continuous swirl on this rich album page. The beautiful calligraphic lines of Sa’dī’s text extend letters such as the ‘p’ پ , the ’t’ ت , and the ‘b’ ب, that make them resemble some of the wide open arms of the dancers depicted in the nearby drawing (fig. 10).

Fig. 9: Muhammad Ustad Murad (artist) and Shah Mahmud al-Nishapuri (calligrapher), Composite album folio: Dancing Sufis, Cluster of primrose and calligraphic panels, c. 1575, Qazvin. Ink, colour and gold on paper, 45 x 30.3 cm.

(The Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Fig. 10 Detail of Fig. 9.

Calligraphy could lead the Sufi mystic to divine rapture, as much as the dancing practices depicted in the drawing led to a similar mystical state.[lii] According to Bābā Shāh Isfahānī’s treatise, a prominent calligrapher of the time (d. c. 1588), Ādāb al-mashq (Manners of Practice, seventeenth century), calligraphy is a practice of contemplation of the divine, requiring a visionary method of concentration.[liii] In the treatise, the master calligrapher not only needs moderation and balance of the soul (safa) to express the divine beauty with pen and ink, but also to exert authority (sha’n), that is the specification of the divine beauty into form.[liv] Calligraphy then becomes an interior contemplation, and the calligrapher shifts from writing to the mirroring of the invisible divine nature that passes through the Arabic letters.[lv] Bābā Shāh calls the last stage of a calligrapher’s quest for mastery the “imaginative practice”: through the power of his purified imagination, the calligrapher writes new compositions as they originate in his intellect.[lvi]

Imagination, in this way of thinking, is conceptualized as an intermediate world of super-sensory sensibility, in between the visible world and God’s abode.[lvii] This realm is accessible to the mystic through spiritual contemplation and is where theophanies occur.[lviii] This is why it is also named as ‘Creative’ Imagination (hadrat al-khayāl) as it manifests the invisible world to the person that usually sees its exterior manifestations. Through this powerful tool, the mystic sees letters in their spiritual entity and contemplates through them the beauty of God. This is possible because God created the pen and the script, and considering that the Qur’an is the direct, unmediated word of God, the manifestation of the divine essence passes through those very letters.

The act of seeing in Safavid culture was grounded in a rich literature compiled by astronomers and optic scientists. It circulated widely in the writings of poets and commentaries on their original work.[lix] The two most influential treatises were the ones of the polymath Ibn Sīnā (980-1037, also known as Avicenna) and the mathematician, astronomer and physicist al-Ḥasan Ibn al-Ḥaytham (c. 965-1040, also known as Alhazen). The act of perceiving, in Safavid culture, was based on the transferal of the forms seen in the outside world into the imagination.[lx] According to Ibn Sīnā, the image is impressed on the crystalline humor of the eye, which is polished like a mirror, then, it is transferred on the composite sense (al-hiss al-mushtarik). From there, it is transmitted to the imagination (khiyāl) for storage.[lxi] The artist would then relay out of the body these “impressed” images during creative depiction.[lxii]

This process is similar to Bābā Shāh’s conception of the stages followed by the calligrapher to create a new masterfully conceived artwork. His ‘imaginative practice’ is based on the idea that the eyes see the calligraphic form and store them in the imagination for future usage. This conception of sight is referred back to in Dūst Muhammad’s metaphors of “mirror of the mind,” “tablet of vision” and “eye of imagination,” as Roxburgh remarks.[lxiii] In addition, Shams al-Dīn Muhammad, in his preface to an album for Shāh Ismā’īl II (written before 1577), singles out the artist Maulānā Kepek because “the beautiful peri and the gorgeous houri manifested on the tablet of the painter’s mind and the page of the designer’s imagination are not reflected in anyone else’s mind”.[lxiv] The artist’s designs are praised in this passage for their conception inside his imagination. Kepek’s portraits were not “reflected,” as in seen, in anyone else’s mind.

