An Tairan

Princeton University

Abstract

Imagine a sixteenth-century foreign visitor to the Vatican being ushered into the Stanza di Eliodoro, frescoed and redecorated by Raphael and his workshop in 1511–14. How would she orient herself in this room of hyper dynamism, complex temporality, and hybrid geography? In this paper, I invite both the fictional early modern visitor and the reader to follow the indications of the frescoes themselves, as I unfold an interpretation of the movements, rotations, and turns that unite this room.

The visitor to the room is meant to be whirled around by it, as the four murals in the Stanza di Eliodoro, in my argument, are far from four static and separate scenes, but pictures in which figures and ideas move around with their drastic theatricality and fluidity. Featuring the Pope and his retinue as unfettered travelers in both space and time, the room is nothing less than an apparatus of “turning,” of (re)orientation and conversion: it virtually turns the visitors—both inside and outside the walls—towards the Temple in Jerusalem.

![]()

Four Observations on Orientation & Conversion: A Fictional Visit to Raphael’s Stanza di Eliodoro

1.

Picture a scene in mind: a sixteenth-century foreign visitor to the Eternal City (let us posit, a foreign ambassador of a diplomatic corps) coming after a long trek, probably from the east, steps into the Stanza di Eliodoro—second of the four Raphael Rooms on the third floor of the Apostolic Palace, famously redecorated by Raphael and his assistants in the early 1510s as a papal audience chamber—from its eastern entry, after passing through the easternmost Sala di Costantino, presenting herself before the Pope.[i] Upon entering the room, she immediately sees the fresco of the west wall, which, too, exhibits a meeting between a pope and a foreign, eastern visitor (fig. 1). Historically known as The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila, the west wall fresco depicts the historic parley between Pope Leo I and Attila the Hun in A.D. 452, in Mincio, near Mantua in the Lombardy region of northern Italy. This fresco was the last to be finished among the four in 1514, by which time the original patron Pope Julius II had died and it was his successor Pope Leo X who was shown instead in the picture, raising his hand to repulse Attila the invader. In other words, this fresco—a compelling mural image that immediately dominates the vision of the west-facing visitor—refers to the purpose of the room in quite an explicit way. In a sense the fresco draws the architectural space of the room into the pictorial field of the mural by absorbing, as it were, the actual event of the papal audience onto the surface, flattening the room against the wall. She who enters the room is almost at once drawn into the depth of time, as if she is reenacting a homologous event of the past. A papal audience, therefore, inhabits two temporalities—the actual present and the pictorial past—at one time.

Fig. 1 Raphael, The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila, Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

On the threshold of the two temporalities at play is the gaze of Attila’s warhorse: among the more than thirty human figures and fourteen horses depicted in the fresco, the black steed of Attila, precisely positioned at the very center of the picture, is the only one that is exchanging eye contact with the beholder of the fresco. Amidst hyper chaos and turmoil, the horse seems surprisingly aloof and detached, looking placidly toward us (fig. 2). The other figures are very much in character, so to speak, playing their roles: sitting calmly on a white palfrey, in white clothing, gold cape, and triple crown, is the Pope, while facing him, in contorted agitation, Attila looks skyward at the menacing apparitions of St. Peter and St. Paul; the papal group, cardinals, priests, and attendants are at rest and confident when the Huns and their horses, alarmed by Attila’s sudden, odd behavior, are astounded in twisting movements. In contrast to the immersive theatricality of the whole scene, this central figure, Attila’s dark, gallant battle steed turns itself towards the beholder, gently lifting its left hoof as if it is ready to stride over the confinement of the wall surface to enter the room. Perpendicular to the plane of the wall, its gaze straddles two temporal-spatial orders.

Fig. 2 Raphael, The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila (detail), Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

In the immediate vicinity of the outward-facing horse dwells an equally exceptional directionality (fig. 3). If we look up a bit above the horse’s face, another rather curious incident is detected: we see the side face of one of Attila’s horde, who does not turn away from the papal group and the miraculous appearance of Peter and Paul as most of the other cavalrymen alarmedly do, but decidedly leans his body towards the papal entourage, extending his arm with the hand open towards the uplifted hand of the Pope. Almost in perfect alignment with this arm, but in the opposite direction, are the backward-stretching arms of Attila himself, in the Hun ruler’s drastically consorted posture. To the left of the central figures, on the eye level of Attila, who wears a crown instead of a helmet, and the forward-leaning cavalryman, a soldier holds an ornate helmet in his hand. The center of the fresco is therefore being torn apart by two forces, as it were, in opposite directions: to the left, the outstretched hand towards the Pope and the removed helmet; to the right, the recoiling arms and the displaced, helmetless head of Attila. In the middle, the black horse turns its body to step towards us, the viewers in the actual space of the room, as if the horse is to be released to get out of the wall only when a gash is opened up by the unresolvable tension. Three, instead of two, centrifugal forces are rending the very center of the picture: the leftward, the rightward, and the outward.

