Charlotte Kinberger

The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Abstract

Artist Bruce Conner is perhaps best known as an early West Coast maker of assemblage. Of the innumerable assemblages Conner created between 1958 and 1964, nearly all of them contain nylon stockings as a central material. While Conner’s use of nylon in his assemblage works has been well documented—the material is so ubiquitous as to be impossible to ignore—the literature has failed to account for the history of nylon itself and the way this history informed Conner’s use of the material.

An early discovery of the petrochemical industry, which would come to dominate and define American consumer life, nylon was closely tied to World War II in both its early manufacturing and marketing. From its inception in the early 1930’s, nylon was viewed as an important competitor with the Japanese silk industry. This took on greater significance with the outbreak of the Second World War, during which all nylon production was diverted to war-related manufacturing. Nylon was and remained, however, a material for women’s stockings, and it was marketed in this way throughout the war despite widespread shortages of nylon hosiery. The shortages caused dramatic consumer dissatisfaction and constant media coverage. In other words, nylon was more than a material or a commodity—it was a sustained subject within the American imagination at midcentury.

Applying an interdisciplinary combination of textile history and art history, this paper uses the history of nylon’s discovery, manufacture, and marketing as a frame for understanding Bruce Conner’s consistent use of the material in his sculpture. The paper first establishes the close relationship between nylon and World War II, then suggests several instances in which Conner alludes to that history both verbally and in the work itself. The paper uses the history of nylon and its close connection to war-related manufacturing to expand on prior scholarship that has aligned Conner’s use of the material with sex and violence. Additionally, it offers a possible link between Conner’s assemblages and other works from his oeuvre that more explicitly engage the history and legacy of World War II and its connections to Cold War politics.

![]()

“It Is Very Difficult to Obtain Them by Legal Sources”: Bruce Conner’s Nylon Stockings

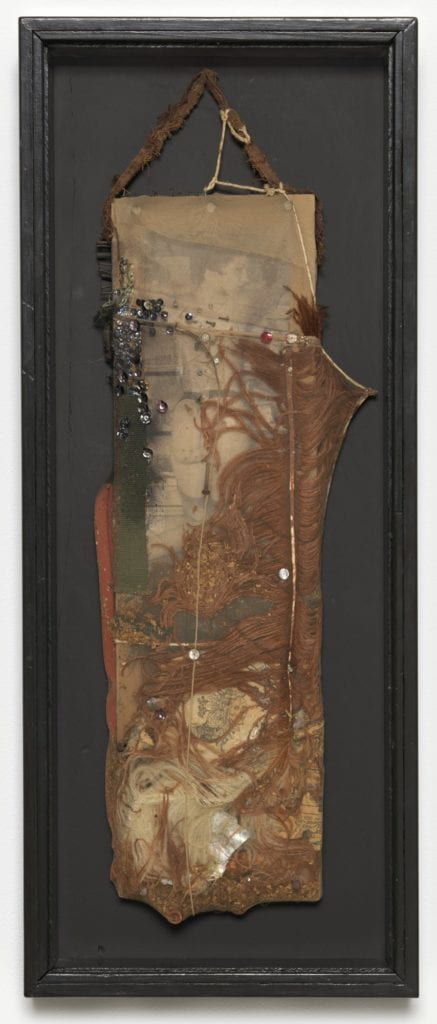

An oblong assemblage hangs from a strap of frayed burlap. It measures nearly two and a half feet long and over ten inches wide. Rusted nails puncture the periphery of the upper left-hand corner, leading the eye to a smattering of silver and purple sequins. Beneath this pierced and embellished exterior, several layers of nylon stockings obscure and reveal a black-and-white photograph of a woman. Her back faces us, her head turned to the right in profile. Her body is bare apart from a black garter belt and matching hosiery. Nails cut through her nylon shield, impaling and violating her body. Below and beside her image, feathers, fabric, shells, string, red rubber tubing, and loose tobacco threaten to break through the nylon encasement. A razor blade hovers menacingly in the mass. An image of a skull peaks through the feathers, a symbol of death. The work is Bruce Conner’s BLACK DAHLIA (Fig. 1). Named for one of the most infamous American murders to occur in the years immediately following World War II, the assemblage evinces Conner’s use of nylon as a veiling layer, a psychosexual motif, and an allusion to the ties between postwar commodities and militarized violence.