From these writings we can understand that everyone can study and store the images seen in their imagination, but not everyone can understand their ultimate form, what Ibn al- Ḥaytham in his theory of optics (Kitāb al-Manāẓir, c. 1011-1021) defines as the ‘ultimate sensation’.[lxv] Al- Ḥaytham pushes Ibn Sīnā’s theory further by writing that the ultimate sensation takes place only in the brain. His process underlines that the image is not simply stored in the brain, but it is first “sensed,” in other words, comprehended and distinguished using the person’s imagination.[lxvi] The conception that the imagination is part of the very process of perceiving is very important, as, I suggest, it might be related to the Sufi esoteric understanding of reality, exemplified by the belief that the mystic could pierce through the appearance of things and develop a deeper understanding of reality (ḥaqīqah, lit. “truth”) through revelation.[lxvii] Ibn al-Haytham’s theory of perception was one of the most important theories of vision of the time, and continued to be commented and translated well into the sixteenth century.[lxviii] Great artists and calligraphers are believed to have seen the world according to theories of vision and perception specific to the culture of their time. They were able to create the highest forms of art through the faculty of their own creative imagination and perception of the world.

Drawing, in particular, is the artistic media in between painting and calligraphy that manifests the aesthetic of the line, the individuality of the artist, and the possibility for contemplation. In addition, Safavid art historiography fashioned the symmetry between calligraphy and depiction, through common historical origins: they were created by God and practiced by numerous prophets, chief among them is ‘Ali (601-661, the first Imam of Shi’a Islam, cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad).[lxix] In Qāżī Ahmad’s Gulestān-i Hunar, ‘Ali created an “Islamic soul-ravishing tracing,” which can be defined as that inner understanding of reality that “ravishes” the soul by ecstatic rapture.[lxx]

The ‘soul-ravishing’ concept is applied both to painting and calligraphy in the writings of the time and might indeed summarize the effect of the theories of vision and perception discussed here. This affected both viewers and readers, and it can be defined as the feeling one experiences in front of extreme beauty, which makes the soul itself vibrate in awe. This unique experience is the result of the most beautiful tracing, whether painted or calligraphed. Qāżī Ahmad quotes that “an excellent handwriting, O brother, is soul ravishing,” and the same adjective is used to describe the writing of Maulānā ‘Abd al-Karim (active in the sixteenth century), and Sultān-Ibrāhīm Mīrzā.[lxxi] In addition, Qāżī Ahmad also describes artist Maulānā Habibullāh of Sāva (active 1550-1650) in regard to art as “a ravisher of the souls of his contemporaries,” which interestingly notes how both calligraphy and painting could have a similar effect on the viewer.[lxxii] Thus, it is possible to suggest that both calligraphy and painting, masterfully executed, could ravish the soul of the viewers as they both shared the potentiality for contemplation.

Conclusion

This paper has explored the role of the artist in relation to that of the calligrapher and the interplay of calligraphy and painting/drawing in sixteenth and seventeenth century Iran. At this time, artists started to sign their work on a more regular basis, often inscribing information about the making of the artworks themselves. Some artists such as Muhammad Qasim were also poets and calligraphers, and the dedicatory lines in their works are usually written in elegant letters.

Moreover, official historical accounts and art treatises began to offer a different way of judging and describing the artists’ work, mostly based on the artist’s moral posture, or through the ‘theory of the two qalams.’ Calligraphy and depiction were thought, or at least claimed, to be closer than what scholarship seems to believe. Despite research that has concentrated on the ‘theory of the two qalams’ and the ‘seven principles of painting,’ scholarly attention appears to be divided between calligraphy, usually linked to religious studies, and painting/drawing. This paper has shed light on the urgency of intersectional studies whereby calligraphy and drawing are studied together as related practices.

Theories of perception and imagination suggest that the creative act of both practitioners were closely related. Works of great art/calligraphy had to be studied closely and only when stored in the students’ imagination, could they be used in creative ways to produce ‘soul-ravishing’ works of art. Artists’ and calligraphers’ artworks were often juxtaposed by contemporary collectors in album pages and even pasted on the same folio. The consonances in production, fruition and reception of both calligraphers’ and artists’ work point to the possibility of the sharing of these ways of looking and being. These “pages of time”,[lxxiii] which were perfumed as rose-gardens, precious as jewels, and created by the qalam scattering pearls, stretched beyond chronological boundaries and encompassed infinite possibilities for ecstatic experiences of the soul.

Endnotes

[i] Acknowledgment: I would like to thank Dr Sussan Babaie, my supervisor, Dr Lucia Tantardini and Dr Geri Della Rocca de Candal; my family, my boyfriend, all my friends and God, above all, for their unfailing help. I have used the International Journal of Middle East Studies transliteration system for Persian and Arabic.