Fig. 3 Raphael, The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila (detail), Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

Fig. 4 Raphael, The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila (detail), Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

The removed helmet, held up by a hand, is everything but ordinary: a military costume on display, a disjunct signifier without a signified, a dismantled mark of authority and power. Whose helmet is it? Does it belong to Attila, who is not wearing a helmet? Why is it removed and why is it exhibited like a piece of war booty by one of Attila’s own soldiers? On the right of Attila, the trumpeters amongst the thwarted barbarian warriors appear as strange and ill-timed as the helmet bearer: completely uninterrupted by the sudden riot, the players of the long trumpets act as if they are on a triumphal parade in celebration of a military victory (fig. 4). Indeed, if these musicians are compared with those in Andrea Mantegna’s Triumphs of Caesar, the connection between them is hard to deny. This series of highly acclaimed large paintings were created by Mantegna from 1485–95 for Francesco II Gonzaga, ruler of Mantua, representing the celebration of the victory of Julius Caesar in the Gallic Wars, a train of foreign military campaigns waged by the Roman proconsul against several Gallic tribes that resulted in the expansion of the Roman Republic over the whole of Gaul (see figs. 4 and 5; let us not forget that Leo I and Attila met near Mantua; one should also be reminded that Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici, who was shown the canvases of the Triumphs in Mantua in 1494, would later become Pope Leo X).[ii] Mantegna’s series of works showcase trumpeters leading the procession and wagons laden with spoils and booties captured by the Roman troops, along with a mass of trophies on spears, helmets and armor, headgear of all kinds (fig. 6).[iii] John Shearman suggests that Raphael traveled to Mantua in 1505 for the purpose of painting the portrait of the young Eleonora Gonzaga, daughter of Francesco II Gonzaga and Isabella d’Este.[iv] It is very unlikely, we may infer, that Raphael did not see Mantegna’s Triumphs himself during his Mantuan sojourn; even if he had not seen the original, Raphael would in all likelihood have known it well by the 1510s as Mantegna’s trophy of arms soon became enormously influential in print form and was copied into a range of media. [v] One could claim that in the production of the Attila fresco, Raphael very probably took inspiration from, if not directly quoted, Mantegna’s depictions of the Roman triumph.

Fig. 5 Andrea Mantegna, Triumph of Caesar, scene 1 (detail), London, Hampton Court Palace.

Fig. 6 Andrea Mantegna, Triumph of Caesar, scene 6, London, Hampton Court Palace.

What does it mean to include overt references to scenarios of triumphal procession and trophy display—puzzlingly enough, performed by members of Attila’s horde—into this fresco? The word “trophy” comes from the Greek noun trópos, “a turn, a direction, a way,” derived from the verb trépō, “I turn,” which is associated with the Latin torqueo, “to twist, to wrench,” and the Sanskrit traku, “spindle,” suggesting an Indo-European root associating the word with turning and twisting. The trophy is thus not so much an object of pompous demonstration of power, but rather a marker of a turning point on the battlefield (where the losing phalanx of enemy begins to turn), a force that contorts, a “trope” that turns the enemy around, a countermovement of directionality.

To turn the invader away from Rome was pretty much what Leo the Great achieved: as the result of the historic negotiations between Leo and Attila, the Hun ruler withdrew. Yet in Raphael’s artistic reenactment of the event, the “turn” is rendered in a much more complex fashion, given the fact that the trophy is presented by Attila’s own warrior, as a token of victory prior to any victory. As mentioned above, while Attila is emphatically turned away from the papal group, the cavalryman next to him is, on the contrary, turned towards the Pope. In this regard, the trophy helmet marks not one “turn,” but two, in their opposite directions.

