![]()

MA Student, The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

![]()

In his own words, Ed Ruscha’s primary artistic interest is the “attention and time given to a subject that doesn’t need attention and time.”[1] As the building blocks of culture, the endless permutations of the Latin alphabet bank called ‘words’ comprise every code–social, ontological, moral, legal, or otherwise–by which linguistic beings abide. The word operates in relation to others, yet languishes on its own, unmoored from meaning and vulnerable to myriad interpretations. This “little warrior,”[2] then, is ripe for Ruscha’s timely, if ambivalent, rescue, plucked from the verbal cacophony of letters and “elevat[ed]…to a see-able status.”[3]

The literature on Ruscha’s romance with language amounts to several volumes; the textual evidence for the affair spans his vast oeuvre. In squaring Ruscha with Pop, however, his deployment of words as found subjects with nuanced histories remains under-interrogated. Lisa Turvey (née Pasquariello) devotes significant energy to the words Ruscha selects in a 2005 essay where she argues for the artist’s interest in the “substance of his subjects,”[4] summing material and word so that each becomes greater than its parts. Ruscha’s words are deliberate weapons, sharpened by their pictorial, rather than verbal, contexts. From whence does this arsenal derive? Ruscha keeps a diary, in which he scrawls overheard exchanges that excite him. A few examples:

“It’s your baby. You rock it.”[5]

“What are you doing, training for a race?” “No, racing for a train.”[6]

Yve-Alain Bois confirms, “[Ruscha’s words] are scoriae that catch his eye on billboards or his ear on the radio while he is driving,” and continues with an allusion to a favorite aphorism of Ruscha: “they are the waste that he retrieves.”[7] This dedicated listening is the artist’s unique talent. Through such tuning in, Ruscha captures the complex connotations of American culture’s linguistic cast-offs, especially those abuzz during the capitalist-crazed Pop years, to transmute vernacular expression into conceptually rich investigations of the arbitrary link between sign and signified, image and word. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in Falling But Frozen (1962; fig. 1), one of three Ruschas shown in California curator Walter Hopps’s landmark exhibition focused on West Coast Pop the same year.

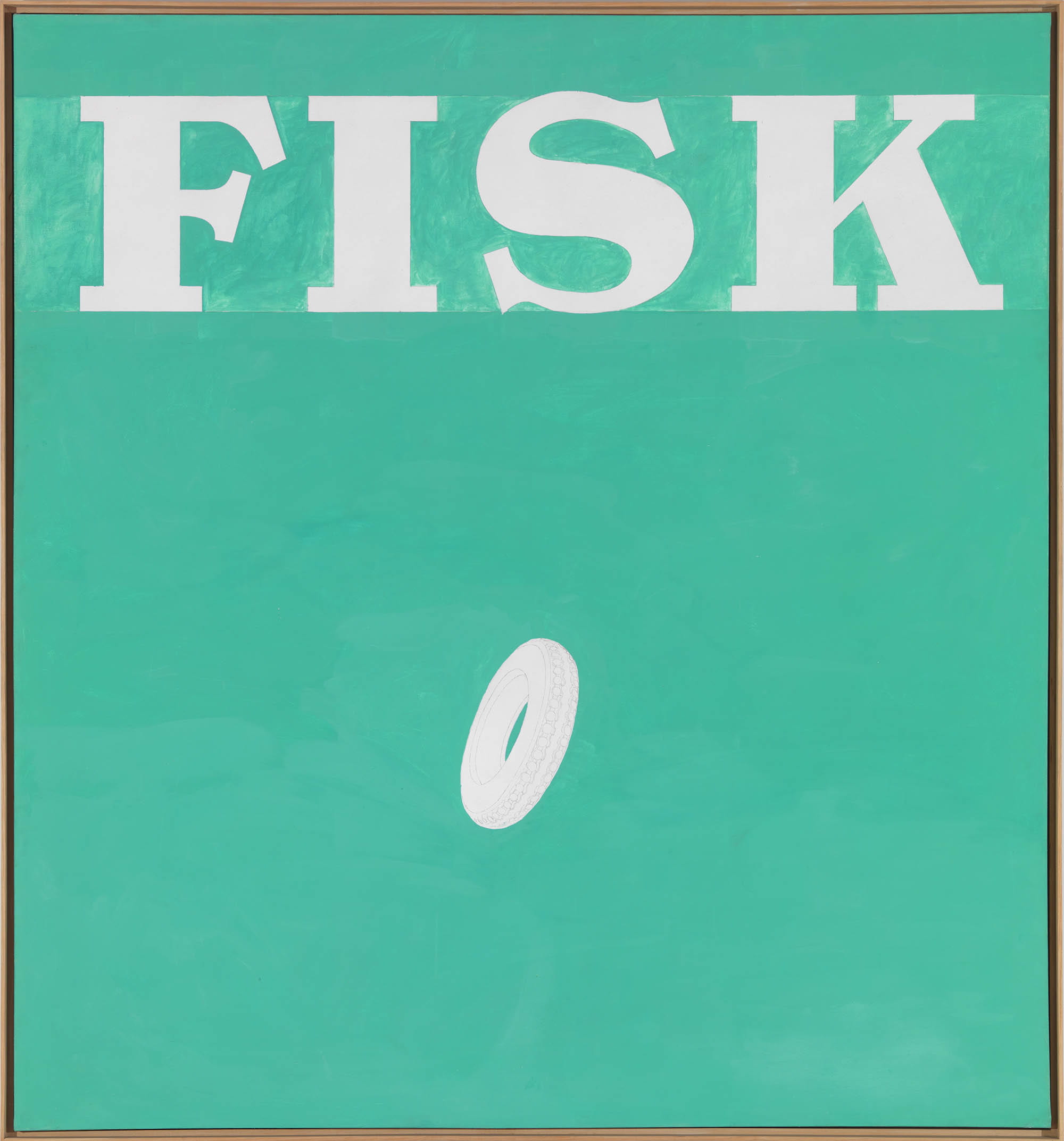

Fig. 1. Ed Ruscha, Falling But Frozen, oil and pencil on canvas, 71 1/8 x 67 1/4 in. (180.7 x 170.8 cm.), 1962. Photo: Robert McKeever, Gagosian Gallery.

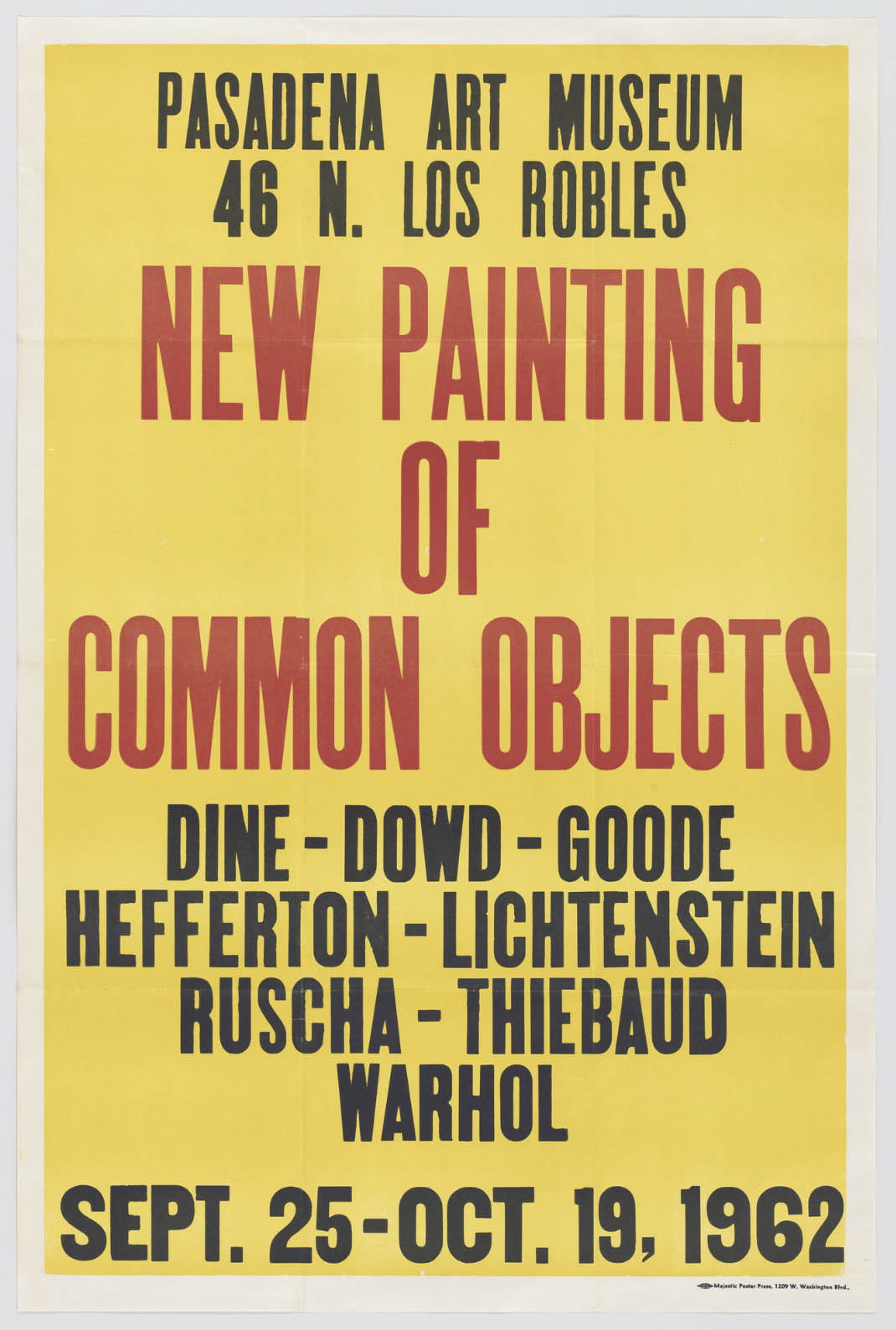

Hopps’s New Painting of Common Objects at the Pasadena Art Museum proved a fulcrum event for the crystallization of American Pop, setting in dialogue for the first time the work of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jim Dine with that of Ruscha, Wayne Thiebaud, Joe Goode, and others. The former trio represents a small sample of the New York vanguard that was, in those early days, turning away from traditional art materials, like oil and graphite, toward the more quotidian trappings of the supermarket aisle to both celebrate and critique the newly rampant American consumerism facilitated by a post-World War II economic boom. Though avant-garde sensibilities on the East Coast had been trending away from the emotion-ridden Abstract Expressionism of the fifties for a few years, following a similar movement in Europe, gallerist Sidney Janis did not mount his category-defining International Exhibition of the New Realists until the end of 1962, and then with minimal West Coast representation. Thus, Hopps’s prescient pairings of artists, all in the nascent years of their careers, were the first, if only by a few months, to affirm Pop’s burgeoning efficacy. Artists across the country came to the same conclusions at the same moment, yet in various visual manifestations and relative isolation from one another to underscore a pressurized American zeitgeist exploding onto canvas. Tellingly, Hopps tapped twenty-four-year-old Ruscha, an Oklahoma City transplant and recent graduate of Los Angeles’s progressive Chouinard Art Institute, to design the exhibition poster–a striking yellow backdrop for bold black text over and underneath the crimson title (fig. 2). In a spontaneous act of artistic distancing encouraged by Hopps, Ruscha recalls “dictating the text over the telephone to a commercial printer, with the instruction ‘Make it loud!’”[8] From the beginning, then, Ruscha sought to cause an audible splash in the picture pool in his pursuit of “visual noise.”[9] While his Pasadena show conspirators homed in on the seen vestiges of post-war commerce–stamps for Warhol, hairspray for Lichtenstein, milk bottles for Goode–Ruscha took as his ‘common object’ the spoken brand name, with the referenced product added as a downsized iconic complement to stoke semiotic tension.