[ii] On Reżā see Sir Thomas W. Arnold, “The Riza Abbasi Ms. in the Victoria and Albert Museum”, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 38, no. 215 (February, 1921), 59-63 & 66-67; Jeanne Gobeaux-Thonet, “Aqa Riza ou Riza Abbasi?”, Melanges de Philologie Orientale publiés a l’occasion du Xe anniversaire de la création de l’Institut Superieur d’Histoire et de Littérature Orientales de l’Université de Liège (Liege, 1932), 105-110; Ivan Stchoukine, Les Peintures des Manuscrits de Shah ‘Abbas Ier à la Fin des Safavids (Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1964); Sheila R. Canby, “Age and Time in the Work of Riza”, in Persian Masters: Five Centuries of Painting, ed. Sheila R. Canby (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1990), 71-84; see also Reżā’s monograph by Sheila R. Canby, The Rebellious Reformer: The Drawings and Paintings of Riza-yi Abbasi of Isfahan (London: Azimuth, 1996).

[iii] See also the analysis by Canby, The Rebellious Reformer, 90 & 92; illustrated: 85.

[iv] He died in the month of Muharram in 1015 AH.

[v] Qāzī Mīr Ahmad Ibrāhīmī Husaynī Qumī, Gulistān-i hunar: Tazkira-yi khushnivīsān va naqqāshān, ed. by Ahmad Suhaylī Khvānsārī (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Bunyād-i Farhang-i Irān, 1352/1973) and trans. by Vladimir Minorsky, Calligraphers and Painters: A Treatise by Qadi Ahmad, son of Mir Munshi (circa A.H. 1015/1606), Freer Gallery of Art Occasional Papers, v. 3, no. 2 (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1959), 192-193.

[vi] The Gulestān-i Hunar was written in 1006 AH. The treatise is known in two versions, the second is dated c. 1015 AH/1606 AD, for a commentary and translation see Minorsky, Calligraphers and Painters, pp. 34-39. On Qāżī Ahmad see also Massumeh Farhad and Marianna Shreve Simpson, “Sources for the Study of Safavid Painting and Patronage, or Méfiez-vous de Qazi Ahmad”, in Muqarnas, vol. 10, (1993), pp. 286-291; and Kambiz Eslami, “Golestān-e Honar”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, online edition, 2020, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/golestan-e-honar#article-tags-overlay (accessed 22nd June 2020).

[vii] 969-1043 AH.

[viii] On the history of the Safavids the literature is vast. On Shah ‘Abbas I see Sheila R. Canby, Shah ‘Abbas: The Remaking of Iran (London: British Museum Press, 2009). On the Safavid dynasty see Sussan Babaie, Isfahan and Its Palaces: Statecraft, Shi’ism and the Architecture of Conviviality in Early Modern Iran (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008); Sussan Babaie, “The Safavid Empire of Persia: The Padshah of the Inhabited Quarter of the Globe”, in The Great Empires of Asia, ed. Jim Masselos (Oakland: University of California Press, 2010), 136-165; and Sussan Babaie, Kathryn Babayan, Ina Baghdiantz-McCabe, and Massumeh Farhad, Slaves of the Shah: New Elites of Safavid Iran (London: I.B. Tauris, 2018).

[ix] Iskandar Beg Munshī, The History of Shah ‘Abbas the Great: Tārīk-e ‘Alamārā-ye ‘Abbāsī, transl. Roger Savory (Boulder: Westview, 1978), 273.

[x] On Persian drawings see Armenag Sakisian, “Persian Drawings”, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 69, n. 400 (July, 1936), 14-15 & 18-20; B.W. Robinson, Drawings of the Masters: Persian Drawings from the 14th to the 19th century (New York: Shorewood Publishers, 1965); Esın Atıl, The Brush of the Masters: Drawings from Iran and India (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978); Stuart Cary Welch, Wonders of the Age: Masterpieces of Early Safavid Painting, 1501-1576 (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1979); Marie Lukens Swietochowski and Sussan Babaie, Persian Drawings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989); Sheila R. Canby, “The Pen or the Brush? An Inquiry into the Technique of Late Safavid Drawings”, in Persian Painting from the Mongols to the Qajars: Studies in Honour of Basil W. Robinson, ed. Robert Hillenbrand (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2000), 75-82, I thank Dr Canby for sharing a copy of her article; Sussan Babaie, “The Sound of the Image/the Image of the Sound: Narrativity in Persian Art of the Seventeenth Century”, Islamic Art and Literature, ed. Oleg Grabar and Cynthia Robinson (Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2001); David J. Roxburgh, “Persian Drawing, c. 1400-1450: Materials and Creative Procedures”, Muqarnas, vol. 19 (2002), pp. 44-77; and David J. Roxburgh, “The Pen of Depiction: Drawings of 15th– and 16th-Century Iran”, in Studies in Islamic and Later Indian Art from the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 2002), 43-57.

