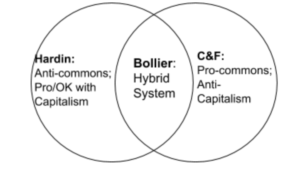

The readings for this week discuss the concept of the commons, and the implications of the misuse of common resources by individuals in various contexts. The classic 1968 text, “The Tragedy of the Commons”, by Garrett Hardin, discusses his belief that the issues caused by overpopulation of the earth cannot be solved by technology. According to Hardin, however, there is no agreeable solution to this problem, because as long as the downsides of individual actions do not exceed the individual positives of that action, there is no incentive to alter behavior. Hardin relates his explanation of the tragedy of the commons to many contemporary and historical examples. From pastures to parking spaces, the absence of rules incentivizes selfishness as the negative impact is externalized and therefore only a fraction of the positive impact. In “Commons Against and Beyond Capitalism”, by George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici, the arguments of Hardin are extended and adapted to apply to modern events, such as the current economic situation in Greece. Caffentzis and Federici argue that, in the absence of a functional capitalist economy, a commons-like collective of sharing emerges. The aid of “free medical services, free distributions of produce by farmers in urban centres, and the ‘reparation’ of the electrical wires disconnected” (Caffentzis and Federici), are examples of the mutual aid which comes to be in Greece. This is later equated to the squatters movement, to complete the argument that commoning and collective movements such as these come out of necessity, due to the dire situations that arise from capitalism. The extremes of the free market, therefore, often create a desire and need for a commons. Further, the concept of the commons, Caffentzis and Federici argue, is the basis for the more recent formation of what they refer to as “soft capitalism”, which they present as a solution to the extreme, neo-liberal capitalist practices, which often work counter to the best interests of the majority of people.

While this week’s readings offer some very interesting examples, applications, and interpretations of the principle of the commons, with numerous historical and contemporary applications, they are weak in their discussion of possible solutions to the tragedy of the commons. Hardin discusses the need for internalizing the external cost of actions against the good of the commons, which could work in a similar way to taxes. As Hardin points out, the only solution to the tragedy of the commons is to remove the benefits of exploitation, but this is exceedingly complicated. It is this dilemma that makes the commons, inherently tragic.