Fig. 2. Ed Ruscha, New Painting of Common Objects, letterpress on paper, 40 x 26 1/8 in. (101.6 x 66.3 cm.), unknown edition, 1962. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

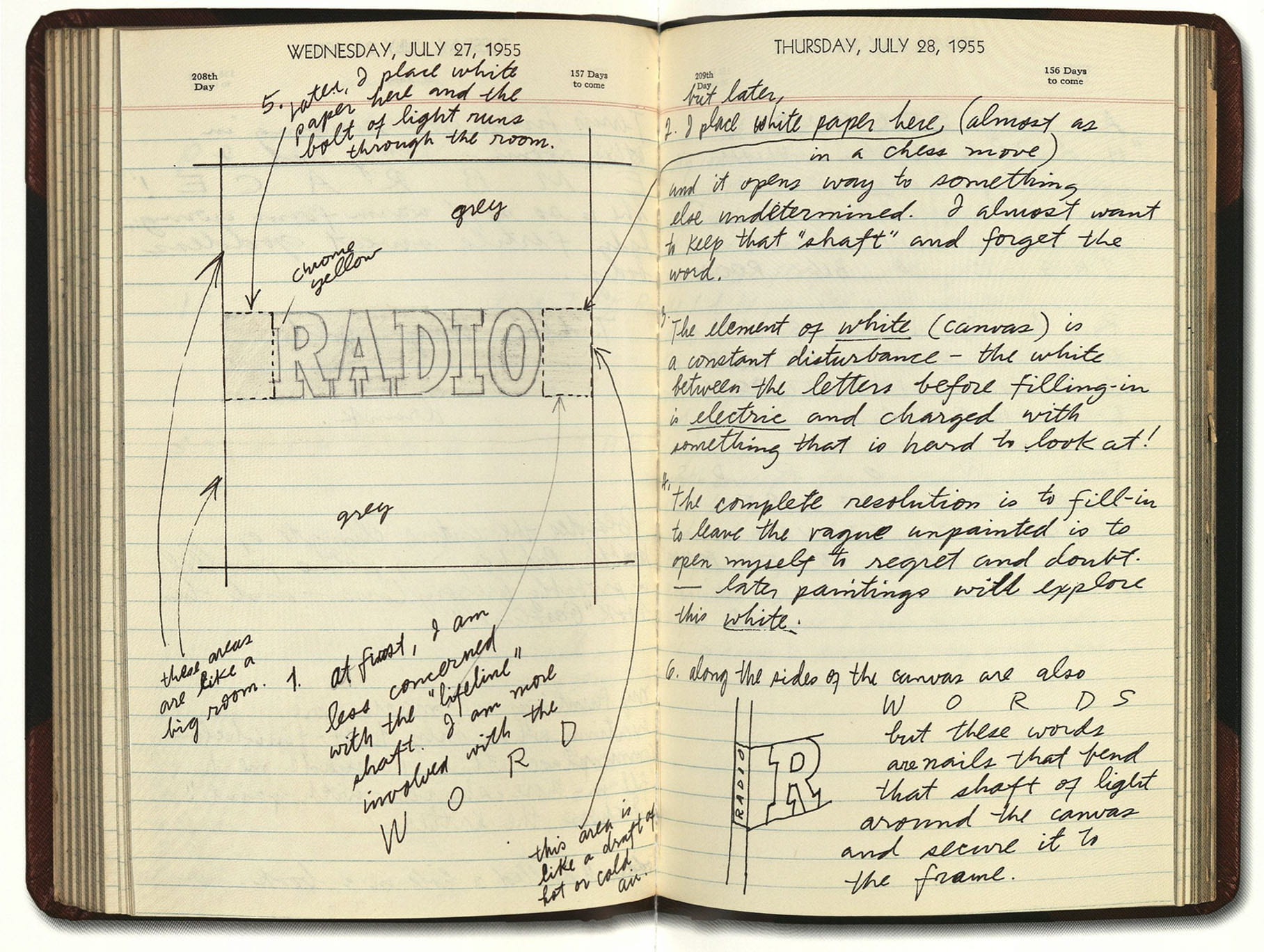

In Falling But Frozen (1962), stencil-like graphite lines delineate a brushy rectangle that confines the letters ‘F’, ‘I’, ‘S’, and ‘K’ to the upper register. Sanctified in compositional space, the letters recall the advertising layout process, which depends on the page edges to guide spacing. Notwithstanding Ruscha’s formulaic 67-inch-wide canvas,[10] the alphabetical elements are exempt from obedience to proportion, since letters are inherently without predetermined scale: they “exist in…this anonymous world of no-size.”[11] Thus, Ruscha defines his own textbox, according to the physical limitations of his chosen support. In preliminary notes for another 1962 painting with the same feature, Ruscha writes, “this area is like a draft of hot or cold air,” and then refers to the remaining canvas partitions above and below the textbox as “a big room” (fig. 3).[12] If the graphic area is the unwanted breeze invading the domestic image space through a shattered windowpane, then Ruscha’s language paintings are themselves shiver inducers within the history of pictures, cutting through convention to confuse semantics with aesthetics.

Fig. 3. Ed Ruscha, studio notebook entry, 1962. Illustrated in Edward Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, Volume One: 1958-1970, ed. Pat Poncy (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2003), 58-59.

Taken together, the capital letters read ‘FISK’ and mimic the distinct typography of the American tire company that prospered during the early twentieth century, before the Great Depression forced a restructuring and sale in 1940.[13] The acquiring corporation retained the brand name, partly due to the effective advertising imagery Fisk employed throughout its independent existence (figs. 4-5).[14] At its savviest, Fisk featured a yawning, pajama-clad child, a dripping candle in one hand and a massive tire slung over the shoulder in lieu of a blanket, with the unforgettable slogan: “Time to Re-Tire? (Buy Fisk).” The conflation of ‘tire’ as automobile part and ‘tire’ as nearing exhaustion cast Fisk not only in a mechanical role, but also in a therapeutic one–consumers trusted Fisk to both protect their families’ commutes and provide respite from burning the midnight oil by burning rubber instead. This found wordplay likely appealed to Ruscha for its cleverness, enhanced by the accompanying imagery.

Fig. 4. Fisk Rubber Co. advertisement, Theatre Magazine, July 1923, p. 63.

Fig. 5. Fisk Rubber Co. advertisement, Country Life in America, October 15, 1912, p. 83.

More ad-akin than Ruscha’s lone words, Falling But Frozen includes the object of its word’s affection, which, contrary to the letters crowning it, possesses indisputable dimension. Whereas elsewhere Ruscha commits to faithful reproduction of objects in “actual size,” here he sketches the tire roughly three times smaller than what would suit a standard vehicle.[15] Ironically, the vernacular elements, typically free from defined size, strictly adhere to Ruscha’s arbitrary scale, while the banal element that relies on a specific size for its purpose shrivels to an equally arbitrary inconsequence. In such diminution, Ruscha’s tire wobbles between function and failure, while its angular perspective implies multi-directional motion. In falling sideways to the unseen ground, the wheel escapes its duty to go seamlessly round and round; in falling vertically to the lower edge of the canvas, it references the infinite virtual space beyond the picture plane. The meticulous tread is rendered both useless, as Fisk’s one-time runaway success tumbles off-course, and diagrammatic, as a mere “exposition of relations of forces” bereft of force itself.[16] Enacting the artist’s penchant for verbiage, a gentle mental pivot recasts the tire icon as the letter ‘O,’ whose smaller size relative to the other letters insinuates depth–‘O’ falls into the turquoise void behind the picture plane, parroting the shape of a screaming human mouth, frozen in fear.

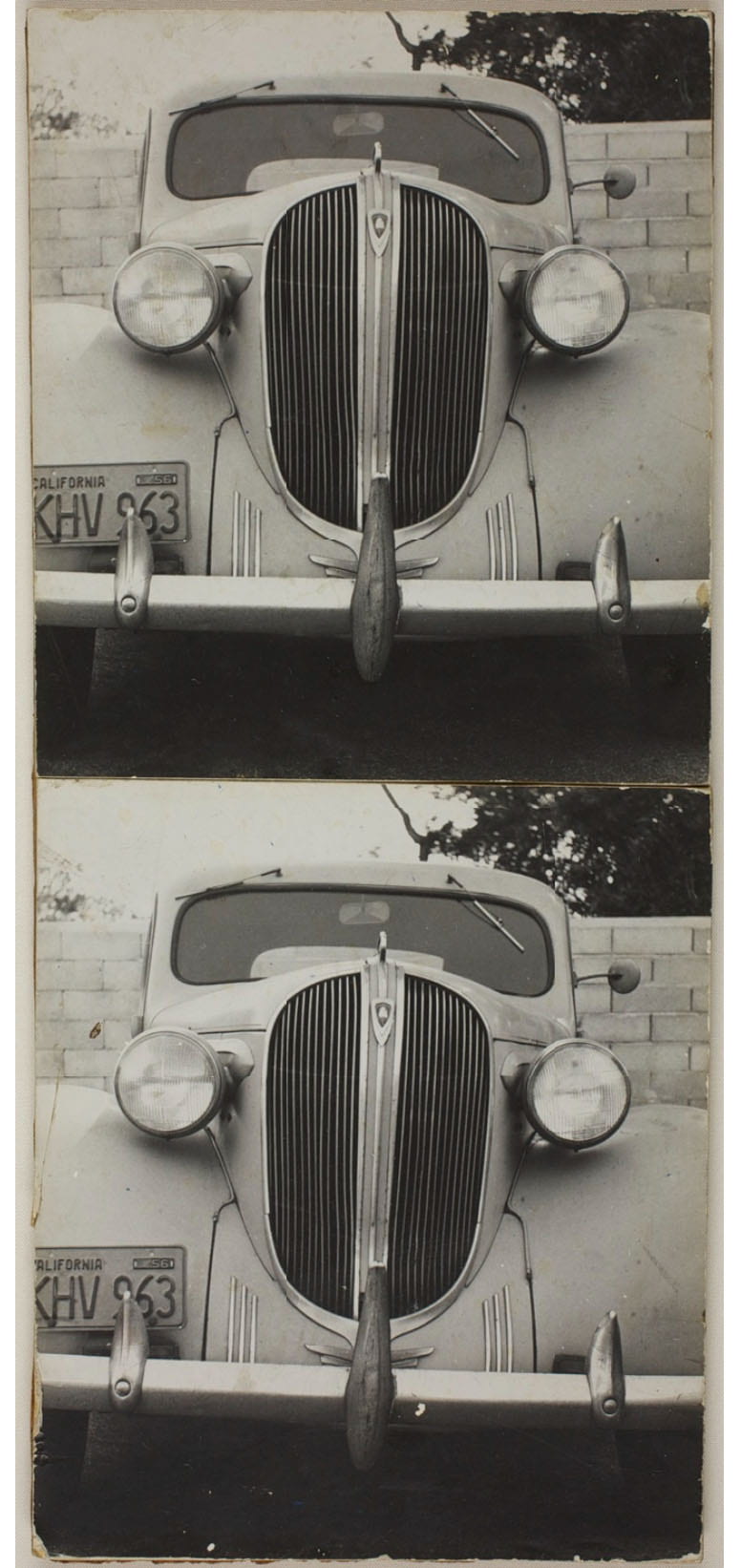

These aesthetic choices assume renewed ambiguity insofar as Fisk’s product facilitated a crucial facet of Ruscha’s Los Angeles circuit: the car. A broader discussion of West Coast car culture aside, Ruscha’s personal engagement with the automobile, evidenced by his road trip from Oklahoma, horizontal documentaries of California boulevards, and early photography, suggests his awareness of the relevance of Fisk’s industry (fig. 6). Ruscha understood his own car as “a rite of passage…a vehicle to take me places I would dream about.”[17] Bordering on mystical terms, Ruscha’s description sublimates the personal transportation device into divine apparatus; the driver’s seat becomes the portal to a fantasy world. The wheel undergirds the whole endeavor by operating in a quartet to cart the body around; without four rotund tires, the car cannot ride swiftly off down Sunset, regardless of the engine’s desperate rev. Worse, a limping, clunky machine frustrates fulfillment, falling flat on the road to satisfaction.

Fig. 6. Ed Ruscha, Joe’s Car #2, diptych–gelatin silver print, 18 15/16 x 10 11/16 in. (48 x 27 cm.), 1960. The Art Institute of Chicago.

