Meat with a First and Last Name

By Sophia Anderson

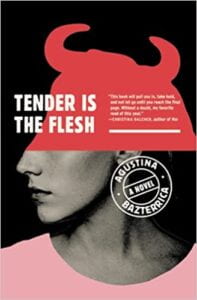

TENDER IS THE FLESH

By Agustina Bazterrica

Translated by Sarah Moses

“Horrifying,” “unnerving,” “brilliant”— these were the words that described Agustina Bazterrica’s cannibalist novel, Tender is the Flesh, on the reading recommendation side of TikTok. Although I usually have a hard time sticking with books during the school year, I was wrenched into this story right up to its unsettling end. The clinical language that paints the backsplash of dystopia seamlessly melds a clear social commentary with an exploration of the taboo of cannibalism.

The reader is immediately introduced to Marcos, a haunted man and the story’s protagonist. According to the government, an unidentified disease has made all animal meat poisonous. Humans (now referred to as “special meat”) have become the preferred form of protein. Marcos works as a trainer for employees at a slaughtering and processing facility for “special meat.” Between shifts, he finds himself in illegal possession of his own human, a woman he calls Jasmine. While she is not able to communicate verbally because those destined to be killed have their vocal cords removed, Marcos begins to care for her. At the same time, he copes with the grief of his dead child, absent wife, and his father’s mental deterioration. The only bright spot is Jasmine, who is learning how to be a person and, consequently, revealing what is left of Marcos’ sentimentality.

Entwined with his emotional decline, the novel explores the theme of capitalism: since animal meat is no longer viable, the government gives in to to corporate pressures to legalize cannibalism. What happens if one of the largest industries comes to a grinding halt? Laws are amended, regulations lifted, and the economy is forced to adapt. Marcos is himself a part of this effect. He works in the plant because his previous jobs included animal slaughter, meaning his skill set is limited and he is left with little to no other option. One of the most salient scenes depicts two potential employees touring the facility. One is a sadist, eager to begin the work of stunning and flaying, the other is visibly revolted by the inner workings. Sheer necessity forces him into the position, however nauseating it may be to him.

With Bazterrica’s dehumanizing language, the audience is compelled to feel that same repugnance as this employee. They are bombarded with images of women kept in cages for breeding, bodies spun at high speed on dehairing machines, panicked victims beaten and stunned for easier killing. All of it is designed to slowly desensitize the reader to the horrors presented to them. But how is it decided who is a person and who is an animal destined for consumption? Unsurprisingly, those who have been marginalized are the first to be dismembered and strung up in a freezer room. Marcos mentions disappearing immigrant populations and the desperation of the scavengers, who live on the outskirts of society. They are given nothing but the scraps of illegally obtained, rotten, or unregulated meat. A scene towards the end finds them overturning the facility’s new shipment of humans, a rebellion of pure hunger.

For all of its terrors, Tender is the Flesh is a grasp for humanity in an entirely mechanized world. As a lover and frequent reader of dystopian fiction, this book left me sick to my stomach in the best way possible. Bazterrica’s writing is the perfect combination of profound and disconcerting— with just the right twist at the end. After reading its takes on capitalism, death, and life, it is easy to see how a nation can slide beneath its own knife.

TENDER IS THE FLESH

By Agustina Bazterrica

Translated by Sarah Moses

Scribner. 211 pp. Paper, $16