It is hard to ignore the garishly decorated helmet of this central figure (fig. 7). The exceedingly long, reddish feathers on the helmet is anything but usual. One art historian goes so far as to identify this person as “the first expression of the Church’s idea about the Indian in a monumental decorative cycle” ever since Columbus’s landing in San Salvador Island on October 12, 1492, as “he wears an American Indian feather bonnet over his helmet,” and asserts that “[b]y gesturing towards the pope, the (American) figure wearing a feather bonnet demonstrates his receptivity to divine grace at the very moment when his European companions reject it.”[vi] In other words, according to this interpretation, by grafting an American Indian war bonnet onto a Hun soldier’s helmet, Raphael alluded to Christianity’s conversion of the New World. This might be too bold a claim since in the Amerasian imaginary of early cinquecento, an American feature like this could very possibly be appropriated to signify a very far eastern Eurasian geography (the Huns—long believed to be associated with the “Scythians,” a term that the Europeans had used for long to refer to all nomads of the Eurasian Steppe—are indeed uninvited visitors coming from an eastern geography that is very far away).[vii] Yet what is interesting for us in terms of this American Indian association, as we grapple with issues concerning the “turn,” is the notion of conversion. Is not “conversion,” if we have recourse to etymology one more time, an enterprise of “turning”? The Latin verb converto, from which the word “convert” is derived, means “to turn, to rotate.” One could argue that in his “turning-towards” the papal entourage, the feathered person at the very center of the picture is being converted to the Church.

Fig. 7 Raphael, The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila (detail), Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

In the middle of the two contradicting turning forces, the black horse, by twisting its body posture, turns outwards—staring at us, about to step into the room—towards the actual east. Attila’s name, as a number of scholars have suggested, very probably has a Turkish/Hunnic/Mongolian origin associated with “gelding, steed, or groom.”[viii] Perhaps, as the etymological link between Attila’s name (is not a name a tropological—dare I say, turning—device in and of itself?) and the horse suggests, one could not separate the three forces, or the three “turns” that are set in motion by the artist, just as one could not isolate this fresco from the ones on the other three walls. The Stanza di Eliodoro as a whole could also be read as both a turning apparatus and an apparatus of the “turn,” as the following sections try to demonstrate.

2.

Let us invite our visiting ambassador to turn her body around, following the gaze of Attila’s steed, and look up at the mural of the east wall, The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, after which the room was named (fig. 8). Painted by Raphael for Julius II from 1511–13, it was the first of the four murals of the room to be finished. The “Temple” in the title of the fresco refers to the Temple in Jerusalem; in other words, the ambassador, a foreign visitor from the east, is looking at an oriented fresco on the east wall of the room, depicting an oriental biblical event that happened in the Temple in Jerusalem in the remote past—of the four events depicted on the four walls, the expulsion of Heliodorus is at the same time the most ancient and the farthest away. The fresco, therefore, intends to stride over a huge distance that is both geographical and temporal.

Fig. 8 Raphael, The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

The biblical episode is recorded in the second book of Maccabees: around 178 B.C., Seleucus IV Philopator, King of Syria, sent his minister Heliodorus, the protagonist of the fresco, to seize the treasure preserved in the Temple in Jerusalem. Even after learning from Onias, the high priest of the Temple, that some of this money was destined for widows and orphans, Heliodorus announced that he would still follow the royal orders. Answering the prayers of Onias, it was God who sent a horseman assisted by two youths armed with whips to drive Heliodorus out. One could point out a lot about what the Attila fresco and the Heliodorus fresco have in common: both events are about protecting the Church from the looting of foreign invaders; both call forth divine interventions; both have a papal retinue on the left, in which the patronal pope is anachronistically included into the historical scene, and the thwarted plunderers on the right.

Yet one has to be more careful here: in the two frescoes, the ways in which contemporary figures are inserted into the picture differ vastly with one another. Unlike Leo X in his portrayal of Leo I in the Attila fresco, who is very much in character playing his part as the defender against Attila, in the Heliodorus fresco, Julius II and his entourage appear rather detached from the whole scene (fig. 9). As Michael Schwartz points out, the contemporary figures in the fresco—a papal retinue of three people, with Julius II borne on the sedia gestatoria—are differentiated from the historical ones in multiple ways: first, the clothing of the papal group is accurately modern, that of the historical figures less so; second, the contemporaries are relatively inactive and stationary, in contrast to the far more animated and dramatic historical characters; third, the colors used for the historical figures are paler, with more whitish highlights, while the contemporary figures have stronger colors, bolder and fuller reliefs, rendering these four contemporary people at the far left corner spatially nearer to the beholders, as if they convey a greater sense of immediacy.[ix] Following Schwartz, one may argue that in its observable contrast to the geographical and temporal remoteness of the historical dramas, the papal group here resembles little of the papal group of the Attila fresco, but is very much like Attila’s black steed: they stand on the threshold between the actual room and the pictorial surface, between the here and the distant oriental Holy Land, between the now and the remote biblical past. They are in and out of the picture at the same time, disengaged from the historicity of the very event, inhabiting two configurations of space and time at once—are the two litter-bearers not the only figures in this fresco to exchange eye contacts with the beholders, just like Attila’s horse?—let alone the fact that the papal attendant to the far left is literally stepping onto the threshold between the pictorial and the actual: he is getting a foot in the door, so to speak, as there is a real door lintel below him. While the other figures are decidedly immersed in the historical actions, the Pope and his retinue float adrift, unanchored, refusing to play roles in the drama; they seem to be nothing more than a group of aloof, untimely spectators, strolling idly into the furioso of the historical theatre. Concerning the incongruity, untimeliness, and movement of the papal group, Deoclecio Redig de Campos offers a convincing paragraph that hits on the same idea:

“These ‘dramatis personae’ do not take part in the play; they stand outside the stage and have as little or as much to do with the event being portrayed as we do. Yes, that is right; but that is exactly what Raphael meant and wanted! The Pope and his entourage do not belong to the history of Heliodorus. They are not in the fresco like the other figures, although they walk on the same floor: they pass him. The painting is a “picture in the picture” and its real title would be: “Julius II watches the expulsion of Heliodorus.”[x]

Fig. 9 Raphael, The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (detail), Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

Viewed as a group of spectators walking outside history, the Roman pontiff and his courtiers are not so much anachronistic insertions into the picture as free-flowing time travelers.[xi] They seem to have just entered the picture from the left edge, moving rightwards on the mural surface.

What exactly, one may ask, is such a movement? Where is the Pope moving towards, and where is he moving from? In light of the ambiguous conditions of the papal group, as we have identified, to begin to answer these questions would mean to complicate them. If they are in and out of the picture at the same time, they would have to take up two sets of directionality, two structures of orientation, and two orders of temporalities: that of the pictorial and that of the actual.

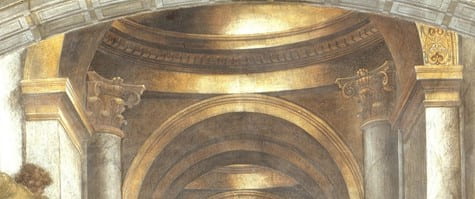

One point of departure might be to contemplate a bizarre architectural detail that could possibly imply an interpretation of pictorial directionality: the damascene pattern on the arch of the temple, which is an “oriental” feature, appears only on the right-hand side (fig. 10). Why is there such an inconspicuous yet absolute asymmetry in the decoration of the architectural setting? John Shearman believes that Raphael “forgot” to paint the other side.[xii] I would rather believe in the artistic rigor of Raphael and his workshop and take this discrepancy seriously. Could this unexpected pictorial interposition—a signifier of difference, a reminder of imbalance, a trope that “turns,” a disturbance, an accident—be a marker of orientation and movement? The chiaroscuro modeling of the figures, the light and shadow on the surface of the golden domes, as well as the consistent direction of cast shadows indicate that the whole scene share a common source of illumination that comes from the right-hand side. The association of light with divinity is as old as religion, which is affirmed by a clear left-to-right directionality in the spectatorship of the oriental event in the foreground, corresponding to the orientation of the High Priest in the middle. The High Priest, the communicator of God, on his knees facing the Ark of Covenant on the right, seems to be looking up over the Ark of Covenant, along the lit-up parts of the golden domes, at something beyond the picture plane, that is—we have to invite our visiting ambassador to raise her head—God himself, on the ceiling fresco of the east wall (fig. 11).[xiii]

Fig. 10 Raphael, The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (detail), Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

Fig. 11 Raphael, The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (ceiling fresco), Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

Raphael’s east ceiling decoration illustrates an episode from the Old Testament: Moses before the burning bush. In the biblical narrative, the burning bush is the location at which Moses was appointed by God to lead the Israelites out of Egypt into Canaan. In other words, Moses, now in Egypt, received God’s divine message to go east. In this ceiling fresco, God emerges, again, from the right, orienting Moses with his divine power. At this point it is reasonable to claim that, in the fresco, the right-hand side is the east. One could further corroborate the claim on orientation by pointing to the fact that it is exactly Moses—the receiver of divine message—that is represented on the keystone of the semicircular arch of east wall. If right is east in the picture, then the papal group, who seems to have just arrived at the scene from the very left, is marching east just like Moses, towards the Temple in Jerusalem.