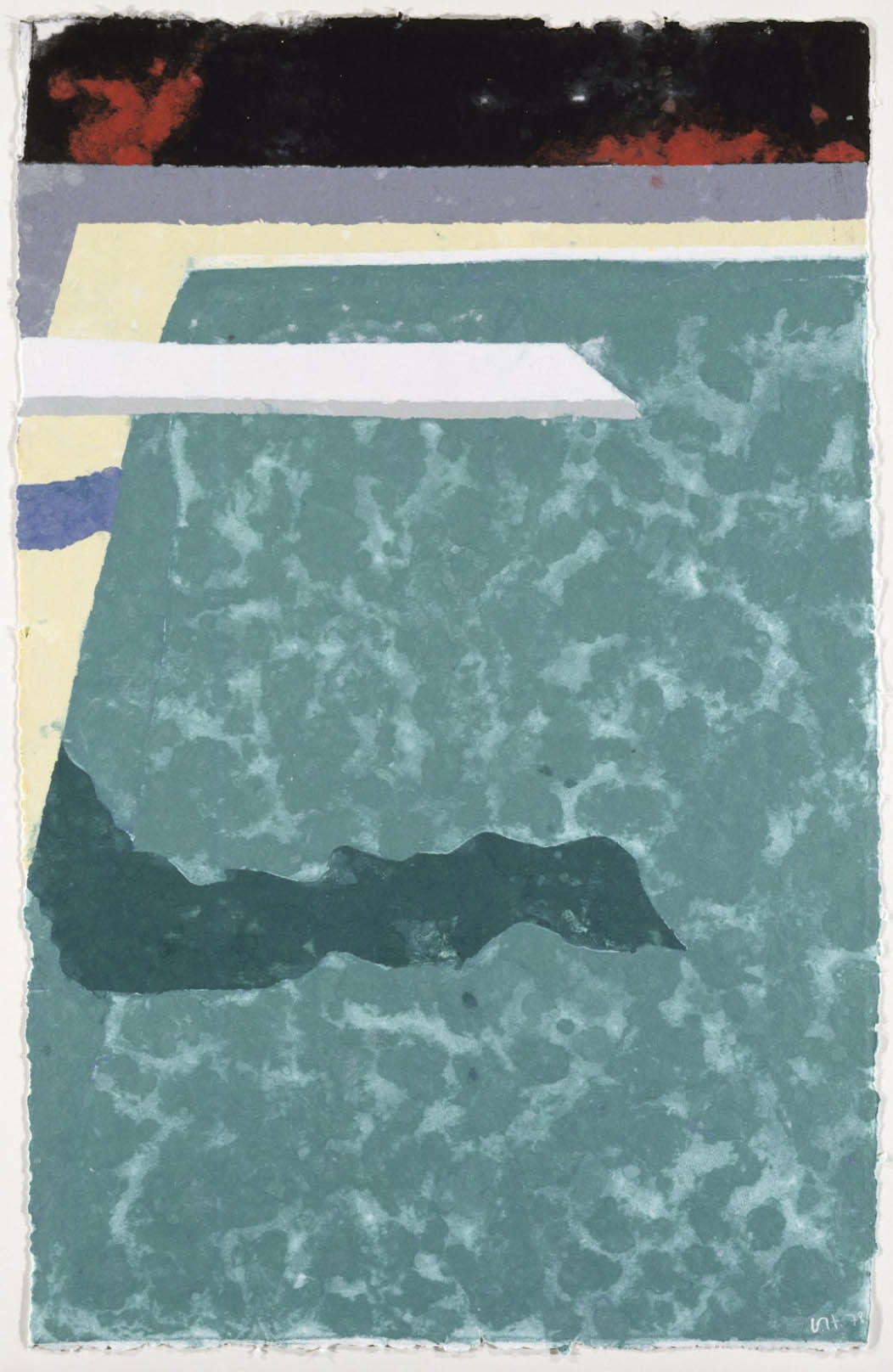

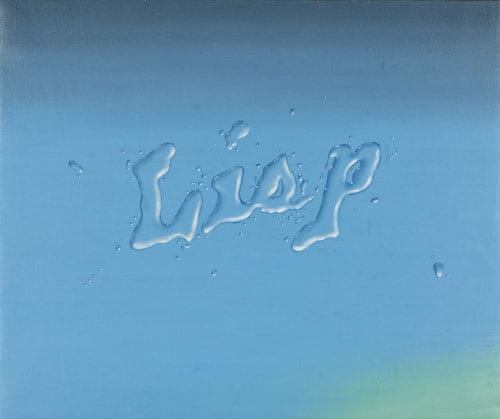

And where exactly lies this lost road? The painting’s palette evokes a sun-lashed, chlorine-saturated, Southern California backyard pool, a color to which David Hockney, another West Coast transplant, would succumb over a decade later in his paper pulp pictures (fig. 7). Suspended in an aquatic daydream, the tire balloons into a windswept inner tube, evicted from all-wheel-drive terrain, while ‘F’, ‘I’, ‘S’, and ‘K’ bob around in anticipation of Ruscha’s liquid word series (1967-69; fig. 8). Bois appropriates the thermodynamic concept of entropy to illustrate the lifespan of one of Ruscha’s oozing, bubbly words, ever melting back into primeval obscurity.[18] Here, the typographically sound letters threaten to obliterate not their individual appearances, but the tentative link binding them together in sequence, thus probing the solidity of ‘FISK’ as a carrier of meaning. Indeed, “as Bois has stressed, Ruscha is no Cratylist–that is, he hardly believes that signs are grounded in the appearance of referents–and yet, as with his onomatopoeic words, he plays on our old belief in such worldly grounding, only then to disturb it, and in doing so to produce more ‘huh?’”[19] These layered histories–of a once thriving, now failing company with a witty slogan, malleable logo, and symbolic product–relay a cautionary tale of bygone corporate deterioration; yet, the resonances chime only upon deeper inquiry into the presented word, which itself is in danger of disintegrating. Lifted from the nostalgic annals of American commercial history, Ruscha’s text both embodies the Pop concern for capitalist critique, by castrating the independent Western spirit and relegating it to submissive impotence, and speculates on the arbitrary connection between image and word, product and brand.

Fig. 7. David Hockney, Green Pool with Diving Board and Shadow (Paper Pool 3), colored and pressed paper pulp, 50 1/2 x 31 7/8 in. (128.3 x 81 cm.), 1978. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Fig. 8. Ed Ruscha, Lisp, oil on canvas, 24 1/2 x 28 1/2 in. (62.2 x 72.4 cm.), 1968. Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University.

While Ruscha often remains equivocal on interpretation, he has rarely been anything but straightforward when speaking of Jasper Johns’s influence. Ruscha enunciates his debt to the older painter, along with Robert Rauschenberg, in markedly acoustic language, attuned to the works’ subtle aural aspects: “It was a voice from nowhere…the kind of odd vocabulary they used…–it was like music that you’ve never heard before, so mysterious and sweet.”[20] In his essay on Johns’s early painted words, Harry Cooper spends considerable time on the enigmatic The (1957; fig. 9).[21] If ever there was precedent for Ruscha’s taking note of the overlooked, it was Johns’s activation of that three-letter word found at least one hundred times in this paper already, yet ever without a point of its own. Cooper describes Johns’s austere composition in a comment that could aptly apply to a Ruscha: “The word is presented in splendid isolation, as it rarely is, as if to arrest our attention on a workhorse of the language, a monosyllable that we take for granted, a word that is always upstaged by the one that follows it.”[22] In the related footnote, Cooper questions whether Johns intended the article to appear as an object in space or actually convey meaning, and distinguishes between “citing the word” and “using it.”[23] Paired with an object that clarifies its meaning, ‘FISK’ is arguably in use, a title more than a picture, whereas Johns camouflages ‘THE’ within abysmal space, more optical citation than caption.

9. Jasper Johns, The, encaustic on canvas, 24 x 20 in. (61 x 50.8 cm.), 1957. Private collection.

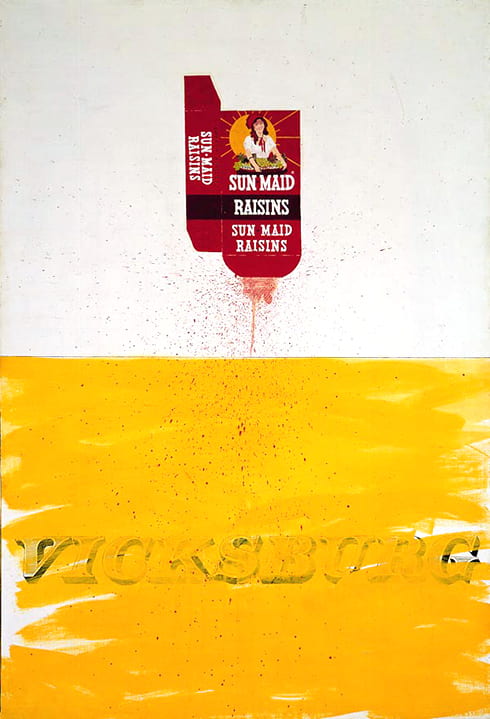

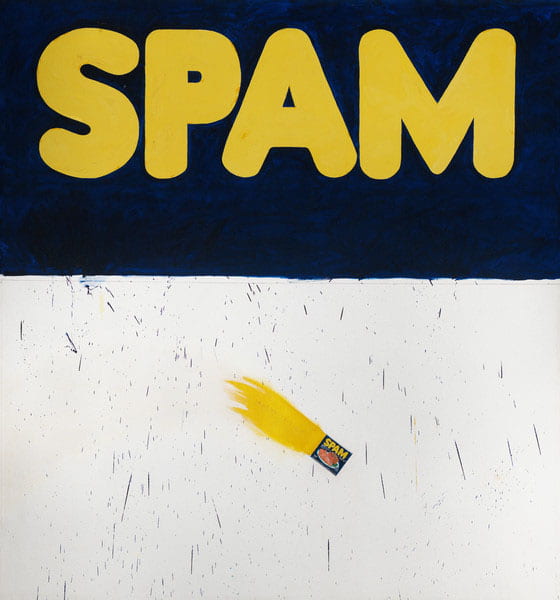

Unlike Johns’s work, however, Ruscha’s does not take the title its surface implies–or at least not always. The catalogue raisonné publishes the present painting as Falling, But Frozen (Fisk). The editor, Pat Poncy, also reports the presence of an artist inscription: “titled and dated ‘Falling But Frozen 1962’ verso upper left in pencil; titled and dated ‘Falling But Frozen July 1962’ verso on horizontal crossbar.”[24] Despite evidence twice-over from the artist’s hand as to the correct title, Poncy inserts a comma and a parenthetical into the official record. (Subsequent publications of the work primarily follow the artist’s notation, while a 2001 auction appearance elided the comma but kept the parenthetical.) Curiously, Poncy exercises similar editorial control in the publication of Box Smashed Flat (Vicksburg) (1960-61; fig. 10), one of the other two pictures included in the 1962 show, whose crossbar inscription reportedly reads “Package Smashed Flat”; ‘Vicksburg’ is only visible on the recto lower register and nowhere on the verso.[25] The third painting in the show, Actual Size (1962; fig. 11), features the brand name ‘SPAM’ twice–once on its own in the upper register, and again on its product label zooming through the lower–yet Poncy refrains from any parenthetical at all.[26] The assigned title is less discernible, scribbled into the falling Spam can’s backdraft.

Fig. 10. Ed Ruscha, Box Smashed Flat (Vicksburg), oil and ink on canvas, 70 x 48 in. (177.8 x 121.9 cm.), 1960-61. Museum Ludwig, Cologne.

Fig. 11. Ed Ruscha, Actual Size, oil on canvas, 71 3/4 x 67 in. (182.2 x 170.2 cm.), 1962. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Though the semantics vex, clarity on how best to refer to these works directs how to see the relationships therein, as suggested both by Cooper’s similar quandary with Johns, and, the scrupulous attention to naming conventions from scholars like Stephen Bann and John Fisher.[27] Per E. H. Gombrich: “Unlike images, language can make that vital distinction…between universals and particulars…language can specify, images cannot.”[28] But what does the painting’s title specify precisely, other than an ambiguous contradiction? For an object can only be simultaneously falling and frozen within the virtual space of the canvas– never in the physical world. Within the picture plane, ‘FISK’ specifies a type of tire, rather than a universal symbol of mobility; if ‘FISK’ is also part of the title, then it doubly describes the thing frozen in its fall. However, if the name of the painting excludes the presented word, then it and its shaped parts become formal elements equivalent to the schematic tire–‘F’, ‘I’, ‘S’, and ‘K’ also fall subject to Ruscha’s impossible gravity. In fact, the depiction of the letters and the tire with graphite and negative space, rather than the vibrant, tactile oil of the foreground, reinforces their status as literally empty shapes, both formally and conceptually. Only together do the five uncolored elements encode meaning–at the level of signifier, they comprise an inventory of common objects (one tire, four letters); at the level of signified, a recognizable brand.

