Le Lucien Sun

University of Chicago

Abstract

Archaeologists have recently discovered several paintings of filial piety stories from Yuan Period tombs in north China that are distinct from their Song–Jin precedents. They are decorated with complicated natural or architectural backgrounds, and often combine multiple stories into one picture. They are also larger in scale and are relocated to the center of display from originally unnoticeable nooks within the tomb chamber. In this paper, I examine filial piety paintings of this kind from three individual tombs: Weishi tomb in Henan Province, Zhuozhou tomb in Hebei Province, and Tunliu tomb in Shanxi Province. These tombs cover the geographic scope of north China, which had a long tradition of depicting filial piety stories.

Through visual analysis, I attempt to correlate this pictorial transition with the agency of tomb artisans and their clients in the production of tomb art. Artisans working on these tombs continued, on the one hand, to capitalize on the preexistent repertory of modular design from earlier periods, including rhymed mnemonics and painting manuals. On the other hand, they were always inspired by new trends in the textual, publishing, and theatrical domains that grew more palpable during the Yuan Period. Additionally, the tombs’ occupants or their family members, usually wealthy landlords and occasionally minor clerk-officials, commissioned this new type of filial piety image in hopes of maintaining family solidarity and social repute to ensure their managerial authority in the local community.

Admittedly, the three case studies by no means provide, nor do I intend, an inclusive account of the continuities and metamorphoses in the mortuary practice of north China. These silent pictures and fragmented words preserved underground do shed light, however, on the complicated interactions between certain tomb artisans and their clients.

Artisan and Clientele:

“New” Images of Filial Piety Stories at Tombs in Thirteenth- through Fourteenth-Century North China

Introduction

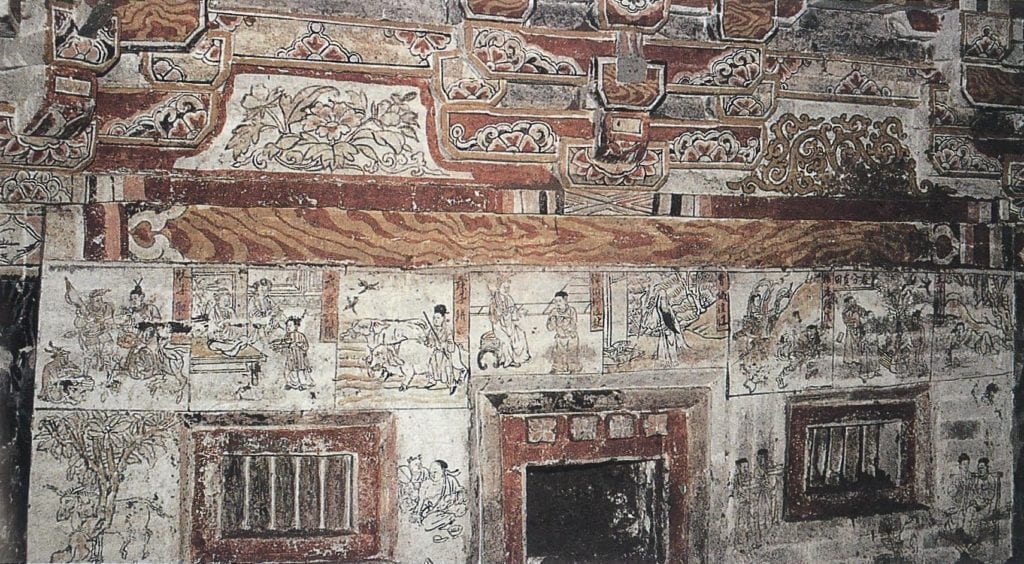

In 2002 archaeologists unearthed a fourteenth-century brick tomb in Zhuozhou, Hebei Province, China. On the southeastern and the southwestern walls of the octagonal tomb chamber are two unique paintings of filial piety stories. Dozens of filial tales that embody the prized Confucian virtue of respecting one’s parents and elders are conflated into two self-contained large compositions; the lines and strokes of a hilly landscape scene demarcate story boundaries, so as not to confuse the individual narratives (Figs. 1A and 1B).[1]

Figures 1A and 1B. Filial piety stories (the story of Zhao Xiao at the upper-left corner of Fig. 1B), 1339 CE. Southeastern and southwestern walls of the Zhuozhou tomb, Hebei. From Xu Haifeng et al., “Hebei Zhuozhou Yuandai bihuamu,” Wenwu, no. 3 (2004), 53, figs. 24, 25.

Figures 1A and 1B. Filial piety stories (the story of Zhao Xiao at the upper-left corner of Fig. 1B), 1339 CE. Southeastern and southwestern walls of the Zhuozhou tomb, Hebei. From Xu Haifeng et al., “Hebei Zhuozhou Yuandai bihuamu,” Wenwu, no. 3 (2004), 53, figs. 24, 25.

The aforementioned pictorial properties distinguish these paintings from the myriad filial piety images discovered annually in tombs in China. A diachronic survey of such images suggests a tenuous parallel between the Zhuozhou case and its archaic precedents nearly one millennium earlier—stone carvings on sarcophagi that similarly place multiple filial piety stories on a continuous mountainous terrain.[2] After a period of diminution in Tang (618–907 CE), the image of filial tales once again became a popular motif in the overall pictorial program of Han Chinese tombs in north China during the Song–Yuan periods (spanning the tenth to fourteenth centuries).[3] These images are usually monoscenic and small in size, devoid of sophisticated background, and positioned under the architrave of the tomb chamber (see, for instance, Fig. 2). It was also during this time that “The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety,” an influential set of didactic tales, took shape. Previous scholarship on these excavated images has been mostly restricted to iconography and functionality.[4]

Figure 2. Filial piety stories, 1174 CE. Western walls of the Changzi tomb, Shanxi. From “Shanxi Changzi xian Xiaoguan cun Jindai jinian bihuamu,” Wenwu, no. 10 (2008), 63, fig. 6.

The existing literature usually categorizes images of filial piety from the tenth to fourteenth centuries into a unitary type, but their internal variance in composition, size, and position within the tomb space requires further investigation. Recently discovered filial piety images in Yuan period (1271–1368) tombs reveal new modes that are different from the formerly predominant monoscenic, small-sized format, and prove that the Zhuozhou tomb is far from being an isolated case (see Table 1). For example, images of filial sons in several tombs were framed by carefully painted natural elements such as trees and stones (see Figs. 3 and 13); the conflation of multiple narratives within one painted composition is visible in two other tombs (see Fig. 6). Earlier conventions of filial piety images certainly continued to prevail in most tombs of the period, but the tombs whose images of filial sons are so large as to occupy the main register of the walls should not be overlooked. While acknowledging the pictorial and narrative polysemy of these “new” images, we should pose three questions: Can we locate the sources of these new forms in both the pictorial traditions and the new trends of the Yuan period? If so, through which specific practices in tomb construction did artisans combine the conventional and the trendy? What role did their clients from the local community play in the formation of these new images of filial piety?

In the Weishi and the Zhuozhou cases, I will identify certain literary and visual sources, architectural schemes, and modular conventions as the pertinent artisanal forms of knowledge that shaped these filial piety images. In picturing filial piety stories, these workshop artisans would have strived to synthesize tradition and innovation. In the second half of the article, starting from the Zhuozhou case and expanding further in the Tunliu case, I will delineate the multivalent significance of the murals possible in the eyes of the clients who commissioned the tomb building. Under the particular conditions in north China at this time, some families of the deceased would have attached certain mediated social meanings such as communal leadership, familial cohesion, and social reputation to the tomb murals.

Sources in Vogue: Weishi Tomb in Henan

Archaeologists in 2000 excavated a Yuan period tomb in Weishi County, Henan Province. The four walls of the rectangular chamber are divided into two registers by a band of brackets commonly found in Chinese wooden architecture. A niche at the center of each lower register divides the space in half. On the northern wall, portraits of the male and female tomb occupants appear on each half; on the eastern wall, a filial son image occupies the northern section; symmetrically on the western wall, another image of a filial piety story takes up the northern portion. In addition, the upper register above the bracket band is also embellished with paintings, and the two of them on the northern wall are images of filial sons.[5]

The four images of filial piety draw from a confluence of three popular sources of the Yuan period: varied versions of stories in vernacular literature, mass-produced illustrated prints, and theater. The picture of Dong Yong, a legendary filial paragon (Fig. 3), well testifies to the variable nature of popular literature. His hagiography was preserved in a late tenth-century encyclopedia: When Yong’s father died, he had to borrow money from a landlord to afford a decent funeral. In order to repay the loan, he was ready to sell himself as a slave. Yong later met a lady who asked him to marry her so that they could pay back the debt together; the lady subsequently told Yong that she was a weaving-girl from Heaven. Deeply touched by his utmost filial piety, she had descended to assist him. Since the debt had now been repaid, she mounted on a cloud and flew away.[6]

Figure 3. Story of Dongyong encountering the weaving-girl from Heaven, Yuan dynasty. Eastern wall of the Weishi tomb, Henan. From Liu et al., “Henan Weishixian,” 113, fig. 3.

