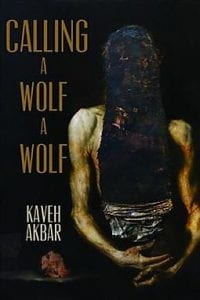

If You Are Ready for Language To Hurt, “Calling a Wolf a Wolf” is for You

By George Hajjar

I want poetry to fuck me up, and Kaveh Akbar knows how to do it.

Reading poetry is like going through a first breakup; you don’t always know what’s happening, but you do know you’re going to get hurt. Yes, I’m saying that all lovers of poetry are masochists. It’s true.

Akbar’s debut, “Calling a Wolf a Wolf,” is confessional and honest. He becomes the master of his own language, mixing Farsi, standard English, and his own kenning-English (“rosewater” “mothdust” etc.), to capture an utterly real life in manifold. He discovers it in a fleeting detail about losing a teddy bear named “Friend Bear” in New Jersey, in forgetting his first language, in drinking to excess, in drinking some more, in losing control, in naming loss, in feeling the weightlessness of an astronaut relying only on an umbilical cable for safety, and finally, in recovering. The speaker is always shockingly compelling, endearingly incomplete, and brutally magical.

Akbar makes it clear that he commands language differently than most. Often repurposing punctuation and playing with form, he is quick to teach you how to read him. “Soot,” the first poem in the collection, dances across the page “clumsy and gloomless, like new lovers,” tattooing painfully gorgeous images onto the reader.

Akbar beats his words and in doing so, beats his reader too. To that I say, give me your best shot. Take this final verse of “Yeki Bood Yeki Nabood” for instance:

I used to slow

dance with my mother in our living

room spiritless as any prince I felt

the bark of her spine softening I became

an agile brute she became a stuffed

ox I hear this happens

all over the world

Without punctuation, we feel each punch of the medial caesuras—the deep breaths before “spiritless,” every “I,” and every “she.” Akbar animates a simple dance with a mother through language; the caesura, coupled with heavily enjambed lines running into the next like the syncopated measure of a classical song creates the effect of rubato, as if a soloist plucks the mother and son into existence. Moments like these in the collection flaunt just what language can do.

Many of Akbar’s poems draw inspiration from nature and ritual, but just before we get hampered by the routine of this pain and waiting, he makes it strange. In “Wild Pear Tree,” he writes:

…our memories

have frosted over ages ago we guzzled

all the rosewater in the vase still we check for it

nightly I have forgotten even

the easy prayer I was supposed to use

in emergencies

The strangeness of the rosewater makes its routine hunt for a miracle compelling. Forgive me, I got carried away with quoting, but so much of the collection is about finding religion in the “peculiar.” It’s unfair to take any line away from a poem, or any poem from the collection because each word and theme sings so well together.

Akbar makes vulnerability intimate, giving the reader a gift that, like an asthmatic’s inhaler, they will need to carry with them at all times. If you’re ready to reread a poem called “Ways to Harm a Thing” for hours on end, pausing only to wince at how achingly honest it is that everyone is “too modern / to be caught / grieving,” then this book is for you.

George Hajjar recently graduated from NYU, where he studied both English literature and mathematics, neither of which he uses in his current job. He once wrote a fifty-page paper about the mouths of vampires.