Just four year after making BLACK DAHLIA, Conner abandoned assemblage. A creative chameleon with an aversion to being pinned down, the artist left assemblage behind partially in response to his increasingly common definition by critics as the “nylon-stocking artist.”[i] Indeed, nylon stockings are a unifying material across almost all of the innumerable assemblages the artist made between 1958 and 1964. Yet, despite the specificity and ubiquity of the textile in Conner’s work from the period, few historians have dedicated more than a few paragraphs to his use of it. This is curious considering the fiber’s omnipresence, the entanglement of its invention and early marketing with the Second World War, and its continued media prominence in the postwar period. Nylon was more than a material. It was a phenomenon; one whose manufacture and media presence were deeply entrenched in the war effort. Given Conner’s well-documented antiwar stance, and his artistic engagement with World War II through other means and media, it is somewhat surprising that the literature has failed to examine the artist’s use of nylon in relation to its history. This paper will do precisely that, first sketching the history of the textile’s emergence and mass media coverage, and then addressing evidence for Conner’s awareness of this history and its appearance in particular assemblages.

Fig. 1 Bruce Conner, BLACK DAHLIA, 1960, photomechanical reproductions, feather, fabrics, rubber tubing, razor blade, nails, tobacco, sequins, string, shell, and paint encased in nylon stocking over wood, 26 3/4 x 10 3/4 x 2 ¾ in. (67.9 x 27.3 x 7 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Before we can account for Conner’s use of nylon, it is necessary to outline the material’s invention as both a fiber and a commodity. Nylon was discovered through a series of experiments conducted by the DuPont Company between 1928 and 1930.[ii] Almost immediately, as Susan Smulyan notes, DuPont directed the new material toward the manufacture of stockings, rather than “toothbrushes or synthetic wool or any number of other possibilities” the fiber presented.[iii] This decision had nationalist overtones: nylon offered an American alternative to Japanese-imported silk, and as a result, was positioned by the company and the press not only as silk’s new rival, “but as an anti-Japanese commodity.”[iv] Beginning with its first public appearance at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, nylon made headlines as a “Major Blow to Japan’s Silk Trade.”[v] This characterization gained even greater significance once World War II began.

In 1941, a year after nylons became available to the public, the United States placed an embargo on silk, seized all existing supplies from private manufacturers, and diverted them to wartime production.[vi] Six months later, all nylon was similarly redirected toward the manufacture of parachutes, munitions containers, and other military requirements.[vii] But first, to symbolize the United States’ economic independence from Japan, an American flag was woven in nylon and raised at the White House.[viii]

While nylon proved a boon to the United States war effort, its redirection resulted in widespread shortages of stockings throughout the country. In response, DuPont, along with help from the government and the press, promoted nylon’s strength, emphasized its importance to the war, and commended women’s contribution.[ix] This appeal to patriotic sacrifice caught on. As Susannah Handley chronicles, “Newspapers reported stories of girls ‘Sending Their Nylons off to War,’ carried photographs of leggy women taking their stockings off ‘for Uncle Sam,’ and described how it would take 4,000 pairs to make bomber tires.”[x] Amid this performance of patriotism, the demand for nylons persisted, and a black market emerged on which they were sold for as much as ten or twelve dollars per pair.[xi]

Even after the war’s end, DuPont repeatedly failed to satisfy the appetite for nylon stockings, resulting in widespread “nylon riots.”[xii] These so-called “riots,” in which women waited in line for many hours to buy a few pairs of stockings, made newspaper headlines for months beginning in September 1945.[xiii] The press coverage portrayed women as hysterical, violent, and unruly.[xiv] It also continued to linguistically link nylon to war with titles like, “Women Risk Life and Limb in Bitter Battle for Nylons,” and “Nylon Sale and No Casualties.”[xv] Thus, from its earliest inception through the postwar period, nylon and its market were intimately intertwined with the Second World War. And this connection was broadcast on a national scale. As Handley argues, “The scarcity of nylon stockings had turned them into symbols of luxury, and the passion with which they were pursued could almost be likened to the Beatlemania of the next generation.”[xvi] In other words, nylons were more than a commodity. They were a media-fueled sensation.

By the 1950s, nylon had come to symbolize “a new way of life, the future, the spirit of America and its mythical modernity.”[xvii] As the first fully synthetic fiber, nylon exemplified the new American normal, in which conspicuous consumption was made easier by cheaply manufactured chemical materials. It also served as a crucial precursor to many of the plastics that became ubiquitous in the fifties and sixties, which were critical to developments in Pop and Minimalism.[xviii] But unlike the Pop artists, who immortalized this unprecedented consumption with slick renderings of freshly-bought items—Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans come to mind—Conner used nylon to reveal the dark underbelly and broken promises of America’s new consumer culture.

