![]()

![]()

The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Artist Bruce Conner is perhaps best known as an early West Coast maker of assemblage. Of the innumerable assemblages Conner created between 1958 and 1964, nearly all of them contain nylon stockings as a central material. While Conner’s use of nylon in his assemblage works has been well documented—the material is so ubiquitous as to be impossible to ignore—the literature has failed to account for the history of nylon itself and the way this history informed Conner’s use of the material.

An early discovery of the petrochemical industry, which would come to dominate and define American consumer life, nylon was closely tied to World War II in both its early manufacturing and marketing. From its inception in the early 1930’s, nylon was viewed as an important competitor with the Japanese silk industry. This took on greater significance with the outbreak of the Second World War, during which all nylon production was diverted to war-related manufacturing. Nylon was and remained, however, a material for women’s stockings, and it was marketed in this way throughout the war despite widespread shortages of nylon hosiery. The shortages caused dramatic consumer dissatisfaction and constant media coverage. In other words, nylon was more than a material or a commodity—it was a sustained subject within the American imagination at midcentury.

Applying an interdisciplinary combination of textile history and art history, this paper uses the history of nylon’s discovery, manufacture, and marketing as a frame for understanding Bruce Conner’s consistent use of the material in his sculpture. The paper first establishes the close relationship between nylon and World War II, then suggests several instances in which Conner alludes to that history both verbally and in the work itself. The paper uses the history of nylon and its close connection to war-related manufacturing to expand on prior scholarship that has aligned Conner’s use of the material with sex and violence. Additionally, it offers a possible link between Conner’s assemblages and other works from his oeuvre that more explicitly engage the history and legacy of World War II and its connections to Cold War politics.

![]()

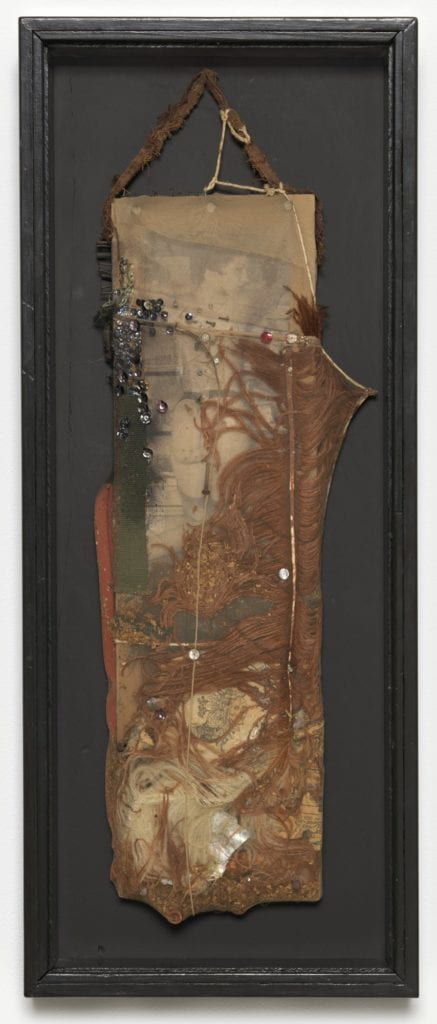

An oblong assemblage hangs from a strap of frayed burlap. It measures nearly two and a half feet long and over ten inches wide. Rusted nails puncture the periphery of the upper left-hand corner, leading the eye to a smattering of silver and purple sequins. Beneath this pierced and embellished exterior, several layers of nylon stockings obscure and reveal a black-and-white photograph of a woman. Her back faces us, her head turned to the right in profile. Her body is bare apart from a black garter belt and matching hosiery. Nails cut through her nylon shield, impaling and violating her body. Below and beside her image, feathers, fabric, shells, string, red rubber tubing, and loose tobacco threaten to break through the nylon encasement. A razor blade hovers menacingly in the mass. An image of a skull peaks through the feathers, a symbol of death. The work is Bruce Conner’s BLACK DAHLIA (Fig. 1). Named for one of the most infamous American murders to occur in the years immediately following World War II, the assemblage evinces Conner’s use of nylon as a veiling layer, a psychosexual motif, and an allusion to the ties between postwar commodities and militarized violence.

Just four year after making BLACK DAHLIA, Conner abandoned assemblage. A creative chameleon with an aversion to being pinned down, the artist left assemblage behind partially in response to his increasingly common definition by critics as the “nylon-stocking artist.”[i] Indeed, nylon stockings are a unifying material across almost all of the innumerable assemblages the artist made between 1958 and 1964. Yet, despite the specificity and ubiquity of the textile in Conner’s work from the period, few historians have dedicated more than a few paragraphs to his use of it. This is curious considering the fiber’s omnipresence, the entanglement of its invention and early marketing with the Second World War, and its continued media prominence in the postwar period. Nylon was more than a material. It was a phenomenon; one whose manufacture and media presence were deeply entrenched in the war effort. Given Conner’s well-documented antiwar stance, and his artistic engagement with World War II through other means and media, it is somewhat surprising that the literature has failed to examine the artist’s use of nylon in relation to its history. This paper will do precisely that, first sketching the history of the textile’s emergence and mass media coverage, and then addressing evidence for Conner’s awareness of this history and its appearance in particular assemblages.

Fig. 1 Bruce Conner, BLACK DAHLIA, 1960, photomechanical reproductions, feather, fabrics, rubber tubing, razor blade, nails, tobacco, sequins, string, shell, and paint encased in nylon stocking over wood, 26 3/4 x 10 3/4 x 2 ¾ in. (67.9 x 27.3 x 7 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Before we can account for Conner’s use of nylon, it is necessary to outline the material’s invention as both a fiber and a commodity. Nylon was discovered through a series of experiments conducted by the DuPont Company between 1928 and 1930.[ii] Almost immediately, as Susan Smulyan notes, DuPont directed the new material toward the manufacture of stockings, rather than “toothbrushes or synthetic wool or any number of other possibilities” the fiber presented.[iii] This decision had nationalist overtones: nylon offered an American alternative to Japanese-imported silk, and as a result, was positioned by the company and the press not only as silk’s new rival, “but as an anti-Japanese commodity.”[iv] Beginning with its first public appearance at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, nylon made headlines as a “Major Blow to Japan’s Silk Trade.”[v] This characterization gained even greater significance once World War II began.

In 1941, a year after nylons became available to the public, the United States placed an embargo on silk, seized all existing supplies from private manufacturers, and diverted them to wartime production.[vi] Six months later, all nylon was similarly redirected toward the manufacture of parachutes, munitions containers, and other military requirements.[vii] But first, to symbolize the United States’ economic independence from Japan, an American flag was woven in nylon and raised at the White House.[viii]

While nylon proved a boon to the United States war effort, its redirection resulted in widespread shortages of stockings throughout the country. In response, DuPont, along with help from the government and the press, promoted nylon’s strength, emphasized its importance to the war, and commended women’s contribution.[ix] This appeal to patriotic sacrifice caught on. As Susannah Handley chronicles, “Newspapers reported stories of girls ‘Sending Their Nylons off to War,’ carried photographs of leggy women taking their stockings off ‘for Uncle Sam,’ and described how it would take 4,000 pairs to make bomber tires.”[x] Amid this performance of patriotism, the demand for nylons persisted, and a black market emerged on which they were sold for as much as ten or twelve dollars per pair.[xi]

Even after the war’s end, DuPont repeatedly failed to satisfy the appetite for nylon stockings, resulting in widespread “nylon riots.”[xii] These so-called “riots,” in which women waited in line for many hours to buy a few pairs of stockings, made newspaper headlines for months beginning in September 1945.[xiii] The press coverage portrayed women as hysterical, violent, and unruly.[xiv] It also continued to linguistically link nylon to war with titles like, “Women Risk Life and Limb in Bitter Battle for Nylons,” and “Nylon Sale and No Casualties.”[xv] Thus, from its earliest inception through the postwar period, nylon and its market were intimately intertwined with the Second World War. And this connection was broadcast on a national scale. As Handley argues, “The scarcity of nylon stockings had turned them into symbols of luxury, and the passion with which they were pursued could almost be likened to the Beatlemania of the next generation.”[xvi] In other words, nylons were more than a commodity. They were a media-fueled sensation.

By the 1950s, nylon had come to symbolize “a new way of life, the future, the spirit of America and its mythical modernity.”[xvii] As the first fully synthetic fiber, nylon exemplified the new American normal, in which conspicuous consumption was made easier by cheaply manufactured chemical materials. It also served as a crucial precursor to many of the plastics that became ubiquitous in the fifties and sixties, which were critical to developments in Pop and Minimalism.[xviii] But unlike the Pop artists, who immortalized this unprecedented consumption with slick renderings of freshly-bought items—Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans come to mind—Conner used nylon to reveal the dark underbelly and broken promises of America’s new consumer culture.

Although Conner never explicitly referenced the above history, there are several instances where his comments indicate a coded consciousness of the craze for nylon and its association with war. One such instance occurs in the artist’s discussion of BLACK DAHLIA. Conner asserted that one of the themes of the work was, “the characteristics of femininity, which many times men turn into weapons…to attack the woman.”[xix] He continued, “Women wear all this armor that is incontrovertibly transformed into weapons against them.”[xx] This can be read as a general commentary on the sexism of American society, which simultaneously sexualizes women and then blames them for it. However, Conner’s language is a bit more specific. He is interested particularly in the garments and accessories women wear to perform their femininity, which he defines as “armor” that men convert “into weapons.” As apparel meant to confer modesty on the wearer, which is nonetheless eroticized, nylon stockings exemplify this conflict. Yet nylons were also literally transformed into weapons. As we have seen, DuPont originally developed nylon as a material for hose, but during World War II it was diverted to make tank tires, containers for explosives, and other wartime necessities. During the war, this diversion was used to advertise nylon’s strength with the promise that pantyhose would be available once the conflict concluded. When the war ended and manufacturers failed to meet the consumer demand this advertising had stoked, the consumer herself was chastised for her purportedly unreasonable expectations.[xxi] During these years of scarcity, women who went to buy nylons were caricatured in the media as crazed, frivolous fools.[xxii] Thus, a garment worn to protect women from accusations of immodesty was “transformed into [a] weapon against them.” Though this extrapolation may seem a stretch, that Conner would refer specifically to the worn characteristics of femininity in relation to BLACK DAHLIA is strange and significant. For in the violent crime to which the work’s title refers, Elizabeth Short’s body was discovered naked and mutilated, brutally stripped of its gendered attire.[xxiii]

Another instance in which Conner alludes to the militarized and gendered history of nylon comes from a 1963 student publication issued in conjunction with the University of Chicago art festival. In it, Conner published a joke plea, stating:

I am turning to nylon stocking assembling and would appreciate small dignified announcement in school paper that I have a nylon stocking fetish and place a dignified receptacle for contribution at the exhibit of my work. It is very difficult to obtain them by legal sources. … I will also hope (but not request openly) to get brassieres, panties, dirty photos, jewelry, feathers, psyloceben [sic], smoke writers in the sky, lamp posts.[xxiv]

This passage is crucial for several reasons. First, it indicates that Conner actively sought out the nylons he used, rather than finding them in secondhand shops or among the detritus of San Francisco’s Western Addition neighborhood, where he sourced most of the materials in his assemblages. This demonstrates that nylons held a singular importance for the artist that necessitated hunting them down rather than finding them organically. Conner’s solicitation for donations also mirrors the news reports that lauded women for donating their stockings to the war effort.

Second, on the surface Conner’s statement passes as a self-deprecating jab that apologizes for his use of hosiery, which during the early sixties would have been considered indecent. However, Conner is employing two definitions of “fetish” at once. In the first case, the term refers to an object of sexual fixation—usually a clothing item or body part—whose imagined or real presence is necessary for an individual to reach climax. Freud argued that fetishism compensates for the fear of castration, which arises when a little boy discovers that his mother lacks a penis. To assimilate this traumatic realization, the boy develops the fetish, which serves as a “substitute” for the mother’s missing phallus.[xxv] In the Freudian interpretation, then, the eroticism of the fetish is entangled with the threat of violence, an implication that maps onto the news reports suggesting that the demand for nylons amounted to a risk of “life and limb.” Beneath these sexual overtones, Conner’s statement also employs the understanding of the fetish as, “an object of irrational reverence or obsessive devotion,” to use the Merriam-Webster definition. In this way, Conner covertly references the consumerist furor that led to the so-called “nylon riots,” which turned stockings into an object of such profound desire that the frenzy at their sales frequently made headlines. This reading is confirmed by what Conner says next: “It is very difficult to obtain them by legal sources.” This refers to the black market for nylons that emerged during World War II. Yet, the temporal distance between the war and 1963, when Conner published this passage, allowed this sly reference to read instead as an insinuation that Conner had to resort to theft to satisfy his “fetish”. Conner therefore concealed his secondary meaning through sexual innuendo, which was reinforced by the materials he lists “but [does] not request openly.”