The most common representation of this narrative found in mid-imperial tombs from this region depicts a fairy departing from her husband Dong Yong on a tapering cloud, while Dong Yong looks up sorrowfully on the other side of the diagonal. The image in the Weishi tomb, however, seems to illustrate the meeting scene rather than the departing one, with several elements unmentioned in the tenth-century text: a group of burial mounds, a peculiar tree on the left, and floating clouds in the background.

If we turn to other variations of this story in folkloric texts, we may find relevant textual support for such a depiction. Hong Pian (c. 1540s CE) once collected a storytelling script of the Dong Yong story that synopsizes the couple’s first meeting scene as follows: After Dong Yong buried his father “at the ancestral graveyard in the South Mountain,” he met the weaving-girl from Heaven under a pagoda tree (huaishu).[7] The two soon entreated the pagoda tree to be the matchmaker who witnessed their union.[8]

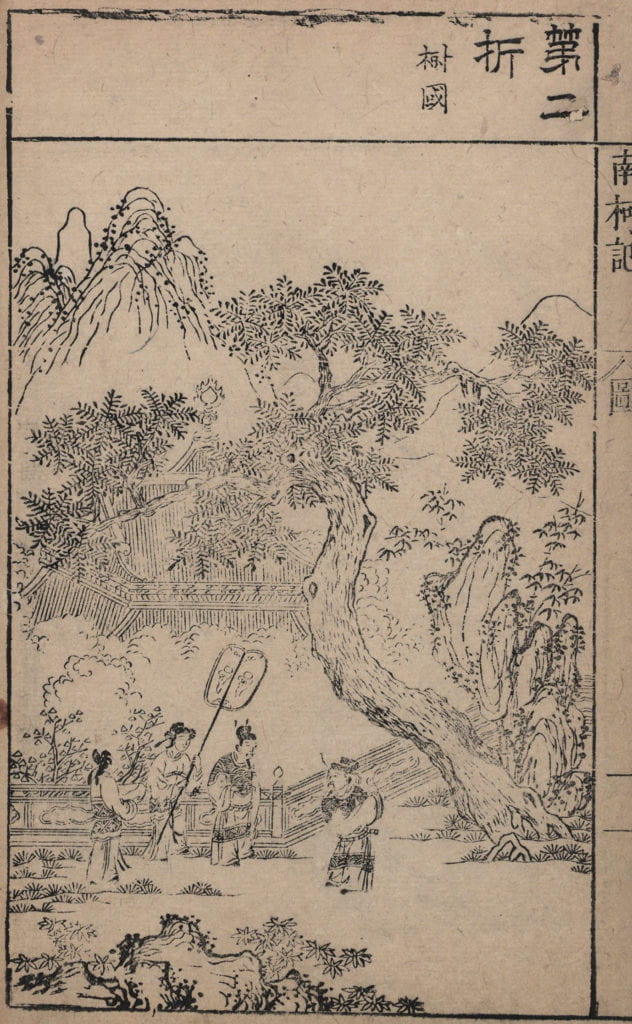

Is it possible that tomb artisans in Weishi happened to consult a version of the legend that was closer o Hong Pian’s script? For one, the multiple hilly graves in the Weishi version coincide with the script text, “ancestral graveyard.” I found only two roughly coeval images of Dong Yong that picture his father’s tomb—one is at a tomb in Shanxi,[9] and another is an illustration from the reprint of a Yuan-edition book.[10] Yet each of these two examples depicts only one grave. Furthermore, the tree is noteworthy. The prominent tree in the image at the Weishi tomb is unmistakably a pagoda tree whose foliage resembles another pagoda tree image in an illustrated theater script (Fig. 4).[11] Moreover, within the Weishi tomb itself this pagoda tree differs distinctly from the willow or wattle trees depicted in other paintings, indicating the artisan’s intentional rendering of a pagoda tree in the story of Dong Yong. Such a choice is consistent with the episode in the cited script that metaphorically describes the pagoda tree as a matchmaker. This previously absent motif of the pagoda tree gradually gained significance in late imperial China, to the point where the story was later titled The Tale of Pagoda Tree’s Shade.

Figure 4. Image of a pagoda tree in the Record of Southern Bough, Wanli’s reign, Ming dynasty. National Central Library.

To account for the emergence of this new representation of the Dong Yong story, it is necessary to consider the changes in the set of Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety in the Yuan dynasty. During the earlier Song–Jin periods, the set of Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety found in tombs remained considerably stable, tallying with a book compiled in Goryeo Korea, which had a strong connection to north China.[12] Under Mongolian rule, however, the stability of such a combination fell apart, and there was a growing tendency to include new stories of the Twenty-four Paragons from the south.[13] This interregional fusion of filial piety stories was situated within a larger north-south exchange of art, books, commodities, and thoughts under Pax Mongolica,[14] allowing master copies of filial piety stories used by artisan workshops from one region to appropriate new narratives and pictorial repertoires from other regions.

Apart from textual variations, artisans of the Weishi tomb might have referred to prevalent visual sources in prints, theater, and daily artifacts in their rendering of filial piety stories.[15] Although scholars are not able to pinpoint artisans’ contact with these materials, fragmentary evidence nevertheless allows a glimpse into such a correspondence.

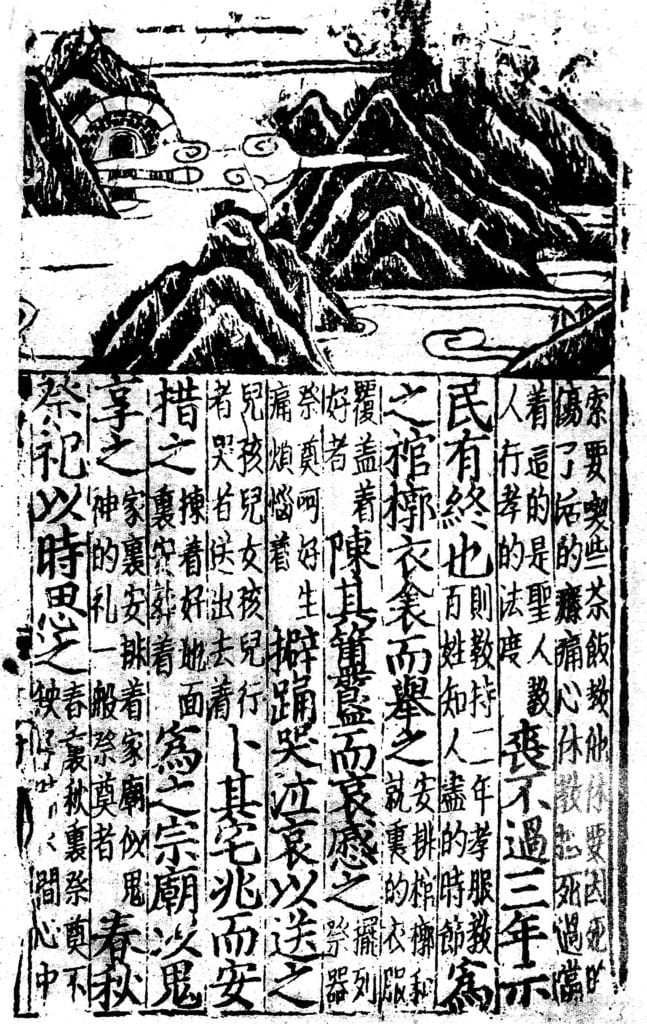

An illustrated edition of the Classic of Filial Piety, published by a Uighur, Guan Yunshi, in 1308, combines the Confucian text with vernacular annotations and illustrations. The configuration of a tombstone and a grave mound on one page (Fig. 5) is comparable to those in the Dong Yong image. Moreover, the grave in the tomb painting is situated against a billow of clouds with ceramic vessels offered in the front, as if it were glossing the underlined command on the same page: “Set forth the sacrificial vessels, the sight of which fills the mourners with sorrow.”[16] Guan claims in the preface that he published this booklet with the intention of “helping ordinary men and women to know well the way of filial piety, and perhaps slightly educating the ignorant masses about moral sense.”[17] Unlike the renowned hand scroll of the same subject-matter by Li Gonglin (1049–1106 CE),[18] Guan’s prints were meant for public distribution. It is conceivable that tomb artisans were able to consult such materials when painting their murals.