[xi] This is not in relation to European artists, but only in the Safavid context.

[xii] Quoted in David Roxburgh, Prefacing the Image: The Writing of Art History in Sixteenth-Century Iran (Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill, 2001), 50.

[xiii] It was indeed the normative practice to include all kinds of artists and craftsmen in the tazkera genre usually titled as the biographies of poets. The tazkera is a compilation of short biographical entries on the poets, a well-used example is the Tazkera-i Nasrābādi, see Mahmoud Fotoohi, “Tadkera-ye Nasrābādi”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/tadkera-ye-nasrabadi (accessed on 22nd June 2020); for an early study see N. Bland, “On the Earliest Persian Biography of Poets, by Muhammad Aúfi, and on Some Other Works of the Class Called Tazkirat ul Shuará”, in The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 9 (1847), 111-176; for a more recent study see Hossein Monttaghi-far, “The traditions of Persian ‘Tazkirah’ Writing in the 18th and 19th Centuries and Some Special Hints”, Advanced Information Sciences and Service Sciences, vol. 2, no. 3 (September 2010, accessed 22nd June 2020), https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/94c2/1d97d77a25ae9f363aea4f300af7e320091b.pdf.

[xiv] Yves Porter, “From the ‘Theory of the Two Qalams’ to the ‘Seven Principles of Painting’: Theory, Terminology, and Practice in Persian Classical Painting”, in Muqarnas, vol. 17 (2000), particularly: 109.

[xv] Porter, “From the ‘Theory of the Two Qalams’”, 109.

[xvi] Roxburgh, Prefacing the Image, especially: 51.

[xvii] Roxburgh, Ibid., 2.

[xviii] See Annemarie Schimmel, Calligraphy and Islamic Culture (London: I.B. Tauris, 1990), 1-2; Carl W. Ernst, “The Spirit of Islamic Calligraphy: Bābā Shāh Isfahānī’s Ādāb al-mashq”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 112, no. 2 (April-June 1992), 284-285; Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), 6-7; and Annemarie Schimmel, Mystical Dimensions of Islam (North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1977). In the article I usually address the calligrapher with ‘him/his’ pronoun, although calligraphers were not always men, see Schimmel, Calligraphy and Islamic Culture, 46-47. However, the calligraphers discussed in this article were all men.

[xix] Wheeler M. Thackston, “An Album made by Kamaluddin Bihzad, Preface by Khwandamir”, Album Prefaces and other Documents in the History of Calligraphers and Painters (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2014), 42.

[xx] Dūst Muhammad’s opinion on Anisi’s calligraphy, see Thackston, Ibid., 10.

[xxi] Dūst Muhammad on Sultān Muhammad Khandān’s calligraphy, see Thackston, Ibid., 10; and Qāżī Ahmad on Yaqut’s calligraphy, see Minorsky, Ibid., 58.

[xxii] Dūst Muhammad on Muhammad Qasim Shadishah’s calligraphy, see Thackston, Ibid., 11.

[xxiii] Dūst Muhammad on Khvāja Ibrāhīm’s calligraphy, see Thackston, Ibid., 11.

[xxiv] Thackston, Ibid., 10 & p. 21, for a translation and original text in Persian of the Preface by Mālik Daylamī see Thackston, Ibid., 18-21.

[xxv] See Thackston, Ibid., 10.

[xxvi] See Minorsky, Ibid., 61 & 66. Similarly, according to Qāżī Ahmad, Mir-Munshī of Qūm “possessed a saintly spirit and an angelic disposition”, Ibid., 77.

[xxvii] Minorsky, Calligraphers and Painters, 106-123.

[xxviii] Ibid., 122.

