On October 22, I had the honor to present my research on some of the most interesting post-Habsburg Central European lives in Republican China. Those who tuned in the Royal Asiatic Society’s Shanghai Branch’s Zoom event were introduced to the fascinating political backdrop and personal stories of Jewish emigrants fleeing Hitler’s Third Reich to Shanghai and their locally settled benefactors: the Austrians, the Czechoslovaks, and the Hungarians.

ex-Austro-Hungarian POWs

Dr. Frederick Reiss, Austro-Hungarian Master of the Shanghai Freemason Lodge Lux Orientis

On May 6, 1934, friends and family assembled to bid a final farewell to Mr. Anton Felberbaum (b. in Vienna 1901), who died at his home on Jinkee Road under tragic circumstances. An Austrian by birth with a war record, the deceased was a member of the freemason lodge Lux Orientis of Shanghai. Master Dr. Frederick Reiss spoke on behalf of Felberbaum’s brothers, then prayers were offered.*

The banner of the Shanghai freemason lodge Lux Orientis; note the Temple of Heaven (天壇) and bagua (八卦) embroidery (L) and Frederick Reiss’ name (M)(Liveauctioneers.com) AND Dr. F. Reiss in 1933 (Israel’s Messenger via Brill)

Publication News: My article about Canadian Michael Kovrig’s grandfather, finder of the “forgotten Hungarians of Manchuria” was published

On Sunday, August 30, my feature article was published on the largest Canadian online news site. “Canadian Michael Kovrig’s grandfather, a Hungarian journalist, also went to China — and helped free his countrymen trapped a long way from home”

The story of Hungarian-Canadian journalist János Kovrig, grandfather of imprisoned ex-diplomat Michael Kovrig also appeared in print in Canada’s second highest-circulation daily newspaper the Toronto Star. Michael Kovrig is currently detained in China with alleged espionage. His imprisonment is widely believed to be retaliation for Canadian involvement in the US-China Huawei feud.

János Kovrig, just like his grandson, had a formative relationship with China, albeit a very different one. He launched his career right by the time when the Sino-Japanese conflicts got really hot in the 1930s. You can read more about his adventures across three continents, the “forgotten Hungarians of Manchuria” and his flight to Canada from his internment after his arrest by the Hungarian communist secret police.

Publication News: “The Flag of Paul Komor was Published in Hungarian

Today my article about the tragedy of Shanghai Hungarian Paul Komor was published. Written in Hungarian, it is introducing Komor, the savior of the Shanghai Jewish refugees, and the long time quasi-consul of the local Hungarian diaspora in Republican/Japanese occupied China (1915-1943).

Despite being the selfless benefactor of destitute Central Europeans for decades, Paul Komor was abandoned in his troubles by the Hungarian state during World War Two. Today, everyone, including the current Hungarian government’s culture diplomats and the Shanghai Hungarian Consulate General, is right to be proud of Komor. However, the less glorious parts of the story that were left to fade into oblivion now come to light.

Those reading in Hungarian, click on this link for the article on the online historical magazine Újkor.hu. Everyone else waiting for an English version, there might be coming up soon one in the form of an academic publication, so stay tuned! (In the meantime, perhaps a Google translation can give you the gist of the content.)

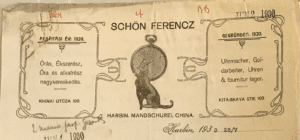

Settling on the shore of the Sungari. A Hungarian Jewish clockmaker in Sino-Russian Harbin

Ferenc Schön was a clockmaker and run a jewelry store on the Kitaiskaia Street (Китайская улица) – the pumping artery of Harbin’s commerce and business. Between the 1920s and 1940s he lived just next door to the New Synagogue on Jingwei jie (经纬街), where he visited the weekly service. His wife, Elisabeta and their daughter, Rahil were both native Harbiners/Harbintsi (Харбинцы)*, while Schön himself was born far away, the Russian Empire stretching in between his hometown and his residence for most of his life in Manchuria. Probably none of them imagined that one day they will move from the frigid Chinese Northeast to the sun-scorched land of Israel. In this post, I will sketch up the life of an ex-Austro-Hungarian prisoner of war of Hungarian nationality and of Jewish confession living in the Russo-Chinese town of Harbin, that for the most part of the period was occupied by Japanese forces. The aim here is to give an idea of the kind of people my research is dealing with.

Ferenc Schön’s letterhead advertising his Kitaiskaia store in Harbin, China, written in German and Hungarian languages (MNL)