The polysemic, cryptic language Conner uses in each of these examples fits comfortably within the artist’s career-long resistance to easy definition, both in terms of his art and his artistic identity. As Laura Hoptman and others have identified, Conner engaged in “a lifelong struggle against being defined by technique, tendency, medium, or…reception.”[xxvi] Assemblage was only the first of several artistic media that the artist adopted and then abandoned; among the others were painting and photography. Conner was also deeply ambivalent about what he disparagingly referred to as “the art bizness,” which encompassed not only the art market, but also the institutional network of museums, image circulation, and press that kept the market afloat.[xxvii] A persistent prankster who was distrustful of language over vision, it follows that Conner would describe his assemblages in such oblique terms.[xxviii]

Just as he resisted easy categorization as an artist, he also encouraged complex and evolving understandings of his work. In 2005, Conner said of his assemblages, “I chose not to put the work into a box or a frame where it couldn’t be changed. I expected it to change. I never considered it to be ‘finished’. I put a date on it when I put it up on the wall, but that was all the date meant to me.”[xxix] This indicates that Conner hoped for physical interventions in his work and welcomed the possibility that the content might change as well. He was staunchly resistant to the idea that there exists one concrete truth, a point he made clear in an interview with Peter Boswell in 1986: “A rewarding experience for me is a narrative structure where you are not told what to think and what to do. Otherwise, that’s what you get in jail. That’s what you get with government. And when you get it in art, it can put you to sleep.”[xxx] It is clear, then, that he would not have entered anything into the public record that he felt was too specific or prescriptive. After all, one of the strengths of his assemblages is their visual complexity, which breeds multivalent meanings.

With that in mind, I do not intend to argue that Conner’s use of nylon is always in reference to the history outlined above. He used it in many ways across hundreds of artworks. Nonetheless, it offers a compelling and heretofore unexamined means for better understanding one aspect of his assemblages. Specifically, the history of nylon and its close connection to war-related manufacturing might bolster and expand prior scholarship that has more impressionistically aligned Conner’s use of the material with sex and violence. Additionally, it offers a link between Conner’s nylon-shrouded assemblages and other works he made throughout his life that more explicitly engage the history and legacy of World War II, and its connections to Cold War politics.

For instance, in 1959 and 1960, Conner made several works with military references in their titles, all of which contain stretched, wadded, or running nylon: RAT WAR UNIFORM, RAT SECRET WEAPON, MEDICAL CORPS FOR RAT WAR, RAT USO, RAT HAND GRENADE (all 1959), and GENERIC RAT HAND GRENADE (1960).[xxxi] The “rat” in all of these is a reference to Conner’s Rat Bastard Protective Association, a coalition of artists that he loosely assembled into a club sometime around 1957–58 (the exact date is unknown).[xxxii] The group’s name derived from the Scavenger’s Protective Association—San Francisco’s garbage collectors—with whom Conner felt an affinity due to their shared collection of detritus.[xxxiii] The artist once likened his use of nylon to the burlap bags that hung from the garbage collectors’ trucks as they hauled the trash away. [xxxiv] “Rat Bastard” came from an insult that Conner’s friend and fellow member Michael McClure heard while working at a local gym.[xxxv] In its appropriation of a slur, the name indicated a shared sense of alienation on the part of the members.[xxxvi]

John Bowles first suggested, and Anastasia Aukeman supports, the idea that these militant Rat Bastard-related titles indicated Conner’s desire to create “an army of Rat Bastards.”[xxxvii] This is an oddly straightforward reading, which neglects the fact that Conner was vehemently and vocally antimilitary. As Conner himself said, throughout the late fifties, he was anxiously aware that he was draft age.[xxxviii] He viewed the draft as “the worst violation [he] could imagine,” and moved to San Francisco from his hometown of Wichita, Kansas, in part because he felt it offered better odds of gaining military exemption.[xxxix] Thus, to assume that Conner’s use of war-related language in his titles indicated that the artist was harboring a hope of martial insurrection seems off the mark. Instead, it seems possible that through these titles, Conner was referring to the nylon in these early assemblages. In particular, RAT WAR UNIFORM might be understood as linguistically combining nylon’s status as garment and wartime aid, while RAT SECRET WEAPON could refer to the profound importance nylon played in military manufacturing.

This reading is reinforced when understood in relation to other assemblages Conner made the same year. Rachel Federman suggests that beginning in 1959, Conner made several works incorporating black wax that expressed “his profound disillusionment with U.S. foreign and domestic policy during the Cold War, and with the nuclear arms race in particular.”[xl] Numerous nylon works from the same year suggest a similar, though veiled critique.

Specifically, Conner created a suite of spider-themed works that are worth exploring in more depth: SPIDER LADY, SPIDER LADY NEST, SPIDER LADY HOUSE, SPIDER LADY DUNGEON, and ARACHNE (all 1959). Aukeman proposes that these works explore “hidden or repressed sexual fantasies.”[xli] However, given their distinctly abstract rendering and lack of sexual imagery in comparison with Conner’s other assemblages, there is room for a more nuanced assessment.

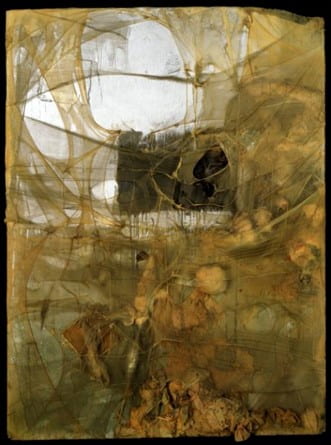

ARACHNE (Fig. 2), for instance, is a large-scale assemblage measuring approximately five feet high by four feet wide, with a depth of four inches. The work is shrouded in nylon cobwebs, the stockings pulled taut to the point of breaking, creating stiff arabesques that run over the surface of the work. Beneath this top screen of ripping and running nylon, still more nylon is wadded up, knotted, and balled. The accumulation of sheer layers simultaneously holds the work together and hides it from view, concealing a doll’s head, beads, and bits of newsprint trapped like insects beneath. The effect is one of bodily, bandaged accumulation, intestinal tubes and nodules of nylon suspended on the work’s painted collage support. In the top center of the composition, a cavernous abyss is rendered in dripping black paint, obscured by overlapping lines of nylon and wire.

Fig. 2 Bruce Conner, ARACHNE, 1959, mixed media: nylon stockings, collage, cardboard, 65 3/4 x 48 3/4 x 4 1/4 in. (167.0 x 123.8 x 10.7 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

As Aukeman points out, the title of the work refers to the Greek myth of Arachne, a mortal weaver of such tremendous skill that she enraged the goddess Athena, who retaliated by ripping Arachne’s tapestry from her loom and turning her into a spider.[xlii] Aukeman ponders whether Conner identified with Arachne or Athena,[xliii] but I would suggest that the artist invoked the myth as myth, rather than psychologically aligning himself with one of its protagonists. The spider woman offers ambiguous symbolism as a skilled weaver, a maternal protectress, and an entrapping temptress. As we have seen, seduction and the threat of corporal harm are interwoven within fetishism, and Conner was quick to acknowledge the fetishistic quality of nylon stockings. This characteristic is visually expressed through bulbous nylon appendages that cover the surface of ARACHNE, conjuring Freud’s assertion that the fetish is a substitute for the mother’s missing phallus. The artist visualizes the menace of castration and death Arachne poses as both mother and seductress through splatters of red pigment that lend the masses of nylon a bloody bandage-like effect. But Arachne is also a woman imprisoned within a spider’s body, making her both the trapper and the trapped. In this way, she exemplifies Conner’s assertion that feminine accessories like nylon stockings captured women within a contradictory expectation of allure and modesty, an objectifying force that fed postwar consumerism and gendered violence alike.

Kevin Hatch argues that ARACHNE annihilates the subjecthood of the viewer: “its nylon strands veil nothing but its own voided core,” offering “no place for the observer whatsoever, no escape, no refuge.”[xliv] As a dangerous, seductive woman, we might say that Arachne is the agent of this obliteration, luring innocents to her web. Yet this threat of destruction and death has another layer of meaning within the context of the myth. The tale of Arachne is a cautionary one, a warning that humans should not claim the power of gods, lest they be punished for their hubris. In Conner’s formulation, the stretched, wrapped, and ripped nylon in the work is Arachne’s web, which was once a beautiful tapestry, but due to the arrogance of its weaver has become abject and ruined, breeding only darkness and decimation. In this respect, the work might be understood in relation to Conner’s lifelong fascination and abhorrence toward the nuclear bomb and the arms race of the Cold War, which represented such an unprecedented and devastating assertion of dominion over nature and human life as to be almost biblical in proportion. As a child, Conner watched documentation of the July 25, 1946, submarine bomb test conducted at Bikini Atoll.[xlv] The footage left a profound impression on the artist and remained an object of fascination and fear that Conner repeatedly used in his work. Most notably, it appears in his 1976 film CROSSROADS, “which consists entirely of declassified government footage of the underwater Bikini test explosion.”[xlvi]

Beyond its marketing and manufacturing associations with World War II, nylon has an eerie connection to the development of the atomic bomb. DuPont, the same petrochemical company that invented the textile, was a major player in the Manhattan Project, developing the plutonium that was a key ingredient in the bomb dropped on Nagasaki.[xlvii] Whether Conner was aware of this connection is hard to know. If he was, he never stated it outright in the myriad interviews he gave throughout his career. Nevertheless, it confirms a thematic thread that ran through the heart of so much of his oeuvre: the simultaneous seduction and repulsion he felt in response to atomic warfare.

At the very least, Conner’s use of nylon might be interpreted as a nod to the fragility of life during the Cold War era, when the possibility of an impending nuclear attack never felt far away. Describing the first time he took the hallucinogenic drug peyote, Conner said,

I experienced myself as this very tenuously held-together construction—the tendons and muscles and organs loosely hanging around inside—and it seemed like at any moment disaster could strike and you could fall apart…. you were just held together by this thin skin and strings of flesh. And shortly after that I started working on a number of named pieces, but the first one was Snore, which has all these organ-like lumps of things.[xlviii]

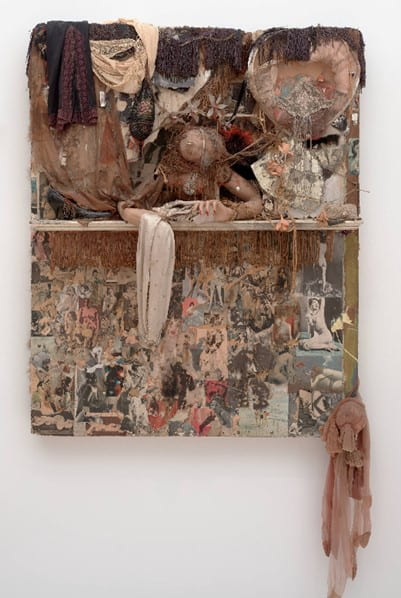

SNORE (Fig. 3) is composed almost entirely of nylon; its delicate fibers bunched into pendulous blobs that are held inside stretched layers of stringy nylon skin. In this way, SNORE isolates another crucial aspect the Conner’s use of nylon that so many scholars have hedged toward but never stated. In its closeness to the body, its fleshy tones, and its elasticity, nylon acts as a kind of second skin, albeit one that is far from universal in its limited range of pale hues. Nonetheless, Conner exploited this quality in many of his assemblages, lending them a corporal presence. Conner often emphasized the gendered nature of this surrogate skin by incorporating costume jewelry and other feminine “masks,” as he called them.[xlix] But without these, the effect is simply bodily, allowing Conner to create works like SNORE. The assemblage’s title is at once comic and foreboding, for the body is most vulnerable in sleep. Towards the top of the work, a metal can with a black mouth gapes at the viewer. Conner’s title implies slumber, but the abstracted figure could just as easily be screaming.

Fig. 3 Bruce Conner, SNORE, 1960, wood, nylon, and metal, 36 1/2 x 17 1/2 x 21 1/2 in. (92.7 x 44.5 x 54.6 cm), Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

The corporeality Conner could conjure with nylon was apparent to him from the very first work he defined as an assemblage, RATBASTARD (Fig. 4). The artist described the piece as a “wounded” painting covered with nylon stockings, affixed with “a picture of a cadaver on an operating table…with wire and wood representing bones and structure.”[l] For Conner, the work took on its own “persona.”[li] In this description, the wounded painting and the injured body become one and the same, as the work’s various bodily features—nylon skin, wood bones—combine to create a figure. However, the specter of American violence and militarism was always present too, as evinced in RATBASTARD’s slashed canvas and corpse, as well as nails and bloody brown paint stains that appear around the periphery of the work (Fig. 5).

Figs. 4 & 5 Bruce Conner, RATBASTARD, (recto and verso), 1958, wood, canvas, nylon, newspaper, photographic reproduction, wire, oil paint, nails, bead chain, etc., 16-1/2 x 9-1/4 x 2-3/4 inches, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN.

The alignment of nylon with United States military manufacturing, and the visual parallel Conner drew between the material and violence provide a potential answer to a question that has not yet been posed in the literature. Namely, why Conner almost entirely stopped using nylon when he moved to Mexico City with his wife Jean in 1961. Of the many assemblages Conner made while the couple was living there between 1961 and 1962, only a few incorporate the material at all. Of course, this was partially due to the difference in available tools, and the couple’s lack of a social network in Mexico. Conner found that the people of Mexico did not discard their belongings as readily as Americans, making the refuse he was accustomed to using scarcer.[lii] Additionally, their short-term stay likely prevented the artist from sourcing nylons from friends or acquaintances.

