By Capri Jones

The worldwide COVID-19 death toll just hit 1.6 million, amounting to a spectacular disaster. Since the virus’ discovery in December 2019, it has wiped out entire communities, and forced hunger, houselessness, and an inability to receive medical attention. The death and suffering that COVID has caused is spectacular. As Rob Nixon defines it in his book, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, spectacular violence is, “an event or action that is immediate in time, explosive and spectacular in space, and as erupting into instant sensational visibility.” While this may be the case for the pandemic itself, the events that cultivated the environment for death to become a new normal were not spectacular. Instead, they took place over time. It’s important to premise this article with the understanding that disasters are not natural. They are not nature’s best effort at revenge on the human species, or the result of a god punishing its people. Disasters are political, meaning that during events like the COVID-19 pandemic, life and death are predetermined. The conditions that led COVID-19 to develop, and in turn kill so many people, were crafted by the oppressive systems that we live under. It was by no accident that the virus became so deadly, instead, COVID-19 became weaponized by the war-like conditions baked into our capitalist system. For the purpose of this article, I will focus on the underlying disaster of the commodification of housing in the United States. But it is important to note that this is not the only underlying disastrous aspect of the pandemic that took place over time. The housing crisis is only one facet of the austerity-based society that has ripped away any access to safety—economic, medical, community—in an era of neoliberal globalization. It is with this understanding of death in 2020, that analyzing an abolitionist response to disaster is essential. I argue that abolition of the systems that cultivated the environment for premature death by COVID-19 to become a new normal is the only solution for survival in an epoch that is, and will continue to be, stricken by a myriad of crises.

A state-based system encourages its subjects to understand non-state based disaster response as a last resort. However, when the situation proves that the state has failed to keep people alive, we are often left with no other choice but to fend for ourselves. Despite the warnings of past outbreaks such as SARS and Ebola, the global neoliberal-capitalist system has persisted, leaving our society ill-prepared for survival against a global pandemic. Austerity-policy designed to fund tax cuts and subsidies to corporations and the rich, has left any state public health effort lacking in the funding necessary to protect its constituents. In addition, the pharmaceutical industry is shirking the very responsibility it is supposed to have: protection against sickness. Instead, Big Pharma has traded in its expectation to prevent sickness with a money hungry agenda, focused solely on designing cures and treatments. The more sickness, and thus the more treatments sold, the higher its shareholder values. It is this continuation of free-market capitalism that is continually creating vulnerabilities to public health crises.

Unfortunately, this vulnerability is not equally distributed and is particularly concentrated in regions that are experiencing more infection, death, and unemployment than their surrounding areas. A system striving for infinite growth has left vulnerable communities increasingly prone to the adverse effects of COVID-19. The lack of access to health care combined with no other option but to serve the elite—those that can work from home—through front-line worker service is the direct cause of disproportionate infection rates amongst communities of color.

In addition, out of sight is the slow violence being enacted upon these communities. Slow violence is that which is not obvious, and which happens over long periods of time over dispersed areas of space, a violence that is often delayed but ultimately just as ruthless (sometimes, even more so) as the violence we are used to, such as murder or sexual assault. The combination of neoliberalism, unequal access to medical care, a racist job market, and rent, has created a build-up of historical injustice in marginalized communities. Rob Nixon explains that slow violence is inflicted primarily on those that the system neglects to care for in the first place. It is those facing eviction or living on the streets, particularly Black and brown people, that are suffering from the slow violence of neoliberal exploitation.

In mid-March, the stock market crash had led to a net devaluation of nearly 30% in stock markets worldwide. Capitalism was bound to crash sooner rather than later. From Santiago to Beirut, protests were already mounting against global capitalism. Whether or not the dominant economic model can survive COVID-19 can only be learned in time. Capital accumulation is collapsing across the world: unemployment has skyrocketed, tourism is negligible, companies are going bankrupt, restaurants are closing, and festivals, sports games, and weddings are being cancelled. Local governments and institutions are cratering. Capitalism is dying.

In May, I had interviewed Matt, a community organizer in Queens, about the effects of COVID-19. Matt said that, “what seems to be the existential economic crisis is rent.” How will we pay for it if there is no paid work to go around? And if we decide that we cannot pay for it, how can we effectively rent strike? As the tides of crisis have changed and we’ve turned from mass death to economic cataclysm, non-state-based solutions to this crisis have become more important than ever.

The notion of property in our political environment is attached to an implicit threat of state violence. With property ownership or occupation, comes the landowner’s ability to use the state’s tools of enforcement to ensure that it maintains its capital accumulating abilities. On the ground, this situation plays out as renters, many of them no longer receiving income, are faced with monthly rent payments. The inability to pay rent allows for the owner of the accommodation to summon the state in order to evict the renter. In this situation, the police, acting as the state’s weapon of enforcement, are called, and violence ensues. A participant in the protest camp known as “Abolition Park,” which materialized over a fight to reduce the New York Police Department budget by one billion dollars, states:

If you try to go and have a house without money the police will come, sooner or later, and drag you into the street. Depending on the precise legal circumstances, they might also cage you, for hours (trespass) or years (breaking and entering). If there were no police there would be no one living on the street. People would simply go indoors to one of the tens of thousands of empty residences. If the police disappeared overnight, this would happen overnight. It would be over.

