The Camera Was Always Running: Online Consciousness, Jonas Mekas, and Downtown Cultural Memory

by Sean Krupa

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running (until June 5, 2022 at The Jewish Museum)

Arrangement of Frames from the Films of Jonas Mekas, Sean Krupa, 2022

A friend called to let me know that he’s now familiar with every genre of pepper spray video. Another sends me video evidence of a nano-bot forklifting a sperm towards an egg – successfully curtailing insemination. On Twitter, someone replies to the “craziest video on the internet” (a zip-lining tween ramming into a sloth) with: “This is such weak tea…3 minutes ago I saw a video of a male horse trying to mount a female horse and the female horse kicks the male horse in the head and it dies instantly.” I continue scrolling, see an ad, a tweet about “vibe shifts,” and then watch as a Russian helicopter spins onto a Ukrainian highway, mushrooming in a cloud of blackened fragments, fog, and ruin.

If you’re online enough, you have probably seen more than one video of someone dying. It could have been an accident or an act of senseless harm. Often it’s a keyhole into wars, bombings, or beheadings: pixels delineating the boundaries of someone’s final memory. Responses to these videos are haunted by detachment and desensitization. The more extreme the simulacrum, the less real it seems, the more contained, as if the lives held within the frame had never existed on their own but rather began and ended when you pressed play.

There are more videos online than anyone could ever watch. Each day, one billion hours of content is consumed on youtube alone, roughly 32 years. More than 500 hours are uploaded in a single minute. For perspective, it would take 80 years to watch the amount of video uploaded to YouTube in only an hour. The excess of video available to watch is only eclipsed by the ubiquity of video currently being made. While you’re reading this, people are likely filming themselves eating, shooting, fucking, getting pepper-sprayed, and watching and reacting to other videos.

This feat in global surveillance feels like a reflexive call to arms. It’s as if, over the last century, an invisible banner has been raised in the name of recording and uploading everything physical, capturable by camera. In the wake of this mass mobilization towards video making and displaying, a new specter now plagues most people; if you are not recording it while it’s happening, how can you be sure it happened? Blame it on the news, Freudian-inspired advertising, uncurbed technological advancements, smartphones, social media, a rise in narcissism – whatever. Nonetheless, this online bank of video information holds one of humankind’s most enduring cultural records of the 20th and 21st centuries. The prevalence and instinct towards recording, uploading, and watching, thus, simulates a primarily unconscious and flailing cognitive process: memory.

(Cobwebs Spun Back & Forth In The Sky) – Nick Vyssotsky, 2021

(Cobwebs Spun Back & Forth In The Sky) – Nick Vyssotsky, 2021

The most memorable film I’ve seen recently is a collection of “liked videos.” The video maker explains: “Whenever a person uses social media, they are inevitably exposed to a broad spectrum of content, either posted by the accounts they follow or, as is becoming more common, shown to them by the platform’s algorithm, as it continuously trains itself on the content that better holds our attention. This content is usually offered up to the user without a great deal of context for what they are looking at. Ultimately, it is up to them to create the meaning behind what they see. ‘Cobwebs…’ is in this way a simulation of the experience of being online, filtered through media culled by one user, a subjective refraction of the digital spaces within which we live.”

Watching the film, Cobwebs Spun Back & Forth In The Sky, it’s hard to tell what is going on and what is real. It begins with a selfie seconds before a drone strike. What follows ranges: a tidal wave overturns an off-shore oil drill, molten lava leaks beneath a rainbow, and synchronized robots dance ceremoniously. There are also shocking and horrific scenes in this uncanny valley: an influencer runs from the Las Vegas shooting, fishermen chug beer cans found in the stomach of a fish, and police brutalize the homeless (also more pepper spray). Most of the clips are unsettling and overwhelming, with no inherent meaning or context besides the viewer’s impossibly limited interpretation. Algorithms programmed to pander videos of vitriol into echo-chambers harness similar illusions, as do the platforms that exhibit them. In this way, Cobwebs and online videos are puppeteered to show us a reflection of what we already think to be true.

The double-edged truth is that we are naturally drawn to decontextualize the uncanny and unexplainable. Ever since the advent of the motion picture, screenings of running horses and inbound trains defined the viewing experience as a dreamy simulation. In early cinema, light and motion transfigure a mere façade into something threateningly concrete. When the first cinema-goers left the theater, returning to their metaphysical whereabouts, they likely questioned the boundary between their reality and its reproduction.