Nonetheless, there was also a thematic reason for Conner’s shift in materials. In a letter to Museum of Modern Art curator William Seitz, Conner wrote of his time in Mexico, “It is difficult for me to understand USA violence here…I feel I have left most all the oppressive scene behind me.”[liii] Given the myriad connections between “USA violence” and Conner’s use of nylon outlined above, this statement is a compelling argument for the artist’s sudden stop in its use. This reading is bolstered by the fact that shortly after the artist returned to the United States in 1963, he submitted his coded request for nylon donations at the University of Chicago.

One year later, in 1964, Conner ceased making assemblages altogether. This was partially due to the increasing institutionalization and popularity the form had gained in the preceding years. William Seitz, the same curator Conner wrote to from Mexico, had organized the landmark exhibition The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961. The show gave a name, historical lineage, and establishment approval to a style that only a few years earlier had seemed marginal. For Conner, the increasing attention being paid to assemblage and the resultant notice his own work was generating threatened stale convention. As Peter Boswell discerned, Conner “resented the pressure to continue in the same mold. But…he [was also] tired of the static nature of what had become, in just a few years, ‘conventional assemblage making.’”[liv] Aukeman notes that one of the reasons Conner was initially attracted to assemblage was that it lacked a name or style, and as such, was free from tradition or established norms.[lv] Once recognition and labeling took hold, Conner jettisoned the form that had brought him fame for fear of being pigeonholed.

But Conner also grew tired of the object-ness of his assemblages. He began to see in them, “an unnecessary gross attachment to property and objects,” in which he was “entrapped” due to his need to preserve and store them.[lvi] Work that was once outside and critical of the capitalist system due to its discarded materiality began to feel corrupted by commerce. “I see a continuing campaign,” Conner said, “on the part of controllers of art to turn these things into commodities, to define what individuals are doing with their hands so that they conform to a political, social, and economic agenda that pertains to the establishment, finance, and the art world.”[lvii] Conner refused to participate in that process, and so, famously, he “stopped gluing big chunks of the world in place.”[lviii]

Conner’s final assemblage, LOOKING GLASS (Fig. 6), can be understood as a virulent critique of American consumer culture, the commodification of femininity, and in turn, the commodification of women themselves. A confrontational final opus measuring five by four feet, the work reaches out toward the viewer with mannequin arms, conjuring a fortuneteller figure. Her head is not a woman’s but a blowfish, its spikes poking through layers of suffocating nylon, its lips gasping for breath. She emerges from layers of feminine accouterment: nylons, lingerie, fringe, feathers, fake flowers, costume jewelry, a high-heeled shoe, and a beaded purse. Conner once called accessories of this sort “demonic devices” that do not represent women, but instead constitute objects of martyrdom akin to “the chains and the locks and the crowns of thorns.”[lix] And indeed, the figure in LOOKING GLASS is bound to them with rope that wraps around her wrist and cuts across her throat.

Fig. 6 Bruce Conner, LOOKING GLASS, 1964, mixed media on Masonite, 60 1/2 x 48 x 14 1/2 in. (153.67 x 121.92 x 36.83 cm), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA.

Below the ledge on which she rests, the bottom half of the work is covered in ripped and stapled pornography. Hundreds of nude women populate this portion of the piece, revealing an subterranean world where objects of desire are no longer the commodities above, but women themselves. In the lower right corner, a cascading conglomeration of nylons connects the two spheres of the work, making clear that they are one and the same. As an object of both sexual and consumer fetishism, nylon stockings eliminate the difference between them, revealing American consumption as the burden borne and worn by women. In keeping with Conner’s earlier work, there is an inherent violence to this wearing and bearing, exemplified by the layers of nylon that seem to strangle and blind the blowfish face above. In this way, nylon becomes a metonym for the entanglement of consumerism with gendered subjugation and state brutality. Shards of broken mirror and the work’s title make clear that this is not Conner’s personal psychosexual fantasy, but a reflection of us all. LOOKING GLASS is the barbarism of American consumerism and sexism staring you in the face. For though the blowfish is blinded, just above it, a woman’s eyes peer out beneath layers of fringe and flowers.

Knowledge of nylon’s early history is crucial to the analysis above. Without it, LOOKING GLASS reads as an overblown fetish itself, its accumulation of sexual imagery and objects serving merely to reinforce their venereal charge. With it, the work becomes a broader meditation on the ills of American production and consumption, whether of objects, images, or ideology. Nylon, through its manufacture and marketing, was key to the production of all three. As such, it was a complex material that Conner mined in myriad ways.

Its erotic and gendered associations could be mobilized to great effect, but this was far from the only meaning Conner unraveled from the fiber. Its interwoven history with World War II in its production and publicity, as well as its resultant status as an overvalued luxury good, proved equally fruitful for the artist. Resolutely antiwar, Conner used nylon to create concealed allegories relating to the ruin of human invention by military conflict, and the fragility of human life in the age of nuclear weapons. Nylon’s corporal qualities allowed Conner to create pseudo figures with the fiber, conjuring polyp-like protrusions, entrails, and skin-like encasings. He also never lost sight of the material’s status as both a sexual and consumer fetish.

Nylon was perhaps the quintessential American commodity at midcentury. It represented the country’s nationalist economic agenda, served as a crucial weapon during the Second World War, and was critical to the chemical engineering developments that engendered rampant postwar consumerism. In all of these ways, it provided the perfect material means for Conner to question American consumption, Cold War politics, patriarchal gender constructions, and violence writ large. However, nylon’s greatest potential lay in its flimsy and flexible materiality, for unlike a Campbell’s soup can or a Brillo box, which cannot escape their concrete commodity status, nylon stockings are more surface than object. As such, they allowed Conner to achieve the kind of narrative multiplicity and ambiguity for which he strove in all his artwork.

[i] Peter Boswell, “Bruce Conner: The Theater of Light and Shadow,” in 2000 BC: the Bruce Conner story Part II, ed. Peter Boswell, Bruce Jenkins, and Joan Rothfuss (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1999), 44.

[ii] Susan Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon: The Struggle Over Gender and Consumption,” in Popular Ideologies, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 41.

[iii] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 47–8.

[iv] Smulyan, 44; Susannah Handley, “‘N’ Day: The Dawn of Nylon,” in Nylon: The Story of a Fashion Revolution: a celebration of design from art silk to nylon and thinking fibres, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 35.

[v] “$10,000,000 Plant to Make Synthetic Yarn: Major Blow to Japan’s Silk Trade Seen,” New York Times, Oct. 21, 1938.

[vi] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 55.

[vii] Smulyan, 55.

[viii] Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 48.

[ix] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 56.

[x] Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 48.

[xi] Handley, 48.

[xii] Handley, 50; Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 58.

[xiii] Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 50.

[xiv] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 61–2.

[xv] Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 50.

[xvi] Handley, 50.

[xvii] Pap Ndiaye, Nylon and Bombs: DuPont and the March of Modern America, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 2.

[xviii] Ndiaye, Nylon and Bombs, 2; Handley, “‘N’ Day,” 40.

[xix] Bruce Conner and John Yau, “Folded Mirror: Excerpts of an Interview with Bruce Conner,” On Paper 2, no. 5 (May–June 1998), 34.

[xx] Conner and Yau, “Folded Mirror,” 34.

[xxi] Smulyan, “The Magic of Nylon,” 61–62.

[xxii] Smulyan, 70.

[xxiii] Greil Marcus, “Bruce Conner’s Black Dahlia,” in Bruce Conner: It’s All True, ed. Rudolf Frieling and Gary Garrels (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 79.

[xxiv] Bruce Conner quoted in Rebecca Solnit, Secret Exhibition: Six California Artists of the Cold War Period, (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1990), 63.

[xxv] Sigmund Freud, “Fetishism,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 21, trans. and ed. James Strachey, et al, (London: Hogarth Press, 1961), 152–157.

[xxvi] Laura Hoptman, “Beyond Compare: Bruce Conner’s Assemblage Moment, 1958-64,” in It’s All True, ed. Rudolf Frieling and Gary Garrels (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 283.

[xxvii] Hoptman, “Beyond Compare,” 282.

[xxviii] Greil Marcus, “Bruce Conner: The Gnostic Strain,” Artforum 31, no. 4 (Dec. 1992), 75.

[xxix] Hans Ulrich Obrist and Gunnar B. Kvaran, “Interview: Bruce Conner.” Domus, no. 885 (Oct. 2005), 23.

[xxx] Bruce Conner in discussion with Peter Boswell, February 11, 1986, quoted in Boswell, “Bruce Conner: The Theater,” 31.

[xxxi] Anastasia Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland: Bruce Conner and the Rat Bastard Protective Association, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016), 138. I cite this list because it seems that these works are no longer extant except in their printed descriptions.

[xxxii] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 138.

[xxxiii] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 71; Kevin Hatch, “‘It has to do with the theater’: Bruce Conner’s Ratbastards,” October 127, (Winter 2009), 117.

[xxxiv] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 138.

[xxxv] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 61.

[xxxvi] Hatch, “It has to do,” 117.

[xxxvii] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 138.

[xxxviii] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 64.

[xxxix] Bruce Conner quoted in Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 64; Rachel Federman, “Bruce Conner: fifty years in show business,” in Bruce Conner: It’s All True, ed. Rudolf Frieling and Gary Garrels (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 29.

[xl] Federman, “Bruce Conner,” 83.

[xli] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 138.

[xlii] Aukeman, 142.

[xliii] Aukeman, 142.

[xliv] Hatch, “It has to do,” 132.

[xlv] Federman, “Bruce Conner,” 83.

[xlvi] Federman, 83.

[xlvii] Ndiaye, Nylon and Bombs, 2 and 143.

[xlviii] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 62–3.

[xlix] Solnit, 65.

[l] Marc Selwyn, “Marilyn and the spaghetti theory,” Flash Art 24, no. 154 (Jan.–Feb. 1991), 94.

[li] Selwyn, “Marilyn and the spaghetti theory,” 94.

[lii] Federman, “Bruce Conner,” 86.

[liii] Letter from Bruce Conner to William Seitz, undated (probably Dec 1961) BCP quoted in Federman, “Bruce Conner,” 86.

[liv] Boswell, “Bruce Conner: The Theater,” 44.

[lv] Aukeman, Welcome to Painterland, 188.

[lvi] Selwyn, “Marilyn and the spaghetti theory,” 94.

[lvii] Selwyn, 97.

[lviii] Obrist and Kvaran, “Interview: Bruce Conner,” 23.

[lix] Solnit, Secret Exhibition, 65.

Charlotte Kinberger is a master’s candidate at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, focusing on modern and contemporary art. Her research interests include revisionist histories of Modernism, “Craft” and “Folk” art, textile and costume history, and feminist and critical race theory. She studied Art History and Material Culture at Sarah Lawrence College and the University of Oxford and has held internship positions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. More recently, she has served as the Gallery Manager at James Fuentes, New York, and the Assistant Director at Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco.

The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

The Description de l’Égypte is an encyclopedia of the findings of Napoleon’s army in Egypt during their 1798–1801 invasion and occupation. In this paper, I compare the original drawings produced in Egypt with the final prints and the ancient monuments. After careful consideration of the artist materials used to create the Description, this study reveals instances in which the savants and the engravers exerted creative agency over the content, composition, and style of the printed images. I argue that these examples highlight the imperial narrative of the work and its Orientalist underpinnings while also serving to discredit French claims of objectivity in representation.

![]()

The Description de l’Égypte, ou, Receuil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’armée française is a 24-volume encyclopedia that details the scientific findings of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) and his army during the 1798-1801 French invasion, occupation, and exploration of Egypt. The Commission des Sciences et des Arts d’Égypte accompanied the army with the mission of documenting and disseminating information relevant to Napoleon’s political and military campaigns. The Commission, known collectively as the savants, consisted of 150 engineers, artists, scientists, and architects. During the occupation, the savants produced detailed notes, sketches, and maps of Egyptian monuments which would form the intellectual basis of the Description de l’Égypte.

In 1801, when Napoleon’s generals capitulated to Admiral Nelson and abandoned Egypt, the British took possession of the antiquities gathered by the French, most notably the Rosetta Stone. However, the French were permitted to keep their notes, sketches, and other papers. In 1802, Napoleon declared that the findings of his army would be published at the government’s expense as a massive, multi-volume illustrated book. The Description de l’Égypte is divided into three sections: antiquities, natural history, and the modern state. The complete set consists of nine volumes of text, fourteen volumes of prints, and the Explication des planches – a text directory to the plates. Although 1,000 engravings were proposed, only 837 engravings were produced in total. The French government sub-contracted the production of the plates to five printmakers in Paris.[i] The ten volumes of explanatory text were published by the Imprimerie Impériale (later the Imprimerie Nationale). The first volume was available to subscribers in 1809 and the final volume was published in 1829.