Figure 5. Illustration in the New Edition of the Fully Illustrated Chengzhai Classic of Filial Piety, Yuan dynasty. From Guan, Xinkan quanxiang, 15.

The predominant performing art and the related pictorial scripts during the Yuan period were another plausible source.[19] The northern section of today’s Henan Province, where the Weishi tomb is located, had been a regional center of variety plays (zaju) since the eleventh century.[20] Although examples of zaju decoration in tombs have been successively unearthed,[21] and several entries on the theme of filial piety survived in coeval catalogs of plays,[22] few scholars have studied their interconnection for the lack of direct evidence. It is critical, however, to note the latent impact of the theater on the visual construction of the filial piety images and their position in the tomb space.

The filial piety images at the Weishi tomb fall into the category of narrative figure painting, which is also visible on contemporary porcelain pieces that are believed to have associations with the flourishing theatric activities of the Yuan Dynasty.[23] Much as porcelain artisans synthesized theatrical staging and printed illustrations onto ceramics, painters from tomb-building workshops encoded their everyday visual experience into tomb paintings.

The two images of filial sons located at the upper register of the rear wall are conceivably related to theater. In relation to the total mortuary space, these two paintings occupy, strangely, not the lower register of the northern wall where the rest of filial piety images are placed, but the upper, spatially disrupting the orderly pictorial program of the tomb. Separating paintings that share the same subject matter is an uncommon practice, but the overall composition of the entire northern wall recalls the building incised on the head panel of a Daoist sarcophagus in which the theatrical stage is located on the second floor.[24] In both cases, the play is performed above the viewers and surmounts an open-space architectonic element, either a half-open door or a recessed niche. By placing two images of filial sons in an elevated position, artisans might have conceptually envisaged a scenario in which the offspring of the tomb occupants would enter this chamber and look up to the ongoing performance of filial piety plays.

In summary, artisans of the Weishi tomb incorporated new narratives and visual trends in picturing filial piety stories. Their creation departs from the prescribed conventions of filial piety illustrations, bespeaking the vogue in vernacular literature, woodblock printing, and stage performance.

Tomb Artisan Practice: Zhuozhou Tomb in Hebei

As discussed in the introduction, the composition of the two filial piety murals at Zhuozhou tomb was unusual for its time: instead of having monoscenic images of each filial paragon demarcated by clearly drawn boundary lines (see Fig. 2), the images of each independent story were conflated into a whole against a natural setting (Figs. 1A and 1B). When the tomb artisans painted these two murals, however, they by no means started from scratch and invented everything on their own; rather, as Paul Katz rightly observes in his study of coeval artisans working for Buddhist and Daoist temples, they still “worked within a centuries-old tradition.”[25] The question then becomes: which aspects of the mural remain in the tradition of filial piety images, and which depart from it and are indeed the creation of the artisans? What is the dialectic between continuity and change in the practice of tomb artisans?

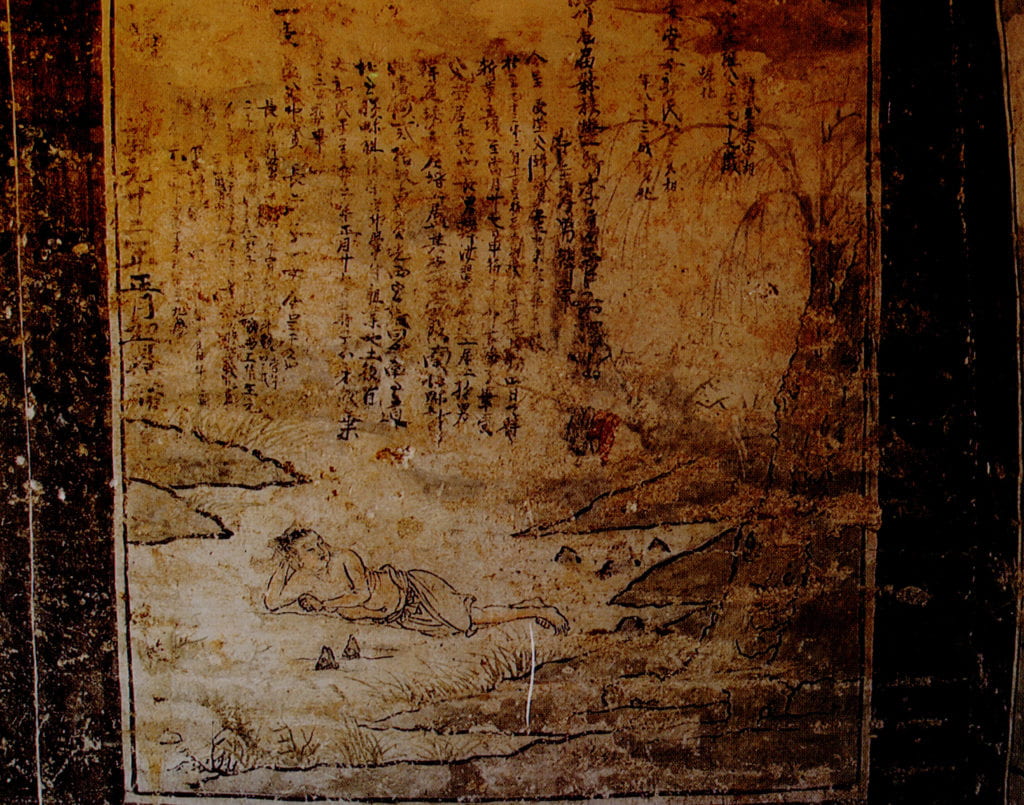

If we look closer at each story unit in the two murals, we will notice that the depiction of the story scene closely follows the pictorial conventions of earlier times. At the micro-level, specific visual elements that serve as the iconographic signifiers tied closely to a particular story are present. An image with bamboo growing on the ground, for example, would be instantly recognized by an informed viewer as the representation of the story of Meng Zong in the Twenty-four Paragons. At the macro-level, the pictorial space—that is, the holistic, fixed spatial arrangement of several elements in one episode of a story—also follows the Song–Jin (tenth- to thirteenth-century) convention.[26] The story of Zhao Xiao (Fig. 1B upper left), for instance, demonstrates this formula:

In the times of upheaval, cannibalism was practiced. [Zhao Xiao’s] younger brother Li was taken by the rebel-bandit. After hearing this, Xiao surrendered to the bandit and said, “Li has starved for too long and became gaunt, but I am fleshy and plump.” The bandits were daunted and did not eat them in the end.[27]

The painting at the Zhuozhou tomb illustrates the scene of Xiao confronting the bandit. Xiao, having his shirt unbuttoned, is kneeling down and beseeching the chief, as if demonstrating that he is more palatable. The leader of the bandits sits on the other side of the picture, stretching one leg forward while slightly crossing the other. Pictures that represent the same story from earlier tombs (Figs. 6 and 7) stage this episode in a similar fashion, except that some reverse the spatial arrangement or simply have a different number of entourages. Additionally, the sitting posture of the bandit chief was often used to portray other male figures in tomb murals or printed books.[28] Although no images identical to those in Zhuozhou have been found in other tombs,[29] the foregoing parallels (even cross-subject) suffice to verify the Zhuozhou artisans’ reference to preexistent templates such as sketchbooks.[30] The regional homogeneity among filial piety images across north China suggests that sketchbooks or mnemonics for tomb paintings had been transmitted among artisan groups in certain locales, such as Yan Prefecture (present-day Beijing and northern Hebei) and the region covering present-day southern Shanxi and northern Henan.

Figure 6. The story of Zhao Xiao (center), Yuan dynasty. Northern wall of the Zhaitang tomb, Beijing. From Zhongguo meishu quanji: mushi bihua, 166–67.

Figure 7. The story of Zhao Xiao, Jin Dynasty. Western wall of the Tunliu Songcun tomb, Shanxi. From Zhu et al., “Shanxi Tunliu Songcun,” 60.

In a modular system, a term first applied to Chinese art by Lothar Ledderose, the continuity of modules such as visual details and the overall mise-en-scène of a narrative episode coexists with the possibility of new assemblage.[31] Such a system effectually allows artisans a considerable degree of compositional autonomy without forsaking the pictorial traditions of each filial piety story. Almost no other coeval images of filial piety were found to incorporate such a vast number of independent stories into one structural whole as the two Zhuozhou murals,[32] and the enclosing landscapes—rocks, trees, and mountain ranges—function as a compositional device to divide each tale. Eugene Wang proposes two kinds of sentiments that natural backgrounds arouse: early images of landscapes symbolize a supernatural otherworld, while the landscapes of the Song–Yuan periods are more or less mixed with a pastoral ideal.[33] The landscape element at Zhuozhou tomb would have alluded to the latter sentiment in response to the prevalence of landscape paintings of this time, in which natural scenes served as “a moral corrective for” kaleidoscopic urban degradations.[34] Arguably certain landscape motifs that had gained unprecedented currency in the Yuan period entered artisans’ pictorial repertoire, and were easily deployed with other motifs in combinations seldom seen in earlier times, including the filial piety story.