In her discussion of the Pasadena Ruschas, Pasquariello asserts that “the full eclipse of the commodity by the commodity name that was coming to characterize post-war American consumerism and advertising is not depicted,” claiming instead that the presence of a referent object prohibits the complete subsumption of product into brand.[29] However, the very bastardization of those objects–the functionless tire, structure-less raisin carton, and anchor-less Spam can–actually strengthens the increasing reliance on text alone to communicate operative value, underscored by Ruscha’s imminent elision of the object from his practice entirely. And if the brand is rapidly overtaking the product to the extent of wholesale substitution, then, in Falling But Frozen, Ruscha crafts a verbal/visual redundancy–Fisk is the tire, the tire is Fisk. Contrary to the other two Pasadena pictures, Ruscha places the brand proximate to the object but does not emblazon it. In doing so, he tests the strength of the arbitrary union between definition and defined, and finds that, even separated, the precariously connected sign and signified retain synonymy in the conditioned mind of the beholder.

Brand identification with the object of its production appeals to the base, visual part of the brain and thus resurrects the earliest iterations of language: pictograms and hieroglyphs or ideas represented by schematically mimetic signs. By returning to simple visuals, this semiotic method circumvents the ability to reason in the abstract that an objective, independent alphabet makes possible, as Marshall McLuhan and R. K. Logan contend, thereby wresting rational power from the seer (or consumer).[30] Everything an image of a tire could communicate to a mobile society is now inscribed in those four, meaningless letters; inversely, those letters are no longer meaningless when paired with a visual cue. Michel Foucault rightly predicted that “a day will come when, by means of similitude relayed indefinitely along the length of a series, the image itself, along with the name it bears, will lose its identity.”[31] The critical distance between text and image thus collapsed, the contemporary viewer re-enters a pictures-ruled realm, delivered there by language.

If language is the linchpin, then articulation is key. Cooper’s struggle to gain purchase on pronunciation in Johns’s painting exemplifies a crucial point–any aural effect of a pictured word necessarily relies on the thinking spectator’s participation. Indeed, “we cannot look at [the] without resolving those three letters into a word, without reading them, which means we must decide how to read them.”[32] Cooper’s repetition of the first person plural pronoun emphasizes the cooperative engagement an image of language requires. The framework for representation is shared vocabulary–to understand, we translate. In the act of translation inheres a performative aspect, whether the mental substitution of one signifier for another, or the verbal ‘sounding out’ of the text. Ruscha exerts a similar participatory imperative over his viewer, which subsequently elicits auditory free associations. Mistaking ‘FISK’ for ‘disk,’ ‘risk,’ or ‘fist,’ for example, inevitably alters the reading of the tire and thereby indulges the constant specter of slippage between word and meaning. Thus, Ruscha’s intense scrutiny, beyond shining light on the frequently overshadowed, also exposes the precariousness of language–a simple sonic change morphs a forceful icon of American economic domination (‘FISK’) into the enemy of its stability and, ultimately, the arbiter of its destruction (‘risk’). Put another way by critic Dave Hickey, we are always just one letter away from writing (with) ‘worms’ instead of ‘words.’[33] In his juxtaposition of a linguistic artifact from expended culture with the deflated symbol it once encoded, Ruscha challenges the arbitrary link between sign and signified. His skewed scale, playful palette, and mismatched materials further this ambiguous relationship and confound a traditional reading of Falling But Frozen as just another product of perfunctory Pop.

With one turn of the wheel, Ruscha sets in motion a spiraling vortex of associations; he allows each element of his design enough space for isolated analysis before slamming them back together in a synthesis of formal pictorial strategy and mass media subversion. For an artist with an overflowing shelf of his own books, it is remarkable how all the words seem to have fled the bindings for the canvas. As if witnessing this exodus, Ruscha admits a predatory instinct: “Words have temperatures to me…[u]sually I catch them before they get too hot.”[34] Attracted to the warm wordy flesh of an omnivorous Anglophone society, Ruscha finds himself caught up in a collective web of signs and signifiers, catching linguistic shreds as they fall from lips, and capturing conversations to freeze them in time and space. Thus, Ruscha’s common objects are ever falling from consciousness, but forever frozen in memory–caught on canvas, where the artist indiscriminately dismembers otherwise blissfully oblivious verbal/visual constructions.

“A Conversation Between Walter Hopps and Edward Ruscha, who have known each other since the early 1960s, took place on September 26, 1992.” In Edward Ruscha: Romance with Liquids, 97-108. New York: Gagosian Gallery and Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1993.

Bann, Stephen. “The mythical conception is the name: Titles and names in modern and post-modern painting.” Word & Image 1, no. 2 (Spring 1985): 176-89.

Blistène, Bernard. “Conversation with Ed Ruscha.” In Leave Any Information at the Signal:

Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages by Ed Ruscha, edited by Alexandra Schwartz, 300-08. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 2002.

Bois, Yve-Alain. “Intelligence Generator.” In Edward Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, Volume One: 1958-1970, edited by Pat Poncy, 5-13. New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2003.

–––––––. “Thermometers Should Last Forever.” OCTOBER 111 (Winter 2005): 60-80.

Cooper, Harry. “Speak, Painting: Word and Device in Early Johns.” OCTOBER 127 (Winter 2009): 49-76.

Coplans, John. “Letters: Common Denominator.” Artforum 41, no. 5 (January 2003): 8.

Deleuze, Gilles. “Foucault: Lecture 13, 25 February 1986.” Edited by Charles J. Stivale and translated by Christopher Penfield. Purdue University Research Repository. doi:10.4231/R7G15Z2Q.

Failing, Patricia. “Ed Ruscha, Young Artist: Dead Serious About Being Nonsensical.” In Leave

Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages by Ed Ruscha, edited by Alexandra Schwartz, 225-37. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 2002.

Fisher, John. “Entitling.” Critical Inquiry 11, no. 2 (December 1984): 286-98.

Foster, Hal. “Ed Ruscha, or the Deadpan Image.” In The First Pop Age: Painting and

Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, and Ruscha, 210-47. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Foucault, Michel. This Is Not a Pipe. Translated and edited by James Harkness. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Gombrich, E. H. “Image and Word in Twentieth-Century Art.” Word & Image 1, no. 3 (Summer 1985): 213-41.

Hickey, Dave. “Wacky Molière Lines: A Listener’s Guide to Ed-werd Rew-shay.” Parkett 18 (December 1988): 28-47.

Karlstrom, Paul. “Interview with Edward Ruscha in His Western Avenue, Hollywood Studio.” In

Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages by Ed Ruscha, edited by Alexandra Schwartz, 92-209. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 2002.

McLuhan, Marshall, and R. K. Logan. “Alphabet, Mother of Invention.” ETC: A Review of

General Semantics 34, no. 4 (December 1977): 373-83.

Medrano-Bigas, Pau. “Fisk Tires and the Sleepy Boy.” In The Forgotten Years of Bibendum,

Michelin’s American Period in Milltown: Design, Illustration and Advertising by Pioneer Tire Companies (1900-1930), 1897-980. Doctoral dissertation. University of Barcelona, 2015 [English translation, 2018].

Pasquariello, Lisa. “Ed Ruscha and the Language That He Used.” OCTOBER 111 (Winter 2005): 81-106.

Pindell, Howardena. “Words with Ruscha.” In Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages by Ed Ruscha, edited by Alexandra Schwartz, 55-63. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 2002.

Poncy, Pat, ed. Edward Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, Volume One: 1958-1970. New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2003.

Richards, Mary. Ed Ruscha. London: Tate Publishing, 2008.

Schwartz, Alexandra, ed. Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages by Ed Ruscha. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 2002.

“Stockholders Vote Fisk Rubber Sale.” New York Times, December 30, 1939.

“Street Talk with Ed Ruscha: Venice, California, November 11, 2009.” In Ed Ruscha: Road.

Tested, edited by Michael Auping, 47-53. Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2011.

[1] Ed Ruscha in Paul Karlstrom, “Interview with Edward Ruscha in His Western Avenue, Hollywood Studio,” California Oral History Project, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, October 29, 1980; March 25, 1981; July 16, 1981; October 2, 1981; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages by Ed Ruscha, ed. Alexandra Schwartz (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 2002), 189.

[2] Ruscha in Karlstrom, “Interview”; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 153.

[3] Ruscha in Karlstrom, “Interview”; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 190.

[4] Lisa Pasquariello, “Ed Ruscha and the Language That He Used,” OCTOBER 111 (Winter 2005): 82.

[5] Ruscha in Howardena Pindell, “Words with Ruscha,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter 3, no. 6 (January-February 1973): 125-28; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 56.

[6] Ruscha in Karlstrom, “Interview”; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 103.

[7] Yve-Alain Bois, “Intelligence Generator,” in Edward Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, Volume One: 1958-1970, ed. Pat Poncy (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2003), 10.

[8] Mary Richards, Ed Ruscha (London: Tate Publishing, 2008), 15; “A Conversation Between Walter Hopps and Edward Ruscha, who have known each other since the early 1960s, took place on September 26, 1992,” in Edward Ruscha: Romance with Liquids (New York: Gagosian Gallery and Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1993), 98-99. A separate firsthand account has Hopps dictating the direction (John Coplans, “Letters: Common Denominator,” Artforum 41, no. 5 (January 2003): 8).

[9] Ruscha in Bernard Blistène, “Conversation with Ed Ruscha,” in Edward Ruscha: Paintings/Schilderijen (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1990), 126-40; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 301.

[10] Poncy, Catalogue Raisonné, 62.

[11] Ruscha in Patricia Failing, “Ed Ruscha, Young Artist: Dead Serious About Being Nonsensical,” ArtNews 81, no. 4 (April 1982): 74-81; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 231.

[12] Ruscha, “Studio notebook entry, 1962,” in Poncy, Catalogue Raisonné, 58-59. The notes reference Radio (1962).

[13] “Stockholders Vote Fisk Rubber Sale,” New York Times, December 30, 1939, B19.

[14] For a robust history of the Fisk Rubber Co. and its imagery, see Pau Medrano-Bigas, “Fisk Tires and the Sleepy Boy,” The Forgotten Years of Bibendum, Michelin’s American Period in Milltown: Design, Illustration and Advertising by Pioneer Tire Companies (1900-1930) (Doctoral diss., University of Barcelona, 2015 [English translation, 2018]), 1897-980.

[15] “If I do a painting of a pencil or magazine or fly or pills, I feel some sort of responsibility to paint them natural size – I get out the ruler” (Ruscha in Failing, “Ed Ruscha, Young Artist”; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 231).

[16] Gilles Deleuze, “Foucault: Lecture 13, 25 February 1986,” ed. Charles J. Stivale and trans. Christopher Penfield, Purdue University Research Repository, doi:10.4231/R7G15Z2Q.

[17] Ruscha in “Street Talk with Ed Ruscha: Venice, California, November 11, 2009” in Ed Ruscha: Road Tested, ed. Michael Auping (Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2011), 47.

[18] Yve-Alain Bois, “Thermometers Should Last Forever,” in Romance with Liquids, 8-38; reprinted in OCTOBER 111 (Winter 2005), 60-80.

[19] Hal Foster, “Ed Ruscha, or the Deadpan Image,” in The First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, and Ruscha (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2012), 216.

[20] Ruscha in Karlstrom, “Interview”; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 116-17.

[21] Harry Cooper, “Speak, Painting: Word and Device in Early Johns,” OCTOBER 127 (Winter 2009): 64-67.

[22] Cooper, “Speak, Painting,” 65.

[23] Cooper, “Speak, Painting,” 65n25.

[24] Poncy, Catalogue Raisonné, 62.

[25] Poncy, Catalogue Raisonné, 40, emphasis added.

[26] Poncy, Catalogue Raisonné, 66.

[27] Stephen Bann, “The mythical conception is the name: Titles and names in modern and post-modern painting,” Word & Image 1, no. 2 (Spring 1985): 176-89; John Fisher, “Entitling,” Critical Inquiry 11, no. 2 (December 1984): 286-98. The latter’s elegant statement on titles pertains well to Ruscha: “…they tell us how to look at a work, how to listen” (Fisher, “Entitling,” 292).

[28] E. H. Gombrich, “Image and Word in Twentieth-Century Art,” Word & Image 1, no. 3 (Summer 1985): 220.

[29] Pasquariello, “Ed Ruscha,” 94, emphasis added.

[30] Marshall McLuhan and R. K. Logan, “Alphabet, Mother of Invention,” ETC: A Review of General Semantics 34, no. 4 (December 1977): 373-83.

[31] Michel Foucault, This Is Not a Pipe, trans. and ed. James Harkness (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 54.

[32] Cooper, “Speak, Painting,” 65.