The Description de l’Égypte, considered to be the first major text in Egyptology, is believed to have influenced the trajectory of the discipline even before the translation of the hieroglyphs by Jean-François Champollion in 1822. However, historians David Prochaska and Anne Godlewska argue that the Description de l’Égypte reveals more about its French authors than it does about Egypt. Prochaska reads the plates as examples of cultural orientalism in both the political and intellectual realm.[ii] He concludes that the knowledge-gathering activities of the savants actively supported Napoleon’s military and imperial ambitions. Godlewska examines the maps of the Description and identifies the goals of the cartography within the ideology of empire.[iii] She notes how the French believed that the monuments of ancient Egypt were a testament to singular strength of the pharaoh, a leadership model Napoleon sought to emulate. She observes that the French chose to record elements that highlight civic strength, yet ignored those that show ruin, neglect, and vestiges of Mamluk rule in Egypt.

In the Preface to the Description, Joseph Fourier, a mathematician and the first editor of the Description, poetically links conceptions of empirical truth with the art of engraving. Godlewska writes that for Fourier: “truth was largely assumed to be synonymous with science…[Fourier] makes it clear that the mission of the text is scientific representation. If something could be represented with precision, detail, or accuracy it clearly had the value of truth. The ultimate in truth was reproducibility.”[iv]

Fourier’s position is grounded in the Enlightenment notion that truth could be conveyed by representation and images. The engravings of the Description, based on the drawings produced in Egypt by the savants, led them to claim scientific objectivity.

While the Description de l’Égypte is a masterpiece because of its scale, the technical supremacy of its engravings, and its overall beauty as a work of art, it cannot be read as an objective representation of Egypt during the French invasion. I suggest the artistic techniques used to translate stone monument to print reveal the culturally constructed biases of its authors. The choices made by the savants and the engravers were motivated by the imperial narrative predominant in Napoleon-era France. These examples demonstrate how the engravers actively contributed to the content and composition of the prints. As a result, any study of the Description is incomplete without acknowledging the interventions and hidden intentions of the authors.

In this paper I consult the preliminary drawings sketched by the savants in Egypt. Of the 816 drawings held and digitized by the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), this article examines 10 drawings and their related prints. The study is limited to just three sites – Philae, Medinet Habu, and Karnak. Philae, the first site presented in the Description, is notable for scholars as an early document of its pre-flood condition. The site suffered from frequent flooding since the construction of the Aswan Low Dam in 1902. The Philae temple complex was dismantled and relocated to a neighboring island prior to the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1970. Medinet Habu and Karnak were selected because the sites have been well-documented by archeologists. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago recorded and published the reliefs at Medinet Habu and Karnak as part of their epigraphic survey of Egyptian monuments.

Several institutions have digitized their sets of the Description de l’Égypte. In this paper, I consult the high-resolution tiff images of the prints from the New York Public Library. The original drawings are held in the BnF and are available to view online. Although I have viewed several volumes of the Description de l’Égypte in person at The Explorer’s Club in New York City, in this article my primary method of studying the prints and drawings was by viewing the digital downloads in Adobe Photoshop using the zoom tool for magnification. As a result, I cannot comment on the effects of the various papers used for the prints and drawings, nor can I make any claims about the scale of the drawings in comparison to the printed images. However, the digital nature of my investigation has allowed a sustained examination of the drawings and prints under intense magnification and a direct side-by-side comparison that would not have been otherwise possible in the reading room.

As prints are not objective, I suggest that engraving should be understood as a fundamentally interpretive medium. The technical process of engraving reduces drawings to patterns of lines and dots. These lines suggest shape, shading, value, and color. A substantial amount of translation was required by both the savant and engraver to represent three-dimensional stone carvings on a two-dimensional sheet of paper. Therefore, it is useful to begin this discussion by examining the various media used to create the images within the Description.

Many of the drawings produced by the savants in Egypt were made with crayon noir. In contemporary French, crayon translates to pencil. However, in the late eighteenth-century, crayon denoted the invention of Nicolas-Jacques Conté (1755–1805), the scientist and inventor best known for inventing fabricated graphite, called the conte crayon. He was also an early member of Napoleon’s scientific commission in Egypt. Previously, graphite had been manufactured by the English, by using mined plumbago to create a drawing medium. In contrast, Conté combined clay, powdered graphite, and lampblack to produce graphite rods. He was issued a patent for his invention in 1795 and manufactured the rods in several levels of hardness and blackness.[v] Conte crayons were quickly adopted by artists, writers, and those engaged in technical drawing.[vi] Conte crayons were preferred by technicians because they were manufactured to be consistent and permanent. English pencils made with mined leads could be erased from paper with breadcrumbs whereas the conte crayon could not. In this way, in the words of Richard Taws, “…Conté’s pencils stopped time. Their marks were indelible, as permanent as an engraving.”[vii]

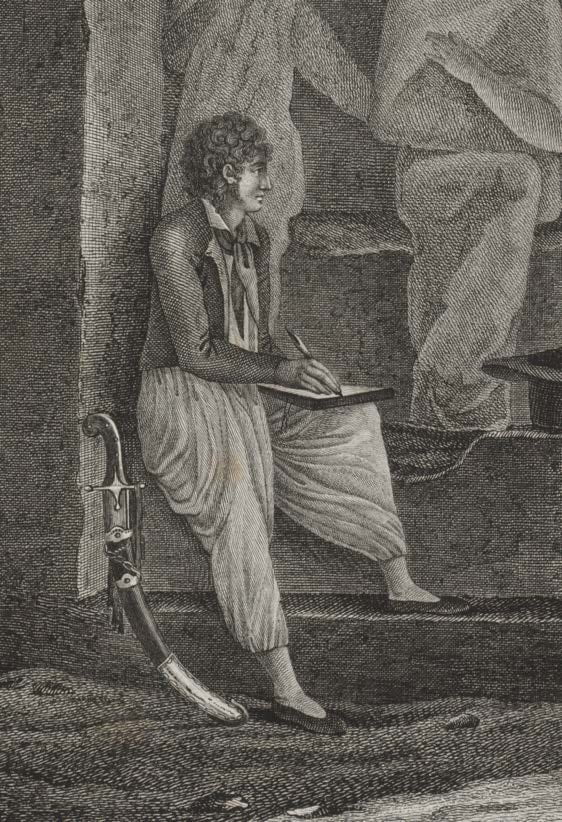

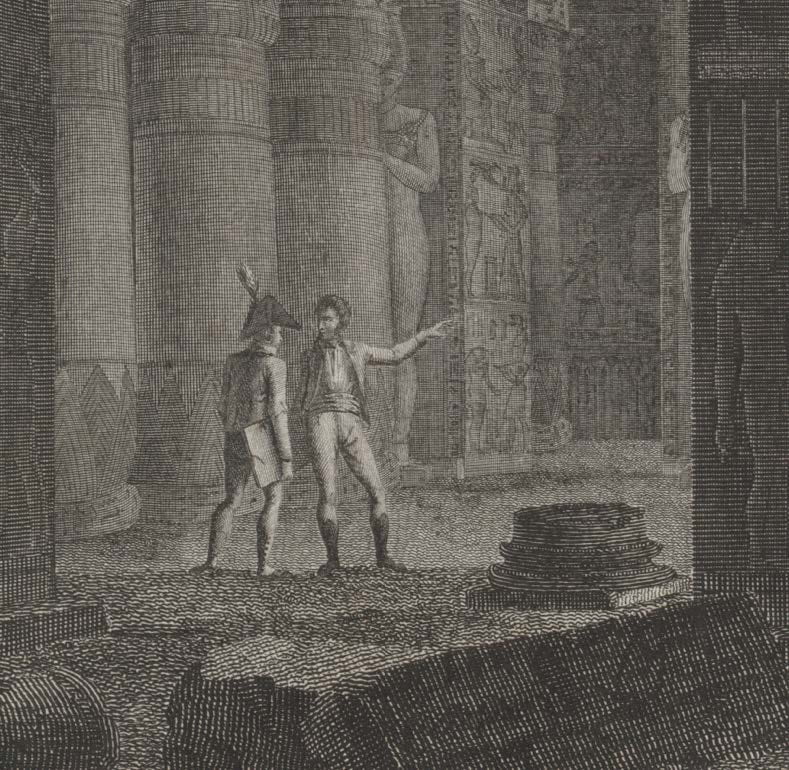

Some of the prints in the Description show the savants at work recording the monuments. The savants are depicted facing the monument with their drawing board, often wearing a top hat and coat. This type of human staffage was frequently used in architectural drawings to provide both scale and context to the monuments. For example, in plate 67 (Fig. 1) there is a savant sketching the temple of El-Kab holding a double ended porte-crayon in his hand. In the eighteenth-century, graphite rods were not encased in wood (the form of the modern-day pencil). Rather, the rods were held in a device called a porte-crayon. The claw grips at either end of the device held an un-encased piece of crayon. These vises were made from wood and later metal.[viii]

Fig. 1 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 67. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Gilbert-Joseph-Gaspard de Chabrol de Volvic (1773–1843), a civil engineer, used crayon almost exclusively for his drawings. Chabrol, a graduate of the École polytechnique and a member of Napoleon’s team, designed bridges and roads to transport military equipment and personnel.[ix] Chabrol would have been trained in the principles of descriptive geometry at the École polytechnique. Descriptive geometry was developed in the eighteenth-century by Gaspard Monge, a founder of the École polytechnique. Descriptive geometry claims to be equal part art and science, applying mathematical rigor to the practice of drawing.[x] This method for rendering three-dimensions in only two was adopted by architects, surveyors, and engineers to record objects and buildings on paper with detail and precision. In this manner, descriptive geometry was deemed the most truthful method of representation because the “…association with measurement mathematics and observational instrumentation … lent [the images] apparent objectivity.”[xi]