The compositional innovation of the Zhuozhou tomb artisans came with a price. The torsos of some figures are disproportionate, and discernible traces of the initial draft suggest that artisans drafted and finalized two paintings directly on the walls.[35] This unskillfulness is in sharp contrast with the dexterity manifested in the set images of servants. Perhaps the artisans did not have a readily available preparatory sketch for the complete composition of multiple filial piety stories; the only obtainable sketchbooks for this subject matter were monoscenic. Why, then, were the images of filial sons worth the toil of changing the conventional monoscenic formula? Zheng Yimo and Wang Lili conclude that the families of the deceased thought highly of the murals because of the artisans’ creativity.[36] I contend that the reality was the other way around. In the historical context of workshop practice in Yuan period north China,[37] tomb-building had become highly standardized,[38] and only special demand from the clientele would have incentivized artisans in Zhuozhou to create something new.

The evidence available to date does not provide a definite account of the client’s demand, but the epitaph allows rough speculation:

[Li Yi, the tomb occupant] originally served as a Confucian clerk (ruli) in the government, and was promoted to the magistrate of Fengrun County. . . . Yi dedicated himself to improving welfare, cultivating virtue, and humanizing the people. He never engaged in malfeasance . . . This mourning hall is about twenty chi in depth. When the murals were being painted, the walls were wet with dew because of poor ventilation. After Bingyi [the eldest son of Li Yi] prayed in four directions, wind started to blow into it. The paintings were aided by Heaven, and future generations must not destroy them.[39]

The unusual latter half of the otherwise formulaic epitaph quoted above shows that the murals were important to Li Yi’s descendants. The implicit motivation that drove the Li family to connect the murals of the tomb to sacrality possibly related to the self-identity of the Li family. Yi initiated his career as a “Confucian” clerk, and was once appointed fupan of the Dadu Route (Dadulu).[40] Imperial examination had not been held for decades under Mongolian rule, and the selection of higher-ranking officials was largely based on family background;[41] the local administration then had to widely employ clerks (li), many of whom later advanced into official bureaucrats.[42] According to the epitaph, Li presumably entered officialdom following the same route. Interestingly, the text emphasizes the family’s identification with Confucian values: Yi is described as a man who earnestly “cultivat[ed] virtue and humaniz[ed] the people”; he also named his sons using characters that denote royalty, justice, and propriety—all virtues encouraged in Confucianism. Of course, some of the phrases were not uncommon in the epitaphs of the period. It is useful to note, however, that most of these epitaphs belonged to the official-scholars (shi), whereas almost all of the decorated tombs excavated belonged to non-literati who neither held office nor pursued scholarly endeavor, and usually did not contain epitaphs.[43] In this sense, the Zhuozhou tomb stands out from the rest of the decorated tombs in north China. The unusual investment of Yi’s offspring in Confucian values seems to underscore that Yi was different from the petty clerks disparaged by formal officials, so as to play down his ambiguous identity.[44] It is hence comprehensible that his sons were willing to sponsor artisans to embellish his eternal underground residence with images of filial piety that exceed the pictorial conventions, symbolically assuming their father’s mantle as a paragon of Confucian morality.[45]

Local Kinship Groups: Tunliu Tomb in Shanxi

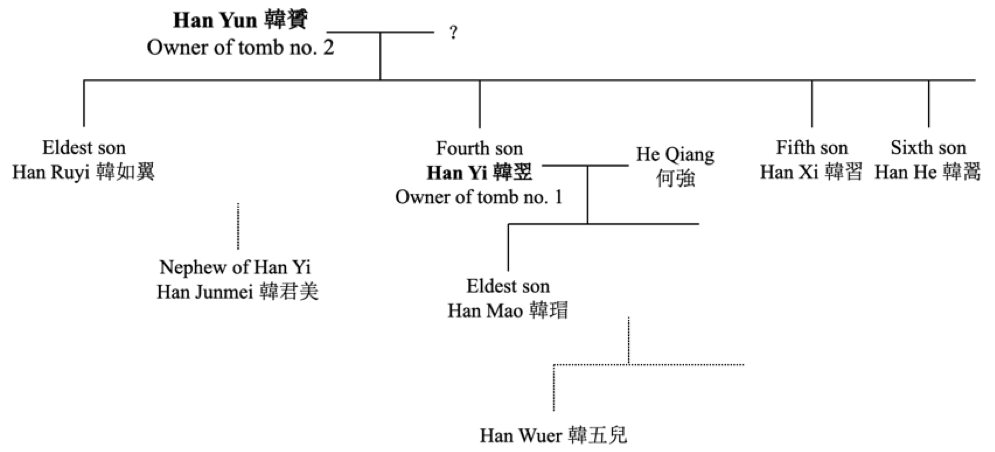

Two Yuan period tombs excavated in Tunliu County, Shanxi Province, belong to the local Han family.[46] Fig. 8 diagrams a brief genealogy of its three generations. Han Yi, the male occupant of Tomb no. 1 (constructed in 1306), was the fourth son of Han Yun, the owner of Tomb no. 2 (built in 1276). Images of filial piety stories occupy central positions in the pictorial programs of both tombs: each wall of Han Yi’s tomb has one false door and two false windows, with paintings of filial sons ornamenting their intervals; the four paintings of filial sons at Han Yun’s tomb spread across the entire plane of three walls.

Figure 8. Patrilineal kinship relationship of the Han family, Tunliu, Shanxi. Created by the author.

Figure 9A, 9B. Two images of filial piety story (the story of Yang Xiang on the left, story unknown on the right), 1306 CE. Northern wall of Han Yi’s tomb, Tunliu, Shanxi. From Yang et al., “Shanxi Tunliu,” plate 9, figs. 2, 3.

Figure 9A, 9B. Two images of filial piety story (the story of Yang Xiang on the left, story unknown on the right), 1306 CE. Northern wall of Han Yi’s tomb, Tunliu, Shanxi. From Yang et al., “Shanxi Tunliu,” plate 9, figs. 2, 3.

These tombs are surviving examples that elucidate the Yuan period’s turn towards “ornamentation” in tomb construction.[47] The tomb of Han Yi exemplifies one facet of this turn: the visual symmetry of murals. The image of Yang Xiang, a female figure in the Twenty-four Paragons, fighting a tiger was made spatially symmetrical with another unidentified image on the northern wall (Fig. 9A, 9B). Assuredly, this image of a dragon-slaying woman cannot be attributed to any known tale of filial piety, but its formal parallel with the image of Yang Xiang is revealing: both delineate the scene of a valiant woman grappling with a ferocious beast, and the clothing is also identical. On the eastern wall, the four prominent images of filial sons are also rendered visually symmetrical. The settings of two images in the center (Figs. 10A and 10B) are balustraded terraces with foggy mountains at a distance; characters in the other two images on the margins are foregrounded by pine trees and craggy stones alike.

Figure 10A, 10B. Two images of filial piety story, 1306 CE. Eastern wall of Han Yi’s tomb, Tunliu, Shanxi. From Yang et al., “Shanxi Tunliu,” plate 9, fig. 4, and plate 10, fig. 3.

Figure 10A, 10B. Two images of filial piety story, 1306 CE. Eastern wall of Han Yi’s tomb, Tunliu, Shanxi. From Yang et al., “Shanxi Tunliu,” plate 9, fig. 4, and plate 10, fig. 3.

