Category: Reviews (page 4)

Ottessa Moshfegh’s Death in Her Hands: Works of Imagination in the World

Queens in Manhattan

“Rules for Visiting” and the Dangers of Sentimentalism

By Paul Oliver

By Paul Oliver

May Attaway, the fastidious narrator of Jessica Francis Kane’s new novel, “Rules for Visiting,” embarks on a journey to visit four old friends after her employer, a university in small-town Anneville, awards her a long leave from her job as a groundskeeper. Contrived inciting incident and possible underlying depression aside, May faces a rather common feeling of unrest: she is having a midlife crisis.

May visits her four old friends—Lindy, Vanessa, Neera, and Rose—to avoid the people closest to her, the people to whom she should dedicate her attention. These characters include her friend Leo (a budding love interest), her father, her coworker Sue, and her estranged brother. May prefers maudlin conversations with old friends to direct ones with the people who love her. She believes that “your oldest friends can offer a glimpse of who you were from a time before you had a sense of yourself and that’s what I’m after.” (Tony Soprano would tell May that“‘Remember when’ is the lowest form of conversation.”) The thing May lacks, though, despite her contemplative nature, is a precise sense of self. She feels lonely because she doesn’t know who she is—she never recovered from her mother’s death, and Kane wants the reader to sympathize with May’s condition as a single, middle-aged woman. Only in the final pages of the novel does May begin to foster the important relationships, the perennial ones (Leo, her dad). In this sense, the novel gestures towards a restorative sentiment, but too little too late.

Lindy’s daughter tells May, “My mom says you’re sad because you’re too old to have children.” Vanessa asks May why she’s still single. Indeed, May lives alone with only a cat for a companion (well, sort-of—she lives with her ailing father in her childhood home, the same home in which her mother suffered a tragic death). She’s inept with social media. Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram bewilder her. And she’s the type of person who has a name for her car. Bonnie.

The Frustrating Season Finale of “Euphoria”

By Eugenia Yang

HBO’s teen drama, “Euphoria,” has been in the spotlight since it premiered in the summer of 2019. The show has been called shocking and topical: it deals with drugs, sex, sexuality, and identity as its high school characters face problems like addiction, abuse, and teen pregnancy. The cast of characters includes: Rue, a recovering drug addict, who is home from rehab and back in high school; Nate, the spoiled star-quarterback; Jules, the young trans woman who is new in town; and Fez, a high school dropout turned drug dealer. The writers do a spectacular job of structuring each episode as an introduction to a character while simultaneously moving the plot forward without slowing down the pace. I find myself constantly on the edge of my couch, wondering when Nate will screw up the order of his dad’s porn discs, or when his dad, who hooks up with young men and trans women, will be exposed. We see the backstory and upbringing of each character and get a sense of why they are who they are. All the characters are far from perfect and they all make questionable life choices. The character who is the closest to making “morally correct” decisions is probably Fez and he’s a dealer whose assistant is a ten-year-old kid.

But that is exactly the beauty of “Euphoria.” And that’s why it resonates with young viewers. No, we aren’t perfect, and like Maddy, Nate’s on-and-off girlfriend, we tend to fall for the wrong people. No, we don’t always root for the most morally correct characters and are perhaps secretly on the team of drug addicts and drug dealers. We see pieces of ourselves in these characters’ flaws and understand that essentially, these imperfections are what make us human.

A Bunny Hop Into Nazi Germany: A Review of “Jojo Rabbit”

By Oliver Fosten

Taika Watiki’s new satire, “Jojo Rabbit,” can be summed up with the dialogue between the titular character Jojo, a ten-year-old living in Nazi Germany, and his mother, Rosie. Upon seeing a neat line of bodies hanging for crimes against the Fatherland, Jojo asks his mother, “What did they do?” as he looks away. His mother physically forces his gaze back upon the dead, somberly replying, “What they could.”

If You Are Ready for Language To Hurt, “Calling a Wolf a Wolf” is for You

By George Hajjar

I want poetry to fuck me up, and Kaveh Akbar knows how to do it.

Reading poetry is like going through a first breakup; you don’t always know what’s happening, but you do know you’re going to get hurt. Yes, I’m saying that all lovers of poetry are masochists. It’s true.

Phasers Set to Stunned: Perspective in “They Called Us Enemy”

By Hannah Bub

By Hannah Bub

George Takei, Star Trek star turned activist, has written a graphic memoir whose relevancy radiates off the page. “They Called Us Enemy” follows the internment of Takei’s Japanese family under Executive Order 9066, and brings the injustices of the American government to the forefront of public consciousness at a time when children are currently in cages at our borders.

Hard-Wired Traumas: A Retrospective of “Neuromancer”

By Thomas Lynch

Look, I’m not here to evangelize about some sci-fi book written in 1984 because it “predicted Trump” or something asinine like that. There’s a misguided tendency to review science-fiction purely based on its novelty when it is new and its prescience when it is old, and books like “Neuromancer,” which flirt with the literary, suffer as a result. Don’t worry, I’ll still be talking about “what it got right”—but it would be a disservice to “Neuromancer” to peg it as merely the novel which predicted what the globalized internet might look like. It’s a good novel, whether it invented the cyberpunk genre or not, and you should read it because it offers some valuable psychological insight into what the globalized internet might do to us as people.

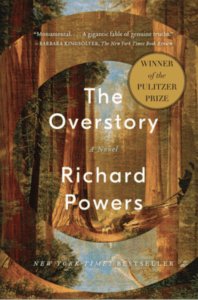

“The Overstory” is a Planetary Call-to-Arms

By Zach Tomci

By Zach Tomci

Imagine an organism billions of years old, constantly changing yet performing the same essential function throughout time. It is outside your window, lying under the cracks of sidewalks and producing the air you breathe in this moment. Through the lens of Richard Powers’s twelfth novel, 2019’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Overstory,” we are challenged to see the natural world in this mystical and reverent way. His story is immediately accessible and relevant, though it spans generations and takes place mostly in the 20th century. It is a story undeniably human; it is a story about us. More accurately, it is a story about the dual existence of humanity alongside the natural world, which Powers argues is just as complex and divine as the gift of human life.