Although Conner never explicitly referenced the above history, there are several instances where his comments indicate a coded consciousness of the craze for nylon and its association with war. One such instance occurs in the artist’s discussion of BLACK DAHLIA. Conner asserted that one of the themes of the work was, “the characteristics of femininity, which many times men turn into weapons…to attack the woman.”[xix] He continued, “Women wear all this armor that is incontrovertibly transformed into weapons against them.”[xx] This can be read as a general commentary on the sexism of American society, which simultaneously sexualizes women and then blames them for it. However, Conner’s language is a bit more specific. He is interested particularly in the garments and accessories women wear to perform their femininity, which he defines as “armor” that men convert “into weapons.” As apparel meant to confer modesty on the wearer, which is nonetheless eroticized, nylon stockings exemplify this conflict. Yet nylons were also literally transformed into weapons. As we have seen, DuPont originally developed nylon as a material for hose, but during World War II it was diverted to make tank tires, containers for explosives, and other wartime necessities. During the war, this diversion was used to advertise nylon’s strength with the promise that pantyhose would be available once the conflict concluded. When the war ended and manufacturers failed to meet the consumer demand this advertising had stoked, the consumer herself was chastised for her purportedly unreasonable expectations.[xxi] During these years of scarcity, women who went to buy nylons were caricatured in the media as crazed, frivolous fools.[xxii] Thus, a garment worn to protect women from accusations of immodesty was “transformed into [a] weapon against them.” Though this extrapolation may seem a stretch, that Conner would refer specifically to the worn characteristics of femininity in relation to BLACK DAHLIA is strange and significant. For in the violent crime to which the work’s title refers, Elizabeth Short’s body was discovered naked and mutilated, brutally stripped of its gendered attire.[xxiii]

Another instance in which Conner alludes to the militarized and gendered history of nylon comes from a 1963 student publication issued in conjunction with the University of Chicago art festival. In it, Conner published a joke plea, stating:

I am turning to nylon stocking assembling and would appreciate small dignified announcement in school paper that I have a nylon stocking fetish and place a dignified receptacle for contribution at the exhibit of my work. It is very difficult to obtain them by legal sources. … I will also hope (but not request openly) to get brassieres, panties, dirty photos, jewelry, feathers, psyloceben [sic], smoke writers in the sky, lamp posts.[xxiv]

This passage is crucial for several reasons. First, it indicates that Conner actively sought out the nylons he used, rather than finding them in secondhand shops or among the detritus of San Francisco’s Western Addition neighborhood, where he sourced most of the materials in his assemblages. This demonstrates that nylons held a singular importance for the artist that necessitated hunting them down rather than finding them organically. Conner’s solicitation for donations also mirrors the news reports that lauded women for donating their stockings to the war effort.

Second, on the surface Conner’s statement passes as a self-deprecating jab that apologizes for his use of hosiery, which during the early sixties would have been considered indecent. However, Conner is employing two definitions of “fetish” at once. In the first case, the term refers to an object of sexual fixation—usually a clothing item or body part—whose imagined or real presence is necessary for an individual to reach climax. Freud argued that fetishism compensates for the fear of castration, which arises when a little boy discovers that his mother lacks a penis. To assimilate this traumatic realization, the boy develops the fetish, which serves as a “substitute” for the mother’s missing phallus.[xxv] In the Freudian interpretation, then, the eroticism of the fetish is entangled with the threat of violence, an implication that maps onto the news reports suggesting that the demand for nylons amounted to a risk of “life and limb.” Beneath these sexual overtones, Conner’s statement also employs the understanding of the fetish as, “an object of irrational reverence or obsessive devotion,” to use the Merriam-Webster definition. In this way, Conner covertly references the consumerist furor that led to the so-called “nylon riots,” which turned stockings into an object of such profound desire that the frenzy at their sales frequently made headlines. This reading is confirmed by what Conner says next: “It is very difficult to obtain them by legal sources.” This refers to the black market for nylons that emerged during World War II. Yet, the temporal distance between the war and 1963, when Conner published this passage, allowed this sly reference to read instead as an insinuation that Conner had to resort to theft to satisfy his “fetish”. Conner therefore concealed his secondary meaning through sexual innuendo, which was reinforced by the materials he lists “but [does] not request openly.”

The polysemic, cryptic language Conner uses in each of these examples fits comfortably within the artist’s career-long resistance to easy definition, both in terms of his art and his artistic identity. As Laura Hoptman and others have identified, Conner engaged in “a lifelong struggle against being defined by technique, tendency, medium, or…reception.”[xxvi] Assemblage was only the first of several artistic media that the artist adopted and then abandoned; among the others were painting and photography. Conner was also deeply ambivalent about what he disparagingly referred to as “the art bizness,” which encompassed not only the art market, but also the institutional network of museums, image circulation, and press that kept the market afloat.[xxvii] A persistent prankster who was distrustful of language over vision, it follows that Conner would describe his assemblages in such oblique terms.[xxviii]

Just as he resisted easy categorization as an artist, he also encouraged complex and evolving understandings of his work. In 2005, Conner said of his assemblages, “I chose not to put the work into a box or a frame where it couldn’t be changed. I expected it to change. I never considered it to be ‘finished’. I put a date on it when I put it up on the wall, but that was all the date meant to me.”[xxix] This indicates that Conner hoped for physical interventions in his work and welcomed the possibility that the content might change as well. He was staunchly resistant to the idea that there exists one concrete truth, a point he made clear in an interview with Peter Boswell in 1986: “A rewarding experience for me is a narrative structure where you are not told what to think and what to do. Otherwise, that’s what you get in jail. That’s what you get with government. And when you get it in art, it can put you to sleep.”[xxx] It is clear, then, that he would not have entered anything into the public record that he felt was too specific or prescriptive. After all, one of the strengths of his assemblages is their visual complexity, which breeds multivalent meanings.