A state-based society is laden with disaster that has created the conditions responsible for the slow violence of COVID-19. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s temporary order to halt evictions is set to expire on December 31st, when, conveniently, COVID is likely to be at its worst state. The Aspen institute estimates that 30 to 40 million people in America may be at risk of homelessness in the next few months.

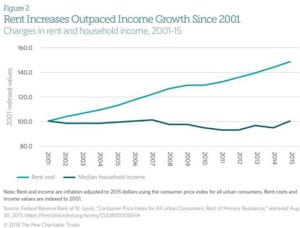

The commodification of housing is disproportionately harming Black and brown communities. Prior to the pandemic-influenced threat of eviction, 80% of those facing eviction were households of color. This phenomenon, the gap between white and colored communities facing the violence of houselessness, did not start with the pandemic. It is implicit in our economic model. In 2015, 46% of Black renter households were rent burdened as compared to 34% of white households. From 2001 to 2015, the demand for rental housing skyrocketed and increased the cost of rent. At the same time—shown in figure 2—the median household income stayed relatively the same, leading to the inability to keep up with monthly rent payments.

Figure 2 (PEW)

When the state chooses to actively disempower communities that are struggling, it becomes necessary to choose survival methods that fall outside of the federal government’s disaster relief agenda. It is in these moments, when we tear away the veil of superficial capitalist materiality, that systems of community-based survival prove their success. Underneath this veil, oftentimes we find an ungoverned commons, acting in ways that are altruistic and based in a culture of care. Mutual aid networks arise, solidarity is strengthened, and in turn, communities that were just facing the threat of death, are greeted with the hope of survival. This is not to say that we should pity marginalized communities about their inability to receive care from the government that is supposed to help them. Instead, in times of disaster when we see the state fail, we also see the power of non-state-based disaster response actually keeping people alive. In times of disaster, it becomes increasingly clear that people do not actually need to be governed, and can instead, govern and provide for themselves.

Shortly after George Floyd’s death on May 25th, 2020, a group of strangers, most of whom did not know each other, occupied City Hall Park in New York City. This was done partly out of necessity and partly because the intersection of crises—racial injustice, COVID-19, a heating climate, and capitalism—created an aperture in the film of superficial capitalist bullshit that caused us to become increasingly hopeful. A fluctuating group of, at times, thousands of people, who slept on the grass and sidewalk in front of the city’s government building, set up our own village. The demographics of the group are diverse, however an effort has been made to uplift the Black voices in the group, allowing for community decisions to be made by at first, mostly Black women, and now, a Black caucus which represents all of the Black people in the community. To be a white person (I, myself, being a part of this group), in the Abolition Park community means to be an accomplice in the struggle for Black liberation—listening to Black experience and using one’s whiteness only in ways that further aid in this liberation.

At the park, people were fed three meals a day, there was shelter from the rain, medical attention for those who had never had it, a library of Black radical literature to broaden our political understanding, clothing for when we ran out, and most importantly, a community of people that were ready to defend the community as the NYPD swung their batons and threatened to take away a sense of safety that many had experienced for the first time. Amongst the crowd of once-strangers turned comrades bonded through trauma, many were houseless. Many had been for years, many had recently been evicted, and because the encampment sprang up during the global pandemic, many were without work and facing eviction. However, at City Hall, there was shelter for those who needed it, and most importantly, it did not require a rent payment. The community that grew together over the month of June in the heat of a New York summer became known as Abolition Park.

Once the encampment was realistically no longer able to defend itself against the military force of the NYPD, it severed its ties to the territory of City Hall. Abolition Park proved that the physical location or occupation was actually the least important part of what we had built in a month. Post-City Hall, Abolition Park became even closer. Its organizational structure became more involved, more secure, and slowly, we trusted each other more. The Abolition Park food team fed, and still feeds, people dinner 6 nights a week. We house people that haven’t been able to secure shelter. We provide clothing for people. The community formed through Abolition Park gathers regularly to support one another, educate, point out our failures and successes, and plan and imagine what a future of Black liberation entails.

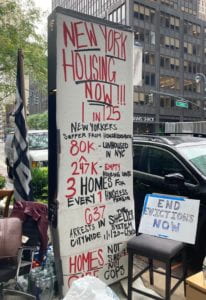

In addition to the culture of care that we’ve created, we have continued to organize housing actions. On October 2nd, Abolition Park abolitionists targeted the Sheraton at Times Square. We demanded that they open their doors, that 20 of their empty rooms be used to house some of the 80,000 people without homes on the streets of NYC. We demanded that empty hotel rooms should not sit vacant throughout the winter (and, frankly, at all times) while people slept on the street without shelter. A month later, after the Sheraton refused to comply, we set up in front of the Courtyard near Times Square, which had completely shut its doors due to COVID-19. Soon after, other hotels in midtown announced their closing dates, some of them with over one-thousand empty rooms. These rooms could save lives, but instead hotels are refusing to support the people despite their once elaborate claims that they cared for Black lives. An Abolition Park comrade said,

The pandemic has forced the hotel business to crumble. The amount of vacant hotels around the city versus the amount of houseless people during a pandemic is incredibly frustrating. The government has 400 billion dollars leftover from our first stimulus package but they want to save that money for the federal government. Give the extra 400 billion to the houseless and get these houseless people out the winter cold.