[33] This comment reformulates Pasquariello’s reading of Hickey’s analysis of Ruscha’s bird paintings, in which Hickey confesses a hunch that “the early bird paintings [are] the product of some rhyming slang, like ‘birds + worms = words,’ creating not real birds but birds as words who ‘sign’ rather than ‘sing’…” (Dave Hickey, “Wacky Molière Lines: A Listener’s Guide to Ed-werd Rew-shay,” Parkett 18 (December 1988): 33; Pasquariello, “Ed Ruscha,” 104).

[34] Ruscha in Pindell, “Words with Ruscha”; reprinted in Leave Any Information at the Signal, 57, emphasis added.

Meghan Doyle is a second-year Master’s student at the Institute of Fine Arts, where she focuses on the collage aesthetic in artist collectives of the post-war United States and, more broadly, the embodied experience of the group exhibition space. Meghan graduated summa cum laude from Pepperdine University in 2018, with BAs in Art History and Italian, where she worked at the Weisman Museum of Art and contributed research to a recently published textbook on global art history. She has also held positions at the British Museum, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and in Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art department, where she played a pivotal role in bringing digital art to the forefront.

Princeton University

In the late 1640s, Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione produced two series of etchings, later referred to as Oriental Heads, which depict bust portraits of various figures in exotic headgear. The prints represent a hitherto unacknowledged aspect of the artist’s identity: his self-fashioned Genoese persona crafted through foreign costume. While previous scholarship has dismissed the etchings as mere emblems of Castiglione’s familiarity with foreign merchants due to his Genoese origins, the present project instead emphasizes the mobility of the prints themselves. Contrary to previous assumptions, Castiglione’s etchings of so-called “Oriental” costumed figures would have been distributed if not originally printed in Rome, where an active market for prints thrived. Upon departure from the port city, when Castiglione arrived in Rome, the symbolism of his mode of dress, visible in the etchings and in contemporary accounts of the artist himself, became fully activated, casting Castiglione as distinctly Genoese. The prints circulated as a mechanism to attract potential patrons, encourage buyers to purchase the artist’s other etchings, and above all, for Castiglione to self-fashion his artistic persona as an eccentric figure in the international art center of Rome. In the seventeenth-century Western European imagination, the turbaned figure represented the epitome of alterity: the Ottoman Turk. Castiglione’s artistic identity can be untangled as a web of East-versus-West vestimentary fluidity born out of a port city and translated as exotic within the Roman art market. Castiglione can now be re-cast as a savvy businessman, a theatrical artist with a flair for the dramatic, and a crucial example of how a traveling artist used printed imagery to build a reputation while abroad.

![]()

Travelers visiting Rome in the mid-seventeenth century who wished to buy a souvenir from their journey abroad could purchase any number of prints. Whether a city view, depiction of antiquities, mythological or biblical narrative, the variety of images available in print was vast.[1] One of the countless artists known to have formally published his prints in Rome was Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (1609-1664), a Genoese artist typically associated with pastoral painting and monotype print, though he was also an accomplished etcher.[2] As a printmaker, Castiglione most often depicted allegorical subjects, biblical narratives, and mythological figures; however, in the mid-1640s, he produced two series of small etchings of anonymous figures in exotic costume, presenting a striking divergence from his typical work.

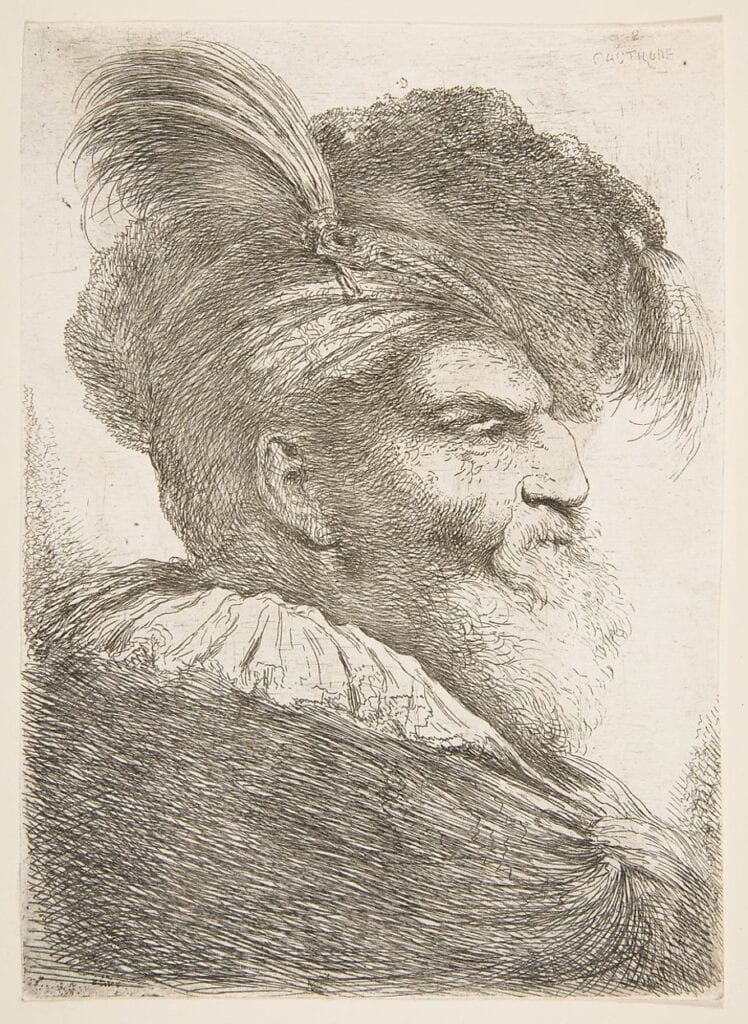

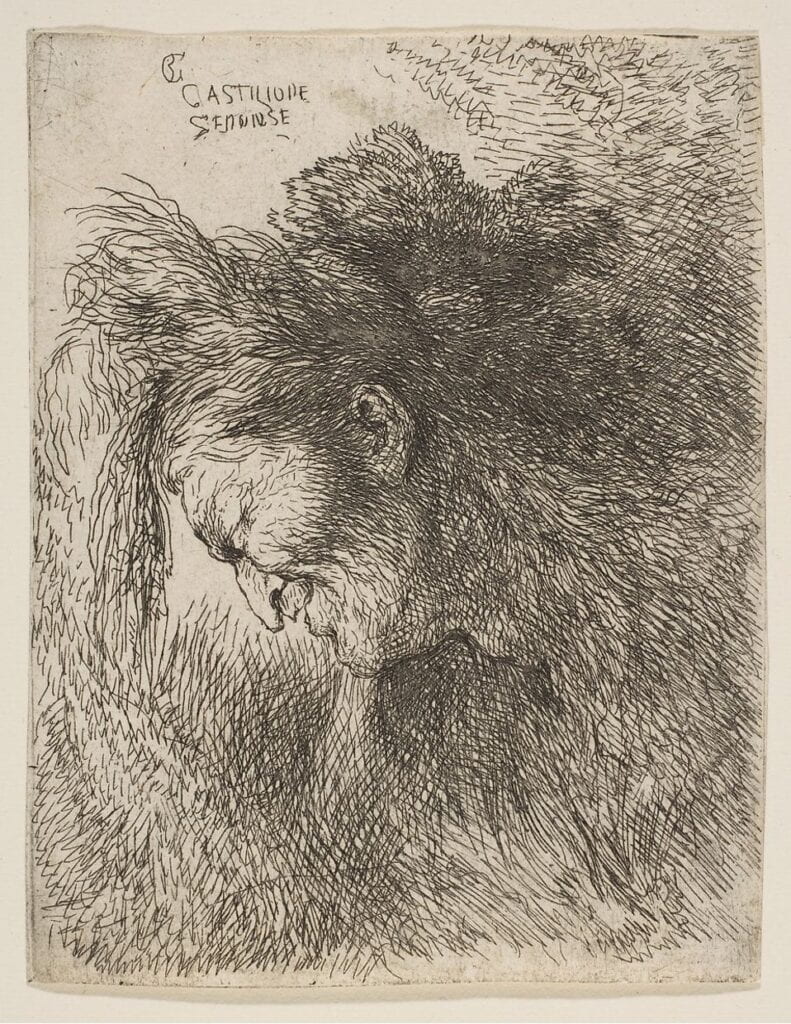

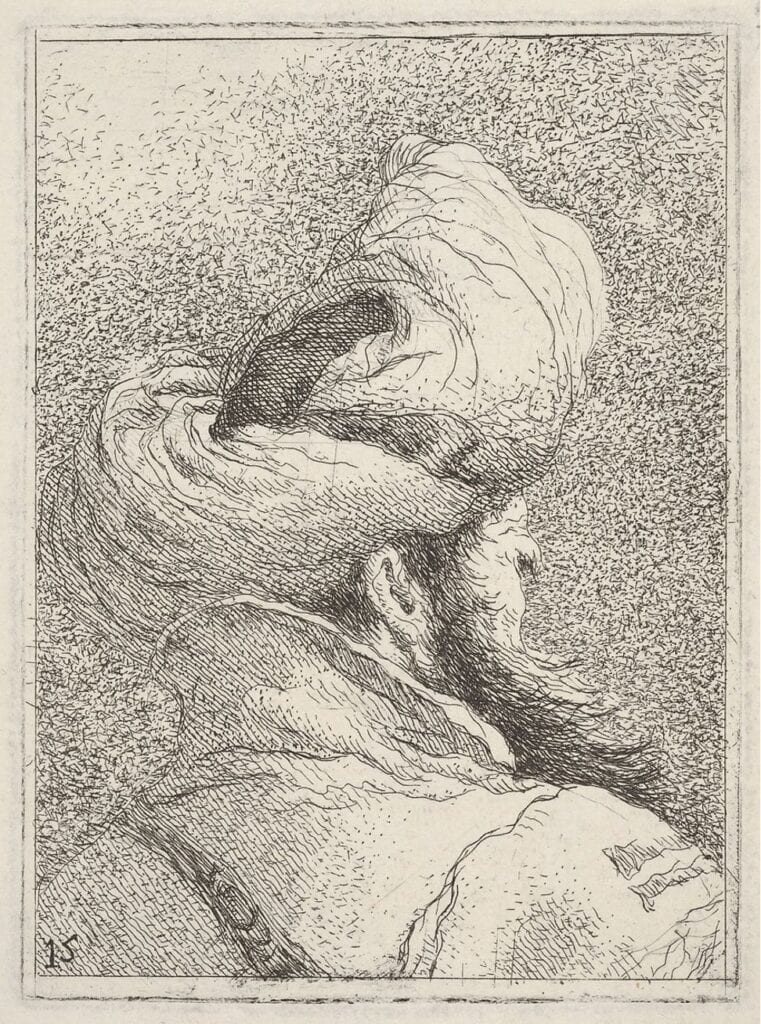

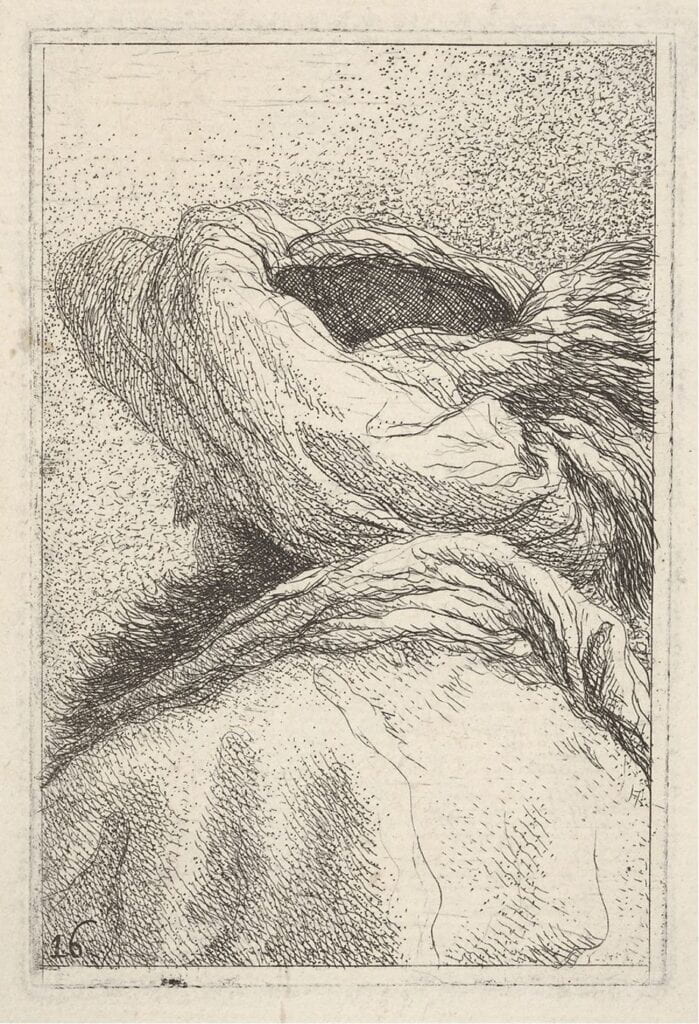

Later referred to by historians as Oriental Heads, Castiglione’s two[3] series of small-scale etchings of “Oriental” busts depict seemingly exotic individuals, whose foreign identities are indicated by their costumes: feathered caps (fig. 1), jeweled headdresses (fig. 2), turbans (fig. 3), and floppy caps (fig. 4). The figures are primarily old, even elderly men (fig. 5), though Castiglione provided variety by including young men, as well as one woman. The figures’ faces are highly individualized, as if they could have been real recognizable people in the seventeenth century. Nearly all of the etchings in the two series are signed “Castiglione, Genovese,” making the artist’s identity an unavoidable aspect of the print series. The prints comprise a largely ignored part of Castiglione’s oeuvre, and in fact offer important insight into early modern perceptions of the exotic East, self-fashioned artistic identity, and more broadly, they begin to answer the question of what is meant to be seen as distinctly Genoese in the mid-seventeenth century. These issues are the central pursuit of the present paper.