With that in mind, I do not intend to argue that Conner’s use of nylon is always in reference to the history outlined above. He used it in many ways across hundreds of artworks. Nonetheless, it offers a compelling and heretofore unexamined means for better understanding one aspect of his assemblages. Specifically, the history of nylon and its close connection to war-related manufacturing might bolster and expand prior scholarship that has more impressionistically aligned Conner’s use of the material with sex and violence. Additionally, it offers a link between Conner’s nylon-shrouded assemblages and other works he made throughout his life that more explicitly engage the history and legacy of World War II, and its connections to Cold War politics.

For instance, in 1959 and 1960, Conner made several works with military references in their titles, all of which contain stretched, wadded, or running nylon: RAT WAR UNIFORM, RAT SECRET WEAPON, MEDICAL CORPS FOR RAT WAR, RAT USO, RAT HAND GRENADE (all 1959), and GENERIC RAT HAND GRENADE (1960).[xxxi] The “rat” in all of these is a reference to Conner’s Rat Bastard Protective Association, a coalition of artists that he loosely assembled into a club sometime around 1957–58 (the exact date is unknown).[xxxii] The group’s name derived from the Scavenger’s Protective Association—San Francisco’s garbage collectors—with whom Conner felt an affinity due to their shared collection of detritus.[xxxiii] The artist once likened his use of nylon to the burlap bags that hung from the garbage collectors’ trucks as they hauled the trash away. [xxxiv] “Rat Bastard” came from an insult that Conner’s friend and fellow member Michael McClure heard while working at a local gym.[xxxv] In its appropriation of a slur, the name indicated a shared sense of alienation on the part of the members.[xxxvi]

John Bowles first suggested, and Anastasia Aukeman supports, the idea that these militant Rat Bastard-related titles indicated Conner’s desire to create “an army of Rat Bastards.”[xxxvii] This is an oddly straightforward reading, which neglects the fact that Conner was vehemently and vocally antimilitary. As Conner himself said, throughout the late fifties, he was anxiously aware that he was draft age.[xxxviii] He viewed the draft as “the worst violation [he] could imagine,” and moved to San Francisco from his hometown of Wichita, Kansas, in part because he felt it offered better odds of gaining military exemption.[xxxix] Thus, to assume that Conner’s use of war-related language in his titles indicated that the artist was harboring a hope of martial insurrection seems off the mark. Instead, it seems possible that through these titles, Conner was referring to the nylon in these early assemblages. In particular, RAT WAR UNIFORM might be understood as linguistically combining nylon’s status as garment and wartime aid, while RAT SECRET WEAPON could refer to the profound importance nylon played in military manufacturing.

This reading is reinforced when understood in relation to other assemblages Conner made the same year. Rachel Federman suggests that beginning in 1959, Conner made several works incorporating black wax that expressed “his profound disillusionment with U.S. foreign and domestic policy during the Cold War, and with the nuclear arms race in particular.”[xl] Numerous nylon works from the same year suggest a similar, though veiled critique.

Specifically, Conner created a suite of spider-themed works that are worth exploring in more depth: SPIDER LADY, SPIDER LADY NEST, SPIDER LADY HOUSE, SPIDER LADY DUNGEON, and ARACHNE (all 1959). Aukeman proposes that these works explore “hidden or repressed sexual fantasies.”[xli] However, given their distinctly abstract rendering and lack of sexual imagery in comparison with Conner’s other assemblages, there is room for a more nuanced assessment.

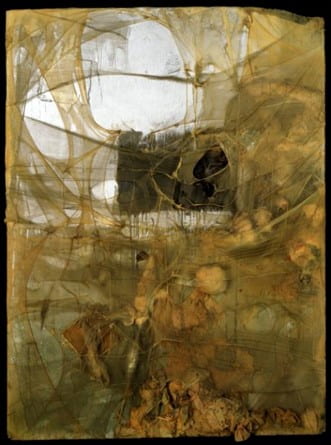

ARACHNE (Fig. 2), for instance, is a large-scale assemblage measuring approximately five feet high by four feet wide, with a depth of four inches. The work is shrouded in nylon cobwebs, the stockings pulled taut to the point of breaking, creating stiff arabesques that run over the surface of the work. Beneath this top screen of ripping and running nylon, still more nylon is wadded up, knotted, and balled. The accumulation of sheer layers simultaneously holds the work together and hides it from view, concealing a doll’s head, beads, and bits of newsprint trapped like insects beneath. The effect is one of bodily, bandaged accumulation, intestinal tubes and nodules of nylon suspended on the work’s painted collage support. In the top center of the composition, a cavernous abyss is rendered in dripping black paint, obscured by overlapping lines of nylon and wire.