Simultaneously, living room pop-ups appeared in front of Governor Cuomo’s office and elsewhere around the city. We held press conferences, making it clear that houselessness in NYC is a disaster, and the tools to fix the problem are readily available to government officials. With over 247,000 empty housing units in the city, we demanded that the city cancel rent; extend the eviction moratorium; preserve safe, dignified, and affordable housing; stop the corporate takeover of the housing market; and finally, tax the rich.

Where New York City officials have largely failed to address the housing crisis, Philadelphia has proven otherwise. Throughout the summer, several homeless encampments including OccupyPHA and Camp JTD popped up in Philly showcasing the housing crisis, as well as demanding that the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) take action to provide shelter for those without. The two encampments moved across from PHA’s Headquarters as Camp Teddy, in an effort to pressure PHA to address the housing crisis. Eventually, the occupiers were successful. The residents who occupied Camp Teddy were given the opportunity to opt-in to social services to gain affordable housing facilitated by the non-profit organization, Project HOME and the city of Philadelphia. Additionally, agreements were made to create housing and job opportunities through a pilot initiative called “Working for Home Repair Training Program”—establishing a homeless relief program with the goal of allocating permanent housing opportunities for homeless families and utilizing long term vacant PHA properties and converting them into a Community Land Trust for permanent low income housing. Through a non-state based response to the Philly housing crisis, homeless residents of the encampments were able to keep each other safe during the summer and eventually gain access to permanent housing that would otherwise be sitting vacant, accumulating property value.

Applying an abolitionist response to disaster, particularly the disaster of the commodification of housing, means understanding housing is foundational for the liberation of Black lives. Looking at housing, particularly the housing of people of color, requires the analysis of heavily policed Black and brown neighborhoods and evacuation centers, the violence of evictions in these places, and the ever-present threat facing the houseless population. Another Abolition Park comrade states that,

Housing is a universal need, but the commodification of housing combined with the gentrification of urban space is leading to the mass displacement of people in their millions worldwide. Houselessness, evictions, lack of repairs and skyrocketing rent overwhelmingly affect Black, brown and poor people; robbing people of their housing, or of housing that actually meets their needs, is one way by which the state and capital rob people of what they need to survive. This is more intensely the case in the pandemic. An abolitionist approach to housing emphasizes that because safety is a relationship produced by care, not by policing, housing must be universally available and affordable. It also emphasizes that nobody should lose their access to clean, good shelter because of their actions. Everybody needs housing that supports their needs and sustains their lives, and universal access to housing will be a part of any abolitionist program worth fighting for.

In times of disaster, there are usually two paths that society can fall into. One of them is continued and strengthened authoritative control of society. The other is revolution. In times when the state is in flux, when it is flailing and unable to gain control of itself, there is an opportunity for revolution. It is in this moment that we should embrace what Shalanda Baker calls “anti-resilience.” Baker refers to “anti-resilience” as “resisting the obfuscation of systemic violence enacted upon communities of color and the poor in the name of energy. The act of engaging in a politics of anti-racism and anti-oppression that exposes the roots of structural inequality and vulnerability, and illuminated the path for system transformation.” Applying Baker’s transformative outlook on the energy system to the carceral, housing, and ultimately capitalist system, allows for the creation of new conceptions of surviving disasters that push past disparities attributed to social inequalities. An abolitionist response to disaster takes a transformative approach to the unjust systems in place, and when engaging with vulnerable communities the effort is not to make them resilient to disaster-laden systems, but to instead include these communities in the work of overthrowing and creating new systems while simultaneously using systems of mutual aid to meet each other’s needs. Along these lines, we can think about the intersecting crises of COVID-19 and housing as an opportunity for disaster-instigated-imaginaries. Stated by an Abolition Park participant,

In this moment where it has somehow become fashionable to say “abolish,” where the material meaning of “abolition” is in dispute, it’s necessary for people who actually want this to be over, who want the crisis to be fulfilled instead of sidestepped by ankle bracelets and UBI, to insist on this: if the cops are to go, for the cops to go, this entire hellworld must cease and be transformed by a movement that moves against and over all of it. The impossibility of just getting rid of the cops right now and just sauntering in to an non-commodified home is both really annoying and gives us opportunity, lines of attack, a fighting chance at such a revolutionary transformation, a shape to our struggles that inverts and negates the oppressive structure of this world.

Abolition Park is just that, an example of local revolution, organized to keep people alive where the state has neglected to do so. Abolition Park is a small scale response to disaster that serves as a model that can be scaled to an array of geographies, illuminating the prospect of a world where disaster is no longer inevitable.

Capri Jones (they/them) is a senior at Gallatin studying anarchist geographies and social movements.