[xxix] For their comments on Sadiqi Beg see Minorsky, Calligraphers and Painters, 191; and Iskandar Beg Munshī, The History of Shah ‘Abbas the Great: Tārīkh-e ‘Alamārā-ye ‘Abbāsī, transl. Roger Savory (Boulder: Westview, 1978), 271-272.

[xxx] Minorsky, Ibid., 183.

[xxxi] Ibid., p. 185. Interestingly, Qāżī Ahmad extends the good nature of character to the success of bookbinding and leather-binding too by writing on Maulānā Qāsim-Beg Tabrizī who had the nature of a dervish and was self-effacing (fānī), see Minorsky, Ibid., 193-194.

[xxxii] Thackston, Album Prefaces and Other Documents, 42.

[xxxiii] Abolala Soudavar, Art of the Persian Courts (New York: Rizzoli, 1992), 258-259.

[xxxiv] On the variable sources of Qāżī Ahmad see Farhad and Simpson, “Sources for the Study of Safavid Painting and Patronage”, 286-291.

[xxxv] For example see Lamia Balafrej, The Making of the Artist in Late Timurid Painting (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctvggx3q1, accessed 16th June 2020); Canby, The Rebellious Reformer, 43-94; David Roxburgh, “Persian Drawing”, 71-72; on the use of the brush and the pen see Canby, “The Pen or the Brush?”, 75-82.

[xxxvi] Balafrej, The Making of the Artist, 154-156.

[xxxvii] On different techniques of pouncing see Roxburgh, “Persian Drawing”, 61.

[xxxviii] Translated by Sussan Babaie in Swietochowski and Babaie, Persian Drawings, 7.

[xxxix] Babaie also makes a case similar to this one in “The Sound of the Image/the Image of the Sound”, 154.

[xl] The date is 9th April 1642, see Massumeh Farhad, “Safavid Single Page Painting, 1629-1666”, PhD diss. (Harvard University, 1987), 176.

[xli] Massumeh Farhad argues was one of his friends: Farhad, Ibid., 117. Other drawings that were meant as gifts are Reżā’s Man with a Pitchfork, dated 4 Safar 1044 AH (11 July 1634), dedicated to his son Muhammad Shafi’ (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, available at: https://collections.lacma.org/node/240001); Mu’īn’s Youth carrying a rooster, dated 15 Dhu-l-hijja 1066 (4 October 1656), made ‘in haste’ for his son Aqa Zaman (Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin, MS 265, no. 2), illustrated in Massumeh Farhad, “The Art of Muʿin Musavvir: A Mirror of His Times”, in Persian Masters: Five Centuries of Painting, ed. Sheila R. Canby (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1990), 117; Mu’īn’s Portrait of Reżā ‘Abbasī, which was completed at the request of his son Muhammad-Nasir (Princeton University Library, available at: https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/6959339), on the debated dating of this painting see Farhad, “The Art of Muʿin Musavvir”, 120 & 124.

[xlii] Massumeh Farhad, “An Artist’s Impression: Mu’in Musavvir’s ‘Tiger attacking a Youth’ ”, Muqarnas, vol. 9 (1992), 117.

[xliii] The ‘signature’ in the drawing is mashq-i Aqā Reżā (Aqā Reżā drew [it]), which differs from other drawings and paintings attributed to him, only five of the works that Canby attributes to him are signed Aqā Reżā. Canby notes that the multiple forms of signatures: Aqā Reżā, Reżā or Reżā-yi ‘Abbāsi provoked discussion as to whether ‘Reżā’ was one or two artists, on the Reżā Question see Canby, The Rebellious Reformer, 21-22; and 201-203 for a full historiography on this debate. I follow Canby’s argument that it was one artist who signed differently in successive periods of his life.

[xliv] For an analysis of Mir ‘Alī’s work see Wheeler M. Thackston, “Calligraphy in the Albums”, in Muraqqa’: Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library Dublin, ed. Elaine Wright (Alexandria: Art Services International, 2008), 154-158.

[xlv] The subject is studied by Priscilla P. Soucek, “Nizami on Painters and Painting”, Islamic art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 1 (1972), 9-21.

[xlvi] For the full translation see Farhad, “Safavid Single Page Painting”, 124.

[xlvii] Farhad, Ibid., 124.

[xlviii] Ibid, 129.