That wall paintings are presented in the form of interior decoration—for example, a screen or a hanging scroll—is another feature of the tendency toward ornamentation. All the paintings at Han Yun’s tomb are displayed as if they were disclosed under rolled-up draperies in a living room. Black strips frame the images of filial sons to reproduce the wooden columns of a standing screen; two decorative ribbons attached to the top of each alternatively suggest the special mounting components (jingyan) of Chinese hanging scrolls (Fig. 11). Such a treatment is epitomized in the Hongyucun tomb in Shanxi, built nearly thirty years later. In that tomb, images of servants and filial piety stories are framed into screens and scrolls (Fig. 12), eternally frozen under the Yellow Spring.[48]

The tomb’s design devices of symmetry and picture-framing possibly corresponded to the aboveground ritual space.[49] Inscriptions such as “here in this position (ciwei) stands XXX [characters missing], the fifth son of Han Yun” and “here in the center of this position stands Han Ruyi (the eldest son)” on the murals of the eastern and the western walls of Han Yun’s tomb signify the offspring, who are supposed to be reverently standing in assigned positions in tribute to a long inscription about Han Yun written on the northern wall. Such a virtual positioning of family members was also present in traditional funeral rites.[50] The images shown beside the inscriptions, however, are not specific portraits of Han Yun’s children but idealized images of filial sons and attendants. More intriguingly, while other images of filial sons bear no cartouches to indicate their names, the image of Han Boyu has an accompanying inscription— “here in this place (cichu) is Han Boyu.”[51] Tomb painters deliberately wrote down the name of Han Boyu, who shares the surname with the tomb occupant (and his descendants), as if this prominent filial paragon from the past, transcending his historical specificity,[52] were a member of the Han family. The filial descendants of Han Yun in this way became comparable to Han Boyu, perpetually serving their forebears underground.[53] In addition, evidence also suggests the real presence of family members in the graveyard. Since Song, people had established a custom of visiting tombs and holding banquets on fixed days.[54] Additionally, the tombs discussed here are husband-wife joint tombs, whose chambers, according to documented dates, were opened multiple times for burial. On whichever occasion, the tomb could have been turned into a locus that might have functioned temporarily as an ancestral hall.[55]

Figure 11. Black wooden frame and hanging ribbons of filial piety images, 1276 CE. The southeastern corner of Han Yun’s tomb, Tunliu, Shanxi. From Yang et al., “Shanxi Tunliu,” plate 16, fig. 3.

This appropriation of family ritual space relates closely to the clients’ aspiration to bless the progeny, an aim shared extensively by local kinship groups. The tomb inscriptions mark an expectation of family prosperity. For example, Han Yi’s tomb inscription ends with a blissful invocation: “After building the tomb, may my sons and grandsons enter officialdom, and may the entire family flourish year by year.” These formulaic supplications make us wonder whether the association of tomb construction with family welfare was merely wishful thinking, or whether the act of building a tomb indeed tangibly benefited the family. The reality was more likely to be the latter. First, tomb sites were a locus for achieving family cohesion. The gathered family members, either physically in situ or virtually in the “position,” could reinforce their identification with the kinship group. Second, tomb-building afforded an opportune time for the family to collect and organize its genealogy. Han Yun’s sons and grandsons were named in a systematic way to embody a rigorous order of seniority (see Fig. 8)—a well-devised tactic to regulate a large household. Third, the process of tomb construction itself was an event that enabled and enacted social connections. Multiple participants from the vicinity partook in this activity, including two mason brothers working in tandem, a painter named Han Junmei (a nephew of Han Yi), an elegy writer, and two diviners. These people all came from nearby villages; the epitaph that excessively complimented the tomb occupant and his offspring was written by someone of good repute from the local community. Although Han Yi never served as an official, he was elected the Community Head (shezhang) to manage affairs such as irrigation, elementary schooling, and the maintenance of social order.[56] These non-literati local leaders, who would be in charge of orchestrating temple fairs and other commercial events in mercantile regions, extremely valued their standing in the neighborhood.[57] The brief inscriptions on the wall evince that the preparatory work for building a tomb was not an effortless task, but rather a good opportunity for local leaders such as Han Yi to confirm and strengthen their community networks.

Figure 12. Images of filial piety and wine preparation, 1309 CE. Southern wall of the Hongyucun tomb, Shanxi. From Han and Huo, “Hongyucun,” 42, fig. 5.

Parallel to the influence of ritual space, some decorative elements from living quarters that reflect the aesthetic predilection of tomb occupants were efficaciously appropriated and assimilated into the burial chamber.[58] Architectural units were often designated with name plaques below the cornice, such as “Pavilion of Upright Virtues” and “Pavilion of Chrysanthemum,” a practice that resonates with the literati custom of giving garden sites names of refined taste and virtue since the Song period.[59] In addition, the paintings of Han Yun’s tomb consciously imitate the hanging scrolls and standing screens that were common in the coeval décor of the affluent.[60] Its images of filial piety (Fig. 13), teeming with intellectual finesse, are on par with the sophisticated landscape paintings of the Yuan Dynasty. Its bland hue, stone texturing, and poised combination of the landscape setting and the colophon all evoke the coloring, technique, and composition of literati paintings.

Consequently, the social dimension of interior furnishing would also extend to the tomb context. Jonathan Hay perceptively points out that decoration as luxury reinforced the owner’s social status, and through decoration arrivistes acquired cultural capital in a tangible form.[61] James Cahill links the popularity of landscape painting in the Yuan period to the identity criteria of the literati: the pre-Yuan intellectuals viewed literacy in classics and poetry as the threshold for identity, whereas the literati of Yuan embraced landscape painting as part of that standard, and connoisseurs enjoyed the same social status as amateur painters did.[62] Han Yun and Han Yi were certainly not members of the literati, but when they decorated their living rooms with exquisite hanging scrolls, they implicitly transmuted certain cultural assets that were exclusive to the literati into the authority of their family. The Southern Song social transformation of the shi scholars into local elites who purchased land locally as their property base provided a justifiable cause for the affluent landed gentry (the Han family owned dozens of hectares of land) to adopt the decorum of the intellectuals in reverse.[63] In conclusion, the images of filial piety stories against an artistic landscape setting in these tombs tangibly addressed Han’s petition to family solidarity, on the one hand; and the images, on the other hand, solidified the family’s position in the local community by demonstrating its “elevated” taste.

Figure 13. Story of Wang Xiang, 1276 CE. Northern wall of Han Yun’s tomb, Tunliu, Shanxi. From Yang et al., “Shanxi Tunliu,” plate 15, fig. 1.

Conclusion

Although different in certain respects, these “new” images of filial sons, which became one of the most arresting motifs in some Yuan period tombs in north China, demonstrate some similarity in both content and form. In their content, they drew from a more miscellaneous pool of filial piety stories and variants, many of which were not documented in the extant textual sources of the Song–Yuan periods; meanwhile, they often featured landscape elements as background. In terms of form, the paintings grew larger over the time, and sporadically synthesized multiple stories into one composition; they were relocated from originally unnoticeable nooks to the center of display.

While it is facile to summarize such features, it is less easy to articulate historically anchored and socioculturally informed explanations for their emergence. I treat the images of filial sons from the three tombs as respective points of departure, attempting to correlate this historical transition with the agency of particular tomb artisans and their clients. Directly executing the adornment, these artisans on the one hand capitalized on the flexibility granted by modular design and the preexistent repertory of painting manuals bequeathed from the Song–Jin periods. On the other hand, they were always inspired by the tantalizing new trends in the textual, publishing, and theatrical domains that grew more palpable in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century China. The tomb occupants discussed in this paper fall roughly into the non-literati elite class on the social hierarchy—wealthy landlords or merchants, and occasionally clerk-officials who served in minor positions. They or their family members, out of eagerness to maintain family solidarity and social repute, opted for this new type of filial piety images. When acting as “Confucian clerks” or “Community Heads” within the local nexus, they were incentivized by the promise of public recognition and managerial authority, and fervently aspired to display their outstanding moral fiber as well as aesthetic taste.

The examples discussed here admittedly amount to no more than the tip of an iceberg within the expansive region of northern China, and more Yuan period tombs that have plain or even no images of filial piety fall outside the purview of this study. The three case studies by no means provide, nor do I intend, an inclusive account of the continuities and metamorphoses in the mortuary practice of the Yuan period northern China. These images, however, do provide traceable evidence for us to partially understand the complicated interactions between artisans and their clients through the prism of silent pictures and fragmented words preserved underground.

Endnotes

[1] For the archaeological report, see Xu Haifeng et al., “Hebei Zhuozhou Yuandai bihuamu,” Wenwu, no. 3 (2004): 42–60.

[2] Scholars have proposed different interpretations of the meaning and function of such images. They might have been related to the attainment of immortality, the display of the offspring’s filial piety, and the spiritual resonance of filially pious deeds; see He Xilin, “Beichao huaxiangshi zangju de faxian yu yanjiu,” in Hantang zhijian de shijuewenhua yu wuzhiwenhua, ed. Wu Hung (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2003), 341–73; Zou Qingquan, Xingwei shifan: Beiwei xiaozi huaxiang yanjiu (Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 2015), 205–11; Eugene Wang, “Coffins and Confucianism: The Northern Wei (386–534) Sarcophagus at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts,” Orientations, no. 30 (1999): 56–64; Lin, Sheng-Chih, “Hokuchō jidai ni okeru sōgu no zuzō to kinō: sekkan yuka ibyō no hakashu shōzō to Kōshidenzu o rei toshite,” Bijutsushi 154 (2003): 207–26.