The experience of watching a movie is not as reality-breaking as it once seemed. But as the rapid spread and consumption of online videos through social media and 24/7 news inundates our lived experience, the distinction between what’s on- and off-screen, what is chimerical, and what is real, becomes even harder to separate. We are now conscious, video after video, scroll after scroll, of unexplainable things outside our scope of imagination and explanation. This awareness, seemingly real but often devoid of any and all context, produces decade-defining anxiety: a sensation that what we see on-screen is happening all around us, all the time, and seemingly all at once.

Installation view: Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running, The Jewish Museum, New York, 2022. Courtesy the Jewish Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Perhaps no installation of recent memory captures this aspect of online awareness as the layout of Jonas Mekas’s exhibition: The Camera Was Always Running. Running at the Jewish Museum through June, the show is not designed by an algorithm as one might think at first. Condensed cuts of Mekas’ works (a highlight reel, if you will) are played on various screens that encircle sitting areas. While the films begin and end in predetermined patterns that spotlight standout scenes, viewers are engulfed in an ocean of sound and film. Like online videos, these scenes appear as decontextualized parts within the whole or posts on a feed.

Newly initiated and veteran viewers of Mekas’ work alike will find something thrilling in this experience, as the temporal and auditory disjunction of the films reveals a playful and prescient interconnectedness. The tall and looming screens, shaped like the alien sentinels from A 2001 Space Odyssey, also amplify this overwhelming experience. Viewers have the freedom to focus on a single screen or dizzy themselves trying to catch glimpses of the panoramic display. In this regard, the exhibition’s layout recalls the experience of watching online videos while scrolling down an algorithmic rabbit hole and would undoubtedly kill droves of Victorian children on sight.

The show also functions as a memorial in many ways, incorporating Mekas’ first feature (1962) through his last (2019), spanning several decades. Each screen stands like a monument or tombstone, interweaving Mekas’ films into the shape of a life lived through the lens of a camera. Mekas is famous for the syllogism: “I make home videos therefore I live. I live therefore I make home videos.” This vitality is made ever-present through the blindsiding presentation of The Camera was Always Running. As Zadie Smith once articulated watching the Christian Marclay’s time-synchronized The Clock: “You don’t feel that you are watching a film, you feel you’re existing alongside a film” (4). Surrounded by a lifetime’s worth of moments that Mekas felt driven to record, one can’t help but exist alongside him as he revitalizes a past of arresting beauty and intimacy. In this way, the installation does more than provide a new way of seeing through Mekas’ revolutionary camera. The Camera was Always Running acts to preserve his life’s work – to fossilize his rowdy spirit in the chromatic amber of home video.

As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000) Jonas Mekas

Mekas’ later films recall bodily impermanence. In Requiem (2019,) he shows us bouquets and meadows of flowers, all blooming asynchronously to Verdi’s own 1874 Requiem. Mekas died only hours after editing the work, leaving it unfinished and perhaps offering a final glimpse into his near-death consciousness. Televised interjections of all-consuming fires and floods, collaged with photos of Goya-esque violence, sour the springtime breeze. In Requiem, Mekas recognizes that growth and rebirth breed decay and death; here “April is the cruelest month” indeed. The French writer Michel De Montaigne, who acts as a spiritual forefather to Mekas in the way he attempted to study his evolving self in essay as Mekas attempts through video, writes “I have known the blade, the blossom, and the fruit, and I now know their withering.” Mekas confronts this “withering” in his last work, without being overcome by it. While his footage of flowers might be obscured by the wastelands of war and global suffering, he is not afraid to again see glimpses of beauty amid the terror.

One of Requiem‘s predecessors, A View From Greenpoint (2004), witnesses Mekas performing ritualistic banality with convivial cheer: he enjoys a beer with friends, sings on his recurring accordion, and jokes that he will marry his cat for a tax break. In these moments, he often says that he doesn’t know who he is anymore, conjuring tears. His existential crisis climaxes in a sung refrain: “All my friends don’t sing anymore.” The exhibited film ends with him leaving behind his SoHo apartment, the center stage of his earlier films, and the place where he and his family lived since 1974. A View From Greenpoint thus ventures into themes of dislocation and alienation that have long inspired and haunted Mekas’ work as an immigrant of war from Lithuania and a Downtown ex-patriot.

