Through the selection of books they curate, how have libraries historically portrayed “truth?” By viewing their catalogs holistically, how do different libraries portray different truths? Should libraries preserve all types, or specific kinds, of truth (e.g. propaganda)? What is the role of a librarian as a purveyor of truth? How have we, as information consumers and now curators, taken on that role ourselves? How has that role changed and adapted with the shifting permanence of text, as we moved from using mainly physical books to constantly changing databases (such as Wikipedia)? In a time when CNN (a reputable news outlet) publishes stories with the title: “ALLEGATION ABOUT SUSAN RICE UNMASKING IMPROPERLY IS “FALSE” ” (with the word “false” specifically put into quotations), what is the sociocultural and greater historical role of knowledge/truth collection?

Digitizing the Future

We currently live in a digital age. While digitization seems like the inevitable future of libraries—since it is extremely easy to access—it still has problems of its own. Digital information is harder to preserve, more expensive, and faces issues, such as “data rot” and an uneven distribution along socioeconomic lines. Furthermore, it seems that much of a material’s essence comes with its physicality, so when a book is digitized, it’s somehow changed. As a class, we’ve explored several futuristic libraries (including the Library from Dr. Who’s Silence in the Library) that still contain physical books instead of a fully digitized catalog. Moreover, many people have a great aversion towards reading eBooks, because they feel that it somehow takes away from the literature itself or their overall reading experience. How should libraries go about digitizing themselves (to fit our new digital age) in a way that they can both serve the public interest, but still retain the essence of the materials? Should digitization only be employed as a back-up to the real thing? Do you see fully digitized libraries in our future?

Imagine a Library

Visitors will travel up the Tower to the Glass Room overlooking a sea of clouds. Inside the Glass Room is a single, glass table floating above the ground. Any book that exists in the entire history of the universe (real or fictional) imagined by the visitor will immediately appear upon the table. Simultaneously, an exact duplicate of the imagined book will appear on the shelves of the Archives below the Tower. Thus, not only can visitors keep their imagined books, but a record of their visit will exist.

There is no boundary as to what book the visitor can think of. Any book—from the original manuscript of the Bible, to fictional books on the Defense Against the Dark Arts from Harry Potter, to the unpublished 1816 first draft of Frankenstein—will appear if wished upon. The size, color, font, and style of the book relies entirely on the imagination of the visitor, so no two books will ever be exactly the same. It is also impossible to try to think of (and summon) the same exact book as another person. Furthermore, there is no limit to the number of books one visitor can think of (as the glass box is bigger on the inside), and the Archives below are infinite.

Connoisseurs of Books

What struck me as I read Benjamin’s “Unpacking my Library” was the idea of ownership, and specifically the collector’s relationship to it. What does it mean to “own” a book? Does purchasing a book automatically mean ownership? Do the attributes and qualities that the book holds somehow pass onto its “owner”? What do our collection of books say about ourselves? What do they say about others’ perceptions of us?

In his essay, Benjamin claims that “the purchasing done by a book collector has very little in common with that done in a bookshop by a student getting a textbook, a man of the world buying a present or his lady, or a business intending to while away his next train journey” (62-63). In other words, Benjamin implies that book collectors’ acquisition of books has less to do with other people’s desires—such as a professor or a significant other—and more to do with a desire to “renew the old world” (61). But then, couldn’t you argue that in one way or another, we are all collectors of books (or at least objects that contain similar monetary value and knowledge that books do)? However, the difference between book collectors and the rest of the world lies in the intent. To Benjamin, a “real collector” would not only be someone who is able to discover the old and renew it with new life, but also someone who also has “a tactical instinct…and must be able to recognize whether a book is for him or not” (63-64).

Most people that make up the “higher” society of sought-after intellect seem to base their tactical instinct on reputation. Everyone makes judgments based on the books other people read. There’s a subtle, but enormous, difference between the judgments formed about a person whose bookshelf contains War and Peace, Finnegans Wake, and Les Misérables than someone who owns books like Twilight and Fifty Shades of Grey. On the other hand, true book collectors don’t care about the connotation or reputation of owning a book, but rather the specific relationship that comes from ownership itself and the life it gives to both the book and its owner.

