Amazonization drastically changed the western consumer desire and expectation. Amazonization is understood to be business improvement approaches as started by Amazon (Tadepalli). These improvements have created the giant that is Amazon and significantly changed e-commerce because consumers are now accustomed to the shopping experience Amazon has facilitated. This paper will discuss what were the “business improvement approaches” Amazon made, how it differs from 19th century consumer culture, and how it changed e-commerce. This leads into a discussion surrounding the impacts of amazonization on consumer desire. This phenomenon values efficiency and convenience for both the buyer and the seller. Amazon has created a website that attempts to eliminate any “friction” between the two parties (Tadepalli). Friction in this sense is understood to be any behavior or elements in the buyer-seller relationship that will discourage the buyer from purchasing the product (Tadepalli). This paper explores how the elimination of labor time from the buyer-seller relationship was necessary for the success of amazonization and deemed a source of “friction”. The negative effects of this will be discussed and how the amazonization of consumer desire has led to unethical business practices. In this paper the amazonization of consumer desire will be explored by comparing modern day consumer culture to 19th century shopping experience, the evolution of e-commerce and buyer’s expectations, as well as, the elimination of labor time from today’s buyer-seller relationships.

Amazonization was brought about by the e-commerce shopping website, Amazon, and dramatically changed online buyer-seller experiences. Amazon began as a bookseller website in 1995 (Schrager). Delivery took days to weeks, the market was small in comparison to today, and many were skeptical. Amazon quickly realized the opportunity in e-commerce and expanded its products in 1998, by 2000 the website opened up to third-party retailers (Schrager). “Amazon [sold] more than 12 million different products, from baby formula to rare coins. This meant it became easy to compare prices and products (and see reviews) in a way that was impossible in person” (Schrager). This was the beginning of amazonization. Amazon was developing website changes (aesthetically and technologically) so that their site would become more popular, people would choose it over other sites/in-person shopping, and exponentially grow in success and profits (Tadepalli). “In 2005 it launched Amazon Prime, which streamlined the ordering process, offered free delivery, and created more customer loyalty. It was during this period that buying goods online became a way of life” (Schrager). Through the creation of Amazon Prime, Amazon has fostered a consumer culture in which buyers come back much more quickly. The simplification and efficiency of the transactions and deliveries ensures a higher rate of customer loyalty. This customer loyalty is an effect of amazonization. The changes Amazon made to their business model encouraged this. Once consumers became accustomed to this way of shopping, their expectations were raised. This drastically changed e-commerce because Amazon’s competitors had to compete to stay in the market, so other online stores began to “amazonize” by streamlining ordering processes, lowering delivery fees, and encouraging customer loyalty.

Amazon has been one of the major players in popularizing e-commerce. Since Amazon expanded their product range on their site, their prevalence has sky-rocketed. Their success brought about a new age of shopping. “According to survey data from Pew, in 2000 only 22% of Americans had ever shopped online, now 80% do, at least somewhat regularly” (Schrager). This large increase in online shopping comes largely from Amazon. “In 2018, Amazon took in $258.22 billion in sales, half of the online market, and 5% of US total retail sales” (Schrager). Amazon has successfully managed to stay on top with few competitors. The company has done this through its history and buyer return engagement. Since Amazon opened its site in 1995, it has the benefit of experience. The business had many years to test their aesthetic and technological variables on their website. Once they found what worked, they expanded, by using features such as Amazon Prime. This encouraged consumers to return to their site. Amazon was offering something you could not achieve in person easily or timely. The website had started allowing third party retailers which meant buyers can easily compare products in ways inaccessible to in person shopping. Then in 2014 Amazon began offering free two day shipping to Prime members (Yurieff). Now the lines between personal and online shopping were even more blurred as it cost nothing to get the item to your house and was there in a short amount of time. Soon consumers started to value the convenience, ease, and efficiency of e-commerce as the online shopping experience was as good, if not better, than that of in-person purchasing. Once other companies noticed this, they copied Amazon’s model. This is also known as the amazonization of e-commerce. While the aesthetic and technological variables of Amazon are innovative, the company did not revolutionize all of the shopping experience.