Yet their strong sense of immediacy and detachment, their temporal and spatial proximity, and their eye contact with beholders indicate that they might also share with us the orientation of the actual world: in the actual orientation, the papal group enters the theatre of history, so to speak, from the north. Some biographical information of Julius II, as many scholars have introduced, might be noteworthy here: it turns out that in the year of 1511, on June 27, right before the inception of this fresco, Julius II returned Rome from north Italy after being defeated by Louis XII of France. The fresco takes its subject to underline the integrity of the papacy’s spiritual and actual revenues, the stability, security and authority of the Sancta Romana Ecclesia, which are to be defended against avaricious princes. That Heliodorus is cited as an exemplar of avarice, and the Expulsion of Heliodorus is an allegory of the protection of God over the treasury of the Church, an admonition against the foreign cities and the banishment of avarice (the French king went so far as to prohibit church taxes in France), has been explained by Shearman and many others.[xiv]

Instead of recapitulating a well-established allegorical interpretation to read the fresco as a metaphor of papal protection on fiscal and territorial integrity of the Church, I offer an interpretation from a different angle: not by resorting to biographical information and external historical evidences—although they are undoubtedly crucial—but by staying inside the room, in which the actual north, from which direction the Pope enters the east wall mural, directs our attention to the north wall: The Liberation of Saint Peter (fig. 12). It is not controversial that the unchained St. Peter has a specific association with Julius II as for thirty-two years Julius had been cardinal in San Pietro in Vincoli (“St. Peter in Chains”; he was later buried there, too), which is the Roman church that venerates exactly this specific biblical episode, and it was a common practice to call the cardinal by the name of his titular church. Frederick Hartt offers an example of this rhetorical convention: in a letter written to Gianfrancesco II Gonzaga in 1503 by the Mantuan ambassador Ghiviziano, he said “S. Pietro in Vinculi has been proclaimed as Pope Julius II.”[xv] One could argue that with the help of the tropological function of the names (of the saint, of the church, of the cardinal, and of the Pope), Julius II is the liberated St. Peter; the Pope “enters” the left hand corner of the east wall, after, as it were, being freed from the containment and, literally, the immurement of the north wall (fig. 13). With the help of the Archangel, St. Peter/Julius II is taking a few steps down the stairs towards us in the actual space, about to exit the prison, or to exit the north wall; he would subsequently turn his body around the corner and step over into the east wall.

Fig. 12 Raphael, The Liberation of St. Peter, Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

Fig. 13 Raphael, the corner between The Liberation of Saint Peter and The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

One needs to be reminded of the fact that the four corners were crucial parts to Raphael’s redesign of the whole room: under Raphael’s scheme, the four corners were extended downwards (as those of the Stanza della Segnatura had been) to make a consistent but fictive structural system with full semicircular arches framing each event.[xvi] In so doing Raphael linked the neighboring frescoes with an architectural joint—a turning point in and of itself—by alluding to the problem of “turning the corner,” one of the most persistent and quintessential issues in classical architecture which had recently been taken up (famously by Brunelleschi, Alberti, Giuliano da Sangallo, Bramante, and Raphael himself, among numerous other Renaissance architects). The corner of the room is therefore not only an architectural element that literally turns, but also a tropological device of turning: from The Liberation of Saint Peter on the north wall to The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple on the east wall, by turning around the corner, St. Peter “turns” into Julius II, and the actual orientation of the room “turns” into the pictorial orientation of the fresco. Released by God from the containment the north wall, Julius II “turns” into the Heliodorus fresco to receive divine messages (is not the Pope gazing at the High Priest, the messenger of God?), facing east, towards the Temple in Jerusalem.

3.

I hope by this point, both our visiting ambassador and the reader of this essay have been convinced that the four murals in the Stanza di Eliodoro are not four static and separate scenes, but pictures in which figures and ideas move around with their drastic theatricality and fluidity—as we invite the ambassador to turn towards the last wall of the room, the south wall, and see The Mass of Bolsena (fig. 14). It depicts a Eucharistic miracle that happened in the year of 1263 in the town of Bolsena, in central Italy in the Lazio region, not very far from Rome. The story is about a Bohemian priest who ceased to doubt the doctrine of Transubstantiation when he saw the bread of the eucharist began to bleed. Here, too, we see Pope Julius II himself, with four prelates behind him and five Swiss guards in the foreground, kneeling on the right of the altar. Here almost exactly the same could be said about the Pope and his entourage as in The Expulsion of Heliodorus: the contemporary figures wear distinctly magnificent dresses, in sharp contrast with the more generic draperies of the figures in the left foreground; they are less dramatic, more inactive and calm; again, they are charged with stronger colors and fuller reliefs, explicitly casting shadows, as if they are closer to the beholder both spatially and temporally. Again, they are the threshold figures between here and there, past and present; they are indifferent spectators of the dramatic event, in and out of the picture at the same time, etc. It is no coincidence that among the Swiss guards, one person looks out of the picture with a clear gaze into the beholder in the actual room. We might postulate that on the east, south, and north walls, where Julius II was either included in the picture or represented as St. Peter, the Pope always seems to be a free agent, unbounded by the mural, as if he is ready to move around between the walls.

Fig. 14 Raphael, The Mass of Bolsena, Vatican City, Vatican Palace, Stanza di Eliodoro.