[3] This era witnessed a unique category of tomb built in brick like a building and decorated with reliefs and paintings; see Wei-Cheng Lin, “Underground Wooden Architecture in Brick: A Changed Perspective from Life to Death in 10th- through 13th-Century Northern China,” Archives of Asian Art 61, no. 1 (2011): 3–4. The majority of these tombs belonged to non-literati local elite in north China; see Jeehee Hong, “Changing Roles of the Tomb Portrait: Burial Practices and Ancestral Worship of the Non-literati Elite in North China (1000–1400),” Journal of Song–Yuan Studies 44 (2014): 208–11. On the issue of the ethnicity of these tomb occupants in the Yuan period, see Nancy Steinhardt, “Yuan Period Tombs and Their Inscriptions: Changing Identities for the Chinese Afterlife,” Ars Orientalis 37 (2009): 140–74.

[4] The iconographic discussion of “The Twenty-four Paragons” includes the following: on its formation, Zhao Chao, “Ershisixiao zai heshi xingcheng,” Zhongguo dianji yu wenhua, nos. 1 and 2 (1988): 50–55 and 40–45; on the surviving northern version of “The Twenty-four Paragons,” see Dong Xinlin, “Beisong Jin Yuan muzang bishi suojian Ershisi xiao gushi yu Gaoli Xiaoxinglu,” Huaxia kaogu, no. 2 (2009): 141–52; on its social implications, see Keith Knapp, Selfless Offspring: Filial Children and Social Order in Medieval China (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2005), 113–63; for its spread in the mainland and the East Asian world, see Uno Mizuki, Kō no fūkē: setsuwa hyōshō bunkaron josetsu (Tokyo: Bensei shuppan, 2016), 133–196 and 445–552. The functions of such images in Song, Jin, and Yuan were understood under the framework of ethnic interactions and religious conceptions; see Zou Qingquan, “Sanjiao yuanrong yujing zhong de Yuandai muzang yishu,” Meishu yu sheji, no. 2 (2014): 76–81; Deng Fei, “Guanyu Song Jin muzang zhong xiaoxingtu de sikao,” Zhongyuan wenwu, no. 4 (2009): 75–81; Guo Dongsheng and Xue Lulu, “Cong Liaomu Ershisixiao huaixangshi guankui rujia sixiang dui Liao qidan wenhua de yingxiang,” in Liaojin lishi yu kaogu guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji, ed. Liu Ning and Zhang Li (Shenyang: Liaoning jiaoyu chubanshe, 2012), 71–76; Dong Xinlin, “Beifang diqu Mengyuan muzang chutan,” Kaogu, no. 9 (2015): 114–120.

[5] Liu Yingchun et al., “Henan Weishixian Zhangshizhen Songmu fajue jianbao,” Huaxia kaogu, no. 3 (2006): 13–18.

[6] Li Fang, Taiping yulan (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1960), 1899.

[7] Accurate dating of this script, entitled “The Tale of Dong Yong Encountering a Fairy,” is uncertain, but its linguistic features evince that it is a storytelling script from the Song–Yuan periods; see Hong Pian, Qingpingshantang huaben (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2012), 377–78; Chang Jinlian, Liushijia xiaoshuo yanjiu (Jinan: Qilu shushe, 2008), 121–22.

[8] Hong, Qingpingshantang, 369–70.

[9] See Li Quanshe, “Shanxi Wenxi Sidi Jinmu,” Wenwu, no. 7 (1988): 73.

[10] Fenlei hebi tuxiang jujie juncheng gushi, Gozan reprint of the Yuan woodblock printing. Collection of Tōyō Bunko, Tokyo. Quoted in Uno, Kō no fūkē, 673.

[11] Tang Xianzu, Xinbian xiuxiang nankeji, Wujun shuyetang edition, plate 1. Collection of the National Central Library, Taipei.

[12] Dong Xinlin, “Gaoli Xiaoxinglu,” 141–52; Osawa Akihiro, “Mingdai chuban wenhua zhong de Ershisixiao: lun xiaozi xingxiang de jianli yu fazhan,” Mingdai yanjiu tongxun, no. 5 (2002): 11–33. For the divide between the north and the south during the Song–Jin periods, see Tao Jinsheng, Nüzhen shilun (Taipei: Shihuo yuekan chubanshe, 1981), 122–128.

[13] The image of Jiaohuanü in this tomb exemplifies this change; see Liu Wei, “Weishi Yuandai bihuamu zhaji,” Gugong bowuyuan yuankan, no. 3 (2007): 48–52; see also Osawa Akihiro, “Mingdai chuban wenhua zhong de Ershisixiao,” 11–33.

[14] For an overview of the exchange, see Hsiao Ch’i-ch’ing, “Yuanchao de tongyi yu tonghe: yi handi Jiangnan wei zhongxin,” in Nei beiguo er wai zhongguo (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2007), 26–29.

[15] Mural artisans would usually incorporate what they learned from the local, visual culture that surrounded them. See Paul R. Katz, Images of the Immortal: the Cult of Lü Dongbin at the Palace of Eternal Joy (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1999), 141; Anning Jing, The Water God’s Temple of the Guangsheng Monastery: Cosmic Function of Art, Ritual, and Theater (Leiden: Brill, 2002): 63.

[16] Guan Yunshi, Xinkan quanxiang chengzhai xiaojing zhijie (Beijing: Laixunge shudian, 1938), 15.

[17] Guan, preface.

[18] For the study of this hand scroll, see Richard Barnhart, Li Kung-lin’s Classic of Filial Piety (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993), 73–155.

[19] Stage performance might have served as a source of inspiration for artisans who made nianhua or zhima in Late Imperial China. See Bo Songnian, Zhongguo nianhua shi (Shenyang: Liaoning meishu chubanshe, 1986), 84–86. Katz proposed that performers could have also learned from temple art. See Katz, Images of the Immortal, 140.

[20] Despite a relative recession afterwards, this zaju tradition was again revitalized in the Yuan period. Many famous dramatists recorded in Luguibu came from this region; see Liao Ben, Song Yuan xiqu wenwu yu minsu (Beijing: Wenhua yishu chubanshe, 1989), 257.

[21] For a systematic catalog, see Liao, 137–246; Che Wenming, Ershi shiji xiqu wenwu de faxian yu quxue yanjiu (Beijing: Wenhua yishu chubanshe, 2001), 12–21. For a discussion of some newly found materials, see Deng Fei, “Song Jin shiqi zhuandiao bihuamu de tuxiang ticai tanxi,” Meishu yanjiu, no. 3 (2011): 74–80.

[22] For these entries, see Zhong Sicheng, Jia Zhongming, and Pu Hanming, Xinjiao Luguibu zhengxubian (Chengdu: Bashu shushe, 1996), 71, 145, 166. Complete scripts for most of these plays did not survive. For one extant example, see Wang et al., eds., Quanyuan xiqu vol. 2 (Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1999), 588–607.

[23] Zhongguo guisuanyan xiehui, Zhongguo taoci shi (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 1982), 351; Ma, Zhongguo qinghuaci (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1999), 49.

[24] The sarcophagus belongs to an early Yuan Daoist Pan Dechong. Scholars are still in disagreement regarding this second-floor stage. Xu Pingfang believes that the Yuan period wuting was on the second floor, as was the case in shanmen stages of monasteries; see Xu Pingfang, “Guanyu Songdefang he Pandechong mu de jige wenti,” Kaogu, no. 8 (1960): 44. Liao Ben, on the other hand, notes that this type of building was not specially designed for performance, and most surviving stages from Yuan Dynasty are one-story; see Liao Ben, “Song Yuan xitai yiji: Zhongguo gudai juchang wenwu yanjiu zhiyi,” Wenwu, no. 7 (1989): 88–95. Jeehee Hong is inclined to believe that both types of stage existed in Song and Yuan times; see Jeehee Hong, “Virtual Theater of the Dead: Actor Figurines and Their Stage in Houma Tomb No. 1, Shanxi Province,” Artibus Asiae 71 (2011): 106–109.

[25] Katz, Images of the Immortal, 134.

[26] Wu Hung, Space in Art History, trans. Qian Wenyi (Beijing: Horizon Books, 2018), 240. For examples of filial piety images, see Deng Fei, “Tuxiang de duochong yuyi: zailun Song Jin sangzang yishu zhong de xiaozitu,” Yishu tansuo, no. 6 (2017): 52.

[27] Yuan Hong, Houhan ji (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2002), 171.