Figure 1. Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, Head of a bearded man with a turban facing right, from the Small Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-1650, etching. Sheet: 4 5/16 × 1 15/16 in. (11 × 5 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 2. G. B. Castiglione, Head of an old man facing right, from the Large Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-1650, etching. Sheet: 7 3/8 x 5 1/4 in. (18.7 x 13.4 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 3. G. B. Castiglione, Man wearing a turban, a tie fastened around his neck facing left, from the Small Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-1650, etching. Sheet: 8 7/16 × 5 7/8 in. (21.5 × 15 cm) Plate: 4 5/16 × 3 1/4 in. (11 × 8.3 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 4. G. B. Castiglione, Young man with a trumpet facing left, from the Small Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-1650, etching. Sheet: 4 5/16 × 3 3/8 in. (11 × 8.5 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 5. G. B. Castiglione, Head of an old man looking down facing Left, from the Small Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-1650, etching. Sheet: 4 1/8 × 3 1/8 in. (10.5 × 8 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

So far, little sustained scholarship exists on the prints at hand. Anthony Blunt argued that the Oriental Heads were directly based on Rembrandt’s tronies, despite the fact that none of the etchings are exact copies.[4] Scholars at times refer to Castiglione as a “second Rembrandt,” specifically in relation to his etchings, citing the stylistic parallels between the two artists. The sketchy lines, dark cross-hatching, and the similarities in subject matter between Castiglione’s Oriental Heads and Rembrandt’s countless depictions of Oriental figures are more than enough to explain this nickname. However, this nickname does not explicate that Castiglione almost certainly was exposed to Rembrandt’s prints during his lifetime. The emulation of Rembrandt’s style was probably completely intentional, suggesting that the artist wanted to align himself with the broad appeal of his Dutch contemporary.

Timothy Standring moved beyond this comparison, arguing that Castiglione’s hometown of Genoa was the true inspiration behind the series, which would have allowed the artist opportunities to observe foreign merchants in exotic dress.[5] While this may indeed have been the case, neither Standring nor Blunt engaged with issues of the distribution and reception of the prints. While both arguments certainly have merits, this project takes these ideas several steps further and seeks a better understanding of the artistic, social, and historical conditions under which Castiglione produced the busts.

A closer examination of these prints helps reconstruct the world of a traveling artist from a port city in seicento Italy. The Oriental Heads were likely distributed (if not printed) during Castiglione’s time spent in Rome in the mid-1640s, and as such, can be understood as a strategic way for Castiglione to earn a small profit and to advertise his artistic skill in the hopes of earning future commissions from Roman patrons.[6] This drastically changes the way the prints should be read in terms of their perception, demanding a deeper consideration of how Castiglione presented himself as a professional Genoese artist while abroad. In this context, the etchings open up several questions, such as the extent to which Castiglione’s emulation of Rembrandt would have been understood by viewers at the time. The depiction of exotic Eastern costume throughout the series in question suggests that Castiglione sought to present his artistic image in the context of foreign costume, evoking images of Ottoman Turks. By fusing his Genoese identity with the idea of the Eastern Mediterranean world vis-a-vis the Oriental Heads, Castiglione aimed to self-fashion his artistic persona within the confines of the Roman art market.

Castiglione in Rome

Despite the fact that no known documentation survives that can firmly attest to the distribution of the Oriental Heads in Rome, substantial evidence supports this context. Castiglione is known to have been in Rome during the 1640s when he published multiple prints under the De Rossi Publishing company. These include Diogenes Searching for an Honest Man (fig. 6) and The Genius of Castiglione (fig. 7), the latter of which was published in 1648. During his time spent in Rome, Castiglione worked more extensively in etching than in any other medium, and Paolo Bellini argued that the Heads were probably created in Rome around 1648.[7] However, we have no indication that they were formally published, since the De Rossi inscription does not appear on any of the extant editions, nor do they appear in the De Rossi archives, the only publishing house to which Castiglione can be firmly connected.[8]

Figure 6. G. B. Castiglione, Diogenes Searching for an Honest Man, c. 1645-1647, etching, 8 7/16 x 11 15/16 in. (21.5 x 30.4 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 7. G. B. Castiglione. The Genius of Castiglione, ca. 1645-47 (published 1648), etching, 14 x 9 5/8 in. (35.5 x 24.5 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A stylistic analysis of the etchings would suggest that they probably date to the mid-1640s. One of the most remarkable aspects of the etchings is the nuance with which Castiglione treats light and shadow. For instance, in his depiction of a Young Man looking down to the right (fig. 8), he was familiar enough with etching to create dramatic shadows while still revealing individualized facial features. Throughout the series, Castiglione masterfully employs negative space to imply form and plasticity, while background shadows fan out to fuzzy tendrils along the borders.

Figure 8. G. B. Castiglione, A young man looking down to the right, from the Small Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-50, etching, Sheet: 8 1/4 × 5 3/4 in. (21 × 14.6 cm), Plate: 4 5/16 × 3 1/8 in. (11 × 8 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The singular image of a woman (fig. 9) in the series exemplifies his characteristic use of wavy lines, as the shadows echo the plume of the sitter’s headdress. Castiglione’s earlier etchings lack this subtle treatment of volume and shadow, as evident in Laban searching for idols among Jacob’s possessions (fig. 10) from the late 1630s, which is more characteristic of the artist’s earlier experimentation with etching. The print of Laban is flatter in composition, with the figures drawn together towards the foreground and shadows indicated by many short, straight strokes and cross-hatching. The parallel lines in the sky are uniform and neat, a stark contrast to the organized chaos of the shadows seen in the Oriental Heads. The series in question is indicative of an artist who had become confident in his manipulation of the etching needle in such a way that he could toy with the limits of the media. Dark areas become blacker, while the borders of his figures glisten between plastic form and imagination, as can be seen in the print of an old bearded man (fig. 11), in which an image of a horse’s head is hidden in the figure’s cloak and a portrait in profile in the upper left forces the viewer to closely examine the print to engage with these delights. This range of technical skill is far more similar to the later published etchings, supporting a dating to after 1645.

Fig. 9. G. B. Castiglione, Young woman wearing a plumed turban, from Small Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-1650, etching. 4 5/16 × 3 1/8 in. (11 × 8 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 10. G. B. Castiglione, Laban searching for idols among Jacob’s possessions, ca. 1635-1640, etching. Sheet: 9 15/16 x 13 1/16 in. (25.3 x 33.2 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 11. G. B. Castiglione. Head of an old bearded man with a turban, from Small Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-1650, etching. 4 5/16 × 3 1/8 in. (11 × 8 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Another notable aspect of the Heads is the repeated inclusion of the artist’s signature. All the etchings are signed “Castiglione,” but most read “Castiglione, Genovese,” or “Castiglione Genovese FE.” The signature including a place name is crucial because the artist is known to have used this signature style specifically when abroad, while the bulk of his works created in Genoa are only signed “Castiglione”.[9] By the time the prints were made, Castiglione had long been known as a successful painter around the port city, having garnered several private and religious commissions, none of which included a place name in his signature. Connecting one’s identity to a place name was a common practice in the early modern period, evidenced by the array of artists who signed their work in this manner and by the Vite literature of the period. For example, Raffaello Soprani’s 1674 Le Vite de’ Pittori, Scultori ed Architetti Genovesi is divided between “Genovesi” artists and “forastieri” working in Genoa, suggesting a strong connection between place names and artistic identity in the mid-seventeenth century. Local attachments had also appeared in earlier biographies, such as Vasari’s Vite, which consistently notes artists’ hometowns and the locations to which they traveled throughout their careers.[10]

The specific method of signature, coupled with the stylistic evolution of Castiglione’s etchings, firmly establishes that the Oriental Heads were most likely distributed while Castiglione was in Rome in the late 1640s and were intended for a distinctly Roman audience. This demands a re-consideration of the prints in terms of the Roman art market, rather than a Genoese context alone, as Standring suggested. The image presented through the Oriental Heads is built on the idea of Ottoman Turks as simultaneously terrifying military antagonists and as fascinating, mysterious foreigners; at the same time, the close connections between Genoese and Northern European artists and Castiglione’s technical virtuosity would have appealed to the intended Roman audience.

Oriental Costume in Seicento Rome

Beyond the range of technical skills Castiglione demonstrated in the Heads series, the only feature that ties the series together is the subject: bust portraits in exotic costume. This raises the question of why this subject would have been chosen in a series intended to spread and promote the artist’s image abroad. As Jacob Burckhardt famously argued, one of the central aspects of the Italian Renaissance was the “discovery of the outward universe, and … the representation of it in speech and in form.”[11] By the turn of the sixteenth century, printed imagery related to foreign places had exploded, especially in the realm of print. Costume books purporting to show people of the entire world, as well as maps, atlases, and city views, all speak to the increased attention devoted to depictions of the wider world, and to what Ayesha Ramachandran has called “worldmaking”: the process by which early modern Europeans came to understand the wider world and their place in it.[12] Within these processes, specific loci emerged as places of particular fascination, often on the basis of political antagonism, trade, colonial expansion, and/or cultural or racial alterity. The Ottoman Empire was one of the most popular spaces in this context, and such interest is reflected in the world of sixteenth-century Italian print, long before Castiglione arrived on the scene.

Ottoman costume itself became a primary area of interest, and there were even entire costume books devoted specifically to the Ottomans. These costume books contained images of stereotypical garb, often copied from other earlier costume books, though they could be presented as first-hand observation. For example, Nicolas de Nicolay’s Quatre premier livres des navigation from 1567 depicted scenes based on the author’s time spent at the Sultan’s court in Istanbul, where he traveled as a diplomat in 1551. Nicolay’s book later became an important model for other costume plates, such as those found in the work of Cesare Vecellio, who published one of the largest volumes on “global” costume in the sixteenth century. In fact, costume books remained important sources for seventeenth-century artists too; for example, Stefano della Bella, a contemporary of Castiglione, copied and adapted plates from Melchior Lorck’s costume book in his drawings of theatrical ceremonial entrances.[13] However, none of Castiglione’s Oriental Heads etchings can be specifically connected to a costume book, suggesting that they were either drawn from life, or (more likely) were invenzioni. Della Bella too produced bust portrait etchings of Ottoman Turks, though they were typically groups of multiple figures rather than individuals like Castiglione’s, and the same sitters often appear elsewhere in della Bella’s oeuvre, suggesting that for him, the bust portrait of foreign figures could have been an interesting subject of study, or a way to earn a profit by replicating such exotic figures in multiple plates.