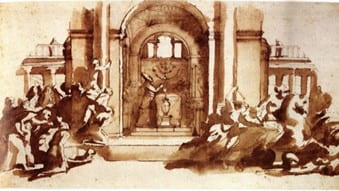

However, this “principle of free movement,” so to speak, is not pronounced in The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila, where the new Pope actively takes up his role as the defender against Attila. An earlier study drawing of this fresco might represent Raphael’s preferred design (fig. 15). This drawing records a different composition: the flying saints Peter and Paul now play a primary rather than a secondary role. It is the divine intervention on the Pope’s behalf, but not the pontiff himself, that halts the invading army. The resulting turmoil now fills up the entire foreground of the design from one side to another. “The most startling invention of all,” to quote Shearman and John White, “is in the placing of the other protagonist in the human embodiment of the drama. Leo and his retinue are now all but invisible.”[xvii] The papal group is diminished to a mere speck in the distant landscape, almost indistinguishable (fig. 15). Similar to what we have seen in The Expulsion of Heliodorus and The Mass of Bolsena, the pope and his entourage are merely onlookers of the historical event. In all three cases, the sense of detachment is emphasized by a delicate treatment of spatial depth: in the previous two, the contemporary figures are subtly drawn closer to the beholder; in this study drawing of the Attila fresco, however, they are emphatically pushed deep inside. In all cases, including The Liberation of Saint Peter, the Pope (or, St. Peter in the case of the north wall fresco) is not embedded into the actions of the historical drama, but is like a free-flowing traveler that resists anchoring to any specific place and time.

Fig. 15 By or after Raphael, Modello of a Project for The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila, Paris, c. 1513, Musée du Louvre.

Fig. 15 By or after Raphael, Modello of a Project for The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila (detail), Paris, c. 1513, Musée du Louvre.

Two more early study drawings illustrate a similar idea, but in different ways. In a study drawing of The Expulsion of Heliodorus (fig. 16), the modern intrusion of the pontiff is yet to happen. One of the more striking contrasts between the drawing and the fresco is just how shallow the space in the modello is, as if the arrival of the Pope would push the historical event into the depth of the wall. In another study drawing of The Mass at Bolsena (fig. 17), again, the space of the modello is significantly shallower than that of the fresco: in the drawing the pope has arrived at the scene, but not fully in his position, as if he is ascending the stairs to approach the altar, and as he steps up towards the miracle, the whole event is pushed deeper into the background.

Fig. 16 After Raphael, Modello of a Project for The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple

Fig. 17 After Raphael, Modello of a Project for The Mass at Bolsena.

The Pope always seems to arrive late, and when he arrives as a latecomer, history is either pushed back inside, or pulled forward as we see in the modello for the Attila fresco. In other words, history is always estranged, distanced, contrasted, and dramatized. But even as a late arriver, the Pope never misses anything, as if the historical actors are motionless and static sculptures, awaiting the papal gaze. In their hyper-theatricality and dynamism, the historical scenes are staged as a tableau vivant. The Pope, on the other hand, readily moves around the room, travels through time and distance. But where is he traveling to?

The four frescoes of the room illustrate four events about heavenly protection granted by God to the Church, two biblical and two post-biblical, leaping over a history of more than a thousand years, straddle a vast geography from central Italy to Jerusalem: The Expulsion happened in the year of 178 B.C. in the Temple in Jerusalem; The Liberation of Saint Peter in the year of A.D. 44 in a prison near Jerusalem; The Meeting of Leo I and Attila took place in A.D. 452 near Mantua; The Mass of Bolsena stages a miracle of 1263 in the town of Bolsena, in central Italy. I do not intend to place the four events into a chronologized sequence, even if they do seem to fall into a chronological order if one starts with the most ancient Expulsion of Heliodorus, in a counter-clockwise direction, and ends with The Mass of Bolsena—after all, the second decade of the sixteenth century was long before the modern conception of linear chronology would take over. Instead, one might revisit the “turning corner” of the room and turn to the biblical episode of The Liberation of Saint Peter to seek a possible answer: it was Herod Agrippa, King of Judea, in the year of A.D. 44, that put Peter into prison. We do not know where exactly Peter was incarcerated and liberated, probably somewhere near Jerusalem, but we do know that he was rescued by the angel during the Passover festival. According to the biblical account, he was put in prison right before the Passover of that year, and King Herod intended to put him to death publicly after Passover. That the rescue happened during Passover is significant as it delivers a geographical and directional message: before the destruction of the Second Temple (A.D. 70), Passover was a pilgrimage festival during which all people would make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem.