Fig. 2 Bruce Conner, ARACHNE, 1959, mixed media: nylon stockings, collage, cardboard, 65 3/4 x 48 3/4 x 4 1/4 in. (167.0 x 123.8 x 10.7 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

As Aukeman points out, the title of the work refers to the Greek myth of Arachne, a mortal weaver of such tremendous skill that she enraged the goddess Athena, who retaliated by ripping Arachne’s tapestry from her loom and turning her into a spider.[xlii] Aukeman ponders whether Conner identified with Arachne or Athena,[xliii] but I would suggest that the artist invoked the myth as myth, rather than psychologically aligning himself with one of its protagonists. The spider woman offers ambiguous symbolism as a skilled weaver, a maternal protectress, and an entrapping temptress. As we have seen, seduction and the threat of corporal harm are interwoven within fetishism, and Conner was quick to acknowledge the fetishistic quality of nylon stockings. This characteristic is visually expressed through bulbous nylon appendages that cover the surface of ARACHNE, conjuring Freud’s assertion that the fetish is a substitute for the mother’s missing phallus. The artist visualizes the menace of castration and death Arachne poses as both mother and seductress through splatters of red pigment that lend the masses of nylon a bloody bandage-like effect. But Arachne is also a woman imprisoned within a spider’s body, making her both the trapper and the trapped. In this way, she exemplifies Conner’s assertion that feminine accessories like nylon stockings captured women within a contradictory expectation of allure and modesty, an objectifying force that fed postwar consumerism and gendered violence alike.

Kevin Hatch argues that ARACHNE annihilates the subjecthood of the viewer: “its nylon strands veil nothing but its own voided core,” offering “no place for the observer whatsoever, no escape, no refuge.”[xliv] As a dangerous, seductive woman, we might say that Arachne is the agent of this obliteration, luring innocents to her web. Yet this threat of destruction and death has another layer of meaning within the context of the myth. The tale of Arachne is a cautionary one, a warning that humans should not claim the power of gods, lest they be punished for their hubris. In Conner’s formulation, the stretched, wrapped, and ripped nylon in the work is Arachne’s web, which was once a beautiful tapestry, but due to the arrogance of its weaver has become abject and ruined, breeding only darkness and decimation. In this respect, the work might be understood in relation to Conner’s lifelong fascination and abhorrence toward the nuclear bomb and the arms race of the Cold War, which represented such an unprecedented and devastating assertion of dominion over nature and human life as to be almost biblical in proportion. As a child, Conner watched documentation of the July 25, 1946, submarine bomb test conducted at Bikini Atoll.[xlv] The footage left a profound impression on the artist and remained an object of fascination and fear that Conner repeatedly used in his work. Most notably, it appears in his 1976 film CROSSROADS, “which consists entirely of declassified government footage of the underwater Bikini test explosion.”[xlvi]

Beyond its marketing and manufacturing associations with World War II, nylon has an eerie connection to the development of the atomic bomb. DuPont, the same petrochemical company that invented the textile, was a major player in the Manhattan Project, developing the plutonium that was a key ingredient in the bomb dropped on Nagasaki.[xlvii] Whether Conner was aware of this connection is hard to know. If he was, he never stated it outright in the myriad interviews he gave throughout his career. Nevertheless, it confirms a thematic thread that ran through the heart of so much of his oeuvre: the simultaneous seduction and repulsion he felt in response to atomic warfare.

At the very least, Conner’s use of nylon might be interpreted as a nod to the fragility of life during the Cold War era, when the possibility of an impending nuclear attack never felt far away. Describing the first time he took the hallucinogenic drug peyote, Conner said,

I experienced myself as this very tenuously held-together construction—the tendons and muscles and organs loosely hanging around inside—and it seemed like at any moment disaster could strike and you could fall apart…. you were just held together by this thin skin and strings of flesh. And shortly after that I started working on a number of named pieces, but the first one was Snore, which has all these organ-like lumps of things.[xlviii]

SNORE (Fig. 3) is composed almost entirely of nylon; its delicate fibers bunched into pendulous blobs that are held inside stretched layers of stringy nylon skin. In this way, SNORE isolates another crucial aspect the Conner’s use of nylon that so many scholars have hedged toward but never stated. In its closeness to the body, its fleshy tones, and its elasticity, nylon acts as a kind of second skin, albeit one that is far from universal in its limited range of pale hues. Nonetheless, Conner exploited this quality in many of his assemblages, lending them a corporal presence. Conner often emphasized the gendered nature of this surrogate skin by incorporating costume jewelry and other feminine “masks,” as he called them.[xlix] But without these, the effect is simply bodily, allowing Conner to create works like SNORE. The assemblage’s title is at once comic and foreboding, for the body is most vulnerable in sleep. Towards the top of the work, a metal can with a black mouth gapes at the viewer. Conner’s title implies slumber, but the abstracted figure could just as easily be screaming.