In addition to costume books, printed literature portraying Ottomans expanded, especially towards the end of the wars between the Papal States and the Ottoman Empire, culminating with a decisive defeat of the Ottomans at Lepanto in 1571, after which point, Ottoman expansion became less of a concern for Italians (though warfare with the Holy Roman Empire continued well into the late seventeenth century).[14] Artistic depictions of Ottomans proliferated in Italy, as well as in Northern Europe, and over the course of the sixteenth century, the figure of the Ottoman Turk became a mythologized, exaggerated synonym of a kind of Antichrist, particularly during the years of active warfare between East and West.[15] In opposition to the notion of direct observation set forth in works like Nicolay’s costume book, other images like Dürer’s apocalyptic prints distill the image of Ottoman costume to simple elements: most iconically, turbans. Through this process of simplification, images of turbaned figures eventually became synonymous with Ottoman Turks more generally, and all that they represented in the European imagination.[16]

For the sixteenth-century Roman viewer, the image of the Turk invoked fear of the expansion of the Ottomans and, thus, the expansion of Islam itself through violent militaristic conflict. At the same time, Turks were viewed as barbarians, an uncivilized nomadic people whose heresy was evident in their hedonism and in their fearsome traditions, allegedly including cannibalism and other brutalities.[17] However, by the mid-seventeenth century, warfare between the Papacy and the Ottomans was essentially over, and Ottoman costume imagery too became less fearsome. Instead, it could evoke ideas of luxury, exoticism, and a less fearsome brand of barbarism for the Roman viewer. It was to this long history of images of Ottomans that Castiglione’s prints belonged. For Castiglione, images of Ottoman costume, portrayed namely through headdresses, functioned as imagined, Eurocentric symbols of the Ottoman Turk, crafted by a European for a European audience. Images of exotic headdresses had long functioned in this way. Castiglione, like so many others before him, revealed his use of what Roland Barthes calls a “vestimentary system,” in which the language of clothing reveals complex historical messages, which can be deciphered through a close examination of costume.[18] The symbolic content of Castiglione’s images of so-called “Oriental” costumes is thus more potent than they might initially appear.

Castiglione’s Genoese identity made Oriental (Ottoman) costume a perfectly suited subject. Genoa had long-standing economic ties with the Ottomans, but also became seen as a bulwark against the threat of Ottoman expansion. During the Middle Ages, Genoa earned a reputation as a powerful trade center, both through imports and exports. During the fourteenth century, Genoa established ports throughout the islands of the coast of Anatolia, as well as on the mainland, including posts at Chios, Lesbos, and Phocaea.[19] As the Ottoman Empire expanded in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, these Genoese ports eventually all fell under Ottoman control.[20] Just as Venice developed an intimate connection with the East through trade, the Republic of Genoa relied heavily upon its relationship with Ottoman traders to thrive economically. In addition, Castiglione probably would have seen Ottoman traders circulating around the port of Genoa at least on occasion while he lived there, giving his portrayal of the subject a certain level of authority based on first-hand observation.

However, Genoa was also seen as a central player in the ultimate defeat of the threat of Ottoman westward expansion. The Genoese condottiero and ruler Andrea Doria famously fought off Barbary corsairs throughout the Mediterranean and led several battles against the Ottomans from 1540 to 1541; later, Doria served under Pope Paul III’s Holy League, although the Ottomans would defeat the Genoese, Spanish, and French forces in 1544.[21] The general awareness of Andrea Doria’s fight against the Ottomans is attested to by the breadth of literary and artistic depictions that appeared as early as the sixteenth century, including artistic depictions by Bronzino and Baccio Bandinelli, and the writings of Ludovico Ariosto, Ludovico Dolce, and Pietro Aretino.[22] Doria’s defense against pirates and Turks alike earned him a reputation as a powerful leader against the “infidel” and a leader of Genoa itself when he ended the French occupation in 1528. The fame of Andrea Doria throughout the Italian peninsula as a defender of Christianity itself would have solidly established Genoa as a bulwark against Ottoman expansion.

In early modern Genoa, images of Turks appeared in several contexts: frescoes, biblical scenes, history painting, and portraiture. Figures wearing turbans were shorthand for Turkish identity, appearing as enemies (Romans and Jews who crucified Christ), chained captives symbolizing defeated enemy troops, and sometimes as playful costumes worn by Genoese aristocrats.[23] Vanquished Turks appear in monumental historical images such as Luca Cambiaso’s tapestry of the Battle of Lepanto, which depicts defeated Turks bound with their turbans removed, a grave symbol of shame and defeat in Ottoman culture. The turban became a visual symbol of the Ottoman Turk, which referenced notions of historical militaristic animosity, the threat of Islam to the Christian West, and simultaneously, associations with luxurious materiality and fascinating cultural practices.[24] In other words, Castiglione’s depiction of Oriental figures would have been closely associated with his Genoese identity; his authority as a first-hand observer of traders, as well as the widespread reputation of Genoa as a crucial force in the defeat of the Ottomans, meant that a Roman audience would have interpreted the Oriental Heads as reliable images of “real” Turks and as symbols of the European fear of the Ottoman threat.

Castiglione fused the appealing subject matter with varied examples of his technical artistic skill in order to attract these Roman viewers. Castiglione’s Oriental Heads include images of young men, old bearded men, androgynous turbaned figures, and a single etching of a woman. The variation in the figures depicted in the series is not because Castiglione observed many different exotic figures, but was a way for him to create a virtuosic variety throughout the series. The diversity throughout the series allowed Castiglione to flaunt his technical ability as an etcher, while the anonymity of the figures and the persistence of exotic headgear solidify the place the etchings hold in the Western imagination as depictions of Ottoman Turks as generic “Easterners” who constantly captivated the imagination of Western Europeans. Stylistically, the images can also be read in light of the important connection between Genoese and Northern artists, to which this paper now turns.

Northern Artists and Seicento Genoa

The comparison between Castiglione and Rembrandt is important beyond the notion that Castiglione was a copyist; it also demands further consideration as a central node of scholarship on Castiglione and Genoa itself. Castiglione’s inspiration from Rembrandt is most apparent in a sketched study of heads from between 1635 and 1640 (fig. 12). The five heads on the left of the sheet are copies of figures in Rembrandt’s 1636 etching of Christ Before Pilate (fig. 13), clearly demonstrating that Castiglione was directly studying and even copying Rembrandt’s works early in his career.[25] The figure on the right in the furred cap is not a direct copy but is an iteration of an etching by Rembrandt after Jan Lieven from around 1635. The similarities between the two figures are most apparent in the headdresses, both of which are vaguely turban-like but are topped with what might be feathers or fur. Both figures also have small beards and fur capes, although Castiglione’s rendition is less detailed than Rembrandt’s. While the Rembrandt prints that Castiglione worked off of were printed from 1635 to 1636, it is not possible at this time to know how quickly they might have been brought to Italy for Castiglione to study. Nonetheless, this pen and ink drawing in London provides specific evidence of Castiglione’s awareness of Rembrandt in his early career, and thus supports the idea that in some capacity, Rembrandt’s prints traveled to Italy in the mid-seventeenth century, even earlier than other sources might indicate.

Figure 12. G. B. Castiglione, Studies of Heads, ca. 1635-1640, pen and ink with brush and ink. 14.3 x 19.9 cm. RCIN 903944. Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023.

Figure 13. Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Before Pilate: the Large Plate, 1636, Etching, fourth state of five. sheet: 21 3/4 x 17 5/8 in. (55.3 x 44.8 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While the stylistic connection between these two artists is striking, such a time frame would suggest rather startling evidence for the presence of Rembrandt’s works in Italy at such an early date. There is strong evidence for collections of Rembrandt prints in the 1660s, and Baldinucci writes about Rembrandt in 1686, though as Seymour Slive argues, much of Baldinucci’s sources for his biography were likely from an earlier period.[26] For example, Bernhardt Keil, a Danish artist who studied with Rembrandt in the mid-1640s, permanently moved to Rome in 1651, and it was Keil who likely provided Baldinucci with an account of the Night Watch, as only a few Rembrandt paintings were known to be in Italy by the time Baldinucci wrote his biography.[27] Slive’s work demonstrates the popularity of Rembrandt’s etching, especially in the 1660s and afterwards, but his evidence for the presence of Rembrandt etchings in Genoa in the 1630s strictly rests upon the stylistic comparison to Castiglione’s works. Collectors in Italy and France became keenly interested in Rembrandt’s work in the mid-seventeenth century, and a large number of Italian artists greatly admired Rembrandt’s skill as a printmaker.[28] Castiglione, Stefano Della Bella, and Guercino were just a few of the artists directly interested in Rembrandt’s etchings, the latter writing in 1660, “I have seen divers of this printed works which have appeared in these parts which are very fine, engraved in good taste and in a good manner… I frankly deem him to be a great virtuoso.”[29] Clearly, Italian artists admired Rembrandt’s technical abilities following (if not during) Castiglione’s trip to Rome.

However, whether this connection would have been made during Castiglione’s time spent in Rome or earlier while he was still in Genoa is not clear, due to the paucity of sources on his life, travels, and artistic practice. Castiglione’s Oriental Heads etchings are so similar to the pen and ink drawings, both in terms of subject matter and the close study of facial expressions typically associated with Dutch tronies that it can be safely assumed that Castiglione was likely aware of the tradition of Rembrandt’s character heads prior to his printing of the Oriental Heads.

It is entirely possible that Castiglione first became aware of Rembrandt’s work while he was still training in Genoa. Genoa had become an artistic microcosm due to the strong presence of Northern Renaissance and Baroque artists in the city, and the repeated collaborations between Northern and Genoese artists during the early modern period had a powerful impact on the city’s artistic identity. In this context, Castiglione’s emulation of Rembrandt might be read as a leveraging and multiplying of the conventionally understood artistic identity of Genoa. The Genoese routinely interacted with Northern artists, who either traveled to Genoa themselves or received commissions from the Genoese.[30] Anthony Van Dyck spent time in Genoa from 1621 to 1627 and worked with a number of Genoese artists during this time, including Castiglione himself.[31] Perhaps more significant for Castiglione was the influence of Jan Roos, who resided in Genoa from 1616 to 1638 and whose pastoral animal landscape type Castiglione quickly adopted.[32] Genoese clergy commissioned Peter Paul Rubens to paint The Circumcision in 1605 for the Chiesa del Gesù in the heart of the oldest part of the city. As these examples show, the presence of Northern artists in Genoa was an integral part of the Genoese artistic world by the time Castiglione appeared on the scene.

Rembrandt was not the only artist who had a lasting impact on Castiglione’s work. Early in his career, Castiglione studied under Giovanni Battista Paggi and later under Anthony Van Dyck and Sinibaldo Scorza. Scholars generally agree that Paggi had little stylistic impact on Castiglione, but as his studio became a place of collaboration among many different artists, it exposed Castiglione to a wide array of personalities and styles. Just as Castiglione became fascinated by Rembrandt’s etchings, Scorza too found inspiration in the work of Northern artists such as Jan Bruegel the Elder. The adaptation of Northern styles and popular Northern subject matter was a prominent, even defining trend in seicento Genoa, and Castiglione’s Oriental Heads are just one instance of this pervasive pattern. Although no other written record of Castiglione’s interest in Rembrandt’s work remains, the Oriental Heads and Castiglione’s drawings of heads stand as testimonies to this fascination with his Dutch contemporary. It is therefore possible that certain erudite Roman buyers of the prints in the late 1640s would have been aware of the Dutch tradition of tronies, if not directly of Rembrandt, and could have thus read Castiglione’s Heads as a subtle nod to the importance of Genoa as a locus of Dutch artistic collaboration. The etchings can now be read as emblems of Castiglione’s self-fashioned image while abroad in Rome.

Prints as a Self-Fashioned Image

In his seminal study, Stephen Greenblatt argued that in the early modern period there was a heightened awareness of “self-consciousness about the fashioning of the human identity as a manipulable, artful process.”[33] During his time abroad, Castiglione likely sought to pursue such a process in order to become well-known as a specific, individual artist. In Soprani’s biography of Castiglione, the artist is described as a skilled painter and as a volatile, difficult person. According to Soprani, “When [Castiglione] was not oppressed by his own wickedness, he was truly cheerful and merry, jestful.”[34] Additionally, Soprani describes Castiglione’s sense of fashion, asserting that he dressed in rich yet bizarre clothing.[35] Soprani’s description of Castiglione paints an image of a man driven by intense emotions, both good and bad, with a propensity for theatrical clothing. Soprani’s Vite speaks to the perception of Castiglione as a strange, idiosyncratic figure. Castiglione was just one of the countless artists in the early modern period with a reputation for eccentricity. Artists were often thought of as “eccentric,” which could mean angry, peculiar, fantastic, bizarre, capricious, whimsical, and even charming.[36] Eccentricity was part and parcel of the persona of the Renaissance and Baroque artist. Many viewed the quality among artists as desirable and even fashionable, and in the mid-sixteenth century, artists began to co-mingle with the social and intellectual elite.[37] By the time Castiglione appeared on the scene, his theatricality and idiosyncrasy was a key component of his identity as an artist, and his opulence and extravagance also conformed to fashionable expectations of the day.