[xlix] The interpretation of this work as a disguised petition is argued for in Farhad, Ibid., 126-129.

[l] Balafrej, “Figural Line/ Persian Drawing c. 1390-1450”, Drawing Education: Worldwide! Continuities – Transfers – Mixtures, eds. Nino Nanobashvili and Tobias Teutenberg (Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Publishing, 2019), 24.

[li] On Sufism and calligraphy see Schimmel, Calligraphy and Islamic Culture, and Schimmel, Mystical Dimensions of Islam; Ernst, “The Spirit of Islamic Calligraphy”, 279-286 and Carl W. Ernst, “Sufism and the Aesthetics of Penmanship in Sirāj al-Shīrāzī’s Tuḥfat al-Muḥibbīn (1454)”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 129, no. 3 (July-September 2009), 431-442.

[lii] See Ernst, “The Spirit of Islamic Calligraphy”, 284-285.

[liii] Ernst, Ibid., 279.

[liv] Ernst, Ibid., 282-284.

[lv] Ernst, Ibid., 284.

[lvi] Ernst, Ibid., 284.

[lvii] This concept was particularly developed in the Sufi school of Ibn al-‘Arabi (1165-1240), see Henry Corbin, transl. by Ralph Manheim, Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn Arabi (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), particularly: 182.

[lviii] Ibn al-‘Arabi quoted in Corbin, Ibid., 182.

[lix] On the Safavid culture of seeing see Gülru Necipoğlu “The scrutinizing gaze in the aesthetics of Islamic visual cultures: Sight, insight, and desire”, Muqarnas, vol. 32 (Brill: 2015), 23-61.

[lx] See Roxburgh, Prefacing the Image, 184-186, and Soucek, “Nizami on Painters and Painting”, 14-15.

[lxi] Soucek, “Nizami on Painters and Painting”, 14.

[lxii] Roxburgh, Prefacing the Image, 185.

[lxiii] Roxburgh, Ibid., 185.

[lxiv] Thackston, Ibid., 34.

[lxv] See Ibn al-Ḥaytham, Optics, transl. with an introduction and commentary by A.I. Sabra (London: The Warburg Institute, 1989), 84.

[lxvi] On sensation and form see paragraph n. 80, in al-Ḥaytham, Optics, 88; for the comprehension of the image through imagination see also: 208; on the faculty of remembering, and therefore the imagination as ‘storage’ of things seen see: 212. David Roxburgh argues that the creative role of the artist might be understood as the faculty of transforming what is seen into an absolute concept, the perception of the artist’s mind is filtered through his imaginative faculty in the act of making an image, Prefacing the Image, 188. However, I would argue that according to Ibn al-Haytham what is seen is comprehended before the artist creates something new.

[lxvii] On Sufism the literature is vast. On the concept of ḥaqīqah, see the Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Ḥaqīqah”, https://www.britannica.com/topic/haqiqah (accessed 04th May 2021).

[lxviii] On the Early Modern reception of the writings of Ibn al-Haytham see Gülru Necipoğlu, Ibid., particularly: 37.

[lxix] David J. Roxburgh, “Beyond Books: The Art and Practice of the Single-Page Drawing in Safavid Iran”, In Harmony: The Norma Jean Calderwood Collection of Islamic Art, ed. Mary McWilliams (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Art Museums, 2013), 140.

[lxx] Minorsky, Calligraphers and Painters, 175. On the people of the Prophet’s house see Fahmida Suleman and Shainool Jiwa, “Shi’i art and ritual: contexts, definitions and expressions”, in People of the Prophet’s House, 13-24. On the Safavid religious context see Kathryn Babayan, Mystics, Monarchs and Messiahs: Cultural Landscapes of Early Modern Iran (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003); Rula Jurdi Abisaab, Converting Persia: Religion and Power in the Safavid Empire (London: I.B. Tauris, 2004); Said Amir Arjomand, The Shadow of God and the Hidden Imam: Religion, Political Order, and Societal Change in Shi’ite Iran from the Beginning to 1890 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984).

[lxxi] Minorsky, Calligraphers and Painters, 51 & 101 & 155 respectively.

[lxxii] Minorsky, Ibid., 191.

[lxxiii] From Khvāndāmīr’s Ḥabīb al-siyar, quoted in Roxburgh, Prefacing the Image, 126.