Fig. 3 Bruce Conner, SNORE, 1960, wood, nylon, and metal, 36 1/2 x 17 1/2 x 21 1/2 in. (92.7 x 44.5 x 54.6 cm), Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

The corporeality Conner could conjure with nylon was apparent to him from the very first work he defined as an assemblage, RATBASTARD (Fig. 4). The artist described the piece as a “wounded” painting covered with nylon stockings, affixed with “a picture of a cadaver on an operating table…with wire and wood representing bones and structure.”[l] For Conner, the work took on its own “persona.”[li] In this description, the wounded painting and the injured body become one and the same, as the work’s various bodily features—nylon skin, wood bones—combine to create a figure. However, the specter of American violence and militarism was always present too, as evinced in RATBASTARD’s slashed canvas and corpse, as well as nails and bloody brown paint stains that appear around the periphery of the work (Fig. 5).

Figs. 4 & 5 Bruce Conner, RATBASTARD, (recto and verso), 1958, wood, canvas, nylon, newspaper, photographic reproduction, wire, oil paint, nails, bead chain, etc., 16-1/2 x 9-1/4 x 2-3/4 inches, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN.

The alignment of nylon with United States military manufacturing, and the visual parallel Conner drew between the material and violence provide a potential answer to a question that has not yet been posed in the literature. Namely, why Conner almost entirely stopped using nylon when he moved to Mexico City with his wife Jean in 1961. Of the many assemblages Conner made while the couple was living there between 1961 and 1962, only a few incorporate the material at all. Of course, this was partially due to the difference in available tools, and the couple’s lack of a social network in Mexico. Conner found that the people of Mexico did not discard their belongings as readily as Americans, making the refuse he was accustomed to using scarcer.[lii] Additionally, their short-term stay likely prevented the artist from sourcing nylons from friends or acquaintances.

Nonetheless, there was also a thematic reason for Conner’s shift in materials. In a letter to Museum of Modern Art curator William Seitz, Conner wrote of his time in Mexico, “It is difficult for me to understand USA violence here…I feel I have left most all the oppressive scene behind me.”[liii] Given the myriad connections between “USA violence” and Conner’s use of nylon outlined above, this statement is a compelling argument for the artist’s sudden stop in its use. This reading is bolstered by the fact that shortly after the artist returned to the United States in 1963, he submitted his coded request for nylon donations at the University of Chicago.

One year later, in 1964, Conner ceased making assemblages altogether. This was partially due to the increasing institutionalization and popularity the form had gained in the preceding years. William Seitz, the same curator Conner wrote to from Mexico, had organized the landmark exhibition The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961. The show gave a name, historical lineage, and establishment approval to a style that only a few years earlier had seemed marginal. For Conner, the increasing attention being paid to assemblage and the resultant notice his own work was generating threatened stale convention. As Peter Boswell discerned, Conner “resented the pressure to continue in the same mold. But…he [was also] tired of the static nature of what had become, in just a few years, ‘conventional assemblage making.’”[liv] Aukeman notes that one of the reasons Conner was initially attracted to assemblage was that it lacked a name or style, and as such, was free from tradition or established norms.[lv] Once recognition and labeling took hold, Conner jettisoned the form that had brought him fame for fear of being pigeonholed.

But Conner also grew tired of the object-ness of his assemblages. He began to see in them, “an unnecessary gross attachment to property and objects,” in which he was “entrapped” due to his need to preserve and store them.[lvi] Work that was once outside and critical of the capitalist system due to its discarded materiality began to feel corrupted by commerce. “I see a continuing campaign,” Conner said, “on the part of controllers of art to turn these things into commodities, to define what individuals are doing with their hands so that they conform to a political, social, and economic agenda that pertains to the establishment, finance, and the art world.”[lvii] Conner refused to participate in that process, and so, famously, he “stopped gluing big chunks of the world in place.”[lviii]

