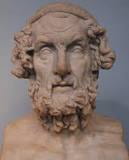

There is a passage in Casson’s chapter that struck me quite peculiarly and made me question some of the things that I, as a reader and as someone who has dabbled in writing himself, hold dearly about books. About half way through, Casson talks about how the Library of Alexandria was filled with a couple of different editions of Homer’s works, all of which were different from one and other on account of the fact that they had only been committed to paper centuries after the poet had lived and thus could hold no claim whatsoever of being an official, let alone an original, version of the text.

There is a passage in Casson’s chapter that struck me quite peculiarly and made me question some of the things that I, as a reader and as someone who has dabbled in writing himself, hold dearly about books. About half way through, Casson talks about how the Library of Alexandria was filled with a couple of different editions of Homer’s works, all of which were different from one and other on account of the fact that they had only been committed to paper centuries after the poet had lived and thus could hold no claim whatsoever of being an official, let alone an original, version of the text.

This treatment of the text and the seeming normalcy of it all suggests a fundamental difference in the way that stories were treated back then compared to now. Indeed, the modern history of literature, and of most forms of story-telling for that matter, is filled with stories about authors and artists who fought tooth and nail against editors, publishers and censors alike over every last aspect of their works, not wanting any interference whatsoever tampering with what they had envisioned. So the idea that an author—especially an author of such towering stature—would have such a detached relationship with the version of his work that has persisted through time is utterly puzzling.

I believe that my reaction to this has something to do with the sort of cult that has developed around the writer. I can’t comment on whether or not this is a recent thing, but I can say with certainty that now a days, there is a tendency to read the author along with the work that they produced. The idea that as readers, we’re reading words that have come directly from the pen of an author we idolize, or an author that has written “canonical” work or an author that has been labeled a genius has become something that is almost impossible to divorce from a given person’s reading choices. Conversely, I believe that there is also a certain egoism of the author that makes it important to them that people not only be compelled through reading, but that they’re compelled through their words.

Thus, the modern relationship between author and reader, one which is mediated as much through their book as through everyone else’s perception of their books, is one that isn’t necessarily in line with the way things were during the time of the Library of Alexandria. Of course, back then there really was no other choice as, even if someone wanted to read Homer’s original version of his works, there wasn’t any possibility of doing so. But nevertheless, the question remains whether we could learn a few things from this. Perhaps the test of a great story should only be whether it is capable of being captivating, not whether it is close to the original version of the text or what the author wanted the story to be. Then again, if an interest in an author and the authenticity of their text is something that supplements one’s appreciation of it, what would be the point in governing one’s interest?