Overtime convenience has transformed buyer-seller relationships because modern day consumers do not copy the 19th century model. In the 19th century shopping experience, there were elaborate displays of products for the buyers to marvel at. Part of what they were purchasing was the wondrous presentation. In Zola’s A Ladies Paradise the exhibition of the parasols demonstrates this idea in detail, “Wide-open, rounded off like shields, they covered the whole hall, from the glazed roof to the varnished oak mouldings below… Madame Marty… could only exclaim, ‘It’s like fairyland!’” (Zola, 214-215). The consumers enjoy the ability to view the products at their leisure. From the design of the store to the creativity of these displays, it was all a tactic to encourage buying. Another example of this presents itself in the way multiple show windows were decorated. Eugène Atget’s photograph of Bon Marche 1926-1927 (Appendix 1) documented how the mannequins were not simply displaying the clothing, but telling a scene. The surrounding furniture, the positions of the figures, etc. were all meant to communicate a tone to the audience. In this particular image all the figures present themselves as of the bourgeois, thus communicating to the audience that to achieve this look, and to achieve this status, one needs to purchase these clothes. However, to truly appreciate this, buyers would need to have the desire to admire these show windows. For the shop owners to get this attention, they would have to dedicate themselves to crafting the eye-catching scene. After viewing this window, consumers wander the store to experience the leisure-ness that was prompted by the show window. There are various examples to showcase the 19th century shopping reality, but they all lead to the same point, which is that consumers mimicked the bourgeois by participating in the leisure experience these department stores set up. While today’s online shopping does not have buyers physically present, there are some similarities between the two.

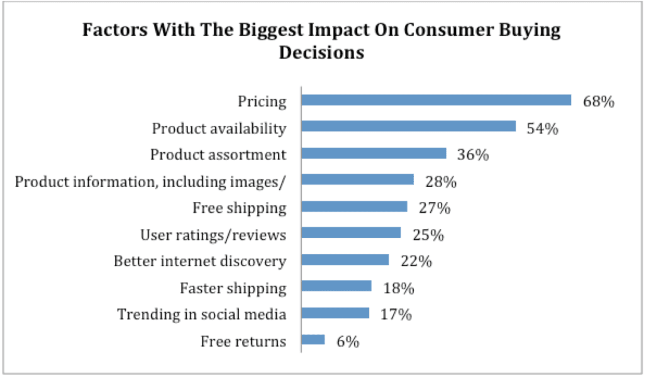

An important element to remember in the modern day shopping experience as opposed to that of the 19th century is that consumers did not stop valuing leisureness and bourgeois imitation just because convenience became more important. In the Riter graph (Appendix 2) price was the most important impact on consumer buying decision, but the other impacts demonstrate valuable information about the reality of online shopping. The product information, free shipping, user ratings, and so on are all important to the consumer. Buyers are able to spend as much time as they want searching for the perfect product. Instead of the department store influencing the presentation of these items, Amazon allows for product comparison, buyer experience, and more to influence the consumer. Amazon wants consumers to have the leisure of comparing products from multiple vendors to achieve the best product for the best price and quality. This varies from the 19th century department store that wanted the consumers to purchase their products and their products only, so the stores that had the best influence on the buyers had more sales. Amazon still wants its consumers to feel “valued”, so they offer Amazon Prime for premium customer service, free and fast shipping, and more. This service is similar to the bourgeois imitation since they want consumers to feel like they are of higher class with better service, but the yearly subscription does not have a ridiculous price that would discourage buyers. Amazon has carried similar elements of the 19th century shopping experience into their business model, but ultimately the modern day consumer desires quickness. Even if consumers were able to quickly walk into a department store and purchase their item, they would still have to allocate time and resources to get to and from the store. Online delivery eliminates this and their shopping experience comes down to a few clicks from the comfort of their home. Even though the buyer wants the convenience of online shopping, they still desire the leisure of product comparison and the bourgeois imitation of Amazon Prime.