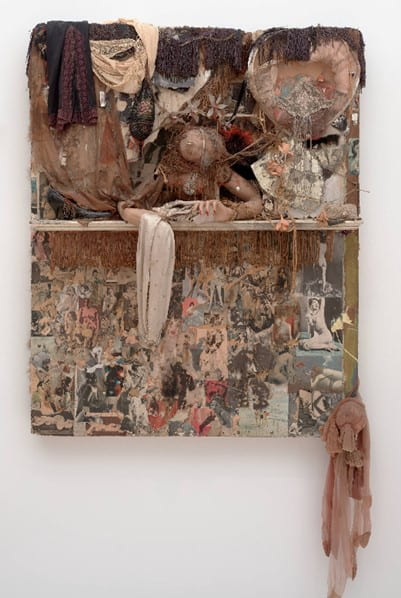

Conner’s final assemblage, LOOKING GLASS (Fig. 6), can be understood as a virulent critique of American consumer culture, the commodification of femininity, and in turn, the commodification of women themselves. A confrontational final opus measuring five by four feet, the work reaches out toward the viewer with mannequin arms, conjuring a fortuneteller figure. Her head is not a woman’s but a blowfish, its spikes poking through layers of suffocating nylon, its lips gasping for breath. She emerges from layers of feminine accouterment: nylons, lingerie, fringe, feathers, fake flowers, costume jewelry, a high-heeled shoe, and a beaded purse. Conner once called accessories of this sort “demonic devices” that do not represent women, but instead constitute objects of martyrdom akin to “the chains and the locks and the crowns of thorns.”[lix] And indeed, the figure in LOOKING GLASS is bound to them with rope that wraps around her wrist and cuts across her throat.

Fig. 6 Bruce Conner, LOOKING GLASS, 1964, mixed media on Masonite, 60 1/2 x 48 x 14 1/2 in. (153.67 x 121.92 x 36.83 cm), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA.

Below the ledge on which she rests, the bottom half of the work is covered in ripped and stapled pornography. Hundreds of nude women populate this portion of the piece, revealing an subterranean world where objects of desire are no longer the commodities above, but women themselves. In the lower right corner, a cascading conglomeration of nylons connects the two spheres of the work, making clear that they are one and the same. As an object of both sexual and consumer fetishism, nylon stockings eliminate the difference between them, revealing American consumption as the burden borne and worn by women. In keeping with Conner’s earlier work, there is an inherent violence to this wearing and bearing, exemplified by the layers of nylon that seem to strangle and blind the blowfish face above. In this way, nylon becomes a metonym for the entanglement of consumerism with gendered subjugation and state brutality. Shards of broken mirror and the work’s title make clear that this is not Conner’s personal psychosexual fantasy, but a reflection of us all. LOOKING GLASS is the barbarism of American consumerism and sexism staring you in the face. For though the blowfish is blinded, just above it, a woman’s eyes peer out beneath layers of fringe and flowers.

Knowledge of nylon’s early history is crucial to the analysis above. Without it, LOOKING GLASS reads as an overblown fetish itself, its accumulation of sexual imagery and objects serving merely to reinforce their venereal charge. With it, the work becomes a broader meditation on the ills of American production and consumption, whether of objects, images, or ideology. Nylon, through its manufacture and marketing, was key to the production of all three. As such, it was a complex material that Conner mined in myriad ways.

Its erotic and gendered associations could be mobilized to great effect, but this was far from the only meaning Conner unraveled from the fiber. Its interwoven history with World War II in its production and publicity, as well as its resultant status as an overvalued luxury good, proved equally fruitful for the artist. Resolutely antiwar, Conner used nylon to create concealed allegories relating to the ruin of human invention by military conflict, and the fragility of human life in the age of nuclear weapons. Nylon’s corporal qualities allowed Conner to create pseudo figures with the fiber, conjuring polyp-like protrusions, entrails, and skin-like encasings. He also never lost sight of the material’s status as both a sexual and consumer fetish.

Nylon was perhaps the quintessential American commodity at midcentury. It represented the country’s nationalist economic agenda, served as a crucial weapon during the Second World War, and was critical to the chemical engineering developments that engendered rampant postwar consumerism. In all of these ways, it provided the perfect material means for Conner to question American consumption, Cold War politics, patriarchal gender constructions, and violence writ large. However, nylon’s greatest potential lay in its flimsy and flexible materiality, for unlike a Campbell’s soup can or a Brillo box, which cannot escape their concrete commodity status, nylon stockings are more surface than object. As such, they allowed Conner to achieve the kind of narrative multiplicity and ambiguity for which he strove in all his artwork.

Endnote

[i] Peter Boswell, “Bruce Conner: The Theater of Light and Shadow,” in 2000 BC: the Bruce Conner story Part II, ed. Peter Boswell, Bruce Jenkins, and Joan Rothfuss (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1999), 44.

[ii] Susan Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon: The Struggle Over Gender and Consumption,” in Popular Ideologies, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 41.

[iii] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 47–8.