Is not the Pope on his pilgrimage as well? Perhaps the four events should be read in a clockwise direction from south to west to north to east, in which the pope geographically travels from Rome all the way to the Temple in Jerusalem, and temporally travels backward, passing through the events into the abyss of biblical time. On his imaginary pilgrimage, after all the turns, twists, and re-orientations, the Pope finally emerges from the left-hand side of The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, arriving at the temple after a long journey towards the east, yet to occupy the empty center.

4.

At this point, our visitor notices that Attila’s steed, with its twisted, outward gesture in the very center of the Attila fresco, is turning its body to gaze at the nave of the Temple in Jerusalem on the east wall. As a trope of Attila, the horse is converted—that is, turned—to orient itself towards the Temple (there is indeed a divine horse—“converted” from black to white—in The Expulsion of Heliodorus). The miracle of Bolsena is certainly a story of conversion, but is it not the case that both Attila and Heliodorus, the two foreign invaders, are being turned around, twisted, rotated, and finally, converted? It is no wonder, as Paolo Alei points out, that in Raphael’s entire oeuvre the most similar representation to The Expulsion of Heliodorus is The Conversion of St. Paul, a cartoon by Raphael and the tapestry made from it in the Sistine Chapel (fig. 18).[xviii] For a sixteenth-century visitor like our foreign ambassador, the room is nothing less than an apparatus of “turning,” of orientation and conversion. It turns the unbelievers towards the virtual Temple in Jerusalem, yet the virtual Jerusalem, arguably, is here in Rome.

Fig. 18 Raphael, The Conversion of Saint Paul, Vatican City, Vatican Museums.

Acknowledgment: The author would like to thank Professor Alexander Nagel for his patient guidance and generous support as the paper took shape, both during and long after his Fall 2019 seminar “Orientations of Renaissance Art” at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU for which the paper was originally written.

Endnotes

[i] On the Stanze di Eliodoro as a papal audience chamber, see: John Shearman, “The Vatican Stanze: Functions and Decoration,” Proceedings of the British Academy, LVII (1971): 383. In terms of the orientation of ceremonies and audiences, see: John Shearman, “The Expulsion of Heliodorus,” in Raffaello a Roma: il convegno del 1983 (Roma: Edizioni dell’Elefante, 1986), 75–76. Shearman states that “Ceremonial conventions would place the papal throne most naturally against the opposite wall, under the Repulse of Attila and facing the Expulsion of Heliodorus.” For this reason, these two frescoes are given special emphasis and significance, both historically and in this essay.

[ii] See: Paul Kristeller, Andrea Mantegna (London: Longmans, Green and Company, 1901), 279. On March 2, 1494, Isabella d’Este proudly showed the canvases of the Triumphs to Giovanni de’Medici. Copperplate engravings and woodcuts, as well as painted copies, quickly spread the reputation of this series of works. These works would later hang in a large hall in the Palazzo San Sebastiano (now the Museo Civico) in Mantua, then in 1627 they passed to the British Royal collection. I am grateful to Danarenae Donato who directed my attention to Mantegna’s Triumphs.

[iii] The powerful sound of the long trumpets, morphologically identical to the ancient Roman tubae present in both tubilustrium and triumphs, is a very popular motif in the triumphal entourage, where its presence contributes to emphasize the idea of triumph and pomp of the parade and, at the same time, proclaims the triumph of Caesar. See: María Isabel Rodríguez López, “Victory, Triumph and Fame as the Iconic Expressions of the Courtly Power,” Music in Art (2012): 9–23.

[iv] John Shearman, “Raphael at the Court of Urbino,” The Burlington Magazine 112 (February 1970): 72-78. On the connections between Raphael and Mantegna, see: Avraham Ronen, “Raphael and Mantegna,” Storia dell’arte 10 n 33 (1978): 129–33.

[v] On Mantegna himself as an engraver and printmaker, see: Keith Christiansen, “The Case for Mantegna as Printmaker,” The Burlington Magazine 135, no. 1086 (1993): 604–12; Leona E. Prasse, “The Engravings of Andrea Mantegna,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Vol. 43, No. 4 (Apr., 1956): 59–62. On the Triumphs being copied and engraved, see: Suzanne Boorsch, “‘The Elephants’ after Andrea Mantegna: An Engraving Drawn Over,” Master Drawings 31, no. 4 (1993): 368–76; Andrew Martindale, The Triumphs of Caesar by Andrea Mantegna in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Hampton Court (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 1979).

