Pharmacy in 1920’s Harbin (dbs.bh.org.il)

Being a stateless person sucks. If you don’t believe me, ask the U.N.H.C.R., the United Nation’s Refugee Agency. In the East Asian context during the first half of the 20th century they were the Russian refugees fleeing from the Bolshevik Revolution (1917) or the subsequent Civil War (1918-1921) who experienced this condition and made it well-known for everybody in the region. The tens of thousands of White Russian émigrés who arrived to Chinese territories during the 1920s had to endure tremendous hardships. Not only that they were financially destitute and culturally alien in both the Chinese and other foreign “worlds”, but they also lacked consular representation. Between 1921-1924 the Soviet Union in a series of laws denaturalized those formerly Russian citizens who fled after the Tsarist regime’s collapse. The so-called Nansen Passports issued by the League of Nation were an attempt to give means of identification for them, but the ultimate solution was of course to obtain Chinese or another country’s citizenship. Masses of such impoverished Russians flooded the Shanghai French Concession that was complied to accommodate educated people with degrees and certificates earned in a different system.

Austro-Hungarian soldiers’s uniforms with Croatian description (Wikimedia Commons)

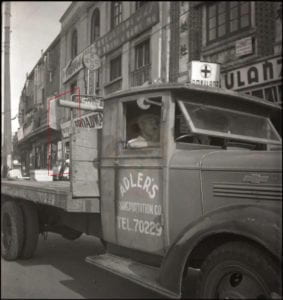

In 1937, 43 year-old Joseph Markovitch Franchich, Yugoslavian citizen was applying to the French municipal administration in Shanghai for permission to move his pharmacy store to the French Concession. His “Yugoslavian Pharmacy” previously operating on 1038 Broadway in the Hongkou (Hongkew 虹口) district had to be removed due to the hostilities following the 1937 Japanese attacks in the Wayside/Yangtzepoo area, and he was hoping to reopen it at 1248B Rue Lafayette. Born in 1894 Bjelovar, Croatia (Kingdom of Hungary) Franchich arrived in China as a former Austro-Hungarian refugee soldier. He earned his certificate (aptekarski pomochnik/аптекарский помочник) at the Harbin Pharmacy School in 1929 and started to work at a company named “Koffa”. In 1933 he moved to Shanghai and where following the necessary authorization, he opened his independent pharmacy.

The Seal of Shanghai French Concession (howlingpixel.com)

Franchich’s application was denied by the French authorities. Despite the efforts of the Jan Seba, the Czechoslovak Minister, in charge of the interest of Yugoslavian citizens in China, the municipality ruled against the permission. In his report and explanation of the decision, Dr. Y. Falud, director of the Public Hygiene and Assistance Services argued, that Franchich’s certificate cannot be accepted, as the regulation allows for only “pharmacist from Russian but not under the U.S.S.R.’s consular authority” to be permitted in the French Concession. Although Franchich attempted to re-apply with his Russian associate, M. Simakov’s name as the proprietor, but the request was repeatedly denied arguing that Simakov is just a cover and he didn’t even work there. It looks like, in this case not being a stateless Russian person was actually a disadvantage. So far, I haven’t found any indication whether Franchich was able to continue his career as a pharmacist nor any further information about him.

East Broadway, Shanghai in 1939- the red frames show the storefront where the ‘Yugoslavian Pharmacy’ operated (pastvu.com)

*Franchich’s Yugoslavian Pharmacy is listed at 1130 East Broadway in 1939–1941 business directories, practically next door to the original spot. His wife and daughter were living in the same building and it seems that the pharmacy continued to operate at the same spot as late as 1947. (Special thanks for this information and the photo to Katya Knyazeva, who’s writings you can find on “Mapping Old Shanghai”.)

Source: Shanghai Municipal Archives, U38 French Concession’s Conseil Municipal

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.