During its opening at Anthology Film Center, a similar sentiment for lost time and place permeated Vivienne Dick’s In Our Time. The film is nothing groundbreaking: a series of interviews on New York Life overlaid with flashbacks to the mythological 80s. This was a time and place when poetry, punk, new wave, pop art, and hip-hop were interwoven into a novel cultural fabric that would define the coming commercial and cultural spheres. The film’s central conflict then is how an artistic golden age was lost in the neoliberal wake of today’s New York. Dick brings attention to this repeatedly, juxtaposing her super-8 footage with digital video of over-saturated highrises and ceaseless construction.

As with many New York stories, Dick’s is primarily preoccupied with real estate. She provides a survivor’s testament to better days (imagine $80 rent for a one-bedroom in the East Village) and remembers when there were still neighborhoods Downtown that protested commercial chains out of principle for ensuring community. The characters in the film, mainly her friends and their children who are now struggling to pay to live in New York, develop the film’s secondary plot: a love letter to old friends. In Our Time often turns bittersweet, though, like in the scene when Nan Goldin laments about why she stopped taking photographs of people and now only shoots the sky: “All of my friends died.”

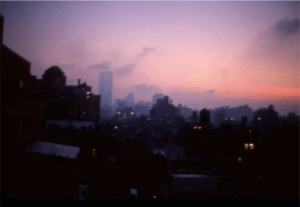

Apocalyptic Sky Over Manhattan, Nan Goldin, NYC 2001

At her 2021 exhibition, Memory Lost, Goldin showcased these fuzzy vignettes of sunsets and dawning skies alongside a new film centered on the opioid crisis. Her work from the 80s, such as The Ballads of Sexual Dependency and the Other Side, which pictured a Downtown New York full of drag queens and music, were also shown. During In Our Time’s Q&A, she admits that it was Vivienne Dick who inspired synching her works to a musical soundtrack, thereby contextualizing images with music – a typical venture in film since silent cinema and also in Mekas’s work.

The history of Downtown New York’s cultural impact is defined by interdisciplinary overlapping, as artists from every trade coincided in the same, relatively low-rent places. One of these artistic zones was the Film Maker’s Cinematheque which Mekas kickstarted in 1969. The theater focused on avant-garde films while also functioning as a focal point in New York’s avant-garde scene, even propelling Andy Warhol, one of Mekas’ students, into the cultural zeitgeist. The theater’s history makes clear that no one was as important to the exhibition and promotion of alternative film culture in Downtown New York as Mekas himself. Eventually, the theater moved locations and evolved into the Anthology film center, where Mekas spent his last years trying to build the largest film-focused library in the world.

Flash forward to 2022, when Goldin and Dick sit in the Anthology theater as an audience member asks: “How do you feel that everyone now is a photographer in one way or another?” Goldin’s response is typical for her laconic deadpan: “I always thought there were too many photographers…now it just so happens that I was right.”

In another sentiment, Mekas elaborates on the defining question for our image- and video-ridden-age at Lincoln Center in 2016:

Interviewer: “With all of these phone cameras, and everyone making videos everywhere all the time now, what do you feel needs to be explored in cinema?”

Mekas: “Why do you want to explore?… You don’t do it because there is a necessity for you to do?… Do you really seriously think you do what you do because you want to explore? Or not because you have this drive and necessity and if you don’t do it or you will go crazy…you have to do it…art does not have anything to do with exploration.”

Interviewer: “I suppose then it’s a silly question… I’ll just keep doing it.”

Mekas’ response essentially speaks to the role of an artist as video maker. Again, his answer is that in order to live, and as a result of being alive, one is instinctively drawn to making video. Mekas then identifies a key characteristic of video culture: recording, like memory, is conjured by unconscious reflexes. Mekas even admits that he often has no idea why he is filming what he films. In his defining venture into experimental filmmaking, Walden, (or Diaries Notes and Sketches), he confesses this with the on-screen proclamation: “I don’t know so I make films.” His work thus, in large part, is a project to contextualize an already decontextualized world: the world of outlying artists and immigrants (himself included).

The world of Walden is primarily one of Downtown New York at a history-defining moment, and Mekas stands as both witness and catalyst to this cultural growth spurt. Downtown New York notables, such as Yoko Ono, Allen Ginsberg, Andy Warhol, and the Velvet Underground, all overlap in the same spaces. The work is also notable for the way Mekas renewed avante-garde filmmaking methods, such as shooting with overexposed film, editing with inconsistent frame rates, and dramatizing sequences with stop motion. In his hands, these techniques evolve with integrated narration, text cards, and ambient noise that all serve as contextual compliments. In this way, Walden becomes Mekas’ first true “video diary” the form of video making that would become his staple. Mekas’ “video diaries” are entirely unique to the world of film, allowing him to capture an internal stream of consciousness while filming the external world going by. While Mekas might not know why he makes films, in Walden, he becomes content with celebrating how and what he sees, writing on screen: “They tell me, I should be always searching, but I am only celebrating what I see.”

Mekas is also quoted saying “home video is the folk poetry of the people.” This excerpt marked the entrance of MoMa’s 2021 exhibition, Private Lives, Public Spaces, which showcased the “largest body of moving-image work created in the 20th century.” This “body of work” consisted of home movies made by amateurs and avant-gardists alike, from suburban cookouts to a pitchfork-wielding Salvador Dali frolicking in his seaside garden. Private Lives, Public Spaces then sought to time-capsule a widespread consumer reaction to accessible video technology, a period defined by blurring lines between what is artistic and what is ordinary.

Mekas, who often said the main enemy of his films was the 20th century itself, didn’t exactly think everyone should make videos as his rallying call has been thought to signify. He once told a psychiatrist in 2016, who asked if he should begin making films, that he should stay a psychiatrist. Only if he was driven mad with the prospect of not making home movies, and only if he needed them to survive, would the psychiatrist get a pass. Still, many have framed Mekas’ populist rallying as a way of saying that the average video maker has the poetic potential to create “imperfect cinema.” A similar idea inspired García Espinosa, founder of the Cuban Revolutionary government’s film program, who remarked, “[imperfect cinema] is not only an act of social justice – the possibility for everyone to make films – but also a fact of extreme importance for artistic culture: the possibility of recovering… the true meaning of artistic activity.”

However, if the post-modern death of the artist has taught us one thing besides that not everyone can be a poet, it’s that there’s no true objective meaning of artistic activity. Today, it will not be the artist but rather the ordinary person who will unintentionally make videos that surpass any and all visual art in their cultural impact. For examples of this, look no further than pedestrians filming the Twin Towers collapsing or 17-year-old Darnella Frazier of Derek Chauvin killing George Floyd. In this light, our 21st-century tick to record everything has made online videos omnipotent and omnipresent, capable of reaching everyone and seismically shifting cultural foundations.

Mekas was prophetic in how he predicted this urge and its impact, channeling “imperfect cinema” with his unique form of proto-vlogging. By doing so, he not only pioneered the blueprint for Avante Garde filmmaking but also for recording and poetizing everyday life. However, one of the key differences between Mekas’ home movies and his 21st cultural successor is that today’s online video culture today is less concerned with honoring the process of seeing and has become blinded by a crusade to be seen. Seeing and being seen through online video in this way inspires mimicry and misrepresentation, often leading someone to develop online identities that drastically contrast their offline behavior. Moreover, Mekas, who is consoled with witnessing and not forming opinions, seems foreign to an online video culture that strives to convince viewers of a predetermined agenda – one they often already believe in.

As online videos continue to be exhibited in echo chambers through decontextualized forms, the experience of seeing them becomes arbitrary and unpredictable. While all video makers can harness its inherent poetic potential, whether intentional or not, the meaning is left to the viewer’s myopia. Accidental Cinema becomes the central output of today’s unconsciously driven video culture, one named for its random and endlessly interpretative ubiquity. We have all become video makers, with or without the poetry.

“In my films that Paradise is not yet lost, there are little bits of Paradise preserved.”

Jonas Mekas

Back on my phone, I see a satellite recording itself touching the sun. I see a bird of paradise flapping in a pond, and a giant squid washing ashore on the other side of the world. Climate calamity, road rage, and far-away wars all come into view. I am aware now that all of these things exist in the same breath, even if I have not witnessed them physically. This non-physical awareness speaks to something rare about being alive and online at this liminal moment in history. As cultural receivers and messengers, we are now permanently wedged between past and present, between time-traveling and time-keeping. Through online videos, we essentially simulate a collective memory, one that offers a skewed view into an everlasting hell, as well as brief glimpses of paradise.