The amazonization of e-commerce has impacted consumer desire due to the way technology has transformed society. Amazonization is a response to what consumers desire. Amazon made aesthetic and technological changes to their website to see how buyers would respond. Eventually Amazon created a website that fulfilled what the consumers wanted, thus leading to their extreme popularity. This popularity was only possible with the growth of technology. With the rise in technology came a trust in this new way of shopping. “78% of online shoppers don’t look at a product in a store before buying it online” (Saleh). Amazonization has cultivated a culture that turns to ecommerce and almost exclusively ecommerce. This feeds into the business idea Amazon has done so well, and has consumers come back for more quicker. “60% of online shoppers like to receive an incentive or promotion from a brand before shopping” (Saleh). Amazon will do whatever they can to have consumers return to buy again. This impacts consumer desire. Shoppers “like” the incentive because they feel valued by the company, again going back to the bourgeois imitation. However, consumers want their products quickly, hence Amazon Prime’s two day free shipping. So now the amazonization of e-commerce has become the amazonization of consumer desire. Amazon has successfully shifted the shopping experience to be online where amazonization has molded the consumer’s expectations. Shoppers want an experience the same, if not better, than buying in person. This only became possible with the convenience that came with the rise of technology. The amazonization of consumer desire has made it so that shoppers have a loyalty to e-commerce. For consumers to achieve this online shopping reality, they needed to support the elimination of labor time from their buyer-seller relationships.

Amazonization has made it so labor time has been removed from the knowledge of the consumer. On the Amazon website, there is no evidence of who exactly made and transported the product, which factory it came from, what shipping center it came from, where the raw materials for said product is from, and what impact on the environment this product has in its creation, shipment, and after-life. This information can be considered “friction” in the buyer-seller relationship (Tadepalli). If shoppers were able to access this information during the transaction, they may opt for another alternative. While price is considered to be the most important impact on consumer buying decisions (Riter), this graph does not take into account what would happen if websites had information about labor time. For some shoppers, price truly is the most important factor, but for others, knowledge of labor time may be more important if it were available to them. Karl Marx describes the dangers of eliminating labor time from the exchange value of a product:

It is precisely this finished form of the world of commodities – the money form – which conceals the social character of private labor and the social relations between the individual workers, by making those relations appear as relations between material objects, instead of revealing them plainly (Marx, 339).

What Marx illustrates here is that in capitalist societies is not expressed through labor time, rather, through relationships between products. Amazon highlights the relationship between products through its website functions (eg. easy to compare products, endless list of items, etc.), thus hiding labor time in favor of monetary value. For amazonization to be successful and for consumers to develop their current expectations, labor time had to be concealed so that there would be minimized “friction” in the buyer-seller relationships.

Amazonization has eliminated labor time to influence consumer desire towards monetary value. The benefits of focusing on monetary value as opposed to labor value not only minimize “friction”, but it also gives the seller the ability to demand for cheaper labor. If the market values lower prices for best quality, then to be able to achieve that lower price, sellers will need to find labor to be able to compete in the market. This creates ethical issues. A recent example has emerged concerning COVID-19, “An Amazon warehouse worker in New York has reportedly died from the coronavirus… The employee worked at the same Amazon warehouse that went on strike in late March over the company’s failure to protect employees from the pandemic” (Maytus). Amazon has forced employees to continue to work despite workers reporting improper protocol for health and safety protection. This has resulted in at least one death, with many ill, and a high probability of more infected. However, if you are to go on the Amazon website there is no evidence of them reporting on or insuring their consumers about this issue. In fact, due to the pandemic, online shopping has increased due to closure of in-person shopping. This is because the capitalist society, which helped develop amazonization through the rise of technology, has encouraged monetary over labor value. By not bringing attention to the elimination of labor time, amazonization elevates its technological advancements that put importance on monetary value. Now consumers are distracted by the company’s ability to upkeep their expectations from Amazon Prime, endless product lists, etc. even during a pandemic. Since consumers continue to purchase online, even in cases of necessity during a pandemic, then it supports the system that values monetary over labor time.

The elimination of labor time is harmful due to the exploitation of laborers. As previously mentioned, for sellers to be able to keep prices low they have to compromise somewhere. For amazonization to work and for consumers to have their expectations met, there lies a cost that the shoppers aren’t aware of at the time of purchase. Amazon highlights the monetary value to be able to hide the labor value, but this ends up exploiting workers. The current protests of COVID-19 Amazon warehouse workers are not anything new. “Two Amazon employees were fired for speaking out about the safety conditions in the company’s warehouses…. Four senators… wrote a letter to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos… calling for the company to give its warehouse workers benefits” (Matyus). These incidents have been rising with the success of the company. The more business they have, the harder their employees have to work to keep up with demand. Despite the workers coming forward, there continue to be incidents and lack of benefits, safety, and security for the employees. This is due to the importance capitalists society puts on monetary value. From the beginning of the department store in the 19th century there began that buyer-seller relationship in which the seller sold a fantasy about the product for the buyer. No longer was consumer culture about the product, but it was about that fantasy. The cost of having seemingly endless products in a store was not on the price tag, but rather it was the cost of labor time. The mass production was the danger Marx warned his readers about. The faster and more efficient companies became at producing and selling, the more they encouraged consumers to buy. This evolved into amazonization where e-commerce expedited the shopping experience even more. Consumers desire the convenience and efficiency Amazon crafted, but do not wish to face the consequences of labor time elimination. This fantasy keeps the demand up and despite the warehouse workers coming forward, consumers continue to participate in the expectations of capitalism because coming to the reality of labor time elimination means giving up the comforts of amazonization.

This paper explores the amazonization of consumer desire by analyzing 19th century consumer culture, today’s ecommerce and its impact from amazonization, and the dangers of labor time removal from buyer-seller relationships. While amazonization has influenced consumer desire by putting importance on monetary value as opposed to labor value, consumers continue to desire bourgeois imitation. Instead of the shopping experience being almost strictly a leisurely activity, ecommerce has made it so that the amount of time the consumer spends shopping depends on their desire. This facilitates the “come back for more quicker” experience Amazon has perfected. The danger in this is that the elimination of labor time brings ethical issues. Warehouse workers have protested the lack of benefits, safety, and security. Unfortunately, few changes have been made since consumers will continue to purchase from Amazon for convenience. Considering recent events, shoppers have limited options to even purchase products, so Amazon is taking advantage of this by forcing their employees to work and upkeeping consumer demands and expectations. The amazonization of consumer desire means that shoppers have become influenced by Amazon’s aesthetic and technological variables to continue to purchase from their store.

References

Atget, Eugène. Magasins du Bon Marché. 1926-1927. Albumen silver print. MOMA, New York City.

Marx, Karl. “The Fetishism of the Commodity and its Secret”. In Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1. Trans. Ben Fowkes. Harmondsworth: Penguin & New Left Review, 1976, pp. 163-177.

Matyus, Allison. “Amazon Warehouse Worker Dies of Coronavirus in NYC.” Digital Trends, Digital Trends, 6 May 2020, www.digitaltrends.com/news/amazon-warehouse-worker-dies-of-coronavirus-in-nyc/.

Riter, Trent. “Amazon Effects Consumer Expectations.” SPS Commerce, SPS Commerce, Inc, 6 Apr. 2020, www.spscommerce.com/blog/amazon-effect-consumer-expectations-spsa/.

Saleh, Khalid. “Online Consumer Shopping Habits and Behavior.” Invesp, Invesp, 11 Apr. 2018, www.invespcro.com/blog/online-consumer-shopping-habits-behavior/.

Schrager, Allison. “We Wouldn’t Have Ecommerce without Amazon.” Quartz, Quartz, 29 Oct. 2019, qz.com/1688548/amazons-control-of-e-commerce-has-changed-the-way-we-live/.

Tadepalli, Mahesh. “Amazonization – Speak the Language of Your Customers.” Manufacturing Marketing News Amazonization Speak the Language of Your Customers Comments, 6 June 2014, www.globaldirective.com/read-news/amazonization-speak-the-language-of-your-customers/.

Yurieff, Kaya. “Amazon Prime: A Historical Timeline.” CNNMoney, Cable News Network, 28 Apr. 2018, money.cnn.com/2018/04/28/technology/amazon-prime-timeline/index.html.

Zola, Émile. The Ladies’ Paradise: (Au Bonheur Des Dames). University of California Press, 1992.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Atget, Eugène. Magasins du Bon Marché. 1926-1927. Albumen silver print. MOMA, New York City.

Appendix 2

Riter, Trent. “Amazon Effects Consumer Expectations.” SPS Commerce, SPS Commerce, Inc, 6 Apr. 2020, www.spscommerce.com/blog/amazon-effect-consumer-expectations-spsa/.