Understanding the Aesthetic & Spiritual Experience

Tomas Augst begins “Faith in Reading” with a quote from William Poole about how libraries act as a stimulus to the librarians’ and readers’ religious emotions. This leads Augst to ask the question: “what was the sacral function of the public library?” (Augst 148). Augst summarizes the “aesthetic and spiritual experience created by public libraries” into four functions: popularization of ethical practices, organization/differentiation of attention, definition of community, and promotion of scripturalism (Augst 153). In the first essay, it would be interesting to analyze how libraries try to achieve these goals, specifically through visual materialization (e.g. statues and architecture). Large, public libraries—like the Boston Public Library and the NYPL—are built similarly to cathedrals in that they make people look up. What does looking up symbolize for Catholicism versus a secular faith in reading? Moreover, what is the difference between the symbol of looking up and the function of it? Often times, libraries also have several statues or busts of famous literary scholars. Even the reading rooms of Rome’s first public library were “decorated with statues of appropriate poets and orators” (Battles 47). What made these poets and orators appropriate? What did they symbolize? What function are these symbols meant to serve? By analyzing what these symbols are meant to inspire and what emotions they invoke, we can understand how they contribute to the aesthetic and spiritual experience created in public libraries.

Ancient Libraries: Burn and Conquer

One of the most intriguing issues we’ve discussed in class is how oppressive regimes often burn books and destroy libraries as a means of controlling certain groups of people (or, limit the public’s access to certain documents, also as a way to govern the masses). Similar to today, ancient libraries acted as fountains of knowledge and sources of culture, and were thus vital to the advancement of a society. However, while libraries (and the books they contain) were often used to promote the progression of culture, they were more often destroyed to delete certain cultures and revise unfavorable events from history.

The library of Alexandria not only “sought to compile and contain the entire corpus of Greek literature, as well as…[that] of many foreign languages,” but it also acted as an ancient think tank with a “community of scholars,” becoming a “prototype of the [modern] university” (Battles 30). In doing so, the rulers of Alexandria—or, Ptolemies—came to realize that “knowledge is a resource…a form of capital to be acquired and hoarded at the pleasure of the regime” (Battles 31). By buying and commandeering books to supply the library of Alexandria, the Ptolemies essentially created a “monopoly on knowledge—especially in medicine, engineering, and theology” (Battles 29). Consequently, the city of Alexandria rose in power, and its citizens prospered greatly. However, not every ruler who followed this philosophy employed it for improvement.

Qin emperor Shi Huangdi also came to discover that “a monopoly on intellectual resources was as important to rule as imperial control over the production of rice and silk” (Battles 37). As the self-proclaimed title of First August Emperor, Shi Huangdi sought to destroy any Chinese literature produced before his dynasty came to power, essentially marking himself as the beginning of history and subduing anyone who claimed otherwise.

Similarly, Spanish conquerors “tracked down and burned all the Aztec painted book they could find” (Battles 43). The conquerors committed to burning Aztec books, because they were not only valuable to Mexican priests and nobility, but they also posed a religious threat (Battles 43). However, what the Spanish rulers failed to realize was that the books they destroyed also contained much of Mexico’s culture, making it harder for them to Christianize the lands they seized. Thus, it makes sense that in the drawing entitled Priests burning Aztec books, we do not see actual books or scrolls going up in flames. Instead, we see key symbols of Aztec culture being torched, thus equating books to the art, music, and literature they contain.

Bobst Library: Current Periodicals & Newspapers

What makes a library a library?

OK, other than “having books,” what is one characteristic that is fundamental to the very essence of the library experience?

Hint: the smell!

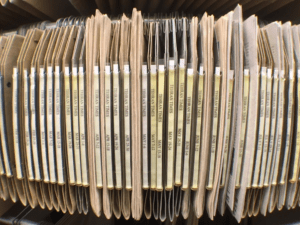

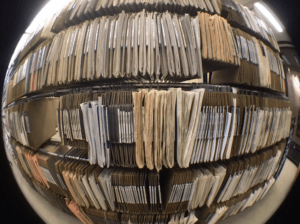

There’s something comforting and homey about the smell of ink and old paper, and the prime spot for avid sniffers is in the Current Periodicals & Newspapers room on the third floor of Bobst. Scholars who stake our their studies here are rewarded to a quietly muffled atmosphere, perfumed by old newspapers exuding a delicious muskiness. The most fragrant shelf has to be the last one, where rows upon rows of dusty brown folders stuffed with newspapers hang. Just by sitting next to these newspapers, I feel more in tune with current events and social studies as if the information is entering my brain through osmosis.

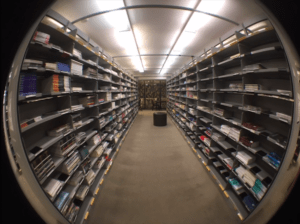

The overarching impression of the periodical and newspaper room seems to be an inviolability to the experience of the human race. Strolling through the shelves of articles, I begin to get a sense that, yes, there is a useful purpose to storing and preserving things like the Tehran Times newspapers and periodicals only about the opera or Lithic technologies. Unlike Seneca’s ideology that it “doesn’t’ matter how many books you have, but how good they are,” the periodical and newspaper room strives more towards that of a universal library of documented news and historical human perspectives of varying social importance. This approach of storing information seems to embody what a true library should strive to be: a place where someone can find any and all types of knowledge.