[28] For this cross-subject comparison, see Zhao Dankun, “Beifang Mengyuan muzang muzhuren xingxiang yu zushu wenti de zaisikao,” Zhongyuan wenwu, no. 1 (2017): 80. A Buddhist divine guardian stands in a similar posture on a frontispiece printed in Khitan Liao from the same region; see Shih-shan Susan Huang, “Reassessing Printed Buddhist Frontispieces from Xi Xia,” Zhejiang University Journal of Art and Archaeology 1, (2014): 149.

[29] Archaeologists have, however, come across identical images on brick reliefs found from tombs in nearby regions; see Deng Fei, “Modular Design of Tombs in Song and Jin North China,” in Visual and Material Cultures in Middle Period China, ed. Patricia Ebrey and Shih-shan Huang (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2017), 42–45.

[30] For the use of sketchbooks, or fenben, see Katz, Images of the Immortal, 140–141; James Cahill, The Painter’s Practice: How Artists Lived and Worked in Traditional China (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 88–112; Shih-shan Susan Huang, Picturing the True Form: Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2012), 285–90.

[31] Lothar Ledderose uses the term “module” to refer to standardized, prefabricated parts that could be put together quickly in different combinations, creating an extensive variety of units from a limited repertoire of components; see Ledderose, Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 1 and chap. 7. Another relevant concept in Chinese is getao, which has a standard composition of certain narratives to ensure readability; see Hsing I-tien, “Getao, bangti, wenxian yu huaxiang jieshi,” in Huaweixinsheng (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2011), 119–120. For a study of modular motifs in Buddhist frontispiece prints, see Shih-shan Susan Huang, “Media Transfer and Modular Construction: The Printing of Lotus Sutra Frontispieces in Song China,” Ars Orientalis 41 (2011): 140–52.

[32] Nearly all images of filial sons of Song–Jin tombs are monoscenic, with very few exceptions, such as the Renhou tomb in Yiyang and the Pingmo tomb in Xinmi. These two examples, however, contain many fewer integrated stories than the Zhuozhou tomb. Framing filial piety stories with landscape was a common practice on sarcophagi nearly one millennium earlier, but it is not very likely that tomb artisans in the Yuan period knew these materials.

[33] Eugene Wang, Shaping the Lotus Sutra: Buddhist Visual Culture in Medieval China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005), 183.

[34] Wang, 183.

[35] For the lines and brushstrokes of the preliminary draft in these two paintings, see Hao Jianwen, “Zoujin shenmi de Hebei muzang bihua ba: Zhuozhou Yuandai bihua mu,” Dangdairen, no. 3 (2010): 31–33.

[36] Zheng Yimo and Wang Lili, “Hebei Zhuozhou Yuanmu bihua yanjiu,” Nanjing yishu xueyuan xuebao, no. 5 (2015): 55.

[37] For the operating model and commercial competition of tomb constructions, see Li Qingquan, “Fenben: cong Xuanhua Liaomu bihua kan gudai huagong de gongzuo moshi,” Nanjing yishu xueyuan xuebao, no. 1 (2004): 36–39; Deng, “Modular Design,” 52–72. There was a similar interaction between workshop artisans and their monastic patrons in the case of mural paintings at Buddhist and Daoist temples during the Yuan period in southern Shanxi. See Nancy S. Steinhardt, “Zhu Haogu Reconsidered: A New Date for the ROM Painting and the Southern Shanxi Buddhist-Daoist Style,” Artibus Asiae 48, no. 1/2 (1987): 5–38; Katz, Images of the Immortal, 134–142.

[38] The standard procedure for tomb construction at this time consisted of three steps: masons erected walls before carvers and painters worked consecutively; finally scribes, if needed, were invited to write inscriptions. See Deng, “Modular Design,” 52–64.

[39] Xu et al., “Hebei Zhuozhou,” 59.

[40] This official title referred to the administrative assistant to the governor of the Superior Prefecture in which the dynastic capital was located; see Charles O. Hucker, A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China, Taiwan Edition (Taipei: Southern Materials Center, 1987), 219, entry 2089.

[41] Hsiao Ch’i-ch’ing, “Mengyuan zhipei dui Zhongguo lishi wenhua de yingxiang,” in Nei beiguo er wai zhongguo, 56.

[42] For the reliance of Yuan local administration on clerks, see Elizabeth Endicott-West, Mongolian Rule in China: Local Administration in the Yuan Dynasty (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1989), 105–110. For the special status of clerks during the Yuan Dynasty, see Zhu Zongbin, Zhongguo gudai zhengzhi zhidu yanjiu (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 2006), 60–144.

[43] Dieter Kuhn, “Decoding Tombs of the Song Elite,” in Burial in Song China, ed. Kuhn (Heidelberg: Edition Forum, 1994), 11–12; Hong, “Changing Roles,” 209–210.

[44] Despite the rising status of clerks in Yuan, contemporary intellectuals still excoriated or even vilified them; see examples in Endicott-West, Mongolian Rule in China, 106–109.

[45] For the agency of the descendants in constructing Zhuozhou tomb, see Lin Wei-Cheng, “Shilun ‘mushi jianzhu kongjian’: cong shijuexing dao wuzhixing de lishi fazhan,” in Gudai muzang meishu yanjiu disiji, ed. Wu Hung, Zhu Qingsheng, and Zheng Yan (Changsha: Hunan meishu chubanshe, 2017), 44–49.

[46] Unless noted, information about these two tombs has been retrieved from their archaeological report; see Yang Linzhong et al. “Shanxi Tunliuxian Kangzhuang gongye yuanqu Yuandai bihuamu,” Kaogu, no. 12 (2009): 39–46.

[47] Wang Yudong, “Mengyuan shiqi mushi de ‘zhuangshihua’ qushi yu Zhongguo gudai bihua de shuailuo,” Meishu xuebao, no. 4 (2012): 27–30.

[48] Han Binghua, and Baoqiang Huo, “Shanxi Xingxian Hongyucun Yuan zhida ernian bihuamu,” Wenwu, no. 2 (2011): 40–46; Zheng Yan, “Xiyang xixia: du Xingxian Hongyucun Yuandai Wuqing fufumu bihua zhaji,” in Gudai muzang meishu yanjiu disanji, ed. Wu Hung, Zhu Qingsheng, and Zheng Yan (Changsha: Hunan meishu chubanshe, 2015), 266–68.

[49] Such as the family image hall (yingtang); see Li Qingquan, “ ‘Yitangjiaqing’ de xinyixiang: Song Jin shiqi de muzhu fufuxiang yu Tangsong muzang fengqi zhibian,” Meishu xuebao, no. 4 (2013): 18–30; Yi Qing, “Song Jin Zhongyuan diqu bihuamu ‘muzhuren dui (bing) zuo’ tuxiang tanxi,” Zhongyuan wenwu, no. 2 (2011): 77–78. For a discussion of the relationship between yingtang and tomb portrait, see Hong, “Changing Roles,” 212–50.

[50] Sima Guang, Simashi shuyi (Taipei: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1983–1986), 504. Ironically, Sima denounced such tombs of landlords and merchants as vulgar and opulent; see Wu Hung, The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs (London: Reaktion Books, 2010), 82–83.

[51] The story of Han Boyu is one of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety.

[52] For the temporality embedded in filial son images, see Wu, Art of the Yellow Springs, 180–82.

[53] Yuan Quan also suggests the tomb chamber as the space for eternal worship; see Yuan Quan, “Cong muzang zhong de ‘chajiu ticai’ kan Yuandai sangzang wenhua,” Bianjiang kaogu yanjiu, no. 6 (2007): 329–49.

[54] Patricia Ebrey, “The Early Stages in the Development of Descent Group Organization,” in Kinship Organization in Late Imperial China, 1000–1940, ed. Ebrey and James Watson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 20–29.

[55] The ancestral hall of those non-office-holding people was not mentioned in historical sources until the Yuan period. In Song, most ancestral shrines belonged to high-ranking officials, or were sponsored by local communities as memorials to individuals of outstanding contributions; see Ebrey, “Development of Descent Group Organization,” 51–53. See also Lin, “Mushi jianzhu kongjian,” 45.

[56] For the scope of the Community Head’s power, see Endicott-West, Mongolian Rule in China, 119–121; Hucker, A Dictionary of Official Titles, 65.

[57] Zhao Shiyu, “Mingqing shiqi Huabei miaohui yanjiu,” Lishi yanjiu, no. 5 (1992): 126–27.

[58] For a discussion of appropriation rather than mere imitation, see Lin, “Underground Wooden Architecture,” 5.

