Dreaming of a Homecoming: A Reflection on The Sellout

By Sophie Saddik

I have made many absurd statements recently, such as; likening a homecoming to opening a book or getting an oat milk latte from my favorite coffee shop around the corner. It is easier to associate home with things that will follow me wherever I live, to find comfort in objects or foods that will remain constant. It is the feeling of permanency I struggle with. Unable to feel comfortable if I sit in one place for too long, which is ironically something I yearn for. I imagine a future where I have an established home, a place that everybody knows is mine, a place where the people I love can easily frequent, and a place I know will always be there. However, whenever I am able to make this dream a reality, I freak out and find the easiest way to leave. I have lived in California, Israel, Pennsylvania, New York and even Spain for a brief moment and while each of them have provided me with a home, I still end up leaving.

I have made many absurd statements recently, such as; likening a homecoming to opening a book or getting an oat milk latte from my favorite coffee shop around the corner. It is easier to associate home with things that will follow me wherever I live, to find comfort in objects or foods that will remain constant. It is the feeling of permanency I struggle with. Unable to feel comfortable if I sit in one place for too long, which is ironically something I yearn for. I imagine a future where I have an established home, a place that everybody knows is mine, a place where the people I love can easily frequent, and a place I know will always be there. However, whenever I am able to make this dream a reality, I freak out and find the easiest way to leave. I have lived in California, Israel, Pennsylvania, New York and even Spain for a brief moment and while each of them have provided me with a home, I still end up leaving.

It makes me wonder: how far I would go to find my home, to find a place where, upon my return, will be worthy of the token phrase of ‘homecoming’. I didn’t know I had

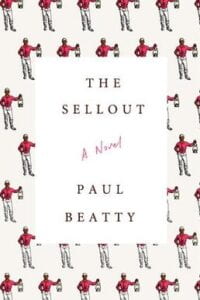

this problem until I randomly picked up The Sellout by Paul Beatty because it was my favorite shade of green. Here, among several other plot lines we follow the narrator, nicknamed Bonbon, as he reinstates slavery and resegregates the local high school in retalliation to the government erasing Dickens–his home town and proclaimed ghetto of Los Angeles. This was the result of the housing markets in surrounding towns seeing Dickens as a blemish on the surrounding properties values. Although this may be an extreme example, Bonbon finds that the most effective way to regain recognition for his home is to force an occasion where the government would have to recognize it, in his case being taken to court over his reinstitution of slavery, all the way to the Supreme Court. He feels lost without having a place to call his home; a feeling I share. I move, create a home without realizing it and then leave again, only acknowledging that I felt at home once it was too late. Then I romanticize going back, having a proper homecoming and feeling at peace.

My homecomings are always met with different people, different memories and with different expectations. When I go back to California, I expect comfort food, my parents and drives along 280. In Lehigh, my previous school in Pennsylvania, I expect a dingy frat basement, horrible food and some of my best friends. In Israel, I expect to be overwhelmed by extended family and really bitter coffee. And in New York, while I am still finding out who I am in this city, I know once I leave, it is the freedom and vibrancy that will dictate my time here, and maybe an oat milk latte from Everyman. It is in all these places that I have found different versions of myself, versions that would not be comfortable to find a homecoming in any place other than where I found them.

Thus, the chasm between my experience and that of the narrator is clear. Bonbon finds that he knows where his home is, that he will “die in the same bedroom [he] grew up in, looking up at the cracks in the stucco ceiling that’ve been there since ’68 quake” (68). He knows he would do anything for his home to be recognized with the respect he thinks it deserves and therefore does everything he can for his dream to be seen. I, on the other hand, have no idea where my home is. It seems contradictory that there can be more than one place that is home. How am I supposed to pick one place, even one version of myself, to feel at home in? Even though it may be a completely different journey than the one Bonbon experienced, it is through our shared innate desire to find a home that this book resonated so heavily with me.

I desire to have what he has; a place where he refuses to leave, a place where he knows he would only feel at home there. Maybe it is not the healthiest desire or even the safest, but the comfort of knowing that I have one place in the whole world where I can truly let my hair down is a comfort in itself. Sure, I am definitely missing the point of the book, such as focusing on the racial or class tensions explored, the flaws in America’s legal system, or even the relationships between the characters, but I think the beauty of reading is that people can take what they want out of what they read. Here, I was able to focus on what is apparently a really prevalent topic in my life, one I did not know I struggled with. I just want to be able to experience a true homecoming I guess, or perhaps get as close as I can.

A piece every college student must read.