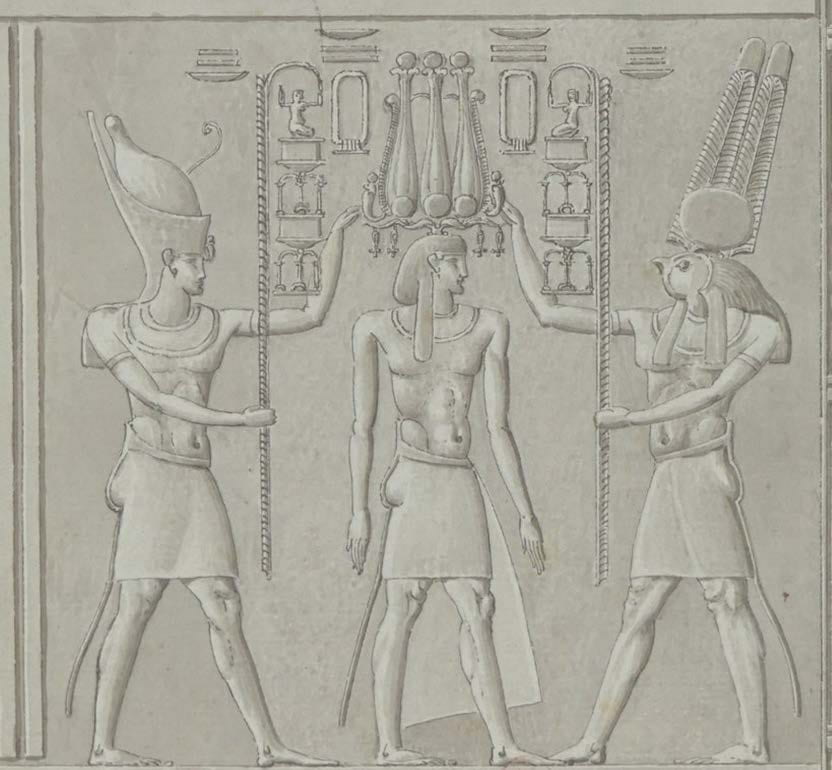

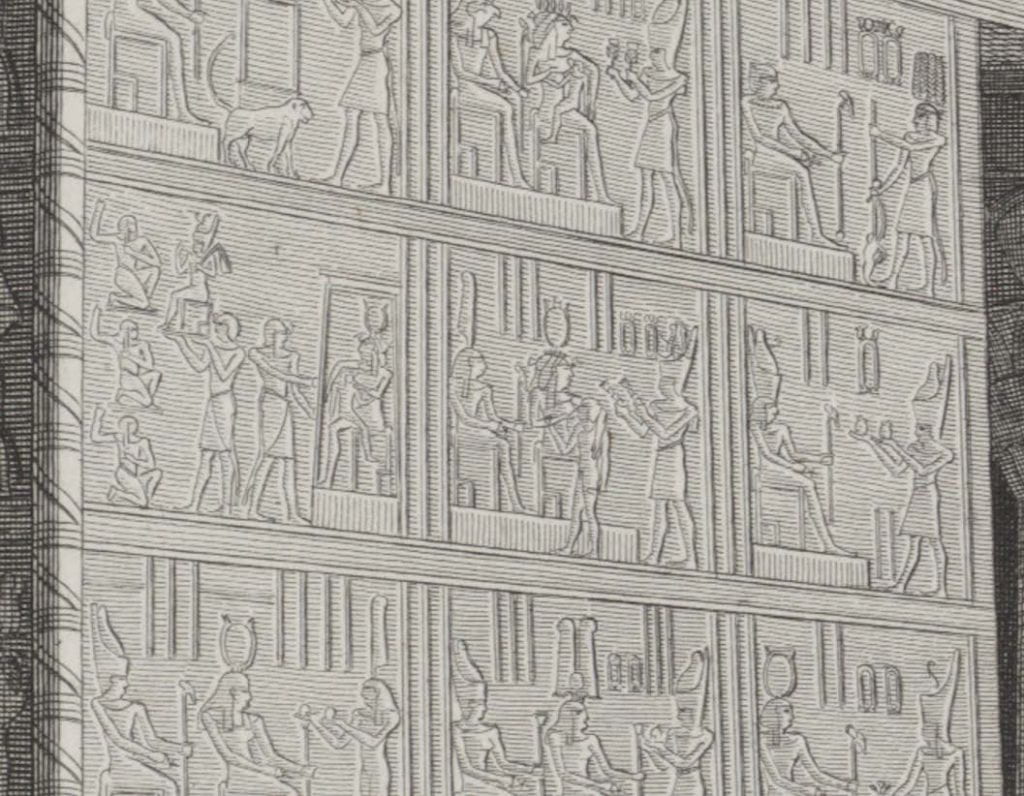

Chabrol’s training in descriptive geometry is apparent when examining one of several sketches of wall relief from Philae (Fig. 2). His system for creating tonal effects is schematic and simple; it communicates depth with flat layers of highlight, mid-tone, and shadow. Chabrol used the side of a pencil to create an overall mid-tone, almost like a ground, on the paper. Highlights were subtracted by erasing the mid-tone and shadows were rendered by additional shading in pencil. Chabrol does not include additional shading to define the musculature of the figures. This drawing is reproduced in Plate 22 of Volume I of the Description, along with other small reliefs sketched by Chabrol (Fig. 3). The engraving was meant to be understood as a perfect reproduction of the drawing, which in turn was a perfect reproduction of the carving. In the early modern period, engraving was considered a mimetic method of reproduction. Engraving was understood by some as a reproductive technology, rather than an artistic medium. Indeed, the Printmaking Bible states, “…the stylized nature of the prints reduced the art of engraving to one of reproduction rather than that of a medium capable of creative or original design.”[xii] The engraver is not an artist, but rather a craftsman or artisan. Image quality is measured by technical excellence.[xiii] Additionally, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, engraving was sometimes regarded as merely mechanical and uninventive.

![Fig. 2 Chabrol de Volvic, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs du temple de l'ouest], 1798-1809, crayon noir et plume, 27.8 x 44.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-2-1024x694.jpg)

Fig. 2 Chabrol de Volvic, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs du temple de l’ouest], 1798-1809, crayon noir et plume, 27.8 x 44.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 3 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 22. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

For example, the engraving of Chabrol’s drawing reproduces the tonal effects of the conte crayon in two ways. The figures are rendered with stipple engraving. To create this effect, the engraver would use a burin to gouge out a pattern of dots to create passages of tone. By increasing the density of dots, the engraver could suggest an increase in value. Parallel lines imitate the flat wall. Stipple and line are used together, even though Chabrol’s shaded mid-tone does not graphically differentiate a change in the surface of the stone carving.

In the engraving, the wall may have been rendered exclusively in lines because it created less work for the engraver. Conté developed an engraving machine that could render perfectly straight lines that were spaced at regular distances. His machine reduced the work of eight months to just two or three days.[xv] This technique was especially effective for depicting the vast cloudless Egyptian sky. Richard Taws writes that “the uncannily serene visual effect [the engravers] created, generated a strangeness all their own.”[xvi] The regular lines appeared highly mechanical to Western viewers. The perfectly straight lines of the wall suggest a perfectly smooth, flat stone surface. However, in reality, the sandstone surfaces of Philae were damaged from frequent flooding. Ultimately, the overall effect of the parallel lines is one that separates the wall relief from its context as part of an ancient monument.

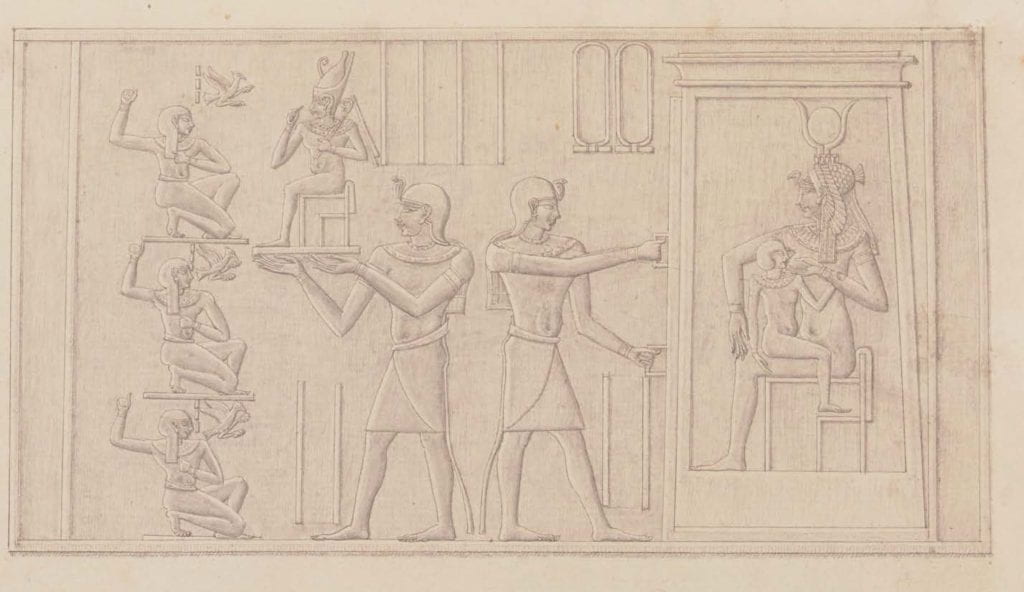

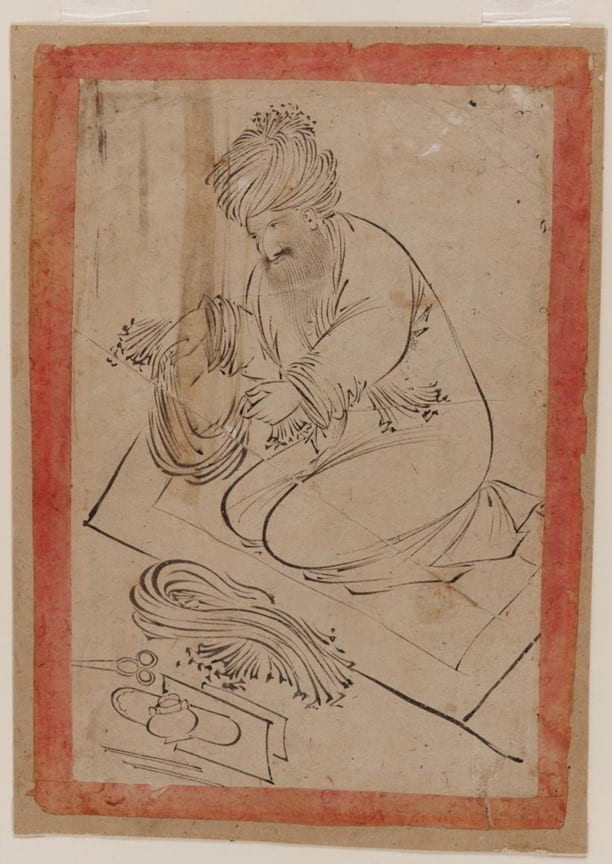

Other savants received their artistic training outside of the École polytechnique, such as Charles Louis Balzac (1752–1820), an architect and artist. As a painter, Balzac exhibited at salons during the French Revolution.[xvii] Balzac primarily used lavis d’encre, or ink wash, for his drawings. In contrast to crayon, which is a dry medium, ink is a wet medium. Ink is a fluid suspension of fine particles in water and a binding medium. Inks are generally applied with a nibbed pen but can be thinned with water and applied with a brush, known as wash. Balzac also used aquarelle, or watercolor. Watercolor is a paint medium of pigment powder, water, and a gum binder. It is applied as transparent washes with soft sable brushes. As a result of using wet media in his works, Balzac’s style is distinctly more painterly than that of Chabrol, as seen in his relief from Philae (Fig. 4). Although Balzac used the same general principles of highlight, mid-tone, and shadow as Chabrol, Balzac applied darker washes to accentuate subtleties of the stone surface and the musculature of the figure. The final engraving (Fig. 5) uses the same convention of stipple for the figures and line for the walls as seen above. Where Balzac has rendered shadow, the stippling is denser. In this manner, the engravings neither imitate the drawing media nor differentiate wet or dry application.

Fig. 4 Charles-Louis Balzac, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-relief du Grand temple], 1798-1809, aquarelle,

lavis d’encre et plume, 15.6 x 20.1 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 5 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 12. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

One of the most obvious changes between Balzac’s drawings and the final engravings concerns facial details. Unlike Chabrol who meticulously rendered the faces in sharp pencil, Balzac used ink and wash to casually suggest features. The eyes are reduced to lines; nostrils and lips are omitted. Yet, the final engravings include facial details not depicted in Balzac’s original sketches. The faces are styled to resemble those drawn by Chabrol. As seen previously, Chabrol paid particular attention to the finest of details, especially in the faces and headgear. His high level of detail was retained almost exactly in the engravings.

In another sketch by Balzac of Philae (Fig. 6), small figures are rendered with thick brushed lines and as such, the facial features are vague. Wash is used to render the shadow of eye sockets and the area under the cheekbone. However, as above, the engravers extrapolated from the sketches and included simple facial details, such as rounded noses and smiles with upward turned lips (Fig. 7). Very little of Balzac’s shading technique of the figures is retained in the engravings. Unlike the previous reliefs, the engravers used parallel lines to render both figure and wall.

![Fig. 6 Charles-Louis Balzac, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs de l'édifice de l'ouest], 1798-1809, aquarelle, lavis d'encre et plume, 21.4 x 27.1 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-6-1024x678.jpg)

Fig. 6 Charles-Louis Balzac, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs de l’édifice de l’ouest], 1798-1809, aquarelle, lavis d’encre et plume, 21.4 x 27.1 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 7 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 19. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York

Public Library, New York, NY.

More than 400 printmakers were employed over the course of the twenty-year production of the work. At the bottom of each print, the author of the drawing is acknowledged as well as an engraver. However, each print produced for the Description was the result of many hands, with each member of the printshop contributing a particular skill or area of expertise. There was a need to maintain consistency in all the images, especially considering that five different print shops were tasked with producing the plates. The regularizing of the features was likely part of a conscious effort to create a unified style that could be replicated over the course of many years and many volumes.

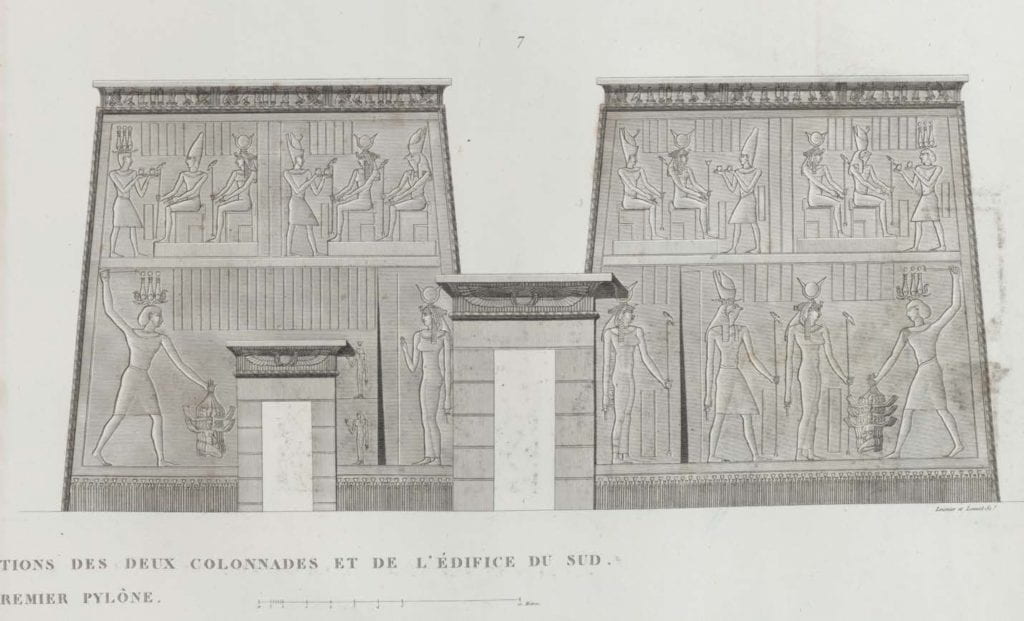

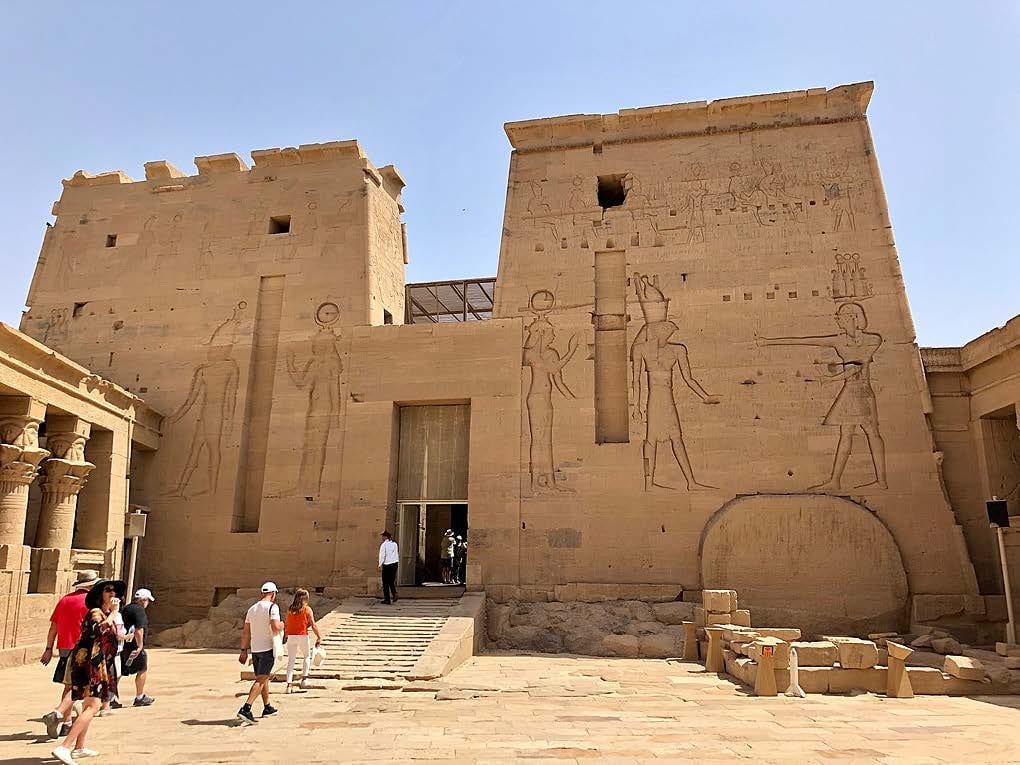

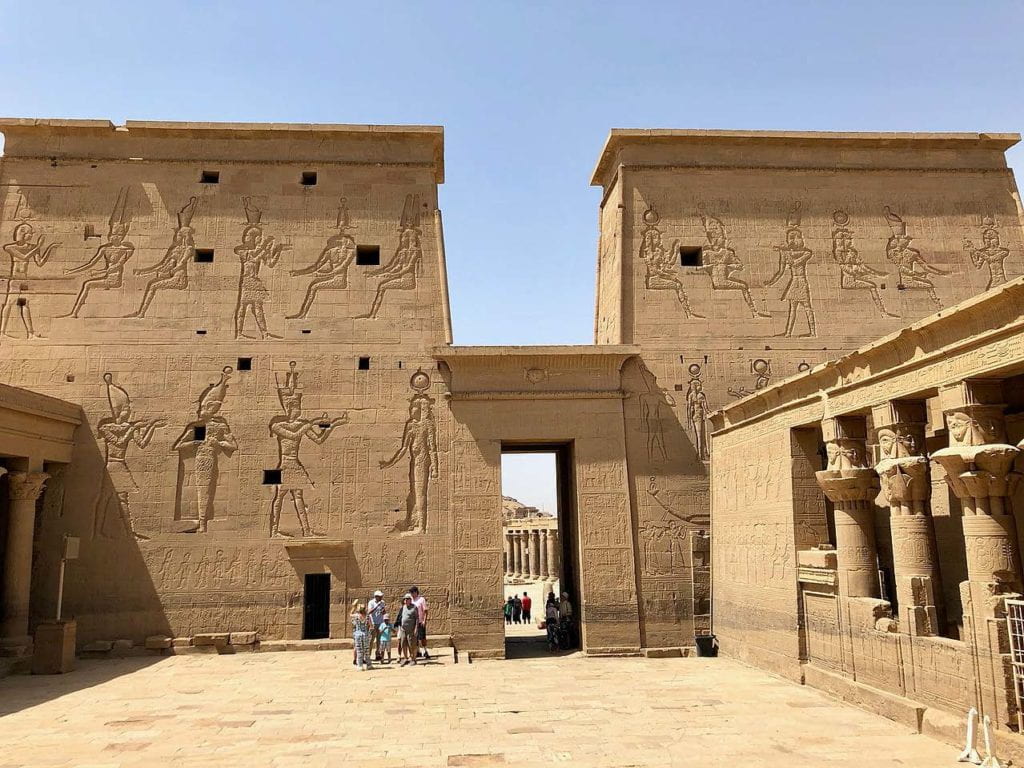

Descriptive geometry was designed to render Western architectural styles. As a result, it is limited in its ability to express Eastern styles and features. Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois (1776–1842) and Édouard de Villiers du Terrage (1780–1855), both civil engineers at the École polytechnique, produced this measured drawing of the first pylon of the Isle of Philae (Fig. 8). At first glance, both the preliminary drawing and the engraving (Fig. 9) suggest that the wall carvings are rendered bas-relief. A controlled combination of stipple, line, and shading were employed to show the dimensional differences of the wall surface. However, this photograph (Fig. 10) reveals that the carvings on the pylon are, in fact, sunk relief rather than bas-relief. With sunk relief carving, the wall surface is left flat and the area around the forms is removed. The forms within the carved area are rendered in low relief, the highest point of which never goes beyond the plane of the wall surface. Sunk relief creates strong shadows around the figures depending on the time of day and angle of the viewer, as seen in the photograph. The style is mostly limited to Egyptian art, so the Western system of descriptive geometry lacked graphic conventions for adequately expressing the peculiarities of sunk relief. This salient feature of Egyptian sculpture was, in a sense, lost in translation.

![Fig. 8 Jollois et de Villiers, [Ile de Philae] : [dessin], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre et crayon. No dimensions provided. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-8.jpg)

Fig. 8 Jollois et de Villiers, [Ile de Philae] : [dessin], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre et crayon. No dimensions provided. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 9 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 6. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Fig. 10 Ryckaert, Marc, Aswan (Egypt): Philae Temple – first pylon, 2012, digital photograph. Wikimedia Commons. <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Philae_Temple_R02.jpg>

Jollois and de Villiers misrepresented the first pylon in their drawing in more consequential ways. Most notably, the photograph shows a smaller structure, known as the Gate of Ptolemy II, that blocks the full view of the relief. Several figures’ gestures have been altered. For example, the two servants on the left side of the pylon are carved with open, flat palms. However, in the drawing, these same figures have their fists closed around small bottles. In the engraving, the servants have open palms, but are carrying the small bottles. On the right side of the pylon, one of the servants has crossed arms. In both the drawing and the engraving, the figures’ arms are uncrossed. These examples are minor instances of a phenomenon that is quite common throughout the Description de l’Égypte; the savants were not always diligent about transcribing exactly what they saw.

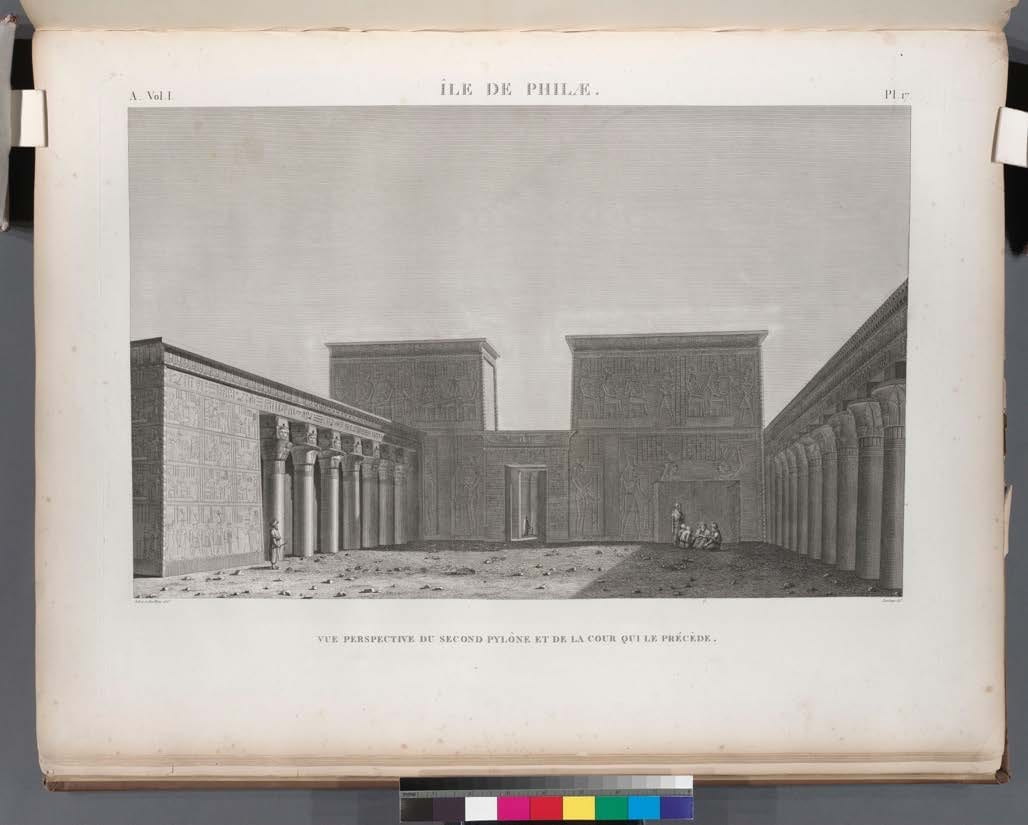

Plate 17 (Fig. 11) and its corresponding drawing (Fig. 12) depicting the second pylon at Philae differs from the monument (Fig. 13) so substantially, one must question if this drawing was produced in the presence of the monument or instead from a less-than-perfect memory. The figures in the upper frieze are substantially smaller on the monument than as depicted in the drawing, although the gestures and dress are accurate. The entryway of the drawing has an ornamental lintel which is not a feature of the actual monument. These alterations only make sense after examining the backside of the first pylon (Fig. 14). The proportion of the figures in the upper frieze and the entryway more closely resemble the first pylon than the second. One could speculate that this drawing is a patchwork of several different sketches made at Philae that were combined inaccurately to create a complete view of the pylon for publication.

Fig. 11 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 17. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

![Fig. 12 Jollois et de Villiers, [Ile de Philae] : [vue perspective du second pilône et de la cour], 1798- 1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 25.5 x 45 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-12.jpg)

Fig. 12 Jollois et de Villiers, [Ile de Philae] : [vue perspective du second pilône et de la cour], 1798- 1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 25.5 x 45 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 13 LeMay, Warren, Temple of Isis, Philae Temple Complex, Agilkia Island, Aswan, AG, EGY, 2019, digital photograph. Wikimedia Commons. <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_of_Isis,_Philae_Temple_Complex,_Agilkia_Island,_Aswan,_AG,_EGY_(48027128182).jpg>

Fig. 14 LeMay, Warren, Temple of Isis, Philae Temple Complex, Agilkia Island, Aswan, AG, EGY, 2019, digital photograph. Wikimedia Commons. <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_of_Isis,_Philae_Temple_Complex,_Agilkia_Island,_Aswan,_AG,_EGY_(48026992296).jpg>

Generally, the sketch and the engraving are in line with one another. The architectural features, columns, and capitals are captured by the print in detail. The sky consists of perfectly straight, parallel lines — a product of Conté’s engraving machine. Where Jollois and de Villiers use watercolor wash for tone and value, the engravers use crosshatched perpendicular lines. However, Plate 17 from Philae deviates from the original sketch in two ways that clearly demonstrate the influence of the engraver on the content of the final image. The print depicts relief around the central portico that is not included in the drawing. There is also an additional wall relief on the left side of the image that is not depicted in the sketch, nor on the monument. The engravers likely added these reliefs to fill empty space and to increase the size of the printed image so that it filled the whole page. Figure 15, a detail of Plate 17, shows this relief on the wall extension supplied by the engravers. The engraver recycled this image from a sketch from Philae made by Chabrol (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 17. Vol. I, 1809, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Fig. 16 Chabrol de Volvic, [Ile de Philae] : [bas-reliefs du temple de l’ouest], 1798-1809, crayon noir et plume. 27.8 x 44.2 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Linda Nochlin in her essay “The Imaginary Orient” discusses the use of authenticating details by Orientalist artists. Nochlin states that “the major function of gratuitous, accurate details … is to announce ‘we are the real.’ They are signifiers of the category of the real, there to give credibility to the ‘realness’ of the work as a whole, to authenticate the total visual field as a simple, artless reflection.”[xx] I suggest that much like how the Orientalist painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema included objects from the Egyptian galleries of the British Museum in his paintings, the engravers of the Description included reliefs from elsewhere in the work to add “realness” to what is in reality pure creation.

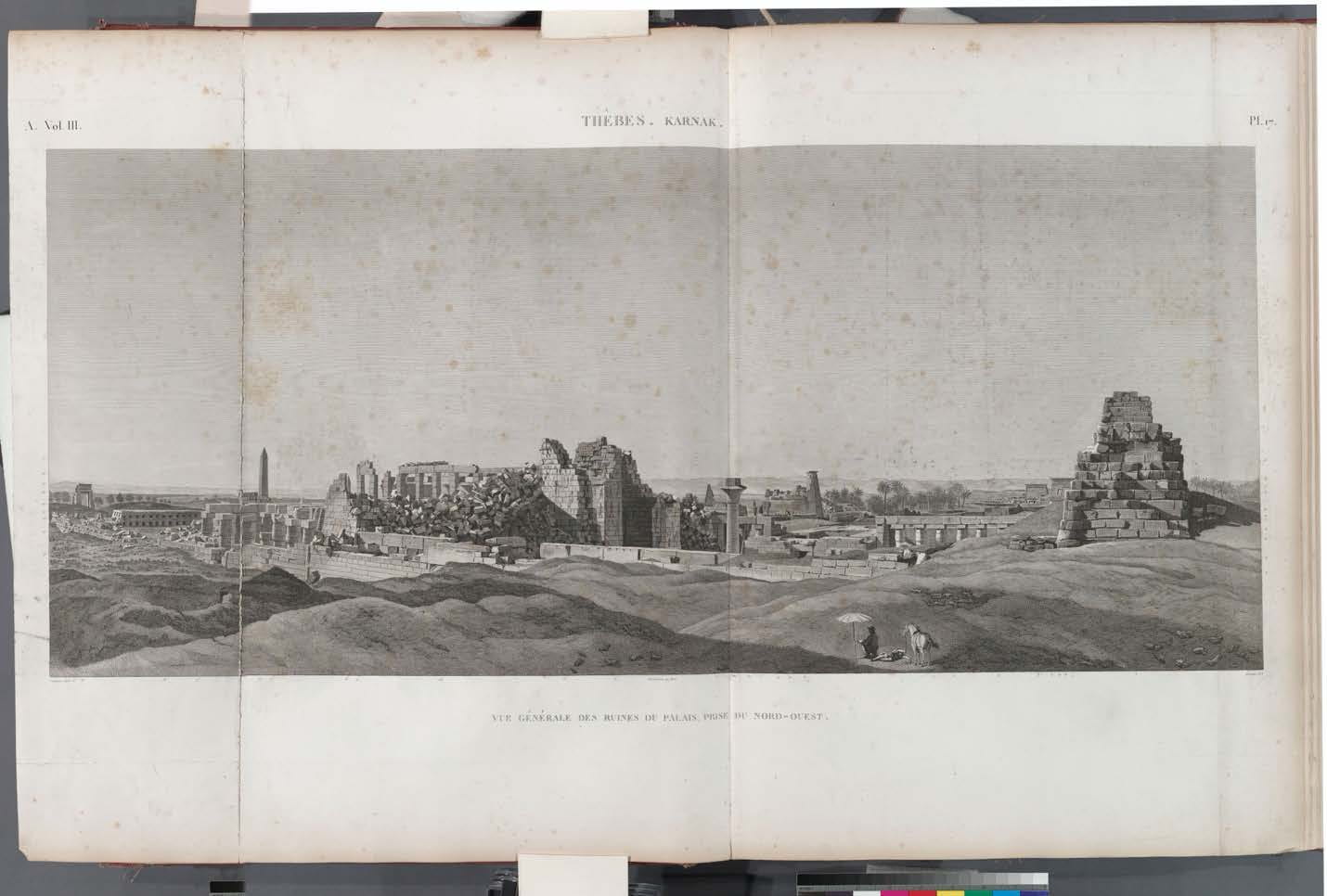

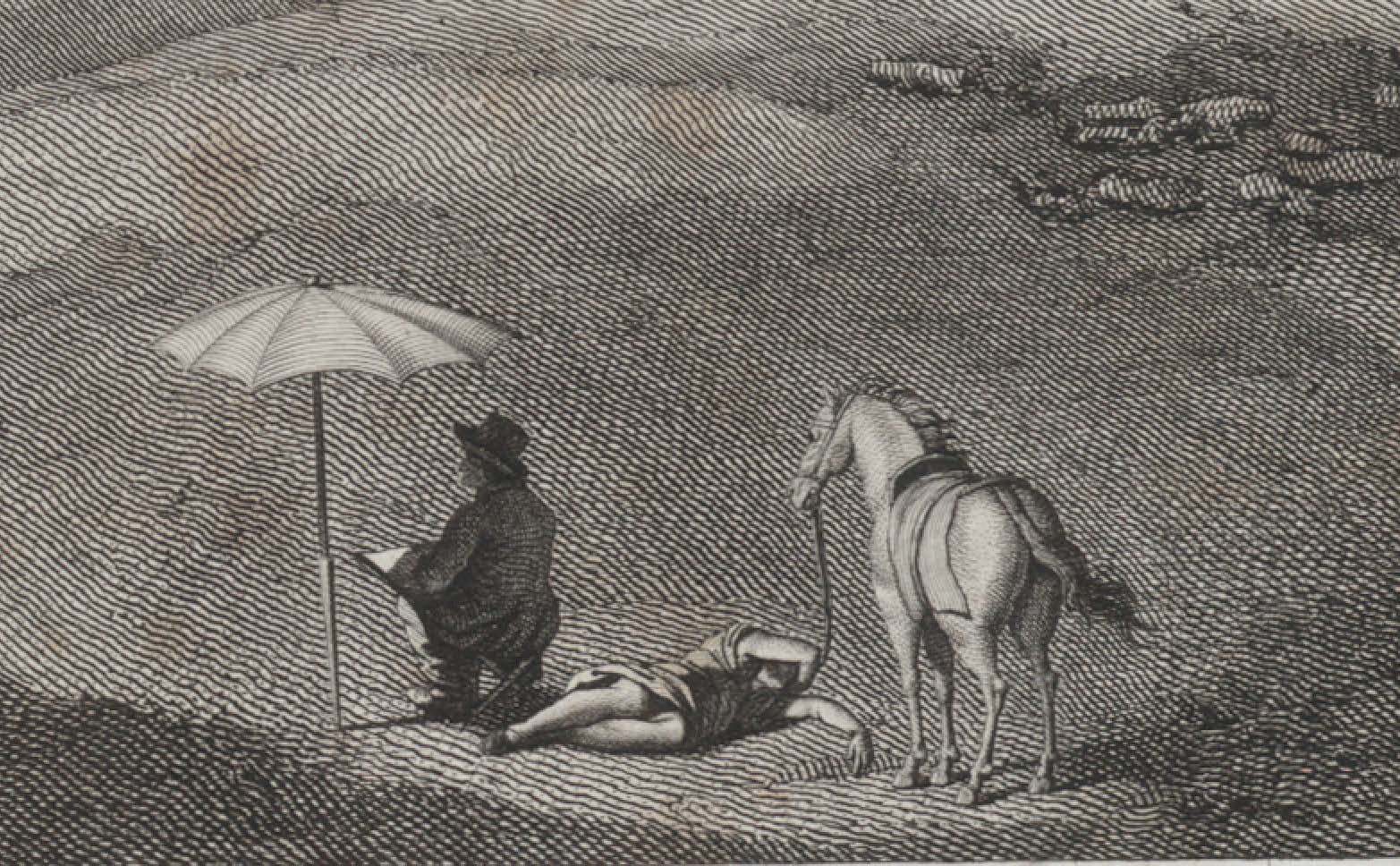

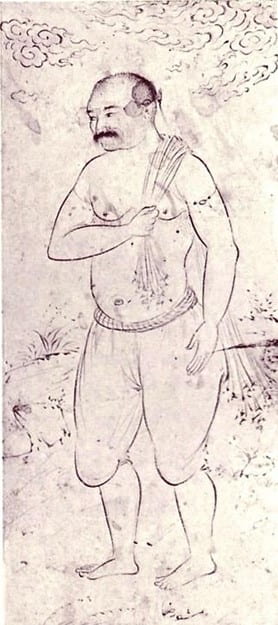

In fact, many prints are a collage of several sketches, often produced by different savants. Plate 17 from Volume III is a landscape scene of Karnak (Fig. 17). In the foreground of the print (Fig. 18), a savant is seen sketching next to a female sprawled seductively on the sand holding onto the reins of the horse. Of this vignette, Godlewska writes, “Here fantasy, the erotic and the exotic are all combined to relieve any tedium attached to antiquities. It also suggests, however, something of the complex motivations and emotions associated with the conquest of Egypt.”[xxi] Godlewska attributes the female odalisque to André Dutertre, the savant responsible for the drawing. However, these figures are not in Dutertre’s original drawing (Fig. 19); they had been copied from a sketch by François-Charles Cécile (1766–1840), a mechanical engineer (Fig. 20). This sketch has no context, and it is not clear if it was drawn at Karnak. Yet, it was included in the scene to add visual interest to the landscape while also maintaining the illusion of ‘the real.’

Fig. 17 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 17. Vol. III, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Fig. 18 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 17. Vol. III, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

![Fig. 19 Dutertre, [Karnak] : [vue générale des ruines du palais, prise du nord-ouest], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-19-1024x397.jpg)

Fig. 19 Dutertre, [Karnak] : [vue générale des ruines du palais, prise du nord-ouest], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

![Fig. 20 Cécile, [Dessinateur à l’ombre d’un parasol], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre et plume. 11.3 x 11.9 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-20-967x1024.jpg)

Fig. 20 Cécile, [Dessinateur à l’ombre d’un parasol], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre et plume. 11.3 x 11.9 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

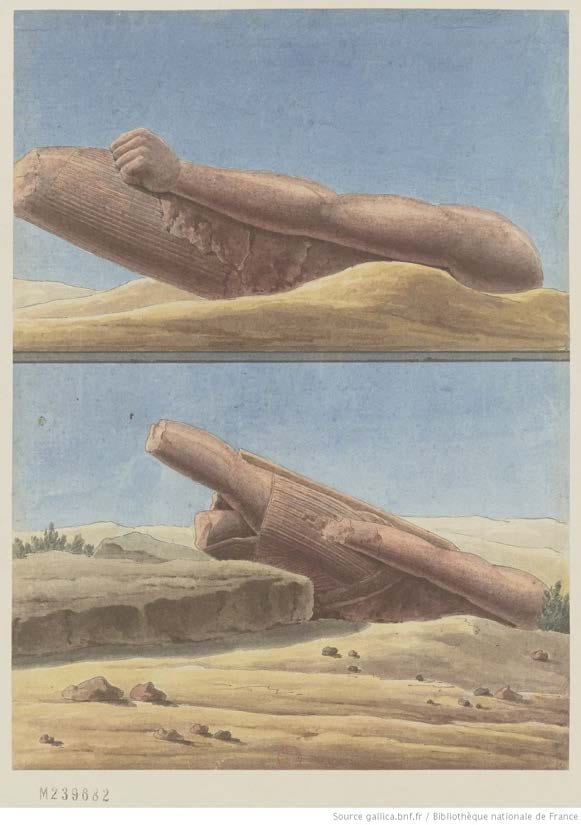

Fig. 21 Charles-Louis Balzac, [Karnak] : [fragments de colosses trouvés dans l’enceinte sud], 1798- 1809, aquarelle et plume. 27.5 x 20 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

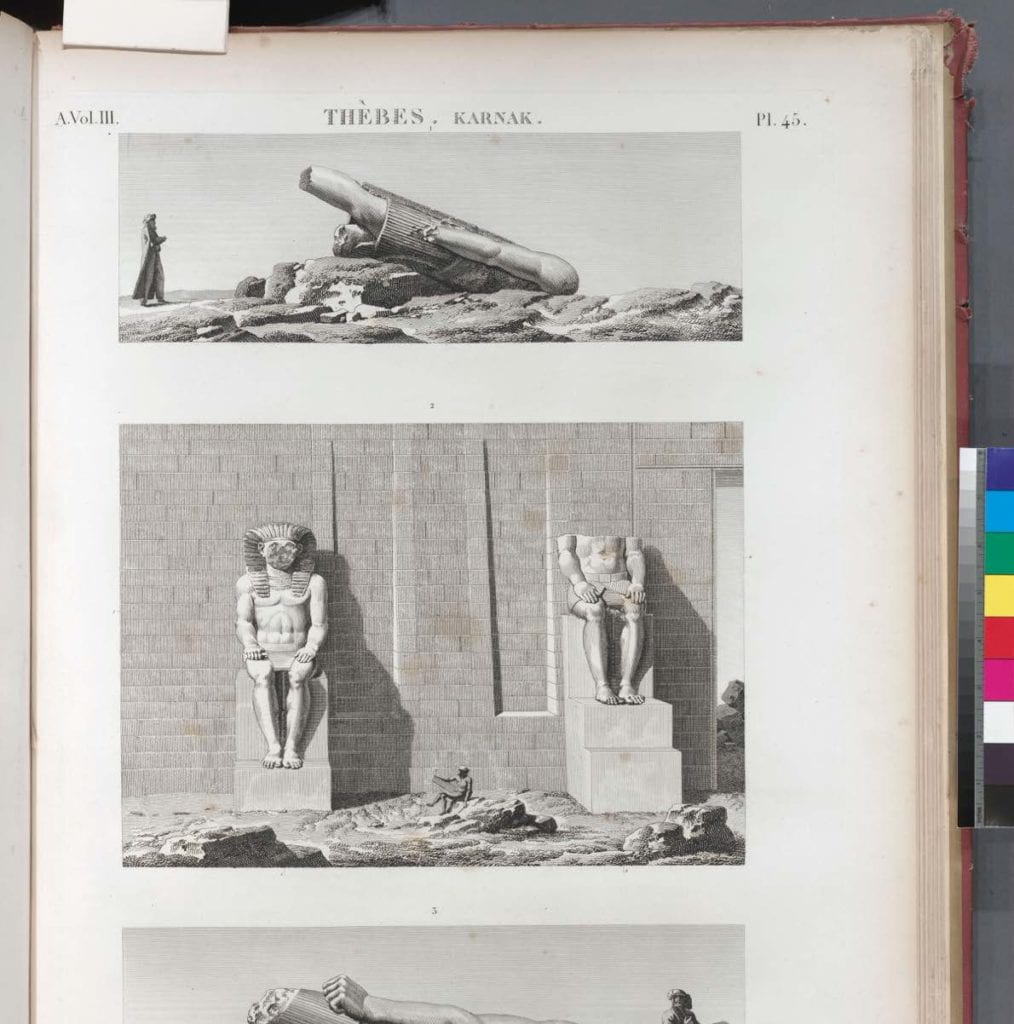

Fig. 22 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 45. Vol. III, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

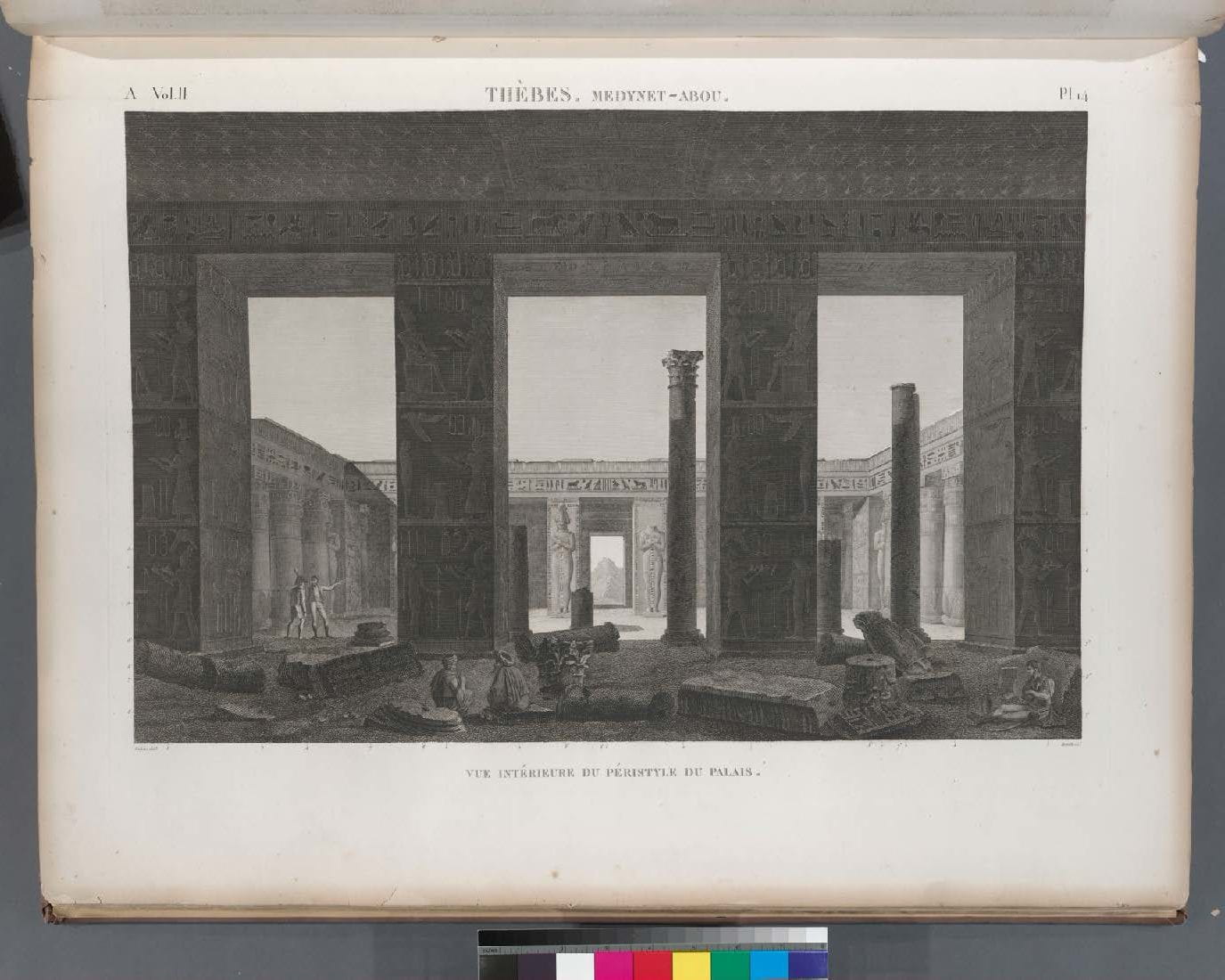

The creative agency of the engravers is most evident in the scenic depiction of the inner court of the temple at Médinet Habou. Plate 14 (Fig. 23) was engraved by Reville, based on a drawing by Balzac. The drawing (Fig. 24) is markedly different from the print. Several key architectural features have been reversed as well as the position of the figures in the foreground. In the engraving, the two columns have switched sides as well as the statues flanking the entrance to the second court. The pair of savants has changed positions with the seated savant. The fragments of statuary on the ground have shifted in relation to the figures. A possible explanation for these adjustments is that intaglio images print in reverse. When preparing the plate, the engraver draws the images in reverse so that the printed image is in the correct orientation. This engraver may have neglected to take this into consideration when transferring the drawing to the plate, due to inexperience or for another technical reason. Yet, the midground temple scenery from the drawing was not reversed accordingly in the print. The left side of the drawings does not correspond to the right side of the print and vice versa. In fact, close examination reveals that the architectural features of the temple do not follow Balzac’s record. One can interpret these adjustments as an attempt to compress the drawing, which is wider than the printed image. The drawing was compressed by the engravers to make the most use of the available space on the printed page.

Fig. 23 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 14. Vol. II, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

![Fig. 24 Balzac, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-24-1024x714.jpg)

Fig. 24 Balzac, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

![Fig. 25 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-25.jpg)

Fig. 25 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 26 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 14. Vol. II, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

![Fig. 27 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-27.jpg)

Fig. 27 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 28 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 14. Vol. II, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

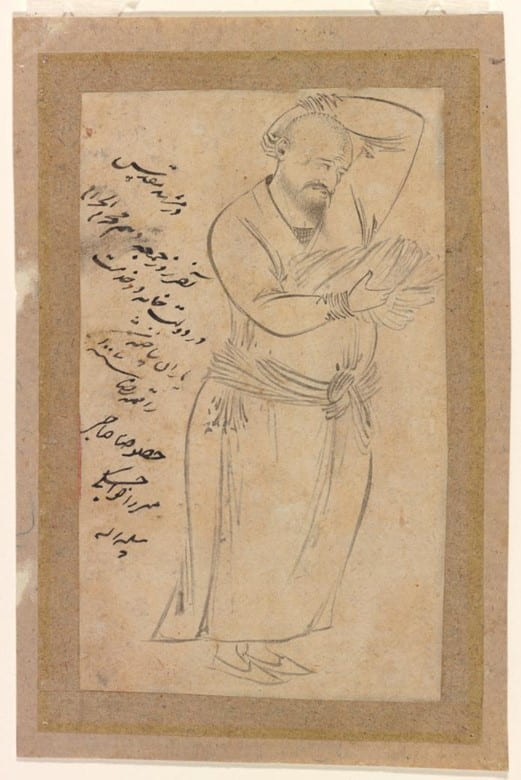

The Egyptian figures have also been altered for the engraving. In the drawing (Fig. 29), both men are bearded and wear trousers, a long-sleeved shirt, and a vest. The figure on the right wears a turban and smokes a long pipe. The figure on the left wears a Western style hat with a wide round brim, suggesting that he may in fact be French. In the engraving (Fig. 30), both men wear traditional Muslim garments, consisting of billowing tunics and turbans. Prochaska notes that nowhere in the Description are French and Egyptian figures shown interacting. He also notes that they are most often placed in different quadrants of the scenes. If they are depicted in proximity to one another, the Egyptian is acting in service to the French invaders. The prevailing French narrative of conquest is supported by such encounters between East and West.

![Fig. 29 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d'encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/1/12638/files/2021/06/Fig.-29.jpg)

Fig. 29 Jollois et de Villiers, [Médinet Habou] : [vue intérieure du péristyle du palais], 1798-1809, lavis d’encre, plume et crayon. 37.1 x 57.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris, France.

Fig. 30 Description de l’Égypte, Plate 14. Vol. II, 1812, engraving on paper, 70 x 51 cm. New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Though presented as a complete and unified work, the Description is the creation many groups of authors, savants, and engravers alike, over a period of decades and separated by thousands of miles. The network of print workshops struggled with the challenge of depicting hundreds of ancient Egyptian monuments in a medium designed to convey traditional Western architecture to a European public wholly unfamiliar with such non-Western styles and principles. The awesome scope of the project inevitably resulted in accuracies and interpretive license. Yet, these images continue to influence study of ancient Egypt in both their print and digital forms. The Description is a testament to a historiographic moment in the development of Egyptology and a massive artistic and logistical accomplishment. The legacy of the Description de l’Égypte endures, as its images continue to spark delight and inspire awe.

[i] Michael Albin, “Napoleon’s Description de L’Egypte: Problems of Corporate Authorship.” Publishing History 8 (January 1, 1980), 65–85.

[ii] David Prochaska, “Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description de l’Égypte (1809–1828).” L’Esprit Créateur 34, no. 2 (1994), 69–91.

[iii] Anne Godlewska, “Map, Text and Image. The Mentality of Enlightened Conquerors: A New Look at the Description de l’Egypte.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 20, no. 1 (1995), 5.

[iv] Godlewska, “Map, Text and Image,” 9.

[v] Henry Petroski. The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance. 1st ed. (New York: Knopf: Distributed by Random House, 1990), 70.

[vi] Richard Taws, “Conté’s Machines: Drawing, Atmosphere, Erasure,” Oxford Art Journal 39, no. 2 (August 2016), 252–254.

[vii] Ibid, 256.

[viii] Ibid, 256.

[ix] Fernand Emile Beaucour, Yves Laissus, and Chantel Orgogozo, The Discovery of Egypt (Paris: Flammarion, 1993), 140.

[x] Godlewska, “Map, Text and Image,” 11.

[xi] Ibid, 17.

[xii] Ann D’Arcy Hughes and Hebe Vernon-Morris, The Printmaking Bible: The Complete Guide to Materials and Techniques (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008), 82.

[xiii] Bamber Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical

Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet, 2nd ed (New York, N.Y: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 9b.

[xiv] Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints, 9a.

[xv] Taws, “Conté’s Machines,” 256.

[xvi] Ibid, 259.

[xvii] Beaucour et al., 146.

[xviii] Charles Coulston Gillispie, “Notes,” 2.

[xix] Rebecca Zorach, Paper Museums: The Reproductive Print in Europe, 1500–1800. (Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2005), 16.

[xx] Linda Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” in The Politics of Vision: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Art and Society (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 38.

[xxi] Ibid, 22.

[xxii] Prochaska, The Pencil, 84.

Katherine Parks is a book conservator in New York. She was the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Library & Archive Conservation at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University where she received her MA in Art History and MS in Conservation in 2020. She has held positions at the Library of Congress, Columbia University Libraries, and will be joining Cornell University Library as the Conservator for Rare and Distinctive Collections in the fall of 2021.

The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; Palmer School of Library & Information Science, Long Island University

This paper examines imagery of transparency in the convent of Katharinenthal, discussing a sculpture of the Visitation carved for the convent around 1310-20, and the Katharinenthal Sister Book. The sculpture is unusual in its use of two rock-crystal cabochons to represent the pregnancies of the Virgin Mary and her relative, Elizabeth. The Sister Book records a chronicle of the founding of the convent, as well as vitae memorializing the lives of deceased sisters and describing their religious visions, several of which feature a motif of transparency. Multiple sisters are recorded as becoming “as clear as crystal,” while another sister beholds a vision of “the wall of the refectory appear[ing] as though it were glass.”