[59] Robert E. Harrist, Jr., “Site Names and Their Meanings in the Garden of Solitary Enjoyment,” The Journal of Garden History 13 (1993): 199–212; John Makeham, “The Confucian Role of Names in Traditional Chinese Gardens,” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 18 (1998): 187–210.

[60] Michael Sullivan, “Notes on Early Chinese Screen Painting,” Artibus Asiae 27 (1965): 248–254.

[61] Jonathan Hay, Sensuous Surfaces: The Decorative Object in Early Modern China (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2010), 21–23; Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 9–63.

[62] James Cahill, Hills Beyond a River: Chinese Painting of the Yuan Dynasty, 1279–1368 (New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1976), 4–5.

[63] Peter Bol, “This Culture of Ours”: Intellectual Transitions in T’ang and Sung China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992), 71–75. Intellectuals in the Yuan period continued with this practice; see Hsiao, “Mengyuan zhipei,” 47.

Glossary

| chi 尺 | getao 格套 | Hebei 河北 | jingyan 驚燕 | Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) 北宋 | shi 士 | yingtang 影堂 |

| cichu 此處 | Guan Yunshi 貫雲石 | Henan 河南 | Li Bingyi 李秉彝 | Pingmo 平陌 | Tang dynasty (618–907) 唐代 | Yiyang 宜陽 |

| ciwei 此位 | Han Boyu 韓伯瑜 | Hong Pian 洪楩 | Li Gonglin 李公麟 | Renhou 仁厚 | Tunliu 屯留 | zaju 雜劇 |

| Dadulu 大都路 | Han Junmei 韓君美 | Hongyucun 紅峪村 | Li Yi 李儀 | ruli 儒吏 | Weishi 尉氏 | (Zhao) Li 趙禮 |

| Dong Yong 董永 | Han Ruyi 韓如翼 | huaishu 槐樹 | li 吏 | shanmen 山門 | wuting 舞廳 | Zhao Xiao 趙孝 |

| fenben 粉本 | Han Yi 韓翌 | Jiaohuanü 焦花女 | Liao dynasty (915–1125) 遼代 | Shanxi 山西 | Xinmi 新密 | Zhuozhou 涿州 |

| fupan 府判 | Han Yun 韓贇 | Jin dynasty (1115–1234) 金代 | Luguibu 錄鬼簿 | shezhang 社長 | Yang Xiang 楊香 | Meng Zong 孟宗 |

Table 1

Yuan Period Tombs with Images of Filial Piety

| Pro-vince | Tomb | Period | Tomb owner | Structure | Location of filial piety images | Description of filial piety images | Source |

| Inner Mon-golia | Liangcheng County Houdesheng no.1 tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Square, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Central register of the eastern and western walls | Rectangular composition; without clear boundaries between story units; decorated with mountains and trees; framed in black strips | Wenwu, no. 10 (1994): 10–18. |

| Hebei | Zhuozhou tomb | 1339 CE | Li Yi and his wife Fang | Octagonal, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Southeastern and southwestern walls | Multiple stories conflated into one composition; every story unit separated by mountain ranges; clear traces from previous drafts | Wenwu, no. 3 (2004): 42–60. |

| Hebei | Beijing Zhaitang tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Square, single-chamber, brick architecture | Western wall | Three stories conflated into one composition, and separated by trees; decorated with hills, rivers, and clouds | Wenwu, no. 7 (1980): 23–26. |

| Hebei | Xingtai Iron & Steel Corp. no. 1 tomb | Later period of Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Round, single-chamber | Northern side of the false door on western wall; southern and northern sides of the false door on eastern wall | Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; simple setting in accordance with the plot | Kaogu yu wenwu, no. 4 (2008): 28–33. |

| Henan | Luoyang suburb tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Hexagonal, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Painted bricks in the niches on each wall | Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; perfunctorily decorated with stones and trees | Wenwu camkao ziliao, no. 1 (1958): 56–59. |

| Henan | Weishi County Zhangshi tomb | Later period of Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Rectangular, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Above the portraits of tomb occupants on northern wall; northern sides of eastern and western walls | Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; considerably complex setting

|

Huaxia kaogu, no. 3 (2006): 13–18. |

| Shanxi | Ruicheng Pan Dechong sarcophagus | c. 1260 CE | Pan De-chong (Daoist) | Sarcophagus | Two side panels

|

Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; simple setting in accordance with the plot; each composition separated by cartouche and space | Kaogu, no. 8 (1960): 22–28. |

| Shanxi | Tunliu County Kangzhuang Industrial Area no. 2 tomb | 1276 CE | Han Yun and his wife | Square, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Northern wall; northern sides of eastern and western walls | Large monoscenic composition; all decorated with finely executed natural scenes; long inscriptions on the painting; framed in black strips | Kaogu, no. 12 (2009): 39–46. |

| Shanxi | Tunliu County Kangzhuang Industrial Area no. 1 tomb | 1306 CE | Han Yi and his wife He | Square, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Both sides of the false window on northern wall; eastern and western walls | Monoscenic composition; mountains and trees in the background | Kaogu, no. 12 (2009): 39–46. |

| Shanxi | Changzhi Zhuoma no. 2 tomb | 1307 CE | Yang Cheng and his wife Shen | Square, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Northern wall; northern side of eastern and western walls | Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; simple setting in accordance with the plot; framed in red strips | Wenwu, no. 6 (1985): 65–72. |

| Shanxi | Xing County Hongyucun tomb | 1309 CE | Wu Qing and his wife Jing | Octagonal, single-chamber, masonry architecture | Southern and northern walls | Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; simple setting in accordance with the plot; represented in the medium of screen | Wenwu, no. 2 (2011): 40–46. |

| Shanxi | Xinjiang County Zhailicun tomb | 1311 CE | Unknown | Square, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Upper registers of eastern and western walls | Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; simple setting in accordance with the plot | Kaogu, no. 1 (1966): 33–35. |

| Shanxi | Jiaocheng County Peijiacun tomb | 1356 CE | Unknown | Octagonal, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Eastern and western walls | Monoscenic composition; decorated with hills, rivers, and clouds | Wenwu jikan, no. 4 (1996): 23–29. |

| Shanxi | Changzhi southern suburb tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Square, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Right side of eastern and western walls; northern wall | Monoscenic composition with painted frames; the rest unknown | Kaogu, no. 6 (1996): 91–92. |

| Shanxi | Yangquan Dongcun tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Octagonal, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Eastern and western walls | Large monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; decorated with landscape background; framed in black strips | Wenwu, no. 10 (2016): 32–43. |

| Shaan-xi | Yulin tomb (collected in isolation) | 1348 CE | Huang Zhong-qin and his wife | Unknown | Circuit in the upper register | Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; decorated with landscape background; framed in cloud-shaped space outlined by black lines | Wenbo, no. 6 (2011): 71–73. |

| Shaan-xi | Hengshan Luogetaicun tomb | Later period of Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Octagonal, single-chamber, masonry architecture | Circuit in the lower register of the dome | Multiple stories conflated into one composition; each story unit representing the typical episode; simple setting in accordance with the plot; without clear boundaries between story units | Kaogu yu Wenwu, no. 5 (2016): 63–74. |

| Shan-dong | Pingyin County Nanshantoucun tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Multi-chamber, masonry architecture | Four walls of the three chambers | Monoscenic composition representing the typical episode; most without background | Wenwu, no. 2 (2008): 41–55. |

| Shan-dong | Jinan Diesel Factory tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Square, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Upper register of northern, eastern, and western walls; circuit on the dome | Monoscenic composition in architectural settings; representing atypical episodes, e.g., in the case of Guo Ju, Wang Xiang, and Meng Zong | Wenwu, no. 2 (1992): 17–23. |

| Shan-dong | Jinan Licheng District Xingcun tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Round, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Between the coin-like tassel decorations on the dome | Monoscenic composition; painted perfunctorily; simple background | Wenwu, no. 11 (2005): 49–71. |

| Shan-dong | Jinan Licheng District Dongcun tomb | Yuan dynasty | Unknown | Round, single-chamber, wooden architecture in brick | Middle register of four walls | Monoscenic composition; decorated with simple landscape background; framed in space outlined by red and white lines | Wenwu, no. 11 (2005): 49–71. |

Author Bio:

Lucien is a PhD student in art history at the University of Chicago. He received his bachelor’s degree from Fudan University, Shanghai. During his BA, he spent an academic year at the University of Tokyo exploring Japanese collections of Chinese and East Asian art. A recent paper focused on images of filial piety stories at tombs in north China during the Yuan period. His current research interests lie broadly in Chinese burial art from the tenth to seventeenth centuries. He has also become interested in the exchange of visual and material culture on the Eurasian continent under Mongolian rule. He may be reached at lesun@uchicago.edu.