[iv] Smulyan, 44; Susannah Handley, “‘N’ Day: The Dawn of Nylon,” in Nylon: The Story of a Fashion Revolution: a celebration of design from art silk to nylon and thinking fibres, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 35.

[v] “$10,000,000 Plant to Make Synthetic Yarn: Major Blow to Japan’s Silk Trade Seen,” New York Times, Oct. 21, 1938.

[vi] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 55.

[vii] Smulyan, 55.

[viii] Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 48.

[ix] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 56.

[x] Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 48.

[xi] Handley, 48.

[xii] Handley, 50; Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 58.

[xiii] Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 50.

[xiv] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 61–2.

[xv] Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 50.

[xvi] Handley, 50.

[xvii] Pap Ndiaye, Nylon and Bombs: DuPont and the March of Modern America, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 2.

[xviii] Ndiaye, Nylon and Bombs, 2; Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 40.

[xix] Bruce Conner and John Yau, “Folded Mirror: Excerpts of an Interview with Bruce Conner,” On Paper 2, no. 5 (May–June 1998), 34.

[xx] Conner and Yau, “Folded Mirror,” 34.

[xxi] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 61–62.

[xxii] Smulyan, 70.

[xxiii] Greil Marcus, “Bruce Conner’s Black Dahlia,” in Bruce Conner: It’s All True, ed. Rudolf Frieling and Gary Garrels (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 79.

[xxiv] Bruce Conner quoted in Rebecca Solnit, Secret Exhibition: Six California Artists of the Cold War Period, (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1990), 63.

[xxv] Sigmund Freud, “Fetishism,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 21, trans. and ed. James Strachey, et al, (London: Hogarth Press, 1961), 152–157.

[xxvi] Laura Hoptman, “Beyond Compare: Bruce Conner’s Assemblage Moment, 1958-64,” in It’s All True, ed. Rudolf Frieling and Gary Garrels (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 283.

[xxvii] Hoptman, “Beyond Compare,” 282.

[xxviii] Greil Marcus, “Bruce Conner: The Gnostic Strain,” Artforum 31, no. 4 (Dec. 1992), 75.

[xxix] Hans Ulrich Obrist and Gunnar B. Kvaran, “Interview: Bruce Conner.” Domus, no. 885 (Oct. 2005), 23.

[xxx] Bruce Conner in discussion with Peter Boswell, February 11, 1986, quoted in Boswell, “Bruce Conner: The Theater,” 31.

[xxxi] Anastasia Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland: Bruce Conner and the Rat Bastard Protective Association, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016), 138. I cite this list because it seems that these works are no longer extant except in their printed descriptions.

[xxxii] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 138.

[xxxiii] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 71; Kevin Hatch, “‘It has to do with the theater’: Bruce Conner’s Ratbastards,” October 127, (Winter 2009), 117.

[xxxiv] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 138.

[xxxv] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 61.

[xxxvi] Hatch, “It has to do,” 117.

[xxxvii] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 138.

[xxxviii] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 64.

[xxxix] Bruce Conner quoted in Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 64; Rachel Federman, “Bruce Conner: fifty years in show business,” in Bruce Conner: It’s All True, ed. Rudolf Frieling and Gary Garrels (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 29.

[xl] Federman, “Bruce Conner,” 83.

[xli] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 138.

[xlii] Aukeman, 142.

[xliii] Aukeman, 142.

[xliv] Hatch, “It has to do,” 132.

[xlv] Federman, “Bruce Conner,” 83.

[xlvi] Federman, 83.

[xlvii] Ndiaye, Nylon and Bombs, 2 and 143.

[xlviii] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 62–3.

[xlix] Solnit, 65.

[l] Marc Selwyn, “Marilyn and the spaghetti theory,” Flash Art 24, no. 154 (Jan.–Feb. 1991), 94.

[li] Selwyn, “Marilyn and the spaghetti theory,” 94.

[lii] Federman, “Bruce Conner,” 86.

[liii] Letter from Bruce Conner to William Seitz, undated (probably Dec 1961) BCP quoted in Federman, “Bruce Conner,” 86.

[liv] Boswell, “Bruce Conner: The Theater,” 44.

[lv] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 188.

[lvi] Selwyn, “Marilyn and the spaghetti theory,” 94.

[lvii] Selwyn, 97.

[lviii] Obrist and Kvaran, “Interview: Bruce Conner,” 23.

[lix] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 65.

Author Bio:

Charlotte Kinberger is a master’s candidate at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, focusing on modern and contemporary art. Her research interests include revisionist histories of Modernism, “Craft” and “Folk” art, textile and costume history, and feminist and critical race theory. She studied Art History and Material Culture at Sarah Lawrence College and the University of Oxford and has held internship positions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. More recently, she has served as the Gallery Manager at James Fuentes, New York, and the Assistant Director at Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco.