Is it Heaven? Guidelines for Modern Love and Modern Life

By Zoe de Leon

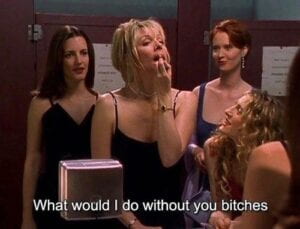

There is an iMessage group on my phone called The Three Blind Mice. The name refers not only to my trio of neighborhood girlfriends, but to our mutual love for the 90s hit series Sex and the City. In yet another episode of Carrie confiding with her three best girlfriends about relationship problems, she throws her hands up in the air and says, “I don’t need therapy, I have you guys!” to which Samantha, deadpan, replies, “We’re just as fucked up as you are. It’s like the blind leading the blind.”

In the span of six seasons, the women of Sex and the City displayed varying degrees of success in love and romance. The fictional failed relationships echo the very nonfiction reality of young people attempting to navigate interpersonal relationships amid a modern dating scene, where the rules were unwritten and the outcomes uncertain. Although familiar with the dating horror stories and questionable choices that haunted their circle, Carrie, Samantha, Miranda, and Charlotte still showed up for cocktails each episode to seek each other’s advice.

Women have and continue to turn to one another to discuss the realms of love, sex, and dating despite varying degrees and definitions of successful partnership. The very premise of Sex and the City revolved around writer Carrie as she guided NYC women through her popular sex and dating column. In the same vein, cult women’s interests books, with their tongue-in-cheek titles, have cemented themselves in literary iconography for their transgenerational cheekiness and wisdom.

With an eyebrow-raising title and OVER 1 MILLION COPIES SOLD! plastered on its cover, Why Men Love Bitches was the original clickbait survival guide. Sherry Argov’s 2002 self-help book includes chapters like “Act Like a Prize and You’ll Turn Him Into a Believer” and “How to Make the Most of Your Feminine and Sexual Powers.” Pages are packed with no-nonsense tips and sarcastic commentary to argue Argov’s main finding: a woman who is sure of herself and communicates her needs is a “dreamgirl,” and the too-nice, too-accommodating yes woman is a “doormat.” Encouraging its female readership to develop self-respect in order to inspire a new outlook on dating is the consensus of an entire genre of similarly no-BS self-help classics with vibrant on the nose titles that include, All the Rules: Time-Tested Secrets for Capturing the Heart of Mr. Right (1995), Women Who Love Too Much: When You Keep Wishing and Hoping He’ll Change (1985), Why Men Don’t Listen and Women Can’t Read Maps, and The Power of the Pussy.

This straight cis female-created and -oriented content has since morphed into short-form digital nuggets, chronically online in the same way its largely Gen-Z and millennial audience is, while favoring a more casual big sister approach. The number four podcast on Spotify is Call Her Daddy, a comedy and advice show where its millennial host Alex Cooper built a cult following around risque discussions of sex and college dating. The show is raunchy at best, with infamous episodes on oral sex that boast the neon green Spotify label of “Most Shared,” catapulting into a $60 million deal with the streaming platform.

Less NSFW creators have similarly tapped into the demand for women’s interests content featuring less vulgarity. TikTok is the platform of choice for the creator Tinx, an LA-based Stanford grad whose candid storytelling garnered a 1.5 million following. Tinx’s viral Box Theory video—where the creator emphasizes the importance of knowing that men categorize women according to their interest in dating, sleeping, or having nothing to do with them—is captioned with #datingtiktok #adviceforgirls and #rules. Its comment section is littered with virtual nods of agreement: “Men know what they want within 2 min!!”, “exactly what I needed to hear rn tbh”, “mom’s been telling me this. Couldn’t grasp it.”

Women’s interests content operates in a polished formula made up of key components: the creator tells the reader/viewer/listener what action—or inaction—to take on (“Don’t be the first to text after a first date”); shares the theoretical wisdom that informs this action (“Guys will make it obvious if they’re interested in you”); and provides empirical evidence to back up their claim (“The last guy I dated asked me out on another date as soon as we parted ways”). The end product is an extension of girl talk, classically looked down upon yet an established cultural imagery. It evolves from childhood slumber parties to Sex and the City-esque debriefings that finds women pooling together each other’s experiences, attempting to dissect and demystify all things love and romance in the hopes of learning from one another.

When I’m not logging into the digital void or bothering The Three Blind Mice for advice, I go to my mom. She made me read He’s Just Not That Into You by Greg Behrendt and Liz Tuccillo, a book she discovered in her late thirties and found so mind-altering that she saved the copy for her future daughter. The 2004 guide lists out acutely specific scenarios that indicate a guy is not interested in seriously pursuing a woman, framed into chapters with snappy titles like, “He’s not that into you if he’s … not asking you out.” Plastic-wrapped and yellow stained, the book may have been written nearly two decades ago, but its time-withstanding wisdom was passed down to me like sacred scripture, as though such required reading would lead me to some necessary enlightenment. He’s Just Not That Into You provided my mom with a new set of moral codes to live by and a much needed clarity of mind that, to me, seemed near biblical.

My mother’s faith in the ideology of He’s Just Not That Into You hand in hand with a dedication to its reliable guiding structures finds semblance to another unwavering project in her life. Coming from the Philippines, my mom is part of a generation of devout Catholic church-goers operating within the neat beliefs and rituals that only three hundred years of colonization could render, an imperishable legacy passed on to their own children, including myself. We were taught about our moral duties: attend Mass every Sunday, confess our sins regularly, capitalize every ‘h’ in ‘He’ and ‘His’ referring to God. We believe in Him and His commandments that range in tangibility, from “blessed are the clean of heart” to “thou shall not kill.” I personally don’t see how “blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the Earth” applies to Bezos-run, Arctic-killing hypercapitalism. I also know for sure that I don’t have the virtuous maturity to offer my other cheek when a person slaps me, as Jesus said was right to do. And although I wrestle with faith as an institution, I appreciate its lack of precarity.

Maybe it’s a tribal need for a higher force of guidance, but there is a peace of mind that comes with being provided terms to live by. Contemporary life is overcomplicated, knotted with circumstances and nuances––much of religious teaching is so lexically straightforward in comparison I can liken it to childlike naiveté. It’s probably why Christian education can begin so young. It’s easy for a kid to memorize that ‘doing good’ means, with no exceptions, loving their neighbor, caring for the earth, and saying a prayer before meals. Right versus wrong living, presented in its simplest terms designs a structured code of ethics. There is a motivation to assume what this code asks of us in the form of a neatly defined goal, one that we are conditioned to aspire towards: religion promises that these versions of paradise—Heaven, Nirvana, Enlightenment—are achievable.

Believing in a great ideal, that there is a ‘correct’ way to go about living, is a results-driven project shared by both religious practice and women’s interests content. The teachings that direct righteous Christian living are not unlike the supposedly no-fail techniques, step by step instructions, and hard set rules imparted by books, podcasts, and videos to find success in love. Their honesty reveals the human pursuit of empirically and theoretically backed guidelines, some sort of order that prompts better choices with tangible impact: successful relationships, wishes granted, a better life. Any proof that hope is not futile. It is this falsehood of guaranteed results that drives our search for both heaven and partnership.

There are shortcomings to both endeavors—the exploitations of institutionalized religion on one hand and the heteronormativity of women’s interests content on the other. The latter tends to be conceived by predominantly white women about exclusively heterosexual relationships. Pockets of it are informed by patriarchal systems. And on the most obvious front, it promotes the agenda that women are always talking about the opposite sex; it is the antithesis of the Bechdel Test.

Nonetheless, cheeky podcasts, #datingadvice videos, and the iconic books of the early aughts are still able to embody some form of individual agency. Like many readers, viewers, and listeners, I find great pleasure in how this champions women to influence the results of a power play that usually typecasts women as receivers to a man’s discretion, susceptible to his changing moods and subject to his assumed default to pursue. But I recall reading Why Men Love Bitches for the first time, and the flood of its platitudes washing over me. I was confronted with a magnitude of apparently universal truths about love, dating, and men that naturally begs the question, how am I supposed to memorize all this?

I began to pick at the cutthroat must dos and nevers women’s interests content tends to assert; the delicate treatment of every microscopic word, touch, text, or emoji as if there are end-all-be-alls provoked by choices I consider painstakingly minor. Is everything at stake if I reply to a text quicker than recommended? Is it decisively wrong to agree to drinks instead of dinner? Proactive participation on the part of women teeters fun and flirty while easily slipping into an exhaustive effort where the blame is pointed to her when things don’t work out: “She shouldn’t have said that,” “She didn’t…” “Why did she text him a heart?!”

There are some instructions set by women’s interest content that I consider nonnegotiable. I agree, for example, that a guy has the obligation to pay for a date he initiates. Yet there are still occasions I’ve had to turn to The Three Blind Mice with my own doubts: “should I be playing this game???” I’ve asked it too many times to recall. They’re probably worn out from being my personal consultants, but still manage to find the energy to remind me, “do what feels right for you.” You can’t find much of this encouragement in women’s interests content, though their affections are similar. Accounting for sincere individual ethos can only be understood by a handful of supportive women in my own real life: my mom, who is miles away East, and two girlfriends a few minutes walk from my apartment. Much like understanding that modern dating rules intend to cushion me from an undesirable outcome, knowing that there are people rooting for me is a security blanket I’m gripping onto tightly.

There’s an entire section of Christian education dedicated to explaining how God gave humans free will. The idea is that mankind has the option to choose their fate despite rules and commandments; it is free will that determines heaven or hell. How debilitating it is to know that choices I make may lead to—the horror!—consequences of my own doing. It feels like violence against self-preservation to set myself up for failure through my volition. It’s easier to follow orders and, if anything, find someone else to blame if things fall apart. But instructions are limited, and I will inevitably have to wade through the tumults of my early twenties without constant external reassurance.

Carving out an individual thought process without validation is a pursuit to uphold integrity while simultaneously defining what that even means. I’m still figuring out when guidelines set by modern dating culture feels authentic to me or if I am simply socialized to accept them as gospel. I’m still replying to a guy’s texts slower than he replies to me with no plans on diverging from this basic dating rule, not because I’ve been instructed to do so but because the game is fun. If I decide to change my ways, it’ll be on my own terms.

It is at once fruitless and instinctive to look for maps to direct modern living, such an uncharted, evolving, and personal territory subject to the best and the worst regardless of how carefully tread. No one is guaranteed heaven no matter how ‘good’ or ‘right’ they perform as a sentient being with even powers of love and destruction. No amount of advanced reading can prepare me for all the douchebags I’ll eventually deal with. I might as well embrace the full force of every emotion and experience along the way, and take responsibility for setting them into motion.