Castiglione was certainly not the only artist who was distinctly aware of promoting a specific identity; Salvator Rosa was another artist working at the same time as Castiglione, who is often described as an eccentric. Rosa was also known for his affinity for theater and drama, and even publicly acted like an eccentric Neapolitan. He was known for parading through the streets of Rome, dressed as a Neapolitan nobleman as if to display himself as a wealthy, distinctly Neapolitan character to the Roman public.[38] Though Castiglione was not necessarily known for parading in a similar manner, his tendency to wear fine yet “bizarre” clothing can easily be seen as a method of what Mary Rogers calls “playacting.”[39] Both Rosa and Castiglione were foreigners working in Rome, who sought to establish themselves as more than artists; their idiosyncratic identities manifested themselves in their own lives as well as their art.

Castiglione’s presentation of his eccentric persona through printed imagery was an important component of the artist’s self-fashioned identity. Other artists working in Rome in the mid-seventeenth century created prints for a few important purposes; the first purpose was to sell the prints for fairly affordable prices, earning a small income from works on paper rather than relying exclusively on larger commissions. The second purpose was to advertise the virtuosity of the artist, thereby encouraging potential patrons to commission paintings. Some artists, such as Salvator Rosa, created etchings in the hopes that consumers would believe the print to be a copy of an earlier painting, and may then inquire about the original painting.[40] Furthermore, there is another striking parallel between Salvator Rosa’s mode of self-fashioning and Castiglione’s: the two artists both produced a series of bust portraits that resemble the tradition of Dutch tronies. Rosa painted his bust portraits at exactly the same time that Castiglione created the Oriental Heads (in the late 1640s) and gave these works as gifts to his friends in Florence.[41] Rosa’s teste di fantasia varied and included philosophers, Turks, soldiers, and bandits, all of which were types rooted in the seicento interest in exoticism. It follows that Castiglione would have utilized his skill in etching in a similar way.

As previously mentioned, Castiglione published some of his other larger etchings through the De Rossi family publishing company, one of the leading distributors in Rome at the time, and sold these works for a small sum. For example, one of his most well-known works, The Genius of Castiglione, sold for ten baiocchi, a fairly low price compared to other prints distributed by the De Rossi company at the time.[42] The lower price of these works was likely because Castiglione was less well-known in Rome than some of his contemporaries, like Poussin, whose prints sold for much higher prices.[43] Similar to Rosa’s prints, Castiglione’s etchings were not copies of his paintings and instead would have been used to advertise his virtuosity, in this case, to a primarily Roman audience. While little primary documentation exists on the Oriental Heads, one may easily imagine that these small works could have been sold inexpensively, both as a way for Castiglione to support himself monetarily and as an assertion of his artistic ingenuity to attract potential patrons.

Castiglione had earned a reputation as an eccentric, both due to his erratic personality and his fashion sense. To dramatize his image even further, he included a (likely) self-portrait in his Oriental Heads etchings, a classic mode of artistic self-fashioning. The Head of a man in shadow (fig. 14) bears striking similarities, as yet unnoted in the scholarship, to the image that most scholars accept as the self-portrait of the artist (fig. 15).[44] The similar type of headdress worn by both figures, the similarly shaped noses, and the equally aggressive eye contact seen in this image create strong parallels between the two images. While it is impossible to assert with full confidence that either (or both) of these etchings is truly a portrait of the artist, direct eye contact with the viewer was a common hallmark of self-portraits in the early modern period, making this a safe conclusion. The conflation between images and self-fashioning in the early modern period also speaks to the early modern tendency to conflate images with reality. This was especially true in the context of self-portraiture:

The terms that defined self-fashioning in the Renaissance theatre of life belonged to the same category as those that characterized the production of illusory art, and the emerging human persona was judged as fictional an entity as the emerging work of art. Successful illusion is the best characterization for both the human and the artistic product, whether the living person in actuality, or the persona who continued to live through the art.[45]

Figure 14. G. B. Castiglione, Head of a man in shadow turned slightly to the left, from the Large Oriental Heads series, ca. 1645-1650, etching. Sheet: 7 5/16 × 5 7/8 in. (18.6 × 15 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 15. G. B. Castiglione, Head of a man wearing a feathered cap, ca. 1645-1650, etching. 7 5/16 × 5 5/16 in. (18.5 × 13.5 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

If one understands early modern self-fashioning as illusory in the context of self-portraiture, Castiglione’s images then blurred the distinction between the playful and the serious, and between the image and reality itself.

In fact, some scholars have sought to demonstrate that this blurry distinction allowed artists to toy with ideas presented in their artwork. The strength of the connection between images, such as Castiglione’s depictions of exotic foreigners and reality itself, was crucial for Rupert Shepherd, who argued the following:

… there was a much greater tendency to conflate a depiction with the thing it depicted than there is nowadays. This conflation could, on occasion be so extreme as to lead to the viewer (mis)taking the image for the thing it depicted. The viewer might even … treat the image as if it were itself alive, as if it really were the thing it depicted.[46]

This is not to suggest that the buyer of the Oriental Heads etchings truly thought the figures were alive, or even that the prints had any sort of trompe l’oiel effect. Rather, Castiglione’s prints can be effectively understood as cogent, strategic instances of his promotion of his association with the Ottoman East on the basis of his Genoese identity, alongside his predilection for dressing in foreign costume in his own life.

While his nickname, Il Grechetto, which roughly translates to the friendly “the Greek guy,” has often been associated with one of his many modes of foreign dress, Castiglione never signed his work with his nickname. As such, it is unlikely that he personally sought to portray himself as specifically Greek. Instead, he was known for sporadically dressing as an Armenian, among his many other costumes.[47] To return to his presumed self-portrait, which, while not technically printed within his series of Oriental Heads, follows a similar format, Castiglione wears a floppy cap with a feather, not unlike the headdresses that appear throughout some of his etchings. Though it was more or less typical for a European artist at the time, the drama associated with the large feather and his intense, even hostile facial expression recalls his reputation as recorded by Soprani.

Conclusion: Towards a Genoese Artistic Identity

While more research is required to discover any literary responses to Castiglione’s Oriental Heads, their prominence around Italy can be attested to by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo’s work over a century later. Around 1770, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo produced a series of etchings of turbaned men, similar stylistically in quality of line and composition to Castiglione’s, with one striking exception: Tiepolo’s figures face away from the viewer, making the turban the focal point of the work (fig. 16, fig. 17). By turning the sitters in such a way that their faces become invisible, the artist leaves the headdress as the only distinct identifying element in the etchings, effectively becoming the very identity of the figures. Tiepolo’s print might then be understood as a possible response to Castiglione’s heads, as both series rely upon the symbolic associations with vaguely “Oriental” headdresses as depicted in bust portraits.

Figure 16. Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Bearded man wearing a turban, depicted in bust length from behind in three-quarters view, from the Raccolta di teste series, ca. 1770, etching. Sheet: 7 1/2 x 4 13/16 in. (19 x 12.3 cm), plate: 4 13/16 x 3 9/16 in. (12.3 x 9.1 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure 16. Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Bearded man wearing a turban, depicted in bust length from behind in three-quarters view, from the Raccolta di teste series, ca. 1770, etching. Sheet: 7 1/2 x 4 13/16 in. (19 x 12.3 cm), plate: 4 13/16 x 3 9/16 in. (12.3 x 9.1 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Castiglione’s Oriental Heads etchings are nearly ubiquitous in major museum collections today, supporting the notion that they were sold on the Roman art market, an important center of print collecting and distribution in the early modern period. By fusing his artistic, technical virtuosity with the association between Genoa and Ottoman costume vis-a-vis Oriental costume, Castiglione invoked a titillating and fearsome image of the Ottoman Turk. Castiglione was a savvy businessman, who sought to promote his work on the basis of his cosmopolitanism. While depictions of turbaned Ottoman Turks remained popular in the oeuvres of multiple artists, including Stefano della Bella and G. D. Tiepolo, Castiglione’s stand out as a moment in which the complex images of the art world of Genoa in seicento Rome begin to visibly emerge.

[1] On the Roman print market, see Rose Marie San Juan, Rome: A City out of Print (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001); Francesca Consagra, The De Rossi Family Print Publishing Shop: a Study in the History of the Print Industry in Seventeenth-Century Rome, PhD Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, 1994.

[2] For a biography of Castiglione and an overview of his oeuvre, see Timothy Standring and Martin Clayton’s Castiglione: Lost Genius (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013); Anthony Blunt, The Drawings of G.B. Castiglione & Stefano della Bella in the collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle (London: Phaidon Press, 1954); Paolo Bellini, L’opera incise di Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (Milan Ripartizione Cultura e Spettacolo, 1982); Ann Percy and Anthony Blunt, Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione: Master Draughtsman of the Italian Baroque (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1971).

[3] The etchings are technically divided into two series: the ‘large’ oriental heads and the ‘small’ oriental heads. For the purposes of this paper, I shall treat the two series as one coherent issue, though when distinctions are necessary, the prints will be distinguished based on their size.

[4] Anthony Blunt. The Drawings of G.B. Castiglione & Stefano della Bella in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle (London: Phaidon Press, 1954), 6.

[5] Timothy J. Standring, and Martin Clayton, Castiglione: Lost Genius (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013), 81.

[6] Bellini, “Italian Master of the Seventeenth Century,” In The Illustrated Bartsch, 48.

[7] Ibid.

[8] On the archival sources on the De Rossi publishing company, see Consagra, 1994.

[9] Blunt, 6.

[10] See also Creighton Gilbert “A preface to signatures (with some cases in Venice)” in Fashioning Identities in Renaissance Art, ed. Mary Rogers (Brookfield: Ashgate, 2000), 79. Gilbert also raises a more broad question of whether artists’ signatures in Renaissance works are specific to commissions out of his or her own city of residence. As Gilbert explains, this question is nearly impossible to answer yet, and one can only speculate. Even so, this possibility is especially compelling to consider in the case of Castiglione’s signatures, which specify his identity as “Genovese.”

[11] Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans. S.G.C. Middlemore (New York: Oxford University Press, 1937), 146.

[12] Ayesha Ramachandran, The Worldmakers: Global Imagining in Early Modern Europe (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2015).

[13] Ulrike Ilg, “Stefano della Bella and Melchior Lorck: the Practical Use of an Artist’s Model Book,” Master Drawings 41 No. 1 (2003): 30-43.

[14] On the political relationship between the Papacy and the Ottomans, see Kenneth M. Setton, The Papacy and the Levant, 4 vols. (Philadelphia, 1974).

[15] See Heather Madar’s “Dürer’s depictions of the Ottoman Turks: A case of early modern Orientalism?” in The Turk and Islam in the Western Eye, ed. James G. Harper (Burlington: Ashgate, 2011), 155-183, which discusses Ottoman costume in the work of Dürer’s apocalyptic scenes.

[16] See Madar; For more historical views of the Ottomans in early modern Europe see John Bohnstedt, “The Infidel Scourge of God: the Turkish Menace as seen by German Pamphleteers of the Reformation Era,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 58/9 (1968): 1-58; Anna Contadini, ed. The Renaissance and the Ottoman world (Ashgate, 2013); Michael Frassetto, and David R. Blanks, eds. Western Views of Islam in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (New York, 1999); Timothy Hampton, “Turkish Dogs”: Rabelais, Erasmus and the Rhetoric of Alterity,” Representations 0.41 (1993); Noel Malcolm, Useful Enemies: Islam and the Ottoman Empire in Western Political Thought, 1450-1750 (Oxford: OUP, 2019); Margaret Meserve, Empires of Islam in Renaissance Historical Thought (Cambridge, MA: HUP, 2008); Schwoebel, Robert. The Shadow of the Crescent: the Renaissance Image of the Turk 1453-1517 (Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1967); Angelo Tamborra, Angelo, Gli stati Italiani de l’Europa e il problema Turco dopo Lepanto (Florence, 1961); Christine Woodhead, “The Present Terrour of the world?’ Contemporary views of the Ottoman Empire, c. 1600” History 72 (1987): 20-37.

[17] Hampton 1993; Woodhead 1987.

[18] Roland Barthes, The Language of Fashion, trans. Andy Stafford (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013), 4.