Ximena Kilroe

City College, City University of New York

Abstract

In May 1914, poet Nicholas Vachel Lindsay debuted his poem “The Congo: A Study of the Negro Race,” in which he imagined the journey of Africans from so-called savagery to redemption brought by civilizing angels. The poem quickly garnered popularity and was reproduced widely, including in The Golden Book Magazine, where it was printed alongside six etchings by Harlem Renaissance artist James Lesesne Wells. These prints have been either disregarded or cast aside as problematic anomalies within considerations of the artist’s oeuvre. This paper examines Wells’s prints against the backdrop of the critical responses to Lindsay’s poem by figures such as W. E. B. Du Bois and in comparison with his other works that depict Africa, reframing Wells’s “Congo” prints as works in which the artist engaged with discourses prevalent during the Harlem Renaissance and articulated his own beliefs about Africa.

![]()

Between the Congo and Ethiopia:

Africa and the Prints of James L. Wells, 1927–1929

In May 1914, poet Nicholas Vachel Lindsay performed his poem “The Congo: A Study of the Negro Race” in his hometown of Springfield, Illinois. Divided into three parts—“Their Basic Savagery,” “Their Irrepressible High Spirits,” and “The Hope of Their Religion”—the poem imagines the transformation of Africans from what Lindsay sees as savagery to redemption, brought about by civilizing “pioneer angels.”[1] For Lindsay, the culmination of the redemption of indigenous Africa, metaphorically represented by the Congo, is best expressed in the second-to-last stanza of the final section, where he declares, “Mumbo-Jumbo is dead in the jungle. Never again will he hoo-doo you.”[2] This poem quickly became Lindsay’s most popular work, drawing both praise and criticism in its time, and has since been consistently performed and reproduced in periodicals and books.

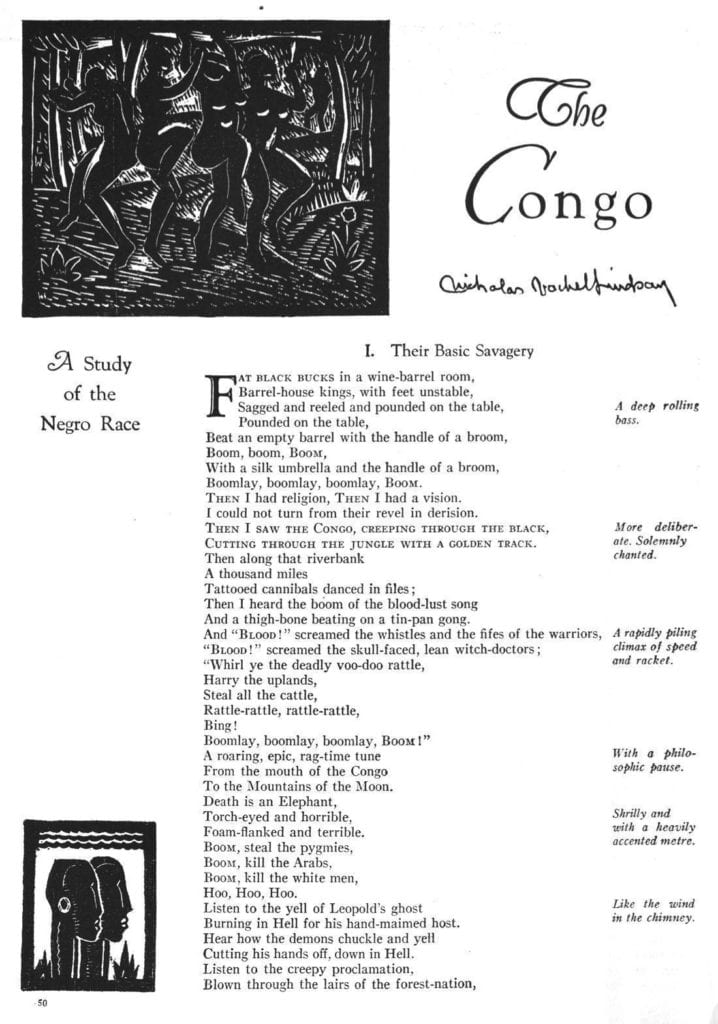

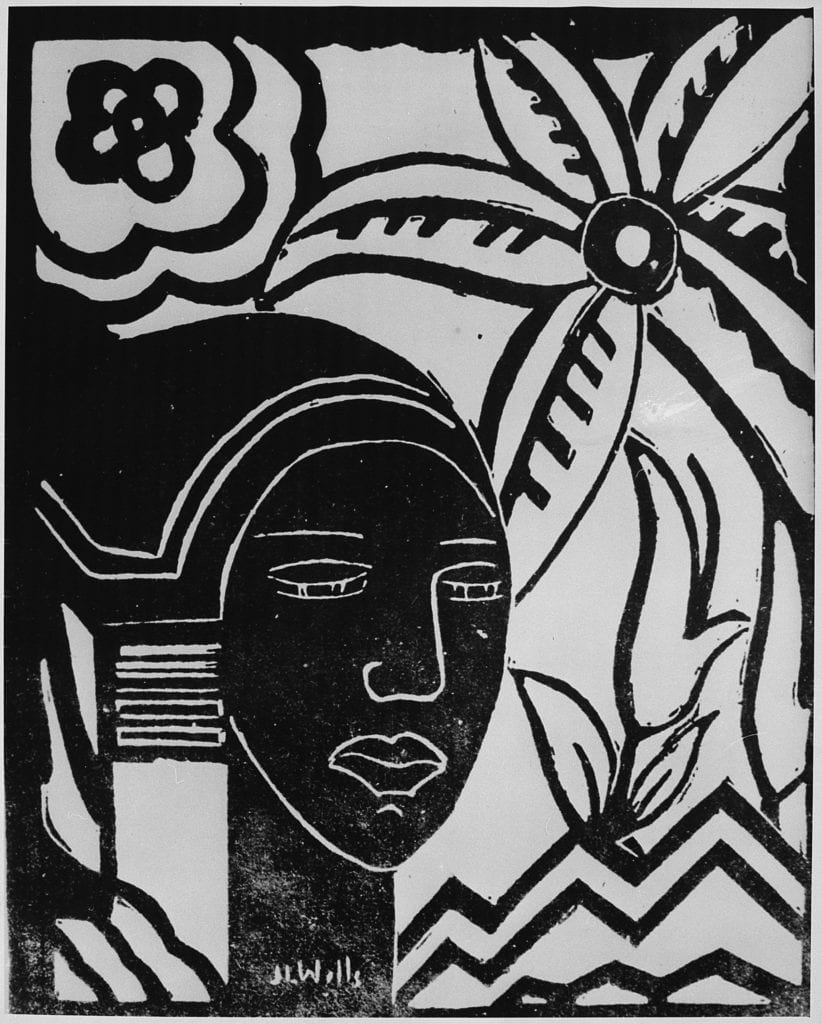

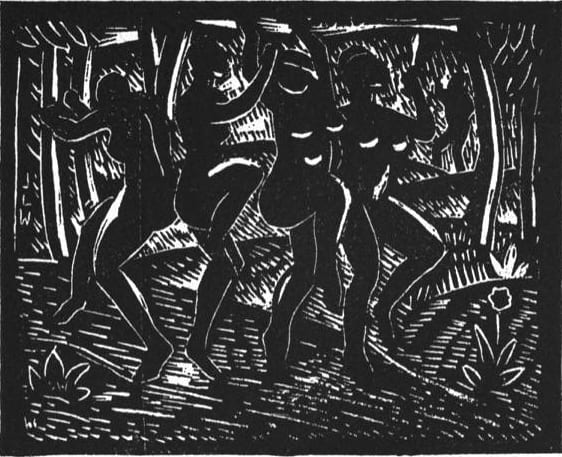

One publication in which “The Congo” was reprinted is the September 1929 issue of The Golden Book Magazine (Figs. 1 and 2). Published together with the poem were six linoleum cut prints by James Lesesne Wells, an artist then well known within the community of writers, artists, and thinkers of the Harlem Renaissance. Using what the artist described as an “African aesthetic” that drew inspiration from the geometric and generalized forms of the African art he encountered at the Brooklyn Museum,[3] these prints were most readily accepted as visual counterparts to the primitivizing rhetorical style and themes used by Lindsay to describe life in the Congo.

Figure 1. Page 50 of The Golden Book Magazine 10, no. 57 (Sept. 1929).

Figure 2. Page 51 of The Golden Book Magazine 10, no. 57 (Sept. 1929).

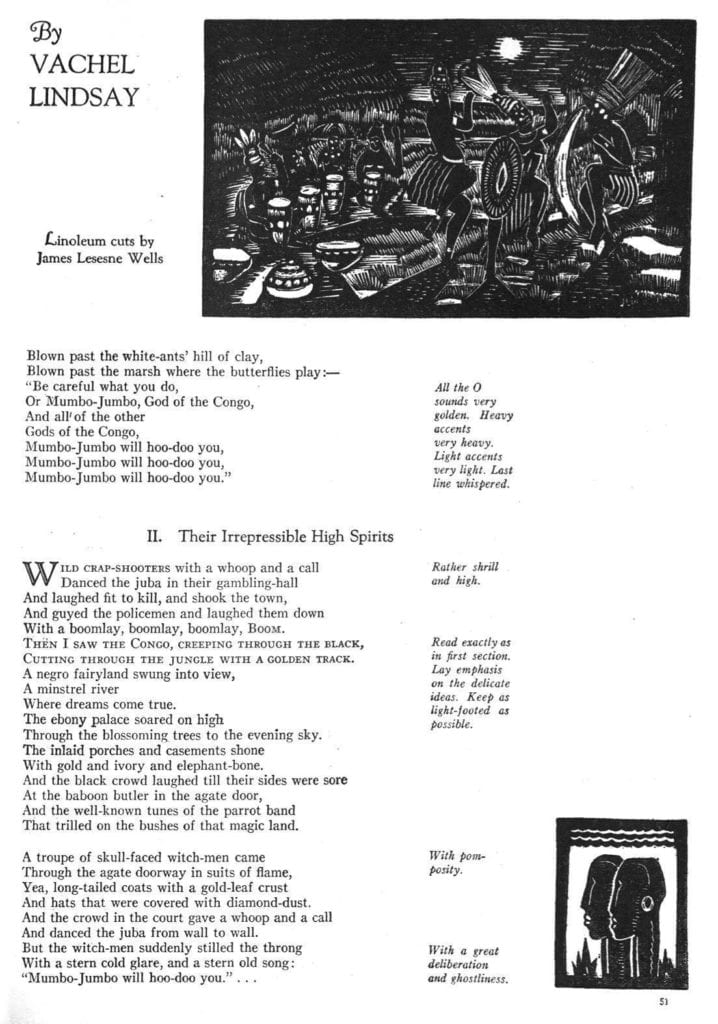

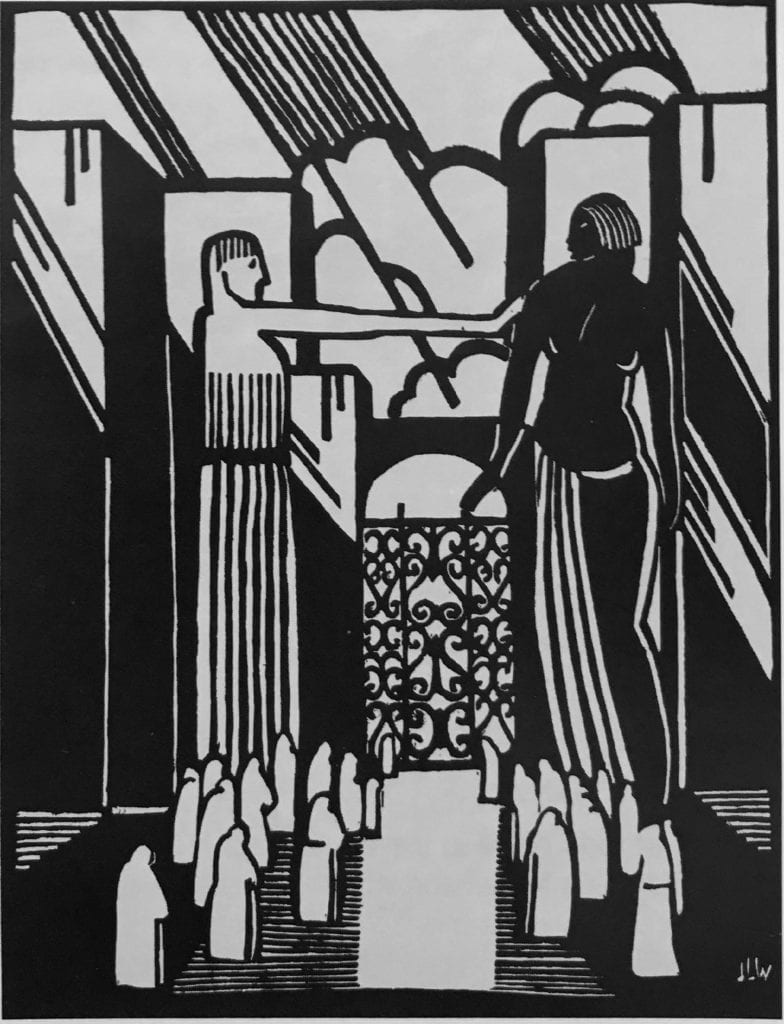

Like many artists of the Harlem Renaissance, Wells made prints that were specifically meant to be printed as illustrations to accompany texts, as in the case above, or as full page images intended to convey the broader message of a publication and its editors. An example of the latter is Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice (Figs. 3 and 4), a set of two prints; the first was prominently featured in the November 1928 issue of the NAACP’s official magazine, The Crisis,[4] while the second was featured as the cover of Plays and Pageants from the Life of the Negro.[5] Despite the fact that such prints formed a significant part of the artist’s oeuvre made while he was living in New York—he moved to Washington, D.C., to teach at Howard University in 1930—scholars have largely ignored such works in favor of either his early paintings or his standalone prints addressing the role of African Americans in American industrial labor. Wells’s “Congo” prints, when mentioned, are typically framed either as problematic or as anomalies within the artist’s oeuvre.[6]

Figure 3. James L. Wells, Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice, 1928, linoleum cut print.

Indeed, the only text to examine such works closely is Caroline Goeser’s chapter, “ ‘To Smile Satirically’: On Wearing the Minstrel Mask,” which focuses on Wells’s pieces in The Golden Book Magazine. Goeser argues that in these works Wells replaced stereotyped caricatures with what she terms “savvy tricksters” that undermined Lindsay’s racist views. This analysis allows her to recuperate the prints and Wells from conventional readings of these works as problematically creating a primitive imagining of Africans. Yet in doing so, Goeser neglects to examine Wells’s “Congo” prints in relation to his other prints for publications, such as Ethiopia, or even standalone prints that also engaged with African motifs in the late 1920s, such as African Phantasy (Fig. 5). She further neglects to consider the critical discourses that concerned the imagining of Africa by both whites and African Americans, within which the generalized metaphors of the Congo and Ethiopia were instrumentalized toward derogatory and celebratory ends, respectively. A close examination of the discourses surrounding Wells during the making of the “Congo” prints, and of their relationship to other African-inspired works the artist created during the same period, will provide a different reading: that Wells, in these prints, attempted to navigate the envisioning of Africa as the site of a utopic past on the one hand, and of a contemporary, “primitive” place in need of black American leadership on the other. Such an analysis firmly places the prints within the artist’s oeuvre as works in which he negotiated and articulated his own beliefs about Africa, rather than as problematic anomalies.

Figure 4. James L. Wells, Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice, 1928, linoleum cut print.

Figure 5. James L. Wells, African Phantasy, 1927, linoleum cut print. National Archives Catalogue.

The Critical Reception of “The Congo”

In order to fully understand the implications of Wells’s prints appearing with Lindsay’s “The Congo,” the range of responses to the poem by both contemporaries and later scholars must be considered. Among the contemporary African-American critics of the poem was W. E. B. Du Bois, who wrote in the August 1916 issue of The Crisis that “Mr. Lindsay knows two things, and two things only about Negroes: The beautiful rhythm of their music, and the ugly behaviors of their drunkards and outcasts . . . Mr. Lindsay knows little of the Negro, and that little is dangerous.”[7] “The Congo” was further criticized a year later by Joel Spingarn, president of the NAACP. In a letter to Lindsay, he wrote, “I wish you had been able to attend the Amenia Conference, and perhaps then you would have understood the difference between a poet’s pageantry and a people’s despair.”[8] Significantly, Du Bois and Spingarn are both particularly critical not necessarily of the poem itself, but of Lindsay’s performances. Accounts of his performances describe how Lindsay would “throw back his head and . . . emit his barbaric Boomlays . . . his eyes roll like a man’s in a fit and his hands shoot from the cuffs of his dress suit.”[9] The extant audio recordings of Lindsay reciting the poem together with the performance instructions published in its margins support such characterizations. It is on the basis of these criticisms and recollections that later scholars such as Susan Gubar argue that Lindsay demonized African Americans.[10] Rachel Blau DuPlessis adopts a similar position, interpreting Lindsay’s mimicry of minstrel rhythm as the poet arguing “that the menace and luring evil of Africa can never be extirpated,”[11] despite Lindsay’s statements to the contrary.[12]

Although Gubar and DuPlessis offer salient points, they take the criticisms of figures such as Du Bois and Spingarn as points of departure without either nuancing them or contextualizing them within broader cultural conversations. Indeed, while Du Bois’s and Spingarn’s criticisms offer important context with regard to the contemporaneous responses to Lindsay’s poem, they were not wholly critical; “The Congo” as a poem was not immediately condemned as problematic. This is evidenced by Du Bois’s first response to “The Congo,” in the May 1915 issue of The Crisis, published before Du Bois had seen the work performed.[13] There, he wrote that although “colored readers may be repelled at first by Lindsay’s great poem . . . it is, in its spirit, a splendid tribute of spiritual insight.”[14] This admission of spiritual insight, coupled with his later concession that Lindsay held an understanding of black rhythm, reveals the complicated nature of contemporary discourse surrounding “The Congo.” It suggests that the outrage surrounding the poem lay not in the envisioning of Africa as primitive or in the replication of so-called African rhythms as a stylistic device, but in Lindsay’s performance of a “counterfeit expression of the Negro.”[15] This reading finds support in Du Bois’s own beliefs regarding contemporary indigenous Africans as primitive and in need of African-American leadership in order to be modernized and redeemed: in an article in The Atlantic, also published in May 1915, he wrote, “We must train native races in modern civilization . . . This we have seldom tried. For the most part Europe is straining every nerve to make over yellow, brown, and black men into docile beasts of burden.”[16] His words echo the exceptionalism found among black American leaders who suggested that they could civilize indigenous Africans; despite attempts to differentiate their ideas from European colonial rhetoric, they continued to instrumentalize the narrative that positioned native Africans as primitive and uncivilized.[17] Du Bois’s position confirms scholar Paul H. Gray’s argument that what are now taken as indicators of bigotry came in Lindsay’s time “not from racists, but from brilliant and sophisticated black artists,” as well as writers and thinkers.[18] For instance, James Weldon Johnson’s song “Congo Love Song” imagines “the wilds of Umbagooda,” a fictitious place used to imbue the Congo with a sense of primitivism.[19] Du Bois’s thoughts on Africa ultimately offer insight as to why he had two seemingly contradictory responses to Lindsay’s “Congo,” and demonstrates how he was able to support the poem on the one hand while condemning the performances on the other.[20] It is against this complex critical background that Wells’s accompanying prints must also be read, especially if, as the artist stated, “My belief is that art has a social message and should be expressive of the artist’s reaction to society.”[21]

Wells’s “Congo” Prints

Of the six prints Wells made to accompany “The Congo,” three visually represent what is happening in the poem, with two specifically imagining indigenous Africa. The first work that does so is Untitled (Fig. 6), which appeared beside the title of Lindsay’s poem along with the majority of the first section, “Their Basic Savagery.” The print shows four women dancing naked, surrounded by rolling hills and trees. The figure on the far right has her mouth open as if shouting, representing the screams and yells of Africans in the poem. Similarly, the second print, featured on the opposite page (Fig. 7), shows four figures on the left playing the drums, another aspect of Lindsay’s vision of Africa emphasized in the first section. Both prints are primarily black, with white used to outline shadows and forms that would typically be represented through variations in tone, as can be seen on the trees and on the breasts of the figures on the left. Alternatively, as in the case in the second print, white is used to draw attention to the elements of the composition intended to signify indigenous culture, such as drums and headdresses. Together, the images picture the heart of the first section, in which Lindsay writes: “Then I saw the Congo, creeping through the black, cutting through the jungle with a golden track. Then along that riverbank; a thousand miles; Tattooed cannibals danced in files; Then I heard the boom of the blood-lust song; And a thigh-bone beating on a tin pan gong. And ‘Blood!’ screamed the whistles and the fifes of the warriors.”[22]

Figure 6. James L. Wells, Untitled, 1929, linoleum cut print.

Figure 7. James L. Wells, Untitled, 1929, linoleum cut print.

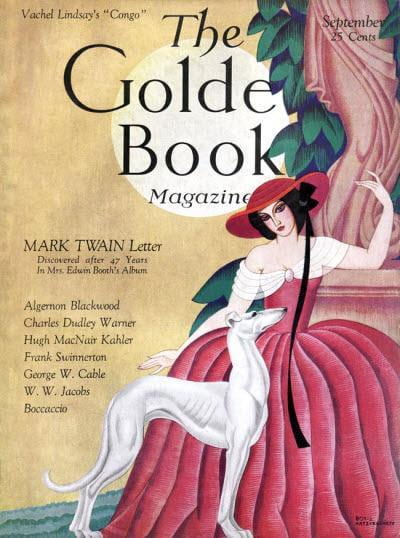

In her reading of these prints, Goeser argues that the raised-leg posture of the dancing figures in the first work is a reference to a dance step called “jump Jim Crow,” which was popularized in blackface minstrels in nineteenth-century America. She argues that by representing the figures in this pose, Wells was satirizing Lindsay’s imagery and performance to “mock the hackneyed stereotypes at the heart of the poem.”[23] While Goeser’s connection between the figures in Wells’s prints and “jump Jim Crow” is compelling, her conclusion that the images were meant as correctives to Lindsay’s poems and succeeded as such neglects to consider the audience of The Golden Book Magazine. The magazine’s readership, which at its height reached only 135,000, was primarily white and upper middle class. This demographic was targeted in the magazine’s content and graphic design.[24] For example, the cover of the issue that featured Lindsay’s poem shows a white woman in Victorian dress with a greyhound (Fig. 8). She stands in front of a pink sculpture on a pedestal surrounded by ivy, both indicators of wealth and classical Western culture. This audience—which historian Frank Luther Mott notes was unreceptive to the more experimental texts included in the publication—was unlikely to have understood Wells’s prints as satirical. Goeser’s argument that the prints successfully enacted a critique of the poem is therefore unlikely.

Figure 8. Unknown illustrator, cover of The Golden Book Magazine, Sept. 1929.

Further lacking in Goeser’s analysis of Wells’s prints is an understanding of the artist’s own views regarding indigenous Africa. Wells recounted in a 1986 interview with Richard Powell and Joshua Reynolds that Du Bois and his ideas were formative for him for the brief period between when he graduated from Columbia in 1927 and when he began teaching at Howard University in January 1930: “My most interesting connection was with W. E. B. Du Bois. Working with him, he was assertive about his ideas. He was a very brilliant man and influenced me greatly as a young man.”[25] Given his admiration of Du Bois, it is likely that Wells knew of his views regarding indigenous Africans and the role he thought African Americans could play in civilizing them. The artist also described his works inspired by contemporary Africa as having an “essentially Third World sense.”[26] Taken together, these statements indicate Wells’s general agreement with Du Bois’s opinions regarding the primitiveness of contemporary indigenous Africa. Goeser’s argument that the artist’s “Congo” prints were meant to be correctives to the problematic language of Lindsay’s poem is thus questionable, given Wells’s own opinions and his belief that art should reflect the artist’s responses to societal discourses.

Egyptomania and Ethiopianism in the Harlem Renaissance

While Wells’s presumed opinions about Africa make Goeser’s argument unlikely, this does not mean that the artist was firmly in support of the message behind Lindsay’s work. Rather, like Du Bois, Wells’s views regarding Africa were complicated, as exemplified by his engagement with the concepts of Egyptomania and Ethiopianism.[27] In the context of African-American discourse, Egyptomania refers not to the eighteenth-century European obsession with Egypt, but to the use and instrumentalization of Egyptian forms to take on a new contemporary significance.[28] Meanwhile, Ethiopianism has roots going back to the beginning of slavery, when Ethiopia gained significance for African Americans in large part due to the Biblical verse Psalms 68:31: “Ethiopia shall stretch out her hands toward God.”[29] Ethiopianism, like Egyptomania, symbolized an idealized African past, a place of “singular black power and special promise . . . second only perhaps to dynastic Egypt.”[30] These ideas became part of the African-American intellectual community as early as the 1870s, when intellectuals in the post–Civil War era attempted to articulate new dual identities that were both American and African.[31]

Du Bois played a major role in popularizing these ideas in the 1910s and 1920s within the context of the Harlem Renaissance. For instance, Du Bois supported the idea that framed ancient Egypt as the black counterpart to ancient Greece.[32] Similarly, Du Bois instrumentalized the metaphor of Ethiopia to advocate for a return to an imagined idyllic African past; by looking at the high points of its past, Africa could achieve a utopic future.[33] Both these ideas are emphasized in his 1913 pageant, “The Star of Ethiopia.”[34] The pageant is divided into six scenes, titled “Introduction,” “The Culture of Egypt,” “The Black Man Rules the World,” “The Land of the Blacks,” “The Search for the Star of Freedom,” and “The Tower of Light.” In the first section, Du Bois introduces his character Ethiopia, who comes across “savages,” some of which begin the journey toward becoming civilized through her instruction.[35] The second section continues the narrative of those who chose to follow Ethiopia, showing the greatness of ancient Egypt, described as “first civilization in the world.”[36] The remaining sections cover various events in African history, including the rise of Islam and the arrival of Europeans. During these scenes, Ethiopia is described as dejected and as rejecting these new arrivals on the continent. The final two sections address the attempts to recover Ethiopia’s star of freedom, through which Africans can begin to return to the greatness of the path set by Ethiopia, exemplified by Egyptians in the second section. By making Ethiopia the allegorical protagonist, and ancient Egypt the exemplar of an African civilization that followed her, Du Bois staged a play that foregrounded the driving ideas behind both Egyptomania and Ethiopianism.

Wells on Egypt and Ethiopia

Du Bois further promoted these ideas through his editorial choices at The Crisis, notably via the illustrations he included the publication. Among these was a print by Wells, which was prominently featured in the November 1929 issue. One of a set of two works collectively titled Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice, the image shows Ethiopia, represented by the tall black female figure on the right, as being denied access to Justice by the white figure on the left, who raises his arm up to stop her. The second print, which was not included in the publication, shows Ethiopia successfully reaching Justice, represented by the seated black figure. Although Wells never directly spoke about his work as engaging with Ethiopianism, the work speaks allegorically to the notion within Ethiopianist thinking that posited a return to past greatness through the undoing of colonialism—considered a “great injustice against the teeming millions of Ethiopia’s sons”[37]—as promised in the Bible.[38] That Justice in the second print is also a black figure can therefore be understood within the narrative of Ethiopianism as Wells’s visual representation of the promised justice and redemption. Wells’s close engagement with and admiration of Du Bois, along with the fact Du Bois chose one of these prints to be reproduced in The Crisis, signals the artist’s likely engagement with such ideas. This conclusion is further supported by Wells’s opinion that art should reflect an artist’s social beliefs.

Within Ethiopia and the Bar of Justice, Wells also indicated his engagement with the ideas promoted by Du Bois regarding Egypt, predominantly through the use of stylistic techniques inspired by ancient Egyptian aesthetics. The figures in Ethiopia are represented in a highly stylized manner. The second print, with the emphasis placed on flattening the figures and showing them in profile, can be visually linked with the flattening of ancient Egyptian art. The aesthetic nods in Ethiopia allude to Egyptian culture at the moment when it was considered an “African golden age,” thus signaling the artist’s awareness of the status given to ancient Egypt in African-American thinking at the time.[39]

Aesthetic inspiration drawn from ancient Egypt can also be seen in other works from this period, including African Phantasy, which Wells later described as one of his most successful prints of the late 1920s.[40] The figure in African Phantasy is represented as a stylized head with a long neck. Importantly, the subject wears a headdress similar to those worn by figures in ancient Egyptian art, alluding to Egyptian culture. The background, full of blooming flowers, indicates that the fantasy referenced in the title is one of abundance and, if read through the metaphor of Egypt, as one of a utopic past. The title, too, could be understood as a fantasy of the future; the work is temporally ambiguous. Ultimately, when understood within the historical context in which it was made, African Phantasy evidences Wells’s support of the narratives surrounding Egypt as articulated by African-American intellectuals such as Du Bois. Wells’s decision to aesthetically allude to ancient Egypt in both the set of Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice and African Phantasy must then be understood as a deliberate means through which he aimed to communicate support of the ideas of Egypt and Ethiopianism. Thus, like those of Du Bois, Wells’s ideas surrounding Africa are not clear cut, but rather show his engagement with the intellectual conversations surrounding him in Harlem.

Nuancing the “Congo” Prints

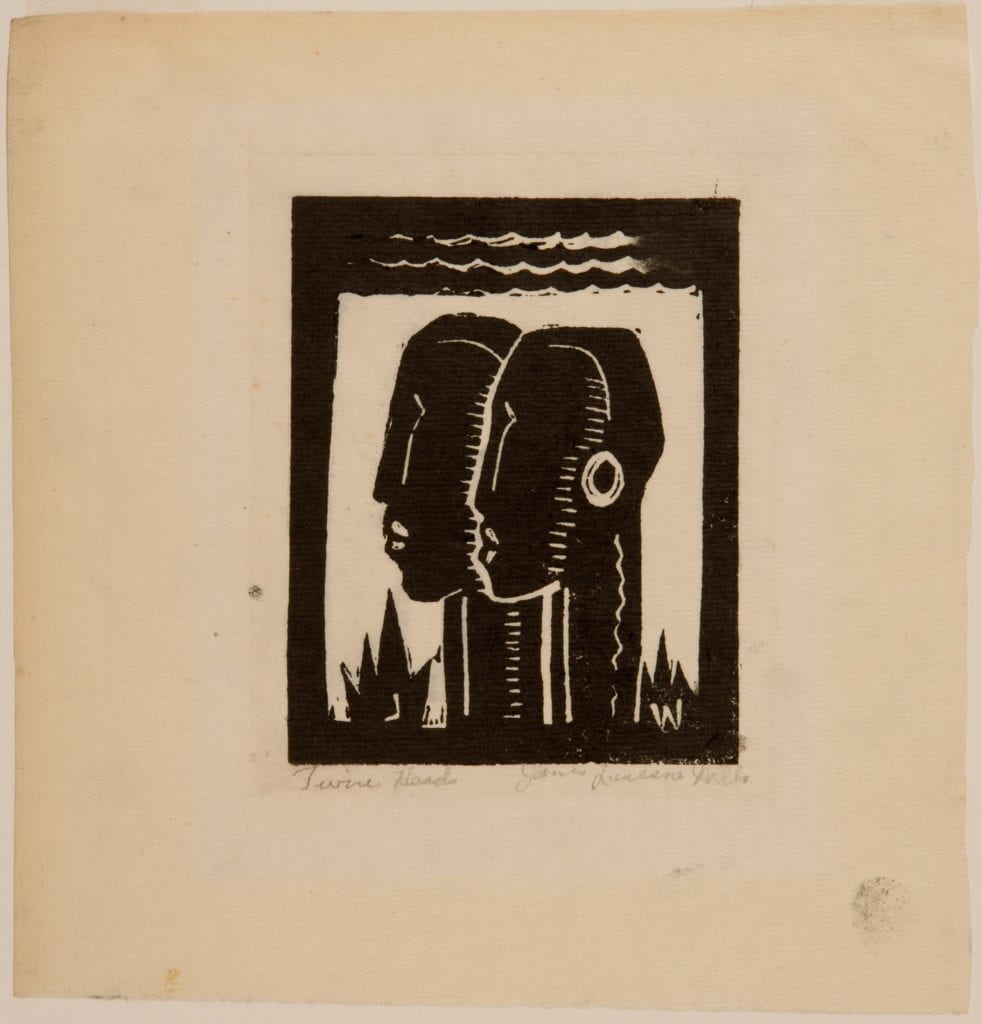

If Wells’s works aesthetically inspired by Egyptian art are understood to engage with notions of Ethiopianism, his contributions to “The Congo” can be further complicated, notably through the print that lacks a direct correlation with the narrative of the poem, Untitled (Twin Heads) (Fig. 9). The work shows two stylized heads facing left, in flattened profiles again formally related to ancient Egyptian art. The figures’ bodies are not represented, save for their extremely long necks that help place the heads compositionally between the clouds along the top border and the two bushes of grass below them. Aesthetically, the work stands apart from the rest of the prints of “The Congo,” all of which show the full bodies of Africans engaged in dance, war cries, or drumming. Instead, it more closely resembles other works such as African Phantasy and Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice. When considered together with these other works made during the same period, Untitled (Twin Heads) can then be understood as the singular work within the prints made for “The Congo” that countered the message in Lindsay’s poem; rather than supporting the rhetoric that framed Africa’s past as primitive, Untitled (Twin Heads) subtly communicates the artist’s belief in a utopic African past.

If this is the case, Wells’s illustrative prints can be understood neither as fully corrective of Lindsay nor as wholly in support of him, but rather as oscillating between the two attitudes. Instead of standing as anomalies in the artist’s oeuvre, Wells’s “Congo” prints instead become works in which, when contextualized within his other contemporaneous works and intellectual dialogues, the artist negotiated between the dominant visions of Africa during this period. Indeed, Wells demonstrates that, while seemingly contradictory, the ideas of an African utopic past and contemporary primitivity were not necessarily mutually exclusive, and ultimately evidences the heterogeneity of racial discourses being articulated in Harlem Renaissance during the 1920s and 1930s.

Figure 9: James Lesesne Wells, Twin Heads, c. 1929, Woodcut on thin laid Japan paper. 3 3/4 x 3 inches (block); 6 9/16 x 6 3/8 inches (sheet). Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Jakob Rosenberg Fund, George R. Nutter Fund, Gray Collection of Engravings Fund, and Margaret Fisher Fund

Endnotes

[1] Nicholas Vachel Lindsay, “The Congo: A Study of the Negro Race,” The Golden Book Magazine 10, no. 57 (Sept. 1929): 48.

[2] Lindsay, 50.

[3] While Wells also saw African art from the Blondiau Collection, this was not until after he left New York in 1930 to teach at Howard University alongside Alain Locke. He noted the singular significance of the Brooklyn Museum’s African art collection as the source of his early inspiration in developing his own artistic aesthetic in a 1986 interview (Richard Powell and Jock Reynolds, oral history interview with James Lesesne Wells, Nov. 16, 1989. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-james-lesesne-wells-11464). See also Dewey F. Mosby and Jane Seney, Life Impressions: 20th-Century African American Prints from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Hamilton: Picker Art Gallery, Colgate University, 2001), 39.

[4] The illustration appears in The Crisis 34 (Nov. 1928): 366.

[5] Willis Richardson, Plays and Pageants from the Life of the Negro (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1930).

[6] Powell and Reynolds, oral history interview.

[7] W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Looking Glass,” The Crisis 12, no. 4 (Aug. 1916): 182.

[8] Joel Spingarn, “Editorial: A Letter and An Answer,” The Crisis 13, no. 3 (Jan. 1917): 114.

[9] Eleanor Ruggles, The West-Going Heart: A Life of Vachel Lindsay (New York: Norton, 1959), 215.

[10] Susan Gubar, Racechanges: White Skin, Black Face in American Culture (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press), 141.

[11] Rachel Blau DuPlessis, “ ‘HOO, HOO, HOO’: Some Episodes in the Construction of Modern Whiteness,” American Literature 67, no. 4 (Dec. 1995): 675.

[12] Nicholas Vachel Lindsay, “Editorial: A Letter and An Answer,” The Crisis 13, no. 3 (Jan. 1917): 113.

[13] Lindsay’s first New York performance of “The Congo” took place in early 1916. While there is no record of whether Du Bois attended any of these performances, his subsequent change in opinion regarding the poem suggests that he saw Lindsay perform the work when the poet finally arrived in New York after touring the work for almost two years.

[14] W. E. B. Du Bois, “A Poem on the Negro,” The Crisis 10, no. 1 (May 1915): 18.

[15] Caroline Goeser, “ ‘To Smile Satirically’: On Wearing the Minstrel Mask,” in Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Identity (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2007), 279.

[16] W. E. B. Du Bois, “The African Roots of War,” The Atlantic 5 (May 1915): 11.

[17] Jeannette Eileen Jones, “Brightest Africa in the New Negro Imagination,” in Escape from Newe York: The New Negro Renaissance Beyond Harlem, ed. Davarian L. Baldwin and Minkah Makalani (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 43. See also John Cullen Gruesser, Black on Black: Twentieth-Century African American Writing About Africa (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000), 21.

[18] Paul H. Gray, “Performance and the Bardic Ambition of Vachel Lindsay,” Text and Performance Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1989): 221.

[19] Ira Dworkin has argued that Johnson’s song did not support the primitivizing imagining of indigenous Africa. Instead, he contends, the song was radical in its insinuation that blacks and whites experience romantic love in the same way, and in its ultimate emphasis on the similarities between the African, Parisian, and New York women featured in it. While Dworkin suggests that the song engaged in more complex social criticism than a simple rehashing of primitivist tropes of Africa, he does not consider how the song, by creating Umbagooda as a site in the Congo, still imagined indigenous Africa as a primitive place.

[20] Gray, “Performance and the Bardic Ambition,” 222.

[21] James L. Wells, James L. Wells: Retrospective of Prints and Paintings (Washington, D.C.: Howard University, 1977), 7.

[22] Lindsay, “Congo,” 48.

[23] Lindsay, 281.

[24] Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, vol. 5, 1905–1930 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968), 118.

[25] Powell and Reynolds, oral history interview.

[26] Richard J. Powell, “Talking with James Lesesne Wells,” Print Review 9 (1979): 74.

[27] Iris Schmeisser, “ ‘Ethiopia Shall Soon Stretch Forth Her Hands’: Ethiopianism, Egyptomania, and the Arts of the Harlem Renaissance,” in African Diasporas in the New and Old Worlds: Consciousness and Imagination, ed. Genevieve Fabre and Klaus Benesch (New York: Rodopi, 2004), 273.

[28] Schmeisser, 264.

[29] James Quirin, “W. E. B. Du Bois, Ethiopianism and Ethiopia, 1890–1955,” International Journal of Ethiopian Studies 5, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2010–11): 2.

[30] William Scott, “The Ethiopian Ethos in African American Thought,” International Journal of Ethiopian Studies 1, no. 2 (Winter/Spring 2004): 41.

[31] Iris Schmeisser, “Ethiopianism, Egyptomania,” 270. See also Stephen Howe, Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes (London and New York: Verso, 1998), 32.

[32] Schmeisser, 274.

[33] Schmeisser, 263.

[34] W. E. B. Du Bois, “The People of Peoples and Their Gifts to Men,” The Crisis 6, no. 7 (Nov. 1913): 339–341. The play was originally titled “The People of Peoples and Their Gifts to Men,” but is most commonly known by its later title, “The Star of Ethiopia.”

[35] W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Star of Ethiopia” (1914), 1. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

[36] Du Bois, 3.

[37] J. E. Caseley-Hayford, Ethiopia Unbound: Studies in Race Emancipation (London: Frank Cass, 1969), 167.

[38] Iris Schmeisser, “Ethiopianism, Egyptomania,” 270.

[39] Schmeisser, 273.

[40] Powell, “Talking with James Lesesne Wells,” 67–68.

Author Bio:

Ximena Kilroe is an MA student at City College focusing on modern art in Africa and its diaspora. She currently works as a curatorial assistant at the American Federation of Arts and is writing her master’s thesis on the Mozambican artist Bertina Lopes.