Elizabeth Blackmar’s Manhattan for Rent, Lawrence Veiller and Robert De Forest’s The Tenement House Problem, and Keith D. Revell’s Regulating the Landscape: Real Estate Values, City Planning and the 1916 Ordinance all provide a historical backdrop for how New York real estate has developed its structure and policies of today. As a real estate agent in the process of acquiring an investment property, these texts currently contextualize my actions in shaping the built environment, which, as the readings show, influences essential livelihoods. Through these excerpts, it is clear how multiparty, profit-driven control of private property can manipulate livelihoods for the worst. On the same token, public regulation of private property can either behoove the community or fall into the hands of private interests.

As the readings illustrate, private interests have always dominated Manhattan real estate. The tenements described in Forest’s The Tenement House Problem were produced by multiple parties- the Building Operator, speculative builder, and investor- who wanted to profit through high density, low cost housing. Likewise, the wealthy proprietors and rentiers described in Manhattan for Rent controlled swaths of land first to preserve wealth and secondly to create wealth. Even the tenants of the rentier’s land wanted to turn a profit and would do so by subleasing out part of their land. Additionally, in Regulating the Landscape, proprietors actively pressed for limits on the heights and size of buildings, simply to lessen supply and maintain their own property values. Oftentimes, these real estate interests sought profit regardless of the ill effects to others.

Tenement houses are a prime example of how private property interest can be detrimental to individual livelihoods. The multilevel operation added significant cost to building the house, as every party wanted to make a profit. This took away funds that could have been spent making an actually livable building. As touched on in The Tenement House Problem and Regulating the Landscape, poor building planning and not leaving enough space for air, can even lead to health problems like tuberculosis.

Additionally, as seen in Manhattan for Rent, control of land oftentimes translates to control of production and labor. With sky-high rents, laborers and artisans may be priced out of working in a market. This ties back to Lockean theory and Henry George, who influenced progressives of the time who rallied both for and against private property on the basis that gross accumulation of land is unethical, workers have a right to their labor, and rent takes away fruit of one’s labor. Private property was dubbed evil in that a scarce property market restricted another’s freedom to work. At the same time, private property was advocated as essential to the freedom to work itself and the right to claim the bearing of one’s work.

To alleviate some of these qualms, New York public policy, as described in Manhattan for Rent and Regulating the Landscape, sought to redistribute land by breaking up large tracts and to regulate current building structures while planning for the future. The former helped redistribute land to the middle class. The latter helped provide for more air circulation, sunlight, public space, and urban decongestion.

Despite these positive effects, public policy did not always protect community interest as it should. In the case of tenement houses, building regulation was weakly enforced. In the case of the 1916 Zoning Ordinance, corrupt interest swayed much of the public policy, as at least half of the CBDR board was connected to the real estate industry. This essentially gave real estate executives the power to guide public action based on their private needs, while the initial goal was the opposite: for public needs to guide private action. The 1916 Zoning Ordinance still offered public benefits of providing order to the congested city; it simply was not as impactful as it could have been as it failed to deconstruct a history of property manipulation by colonial elites and simply built upon it.

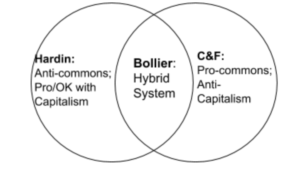

Without the pressuring hand of private industry, however, public intervention into private property may be an adequate way to manage a system of unequal capitalist real estate interests. However, just because the private real estate market is currently managed by public oversight and driven by individual interest, doesn’t mean it will always be this way. Across countries like the UK and US, some individuals attempt to shy away from capitalism through joining co-op communities, where large resources, such as land and housing, are collectively owned. Although these communities are dwarfed by the rest of capitalistic society, they represent the possibility of blending public and private interests even past the cooperation that was seen with the 1916 Zoning Ordinance and current management of property and land.