[vi] Charles Colbert, “‘They are Our Brothers’: Raphael and the American Indian,” The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Summer, 1985): 181–190. Colbert’s claims in this essay are not well-received. For example, the art historian Lia Markey discredits Colbert’s argument as “less convincing.” See: Lia Markey, Imagining the Americas in Medici Florence (University Park, PA: Penn State Press, 2016), 166. On Raphael’s studies of animals of the New World that had been brought to the papal court, see: André Chastel, “Masques mexicains à la Renaissance,” Arte de France 1 (1961): 299; see also: John O’Malley, “The Discovery of America and Reform Thought at the Papal Court in the Early Cinquecento,” in First Images of America: The Impact of the New World on the Old, Volume 1, ed. Fredi Chiappelli, Michael J. B. Allen, and Robert L. Benson (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 185–200.

[vii] For an in-depth account of the post-1492 Amerasian imaginary of early modern Europe, see: Elizabeth Horodowich and Alexander Nagel, “Amerasia: European Reflections of an Emergent World, 1492–ca. 1700,” Journal of Early Modern History 23.2-3 (2019): 257–95.

[viii] The etymology of Attila’s name is a very debatable issue. For some latest discussions, see: Hyun Jin Kim, The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2013); Magnús Snædal, “Attila,” Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia, 20.3 (2015): 211–19. For a more thorough linguistic survey, see also: Omeljan Pritsak, “The Hunnic Language of the Attila Clan,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies. VI (4) (1982): 428–76.

[ix] Michael Schwartz, “Raphael’s Authorship in the Expulsion of Heliodorus.” The Art Bulletin 79.3 (1997): 466–92.

[x] Deoclecio Redig de Campos, “Julius II. und Heliodor: Deutungsversuch eines angeblichen ‘Anachronismus’ Raphaels.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 26.H. 2 (1963): 168. My translation. Some art historians once regarded the incongruity of the papal group as a felix culpa of the masterpiece, which de Campos emphatically refuted.

[xi] One of de Campos’s conclusions in this very succinct essay is that the papal group is not an anachronism, but a group of spectators outside of the scene.

[xii] Shearman, “The Expulsion of Heliodorus,” 79–80.

[xiii] The one-to-one correspondence between the four major frescoes and the four ceiling paintings was part of Raphael’s design. In fact, the Stanza di Eliodoro was not merely pictorially redecorated by Raphael with his new murals, but also partially renovated architecturally. In terms of the ceiling, the original eight-rib central area was changed to a four-rib system, each diagonal rib now seeming to support fictive tapestries “woven” with scenes from the Old Testament, which act as retroactive tituli to the histories below. See: Shearman, “The Expulsion of Heliodorus,” 76; John Shearman, “Raphael’s Unexecuted Projects for the Stanze,” Walter Friedlaender zum 90. Geburstag, Berlin (1965), 173–74.

[xiv] Shearman, “The Expulsion of Heliodorus,” 82–84. See also Paolo Alei, “‘As if we were present at the event itself’: The Representation of Violence in Raphael and Titian’s Heroic Painting,” Artibus et Historiae 64 (2011): 221–42.

[xv] See: Frederick Hartt, “Lignum Vitae in Medio Paradisi: The Stanza d’Eliodoro and the Sistine Ceiling” The Art Bulletin (Jan 1, 1950), 118–19. The identification between Julius with St. Peter has been an agreed account and considered decisive by many others, from earlier scholars including Oskar Fischel and Ludwig von Pastor to more recent ones such as Helen S. Ettlinger. See: Helen S. Ettlinger, “Dominican Influences in the Stanza della Segnatura and the Stanza d’Eliodoro.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 46 (1983): 176–86.

[xvi] See note 13.

[xvii] John White and John Shearman, “Raphael’s Tapestries and Their Cartoons: II: The Frescoes in the Stanze and the Problem of Composition in the Tapestries and Cartoons,” The Art Bulletin 40.4 (1958): 306. See also: Roger Jones and Nicholas Penny, Raphael (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983), 118–21.

[xviii] Alei, “‘As if we were present at the event itself’: The Representation of Violence in Raphael and Titian’s Heroic Painting,” 233–34.

Author Bio:

An Tairan is a Ph.D. candidate in History and Theory of Architecture at Princeton University. Tairan holds a bachelor’s degree in Urban Planning from Peking University and an MDes in History and Philosophy of Design with distinction from Harvard GSD. As an architectural historian, Tairan is interested in the theoretical problems of mobility in time and space since the early modern period, and seeks to embrace the notion of temporal instability as a historiographical postulate. His ongoing dissertation project investigates how the unpredictability of natural processes and the stabilizing nature of architecture collided and coalesced in nineteenth-century Italy, where a series of anomalous encounters between architecture and this other force which we now call the environment were induced. His research has been supported by grants from the Canadian Centre for Architecture, the Lemmermann Foundation, the High Meadows Environmental Institute of Princeton University, as well as by a Harvard University Frederick Sheldon Traveling Fellowship.